Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

MECHANISMS OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING

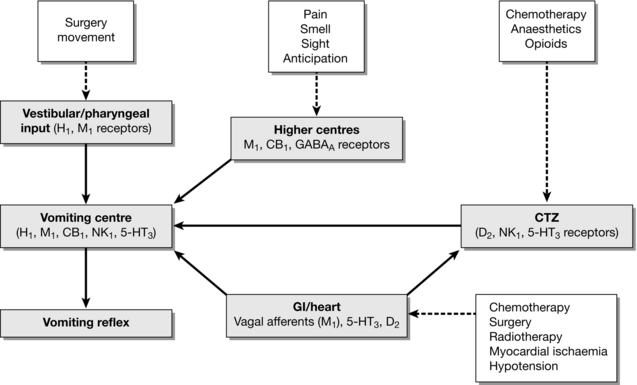

The vomiting reflex probably developed as an evolutionary protective mechanism against ingestion of harmful substances or toxins. However, vomiting also occurs in response to a wide range of pathological and environmental triggers including sight, smell, motion and gastrointestinal disturbances. Afferent signals mediated by the vagus, vestibular and higher cortical nerves are carried to discrete areas within the brainstem collectively known as the ‘vomiting centre’ (Fig. 42.1). Traditionally, the vomiting centre was thought to be a single anatomical entity but there is increasing evidence that it is made up of a disparate group of interconnected cells and nuclei located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). All information entering the vomiting centre is processed and co-ordinated (via autonomic and motor nerves) into a highly complex series of neuronal signals to initiate the three phases of the vomiting reflex.

Stimulation of the Vomiting Centre

Figure 42.1 outlines the various triggers and neural connections involved in the initiation of the vomiting reflex. The vomiting centre acts as the final processor for all sensory information received from central and peripheral receptors. Although the majority of afferent information from the periphery is relayed through the CTZ, other important causes of emesis are described below.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Some clinicians dismiss PONV as an inevitable consequence of surgery but from the patients perspective PONV is almost always associated with distress and dissatisfaction. Importantly, if nausea or vomiting persist there is a risk of rare, but potentially serious, perioperative morbidity. These complications are summarized in Table 42.1.

TABLE 42.1

Patient distress and dissatisfaction

Pulmonary aspiration

Postoperative pain

Wound dehiscence/haemorrhage

Eyes

Head and neck

Oesophageal

Abdominal

Dehydration, electrolyte disturbance and/or requirement for intravenous fluids

Delayed oral input

Drugs

Nutrition

Fluids

Delayed mobilization

Delayed discharge

IDENTIFYING PATIENTS AT RISK

Patient Factors

Although it is not possible to identify every patient at risk of PONV, a number of factors contribute to the incidence of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period. The main factors are shown in Table 42.2. Numerous studies report that smoking habits, female patients and those with a history of PONV or motion sickness are all strong independent predictors for PONV. Delayed gastric emptying, anxiety and obesity may increase the risk of PONV but the evidence for a statistically significant association is currently lacking. Children over the age of 3 years are also at high risk of developing PONV in comparison to adults. Vomiting, rather than nausea, is often used as an outcome measure in paediatric studies because of the difficulty in assessing and quantifying nausea in young children. Fortunately, the risk of PONV decreases as children reach adolescence.

TABLE 42.2

Factors Which Increase the Risk of PONV

Patient

Female

Non-smoker

History of PONV or motion sickness

Children (age > 3 years)

Anaesthetic

Volatile anaesthetics

Opioids

Nitrous oxide

Postoperative pain

Hypotension

Neostigmine > 2.5 mg

Surgical

Duration

Type

Gynaecological

Squint

ENT

Head and neck

Risk Stratification

One of the most widely adopted scoring systems developed by Apfel and colleagues uses four of the independent predictors described in Table 42.2 to determine the likelihood of experiencing PONV. These are:

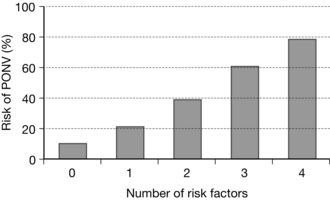

Each positive predictor is assigned a score of 1. Using this system, a score of 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 predicts the chance of developing PONV as approximately 10, 20, 40, 60 or 80%. (Fig. 42.2) Other scoring systems include the duration and type of anaesthesia but these have not been found to have any additional predictive value beyond that of Apfel’s simplified version.

MANAGEMENT

Treatment

Despite careful planning and risk reduction, some patients still experience troublesome PONV. If so, it is vital that all possible causes of PONV are ruled out to avoid missing important signs of serious underlying pathology. The commonest causes of PONV are highlighted in Table 42.3. Each patient should be thoroughly assessed to exclude other treatable causes. Only when these have been excluded is it appropriate to consider an antiemetic treatment strategy. If antiemetic prophylaxis has already been given, repeat dosing may be required depending on the pharmacokinetic profile of the initial prophylactic agent(s), while bearing in mind that a second dose may be ineffective and might simply increase the risk of an adverse drug effect.

TABLE 42.3

Hypotension

Hypoxaemia

Drugs

Opioids

Antibiotics

Intra-abdominal pathology

Psychological factors e.g. anticipation/anxiety

Early mobilization

Fluid intake

Nasogastric tube

Pain

PHARMACOLOGY

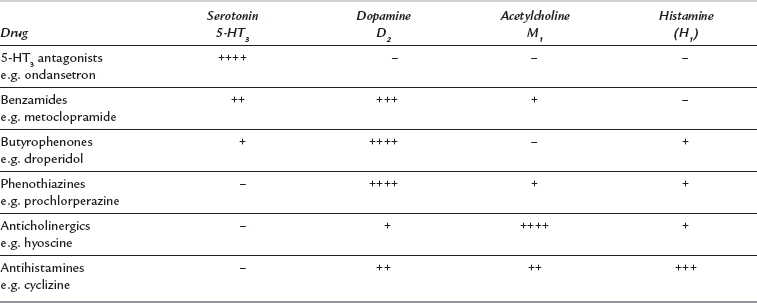

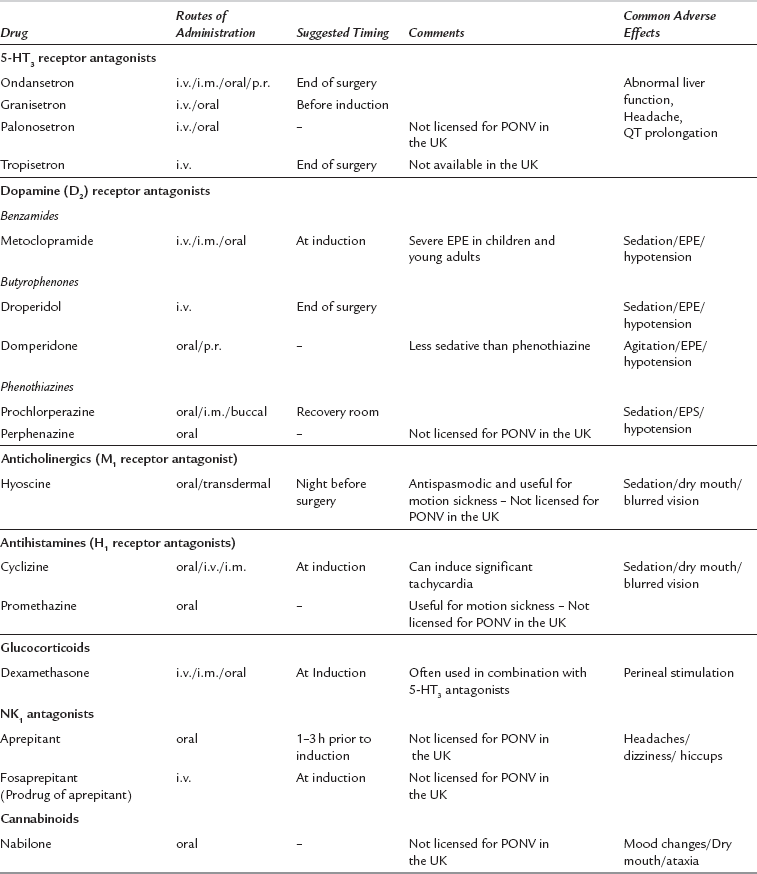

From an anaesthetist’s perspective, the numerous afferent and efferent components of the vomiting reflex lend themselves to pharmacological manipulation at multiple receptor sites within the peripheral and central nervous systems. Antagonism of one or more of the four key neurotransmitters involved in the vomiting reflex (dopamine, histamine, acetylcholine or 5-HT3) forms the basis of established treatment of PONV. Table 42.4 gives examples of the main classes of drug used worldwide for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. Not all are suitable or have been licensed for the treatment of PONV in the UK but are included in the table to indicate current or potential drug development strategies.

TABLE 42.4

Drugs Used in Management of PONV

EPE, extrapyramidal effects; i.v., intravenous; i.m., intramuscular; p.r., per rectum.

Dopamine D2 Receptor Antagonists

Peripheral and central dopaminergic D2 receptors are located within the gastrointestinal tract and the CTZ, respectively. D2 receptors mediate gastrointestinal activity and dopaminergic neurotransmission within the CTZ. The antiemetic efficacy of D2 receptor antagonists relates to a combination of increased gut motility and raising the emetogenic threshold within the CTZ. Butyrophenones, phenothiazines and benzamides act primarily as D2 receptor antagonists although most harbour cross-sensitivity with other receptor systems as shown in Table 42.5.

Phenothiazines

Phenothiazines were introduced originally to treat psychotic states including mania and schizophrenia. Subsequently, many were found to have useful antiemetic properties and are now used routinely during treatment of neoplastic disease. The main mechanism of action of the phenothiazines is via antagonism of the D2 receptor, but it is possible that some of their clinical effects are derived from blockade of other neurotransmitters involved in the vomiting reflex (Table 42.5). Prochlorperazine is used routinely in the treatment of PONV and labyrinthine disorders. It can be administered via intramuscular, oral or buccal routes. Side-effects include sedation, hypotension and extrapyramidal features.

Diemunsch, P., Joshi, G.P., Brichant, J.F. Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009;103:7–13.

Fero, K.E., Jalota, L., Hornuss, C., Apfel, C.C. Pharmacologic management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2011;12:2283–2296.

Gan, T.J., Meyer, T., Apfel, C.C., et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth. Analg. 2003;97:62–71.

Habib, A.S., Gan, T.J. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review. Can. J. Anaesth. 2004;51:326–341.

Watcha, M.F., White, P.F. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–184.