CHAPTER 24 Posterior sciatic block

Clinical anatomy

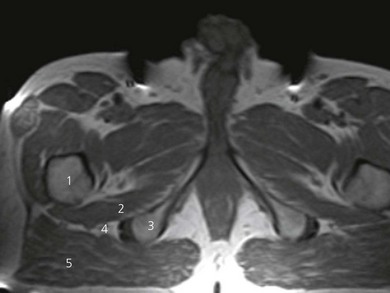

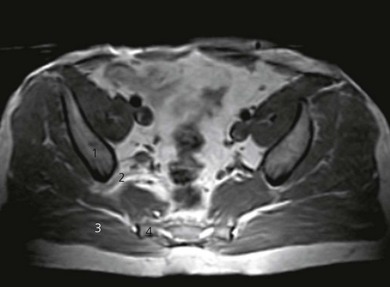

The sciatic nerve originates from the lumbar and sacral plexes and is the largest nerve in the body. The ventral rami of L4 and L5 join with those of S1, 2, and 3 to form the sciatic nerve. It is made up of two major nerves: the common peroneal and the tibial. The sciatic nerve arises on the pelvic surface of the piriformis muscle. It then passes out of the pelvis into the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle, and descends between the greater trochanter of the femur and the ischial tuberosity (Figs 24.1 and 24.2). Once it emerges from under cover of the gluteus maximus, it becomes superficial as it passes down the posterior thigh.

Surface anatomy

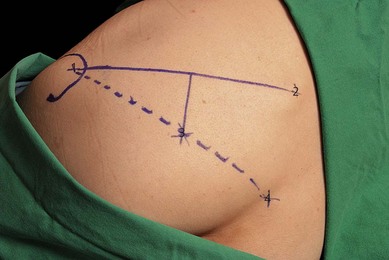

A consistent method of outlining the greater trochanter is needed because this is a large structure and variations can affect further marking. It is suggested that the outer perimeter of the greater trochanter is used for line drawings. A line is drawn between the posterior superior iliac spine and the greater trochanter (Fig. 24.3). This line is bisected and a perpendicular line is drawn passing downward from its midpoint. A further line is drawn from the sacral hiatus to the greater trochanter. The point at which this line intersects with the perpendicular line marks the point for needle insertion. The intersection is usually 5 cm along the perpendicular line.

Sonoanatomy

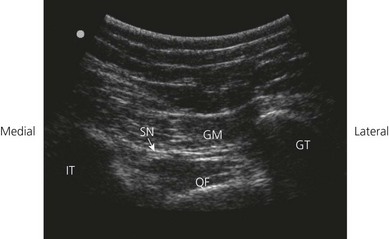

The patient is positioned laterally, with the side to be anesthetized uppermost and with the hip and knee flexed (Fig. 24.4). Perform a systematic anatomical survey from cephalad to caudad and from superficial to deep using a low-frequency, 5–2 MHz, curved array ultrasound transducer. The prominence of the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity are identified. These are seen as hyperechoic lines with shadowing beneath. On a sonogram, the ‘subgluteal space’ is seen as a hypoechoic area between the hyperechoic perimysium of the gluteus maximus and the quadratus femoris muscles (Fig. 24.5). It extends from the greater trochanter laterally to the ischial tuberosity medially. At this level, the sciatic nerve is seen as an oval hyperechoic nodule approximately 1.5–2 cm in diameter within the subgluteal space. It is often difficult to see the sciatic nerve due to tissue depth and reflections of muscles and fascial coverings. Follow the nerve by scanning proximally (cephalad) and distally (caudad) to follow the course of the nerve. It may be necessary to first identify the nerve in the posterior thigh region and then trace the nerve proximally, should visualization be difficult.

Technique

Landmark-based approach

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus (Sims) position (Fig. 24.6). A 100-mm insulated needle is used. The stimulating current is set at 0.75 mA, 2 Hz, and 0.1 ms. The needle is oriented 90° to all planes (Fig. 24.7) and advanced slowly until the appropriate muscle response is obtained: tibial nerve component produces plantar flexion and inversion of the foot, while common peroneal stimulation produces dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot. Hamstring contraction should not be accepted as a suitable response because it can be due to direct gluteal muscle stimulation.

Figure 24.7 Posterior landmark-based sciatic block technique. The needle is inserted in a 90° orientation to all planes.

The nerve is usually 7–9 cm deep to the skin. If bone is contacted, the needle is redirected medially or laterally. The initial stimulating current should be kept at 0.75 mA or less because direct stimulation of the gluteus maximus muscle (Fig. 24.2) with higher currents can mimic sciatic nerve stimulation. The needle may stimulate the inferior gluteal nerve (a branch from the sacral plexus). This results in rhythmic contractions of gluteus maximus; in this circumstance, the sciatic nerve is a few centimeters deeper and possibly 1 cm laterally. It is best to reattempt the block with needle insertion 1 cm lateral to the original site. The needle position is adjusted while reducing the current to 0.35 mA with maintenance of the muscle response.

Ultrasound-guided approach

Intravenous access, electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. Maximized comfort for the operator and patient is an important step in pre-procedure preparation. For the ultrasound-guided sub-gluteal sciatic block, the patient is placed in the prone or lateral position. The operator stands on the side to be blocked with the ultrasound screen on the opposite side (Fig. 24.9). Room lights may be turned down to enhance image viewing. The operating lights can be used to maintain some working lighting in the background.

A skin wheal of local anesthetic is raised at the medial aspect of the ultrasound transducer. The needle bevel should face the active face of the transducer to improve visibility of the needle tip. A free hand technique rather than the use of a needle guide is preferred. A 21-GA × 120-mm insulated regional block needle (Pajunk, Geisingen, Germany; or B.Braun, Bethlehem PA) is inserted within the plane of imaging to visualize the entire shaft and bevel along the path of the ultrasonic beam (Fig. 24.10). The needle is attached to sterile extension tubing, which is connected to a 20-mL syringe and flushed with local anesthetic solution to remove all air from the system. The operator can slide and tilt the transducer to maintain the needle tip within the plane of imaging as much as possible. The needle tip should be clearly identified within the plane of imaging before advancing the needle. The needle is advanced until it reaches the side of the target sciatic nerve (Fig 24.11).

Adverse effects

di Benedetto P, Bertini L, Casati A, et al. A new posterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: a prospective, randomized comparison with the classic posterior approach. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1040-1044.

Chan VW, Nova H, et al. Ultrasound examination and localization of the sciatic nerve: a volunteer sudy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(2):309-314.

Chantzi C, Alevizou A, Saranteas T, et al. Usefulness of the two to 5 MHz ultrasound probe in examination and block of the sciatic nerve in orthopedic trauma patients: a preliminary study. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:486-488.

Labat G. Regional anesthesia: techniques and clinical applications. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1924.

Oberndorfer U, Marhofer P, Bösenberg A, et al. Ultrasonographic guidance for sciatic and femoral nerve blocks in children. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98(6):797-801.

Saranteas T, Chantzi C, Paraskeuopoulos T, et al. Imaging in anesthesia: the role of 4 MHz to 7 MHz sector array ultrasound probe in the identification of the sciatic nerve at different anatomic locations. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:537-538.