Problem 3 Postoperative hypotension

With the various possibilities in mind, you head towards the ward.

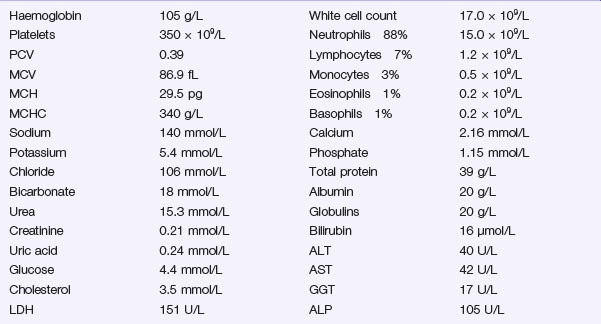

The following results become available:

Investigation 3.2 Arterial blood gas analysis on room air

| pO2 52 mmHg | pCO2 34 mmHg |

| pH 7.29 | Base excess −9.5 |

A portable chest X-ray is performed (Figure 3.1).

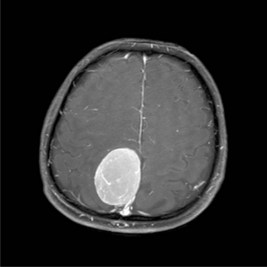

The chest effusions are further visualized with a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest and abdomen. One sequence is shown (Figure 3.2).

Answers

Cardiogenic shock occurs secondary to a primary pump failure.

There are several potential causes in this case:

You have these thoughts in mind as you head towards the ward.

A.2 Additional information may be available from several sources:

Look also for sources of infection such as:

A.4 The patient requires prompt resuscitation (A, B, C):

Most, units have ready access to crystalloid fluid such as Hartmann’s solution, or dextrose-saline. Both are isotonic and replace fluid and ions. They are, however, rapidly redistributed, particularly through leaky capillaries, into peripheral tissues. After high volume crystalloid transfusion, patients can become overloaded with fluid, but remain with low blood volume. This situation can ultimately hinder adequate tissue oxygen perfusion. A potential answer to this dilemma lies in the use of colloid fluids. Common colloids include Gelofusine and dextran. These fluids contain higher molecular weight molecules such as albumin or starch that slow redistribution and are designed to remain within the circulating blood volume. A Cochrane review in 2007 concluded that there was no evidence of improved outcome following resuscitation with colloid in patients with trauma, burns or postoperatively. The authors suggest that as crystalloid was cheaper and more easily available, it should continue to be the fluid of choice for resuscitation of the critically ill patient (Perel and Roberts 2007).

A.5 The results suggest the following:

A.6 The presence of fever, tachycardia, hypotension, dehydration and confusion indicate this patient most likely has severe sepsis. The development of pyrexia, tachycardia, tachypnoea and abnormal white cell count is defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome or SIRS. The criteria for a diagnosis of SIRS are listed in Box 3.1. When SIRS occurs in the presence of infection, this is termed sepsis.

Revision Points

Accurate assessment and early treatment of sepsis have been emphasized by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (Dellinger et al. 2008). Early, goal directed therapy is recommended in the form of ‘care bundles’. The immediate ‘Resuscitation’ care bundle is given within the first 6 hours, followed by the second ‘Management’ care bundle completed within 24 hours. It is recommended that broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is commenced within 1 hour of diagnosis of sepsis, with goal directed resuscitation within the first 6 hours of diagnosis. Initial fluid and oxygen resuscitation should aim at maintaining a central venous pressure of 8–12 mmHg, a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg, a urine output of 0.5 mL/kg/hour and a central venous oxygen saturation of over 70%. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) or dopamine can be used as vasopressors in septic shock as long as adequate fluid resuscitation is ensured (Table 3.1).

| Drug | Action | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) | Alpha agonist Vasopressor |

Septic shock, neurogenic shock |

| Dobutamine | Beta1 agonist Inotropic |

Cardiogenic shock, myocardial failure, without hypotension |

| Dopamine | Beta1 agonist Inotropic and chronotropic |

Cardiogenic shock ?Increase renal perfusion in low doses |

| Dopexamine | Beta2 agonist Inotropic |

Septic shock Increase splanchnic perfusion |

Numerous trials have looked at the use of steroids in severe sepsis. A recent trial failed to show any improvement in mortality following administration of hydrocortisone in septic shock. Although shock was seen to reverse more quickly in patients receiving steroids, they were more susceptible to further infections and sepsis (Sprung et al. 2008).

A key factor in the normal clotting mechanism is activated protein C. Levels of activated protein C are often low in severe sepsis, and its administration is known to have antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Two multicentre trials looking at the role of activated protein C in the management of severe sepsis have concluded that it may reduce overall mortality, but that it should not be used in patients with a low risk of death because of the associated risk of bleeding complications (Abraham et al. 2005, Bernard et al. 2001).

Shock is defined as inadequate tissue perfusion and its causes are:

Treatment of a patient with shock must include:

Those at high risk of sepsis and septic complications have been defined in Chapter 2 and include the elderly and malnourished, those with diabetes and any immunocompromised patients.

Issues to Consider

Abraham E., Laterre P.F., Garg R., et al. Drotrecogin alfa [activated] for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:1332-1341.

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 1992;20(6):864-874.

Bernard G.R., Vincent J.L., Laterre P.F., et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:699-709.

Dellinger R.P., Levy M.M., Carlet J.M., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign. International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock 2008. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36:296-327. [Published correction appears in Critical Care Medicine 2008;36:1394–1396.]

Perel, P., Roberts, I., 2007. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007 Oct 17 (4), CD000567. Review.

Sprung C.L., Annane D., Keh D., et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:111-124.