CHAPTER 8 Posterior Ankle Arthroscopy for Conditions Causing Ankle Pain

Os Trigonum, Posterior Ankle Soft Tissue Impingement, Flexor Hallucis Longus Stenosis, Haglund’s Deformity, and Other Considerations

Posterior ankle arthroscopy is an increasingly used technique that allows the orthopedic surgeon to address a number of causes of posterior ankle pain.1–4 This minimally invasive technique has several advantages over traditional open surgical approaches to the posterior ankle, which can involve extensive dissection because of the depth of the ankle from the posterior skin. Concerns for wound healing problems in this high–tensile area of skin are minimized by the use of small arthroscopy portals, which often eliminates the need for postoperative immobilization and speeding recovery. One concern with using arthroscopic techniques in the posterior ankle region is the potential for neurovascular injuries.5 However, with application of good anatomic knowledge of the posterior ankle region and the use of proper technique, this approach has proved to be safe and effective.3–6 The magnification provided by the arthroscope allows the surgeon to work with greater precision and enhances the safety of the procedure. Several common causes of posterior ankle pain that are readily treated with posterior ankle arthroscopy are described in this chapter.

OS TRIGONUM

Os trigonum syndrome has been described in association with posterior ankle impingement in activities involving extreme plantar flexion, such as classical ballet and soccer. Also, a symptomatic os trigonum can be associated with tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon.7–10

Normal and Pathologic Anatomy

Symptomatic os trigonum syndrome can be caused by repetitive forced plantar flexion, as seen in ballet dancers and soccer players, although symptoms can arise in other athletes and in nonathletes after acute ankle injuries. The normal talus has a posteromedial and a posterolateral tubercle. The posterolateral tubercle provides attachment for the fibrous component of the beginning of the tunnel for the FHL tendon. An enlarged posterolateral tubercle is called a trigonal process, and one that is separated from the body of the talus is called an os trigonum. Sarrafian summarized four large series totaling 2142 talus specimens, and the incidence of os trigonum ranged from 2.2% to 7.7%.11 In some cases, an apparent os trigonum may represent nonunion of a fractured trigonal process after forced plantar flexion, but this has no bearing on clinical decision making or treatment.

History and Physical Examination

Athletes with posterior ankle pain due to an os trigonum have complaints similar to those of any patient with posterior ankle impingement; pain is worsened with plantar flexion. Posterior ankle pain can be vague by patient history, and the presence of FHL tenosynovitis can further diffuse the pain sensation. The physical examination finding of tenderness anterior to the Achilles tendon and retrocalcaneal bursa is strongly suggestive of posterior ankle impingement and can be elicited from both the posterolateral and the posteromedial sides of the ankle. This is particularly true when an unstable os trigonum is present. FHL tenosynovitis adds to the posteromedial tenderness in some cases. Extreme passive plantar flexion can exacerbate the pain, but this increase in pain is not specific for os trigonum, because it can also be found in cases of posterior soft tissue impingement.

Diagnostic Imaging

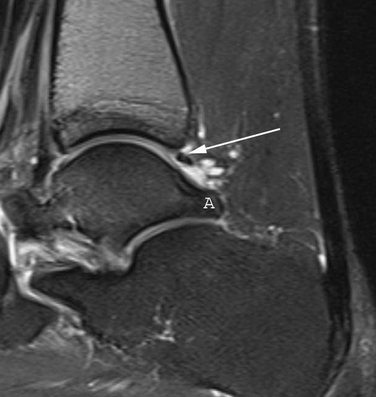

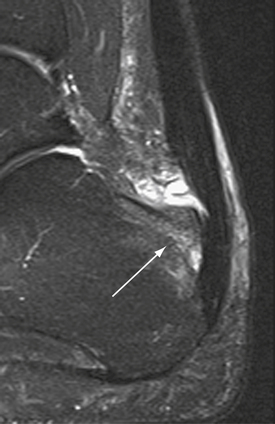

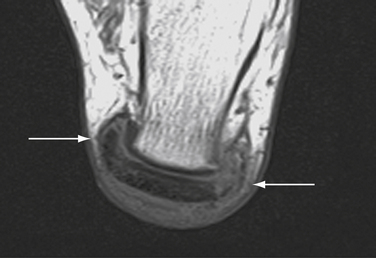

Radiographs are helpful for demonstrating the presence of an os trigonum or large trigonal process. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred test for assessing the pathoanatomy of the os trigonum, which is best demonstrated by bone marrow edema of the os trigonum and adjacent talus. MRI is also helpful in differentiating other causes of posterior ankle pain and impingement, such as FHL tenosynovitis, loose bodies, posterior soft tissue impingement, and occult osteochondral lesions (Fig. 8-1).12 Fluoroscopy can be used to guide injection of the os trigonum for diagnostic purposes.13 Ultrasound can also be used to assess the pathoanatomy of the posterior ankle.14

Treatment Options

Arthroscopic Technique

The ankle joint is marked anteriorly by placing a skin marker across the joint line of the dorsiflexed ankle. Two portals are made on either side of the Achilles tendon, 1 to 2 cm inferior to the anterior ankle joint line at approximately the level of the tip of the fibula (Fig. 8-2). This position allows adequate access to the ankle and subtalar joints. Alternatively, fluoroscopy can be used to confirm portal position. After the skin incisions are made, it is essential to use a fine, straight hemostat to spread tissues anterior to the Achilles tendon and make a puncture directly in the midline through the fascia separating the superficial and deep posterior compartments (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4). After this ventral fascia is penetrated, the hemostat is directed laterally and then advanced anteriorly in a posterolateral position behind the ankle. The hemostat can then be spread during removal to open the fascial opening. This is performed from both portals. It is important to maintain this method of placing instruments into the deep posterior compartment. Introducing instruments through this midline fascial opening from the superficial posterior compartment and initially directing instruments laterally protects the posteromedial neurovascular structures (Fig. 8-5).

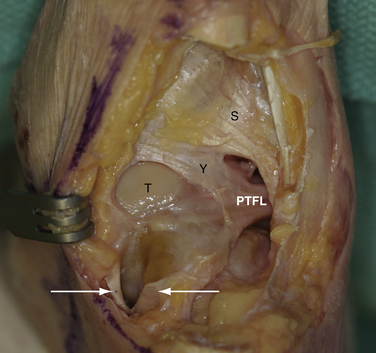

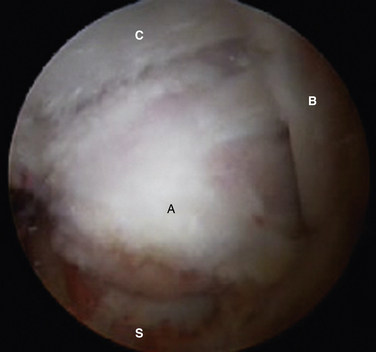

Initially, the arthroscope is placed through the medial portal and a soft tissue débrider through the lateral portal. Loose connective tissues behind the ankle joint are removed to demonstrate the superficial posterior tibiofibular ligament (PTFL) (Fig. 8-6). The ankle is dorsi and plantar flexed to identify the articular margin, and the os trigonum posterior to this point can then be cleared of lateral soft tissues. Some fibers of the posterior talofibular ligament are attached to the os trigonum, but the remainder of the PTFL attachment onto the talus should be preserved (Fig. 8-7). The subtalar joint is identified, and the clearing of soft tissues around the os trigonum continues, using the joint line of the ankle and subtalar joint as boundaries. Medially, the FHL tendon can be identified by moving the great toe into dorsiflexion. The FHL is used to mark the most medial boundary of the dissection (Fig. 8-8). The proximal attachment of the FHL tunnel is released from the os trigonum, which also serves to release the FHL, relieving any stenosis of the muscle or tendon simultaneously. At this point, the scope should be able to visualize the os trigonum well, and a freer elevator or similar blunt elevator can be used to probe the os and the fibrous junction between the os and the posterior talus (Fig. 8-9). In many cases, this junction can be loosened with a combination of the freer elevator and the shaver. Alternatively, a bipolar or unipolar cautery device may be used to strip the soft tissues, including the posterior talofibular ligament and the attachment of the FHL tendon sheath, from the os trigonum. After it is free, the os trigonum can be removed with a hemostat through either portal, although the posterolateral portal often works better (Fig. 8-10). It may be necessary to extend the portal enough to allow for the removal of a large os in some cases. Final inspection and débridement of the edges of the excision site can be performed. It is not uncommon for the calcaneal articular surface of the subtalar joint to be exposed posteriorly, because the os trigonum often has an articular surface that corresponds to the calcaneal side of the joint (Fig. 8-11).

PEARLS& PITFALLS

POSTERIOR ANKLE SOFT TISSUE IMPINGEMENT

“Posterior ankle impingement syndrome” was long used as a general phrase to describe posterior ankle pain that is worsened with plantar flexion of the ankle.15,16 Over time, a more anatomic approach to diagnosing the cause of posterior ankle pain has evolved, and posterior ankle soft tissue impingement is now recognized as a separate, although often associated, condition resulting from posterior bony impingement. Posterior ankle soft tissue impingement results from either a tear of the deep portion of the PTFL from the posterior rim of the tibial plafond or a tear of the posterior portion of the deep deltoid ligament (DDL).17–19

Normal and Pathologic Anatomy

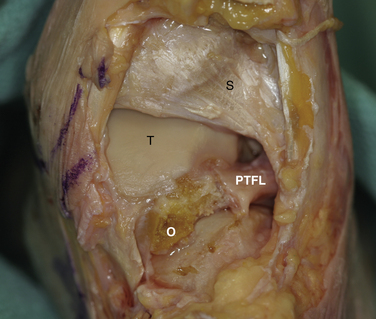

The ligaments of the posterior ankle have been well described and are pictured in Figure 8-6.20 The PTFL is composed of a deep and a superficial component. The superficial fibers are visible from the posterior view and fan out in a superior and medial direction from the fibular attachment to attach broadly on the tibia. The deep portion is a thick band that lies anterior to the superficial ligament and extends across the back of the ankle joint to the medial malleolus. It is not easily seen from the posterior view in an intact specimen. The deep band forms a labral rim of the posterior tibial plafond and increases the coverage of the posterior talus.

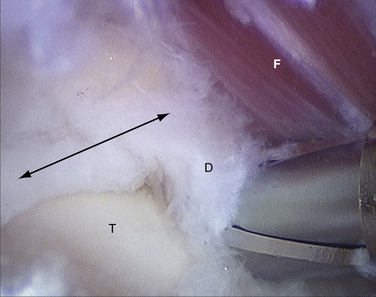

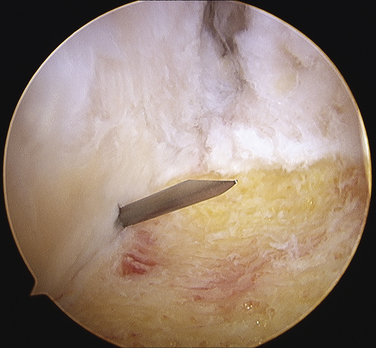

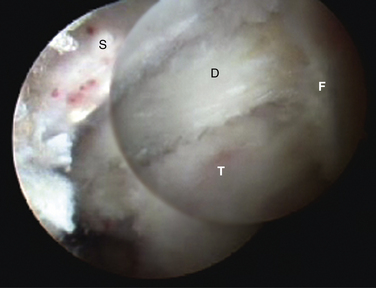

When the deep band is torn from the attachment on the tibial plafond, it becomes hypermobile and can displace into or out of the ankle joint, creating painful impingement symptoms. If the torn ligament is unstable, it usually lies in an inferior and more posterior position and can then be readily visualized from the posterior arthroscopic view (Fig. 8-12). If posterior impingement is suspected and the ligament is not visualized in this manner, a probe can be passed into the ankle joint and stability can be tested by pulling posteriorly on the ligament to determine whether it is displaced out of the joint. From the anterior arthroscopic view, posterior impingement is often not easily visualized with joint distention, but the ligament can be displaced into the ankle joint with posterior pressure, giving clear evidence of the instability and impingement.

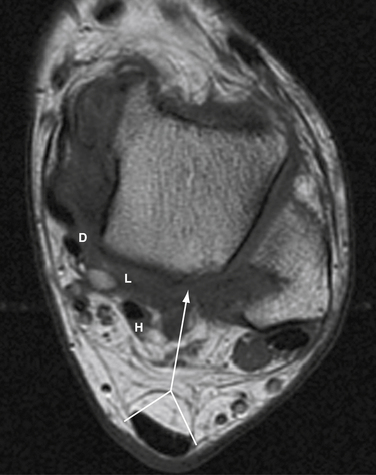

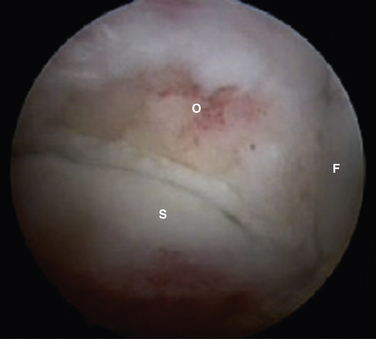

FIGURE 8-12 Posterior soft tissue impingement from torn deep posterior tibiofibular ligament (D). Figure 8-1 is a magnetic resonance image of the same patient. F, flexor hallucis longus tendon; S, superficial posterior tibiofibular ligament; T, talus.

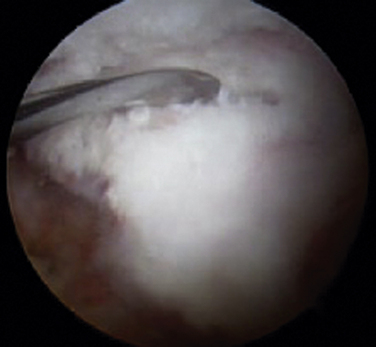

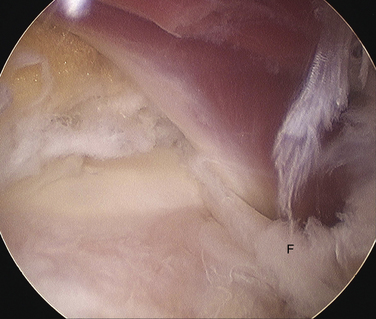

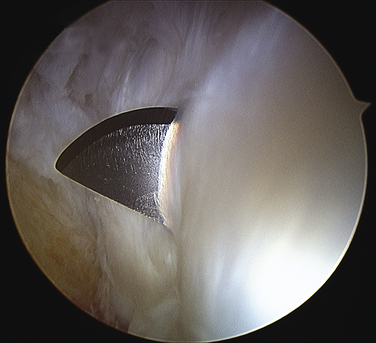

After débridement of the unstable deep PTFL is completed, the posterolateral talar dome is well visualized (Fig. 8-13). Posteromedial impingement due to a torn DDL occurs when torn fibers of the ligament remain flipped up into the posteromedial tibiotalar articulation, where the scar tissue mass creates impingement with ankle motion, particularly in plantar flexion. This configuration is not easily visualized on the initial posterior arthroscopic approach, because it lies anterior to the FHL tendon (Fig. 8-14). Often, there is surrounding scar tissue in the area, which can include the PTFL, and this lesion may be visualized only after initial débridement in this area.

Diagnostic Imaging

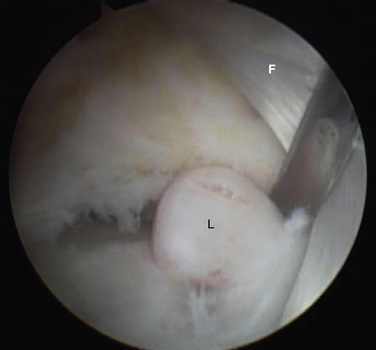

A lateral radiograph may show an os trigonum or a large trigonal process, which can cause posterior impingement, but the presence of one of these findings does not rule out the possibility of associated soft tissue impingement. MRI has become a very helpful tool in assessing the anatomy of the posterior soft tissues of the ankle.18,21–24 The finding of detachment of the deep PTFL from the plafond on the sagittal MRI views is diagnostic for injury to the ligament and can suggest the degree of displacement possible (see Fig. 8-1). The normal DDL is well visualized on MRI, and injury to it can be clearly detected.18 A mass of soft tissue resulting from a ligament tear that is displaced can be visualized. Magnetic resonance arthrography may help in some cases to better delineate the anatomy of an impingement lesion and to assess for other pathologies such as loose bodies (Fig. 8-15). Ultrasound has also been described as a useful method of studying the posteromedial ankle and evaluating for impingement. Although it is a growing area of diagnostic radiology, this powerful diagnostic tool remains a specialized skill that requires expert knowledge of foot and ankle anatomy and pathology.14,18

Treatment Options

Arthroscopic Technique

Positioning, portal placement, tourniquet placement, and anesthesia are performed in standard fashion as for a prone ankle arthroscopy. On the initial inspection of the posterolateral ankle, the talus is often obscured by the deep portion of the torn PTFL. When the ligament ruptures from its attachment on the rim of the posterior tibial plafond, it often falls into a more inferior position and lies below the superficial portion of the ligament (see Fig. 8-12). Alternatively, the ligament may be displaced into the ankle joint and can be mobilized with the use of an arthroscopic probe to pull it posteriorly, revealing the instability. The residual attachment to the posterior tibial plafond can be variable, and in some cases the ligament may be attached only at the origin and insertion points. A combination of arthroscopic débriders and cutters is effective to extract the unstable ligament, which usually entails removing the majority of it. Débridement of the tibial slip (intermalleolar ligament) may be necessary in some cases as a part of this débridement (see Figs. 8-6 and 8-7).

Excision of a posteromedial soft tissue impingement lesion is performed by gaining access to the area just anterior to the FHL tendon. If concomitant débridement of the PTFL is required, the medial portion must be débrided simultaneously. An arthroscopic probe can be used to retract the FHL tendon, allowing inspection of the posterior aspect of the medial gutter of the ankle. Normally, the posterior fibers of the DDL can be visualized in their anatomic location and the gutter is clearly visible. If the gutter is obscured by a displaced portion of a torn DDL, a small débrider can be advanced lateral and anterior to the FHL tendon (see Fig. 8-14). I prefer a small end-cutting shaver (2.9 to 3.5 mm) to débride this lesion, because the shaver will be pointing directly at the lesion. One great advantage of the posterior arthroscopic approach for this lesion is that, under the magnification of the arthroscope, a very precise débridement can be performed quite safely, without the morbidity of open dissection in this location. Figure 8-15 shows a small loose body anterior to the FHL tendon that was contributing to posteromedial impingement in this the patient, a football lineman, along with concomitant posterior soft tissue impingement and painful os trigonum (see Figs. 8-8 and 8-12).

PEARLS& PITFALLS

FLEXOR HALLUCIS LONGUS STENOSIS

FHL stenosis has been described in relationship to os trigonum impingement.8,10,24–26 However, understanding of the spectrum of FHL pathology is growing, and recent reports have even suggested a relationship to the genesis of hallux rigidus.27,28

Normal and Pathologic Anatomy

The FHL tendon enters a fibro-osseous tunnel that begins behind the talus in a groove formed by the posterolateral and posteromedial tubercles of the talus (see Fig. 8-6).29 Many symptomatic patients seem to have a primary stenosis of the entrance to the tunnel, caused by a low-lying muscle belly of the flexor hallucis, which creates a tethering of the muscle and chronic irritation of the muscle and surrounding tenosynovium (Fig. 8-16).8,10,24,26,28 This can be seen in some cases to result in atrophy of the chronically compressed distal end of the muscle.14 The fact that FHL stenosis and os trigonum impingement occur more frequently in ballet dancers and soccer players may have as much to do with the dynamic function of the FHL for the specialized demands of these activities as with the frequent plantar flexion that they require.30

History and Physical Examination

The history of FHL stenosis is often closely related to one of the posterior ankle pathologies; however, when found in isolation, it can have a more diffuse presentation. As with other tendinopathies, the symptoms of FHL stenosis can radiate up and down from the location of mechanical irritation. Patients may present with medial rather than posterior ankle pain, and the pain may radiate up the medial calf or behind the ankle or be manifested in the first metatarsophalangeal joint.8,24,26,28 Physical examination often reveals focal tenderness over the entrance to the FHL tunnel. This tenderness is increased with passive dorsiflexion of the ankle and hallux, which puts the tendon on stretch and delivers the muscle belly more distally, recreating the stenosis. This area can be specifically palpated by placing direct pressure from posterior to anterior, medial to the Achilles tendon and posterior to the tarsal tunnel. The tendon can be confirmed to be directly palpated in most patients, and, with motion of the hallux, the muscle encroachment can be felt and seen as the muscle bulges beneath the skin. Direct palpation from the medial side of the ankle is not sufficient to determine whether the pain results from the posterior tibial nerve or from the FHL. Another finding that suggests FHL stenosis is pseudohallux rigidus, which is loss of passive dorsiflexion of the hallux with ankle dorsiflexion, with support under the first metatarsal head simulating weight bearing.28

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic studies for defining FHL stenosis and tenosynovitis include MRI, ultrasonography, and tenography.14,23,31–33 The value of imaging studies is in their ability to rule out other causes of posteromedial ankle pain and to define causes of posterior ankle pain that may be associated, such as os trigonum or posterior soft tissue impingement. FHL stenosis can be associated with increased fluid around the entrance to the FHL tunnel and surrounding edema, as seen on a T2-weighted sequence in the sagittal or axial views. Although there can be a natural communication with the ankle joint, a discordant amount of fluid on MRI or ultrasonography suggests FHL tendonitis. Dynamic ultrasound studies can reveal the impingement: the normal linear striations of the tapered distal muscle belly become bunched up as it encroaches on the FHL tunnel.14,31 In some cases, the increased fluid may be seen as far distal as the midfoot, which on MRI is best seen on a coronal image.

Indications and Contraindications

Arthroscopic FHL release is indicated if pain is not relieved after conservative treatment. It is indicated for both isolated cases of FHL stenosis and those cases with other associated pathology of the posterior ankle. If indications for other procedures, such as tarsal tunnel release, are found along with FHL stenosis, an open approach should be chosen. Release of the tarsal tunnel from an endoscopic approach cannot be recommended at this time. The absence of a posterior tibial pulse behind the medial malleolus is an indication to assess the vascular anatomy through MRI review.

Treatment Options

Conservative Management

Nonoperative treatment of FHL tenosynovitis can include specific stretching exercises, a night splint, anti-inflammatory medications, ice, and activity modification or short-term immobilization.28 If these measures fail to provide satisfactory improvement or relief of pain within 6 to 8 weeks, release of the FHL sheath, with or without distal muscle débridement, can be considered. Ultrasound-guided injections of the tendon sheath have been described,31 but I do not advocate local steroid injection for this problem.

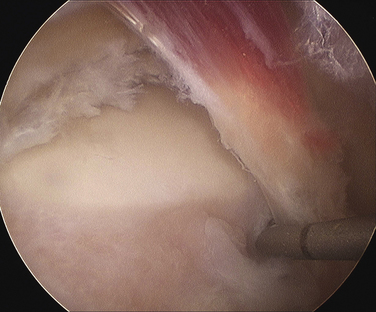

Arthroscopic Technique

Positioning and portal placement are the same as for any prone ankle arthroscopy procedure, as described previously. The FHL tendon is identified by movement of the hallux, and the amount of stenosis in full passive ankle and hallux dorsiflexion is observed. The degree of muscle débridement required can be considered based on this observation (see Fig. 8-16). The attachment of the fibrous tunnel on the posterolateral tubercle is released with an end-cutting arthroscopic débrider until the subtalar joint is visualized, indicating complete release of the tunnel from the talus (Fig. 8-17). At that point, the FHL is again examined through full passive dorsiflexion, and débridement of any low-lying muscle fibers is carefully performed. The suction on the débrider should be limited so as not to draw the adjacent perineural fat into the débrider tip. At the conclusion of the release and débridement, the FHL tendon should move freely through full passive motion, without any muscle impingement on the posterior talus (Fig. 8-18).

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol

Postoperative treatment consists of a soft compressive dressing and splinting of the ankle in neutral position in a removable cast boot. Full weight bearing is allowed and encouraged. Early active and passive motion is important for regaining FHL function. It is not uncommon for the patient to experience FHL weakness and a sense of loss of active control in the early postoperative period. Formal physical therapy can be helpful to retrain and strengthen the joint. A night splint may be used for several months or until full function returns and is helpful to avoid postoperative scarring in equinus during sleep.

Summary

Posterior ankle arthroscopy is a safe and effective method for releasing the FHL tunnel and relieving FHL stenosis.4,34,35 Minimal dissection allows for early return to function and less risk of wound problems. Associated pathology of the posterior ankle can be effectively treated simultaneously.

HAGLUND’S DEFORMITY

Posterior heel pain is related to a number of pathologies involving the Achilles tendon and its insertion.36 Insertional problems of the Achilles tendon include painful impingement of the tendon and associated bursitis over a prominence of the posterior-superior calcaneal tuberosity (Fig. 8-19). Haglund described a case of excision of this prominent bone and proposed impingement of the bone on the Achilles tendon as the etiology of retrocalcaneal bursitis. He recommended removal of the bony prominence in addition to excision of the bursa, which was advocated as sole treatment of the problem at that time.37 Essentially the same treatment was performed by various open approaches for the remainder of the 20th century. Several investigators have reported uniformly good results and few complications for the endoscopic excision of this bony impingement and bursa.38–44

Normal and Pathologic Anatomy

The upper third of the posterior surface of the calcaneus is composed of a pre-Achilles fibrocartilaginous bursal surface; the lower two thirds of the posterior calcaneal surface provides insertion for the Achilles tendon.45 Prominence of the bony surface of the upper third of this surface creates an impingement syndrome of the Achilles tendon which has been associated with tight shoes and hard heel counters. Associated bursal inflammation and Achilles tendon degeneration are the result of the chronic mechanical impingement.

Diagnostic Imaging

A lateral radiograph of the calcaneus may reveal a large bony prominence and intratendinous calcifications and may be helpful for surgical planning, especially if intraoperative fluoroscopy is used to judge resection of bone. MRI and ultrasonography can be helpful to determine the degree of tendon degeneration and bursal inflammation (see Fig. 8-19).

Indications and Contraindications

Endoscopic débridement of a Haglund deformity is indicated if nonoperative treatment has failed to relieve pain (reported in 10% to 50% of cases).39,42,46,47 Endoscopic treatment of posterior Achilles pathology is not indicated in cases where extensive tendinosis requires direct surgical débridement of the Achilles insertion with detachment and reattachment. However, Achilles tendinosis can be treated by percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy, which may extend the use of minimally invasive surgery in some cases.

Treatment Options

Conservative Management

Conservative treatment has been reported to be successful in 50% to 90% of cases of posterior heel pain; it may be less effective in cases of significant bony impingement.46,48 Achilles tendon stretching, night splints, gel pads, footwear modification, ice, anti-inflammatory medications, relative rest, immobilization, and injections have been reported to be of benefit. Steroid injections may help with pain caused by inflammation but are believed to carry a risk of weakening the Achilles tendon, potentially leading to rupture. If steroids are used, temporary immobilization for several weeks could help prevent tendon rupture. I do not recommend steroid injections around the Achilles tendon.

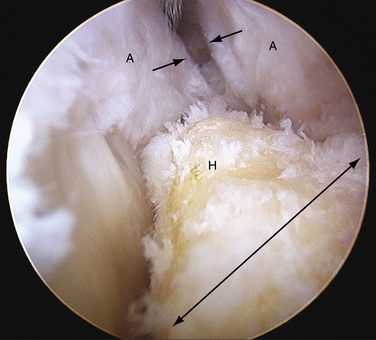

Endoscopic Technique

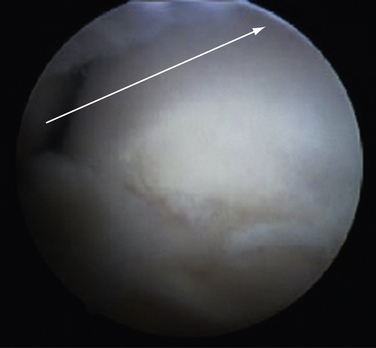

The technique of endoscopic Haglund resection has been described by several authors.38,39,41–44 Both supine and prone positions have been suggested. I prefer the supine position, because the most posterior portion of the resection is more ergonomically reached. Although it has been recommended to place the medial and lateral portals anterior to the tendon, I prefer to place them just anterior to the anterior surface of the central tendon, passing through the medial and lateral margins of the U-shaped insertion and directly into the pre-Achilles space (Figs. 8-20 and 8-21).49 The advantage of this position is that it allows the arthroscopic burr to easily pass parallel to the tendon insertion, creating a flush surface across the entire posterior calcaneus (Fig. 8-22). The initial débridement of the bursa and fibrofatty tissue dorsal to the calcaneal tuberosity allows for exposure of the Haglund deformity. After the soft tissues are cleared, the arthroscopic burr is used to remove all of the impinging bone. A fluoroscope can be used to confirm satisfactory resection of bone compared to the preoperative radiographs, and this can be compared with visual inspection (Fig. 8-23). Percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy can be used to treat associated degenerative Achilles tendon with visualization through the arthroscope (Fig. 8-24).50 Nonabsorbable sutures are used to close the portals, and a bulky soft dressing is used with a removable cast boot for immediate weight bearing. There should be no real risk of compromise to the tendon insertion, because the scope allows precise débridement up to the beginning of the tendon insertion. Elevation is encouraged for the first 48 hours to diminish the risk of significant bone bleeding postoperatively.

FIGURE 8-20 Endoscopic view of a Haglund deformity (H) of the same patient as in Figure 8-19. The line of resection is indicated by a long arrow. The short arrows demonstrate the location of the portal through the medial side of the U-shaped Achilles tendon insertion (A). This location allows for a direct line of action for the burr to débride down to the top of the central tendon insertion.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol

Because the insertion of the Achilles tendon is not compromised by an endoscopic approach for excision of the bony prominence, immediate partial weight bearing is allowed with crutches for comfort. In some cases, a short period in a removable cast boot facilitates mobilization. A night splint is used to avoid equinus. Physical therapy may begin 1 week after surgery, after the portals have become well sealed. A program of graduated strengthening and stretching is progressed over 4 to 6 weeks, and low-impact aerobic exercises, which can include pool therapy, are begun after the sutures are removed at about 2 weeks. Jogging on a treadmill is allowed as tolerated after 6 to 8 weeks, depending on whether percutaneous tenotomy was performed. Unrestricted athletic activity is allowed after 10 to 12 weeks.41,44 A maintenance program for stretching and focused strengthening of the soleus muscle is instituted for the next 6 months. A heel lift can be used during the first 6 weeks if the patient has a tight heel cord, but this does not obviate the need for a good preoperative and postoperative stretching program.39

1. Jerosch J. Subtalar arthroscopy—indications and surgical technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:122-128.

2. Van Dijk CN, Van Bergen CJ. Advancements in ankle arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:635-646.

3. Scholten PE, Sierevelt IN, Van Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2665-2672.

4. Willits K, Sonneveld H, Amendola A, et al. Outcome of posterior ankle arthroscopy for hindfoot impingement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:196-202.

5. Keeling JJ, Guyton GP. Endoscopic flexor hallucis longus decompression. a cadaver study, Foot Ankle Int. 282007 810-814.

6. Phisitkul P, Junko JT, Femino JE, et al. Technique of prone ankle and subtalar arthroscopy. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;6:30-37.

7. Bruns J, Eggers-Stroder G. Os trigonum syndrome. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1991;5:155-158.

8. Hamilton WG, Geppert MJ, Thompson FM. Pain in the posterior aspect of the ankle in dancers. differential diagnosis and operative treatment, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 781996 1491-1500.

9. Iovane A, Midiri M, Finazzo M, et al. Os trigonum tarsi syndrome. role of magnetic resonance, Radiol Med. 992000 36-40.

10. Kolettis GJ, Micheli LJ, Klein JD. Release of the flexor hallucis longus tendon in ballet dancers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1386-1390.

11. Sarrafian SK, editor. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. Descriptive, Topographic, Functional. 2nd ed. 1993 JB Lippincott Philadelphia, PA 47-55.

12. Sanders TG, Rathur SK. Impingement syndromes of the ankle. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 2008;16:29-38. v

13. Jones DM, Saltzman CL, El-Khoury G. The diagnosis of the os trigonum syndrome with a fluoroscopically controlled injection of local anesthetic. Iowa Orthop J. 1999;19:122-126.

14. Femino JE, Jacobson JA, Craig CL, Kuhns LR. Dynamic ultrasound of the foot and ankle. adult and pediatric applications, Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 62007 50-61.

15. Hedrick MR, McBryde AM. Posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:2-8.

16. Henderson I, La Valette D. Ankle impingement. combined anterior and posterior impingement syndrome of the ankle, Foot Ankle Int. 252004 632-638.

17. Jaivin JS, Ferkel RD. Arthroscopy of the foot and ankle. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13:761-783.

18. Koulouris G, Connell D, Schneider T, Edwards W. Posterior tibiotalar ligament injury resulting in posteromedial impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:575-583.

19. Liu SH, Mirzayan R. Posteromedial ankle impingement. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:709-711.

20. Sarrafian SK, editor. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. Descriptive, Topographic, Functional, 2nd ed. 1993 JB Lippincott Philadelphia, PA 159-186.

21. Bureau NJ, Cardinal E, Hobden R, Aubin B. Posterior ankle impingement syndrome. MR imaging findings in seven patients, Radiology. 2152000 497-503.

22. Lee JC, Calder JD, Healy JC. Posterior impingement syndromes of the ankle. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008;12:154-169.

23. Robinson P. Impingement syndromes of the ankle. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:3056-3065.

24. Hamilton WG. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus tendon and posterior impingement upon the os trigonum in ballet dancers. Foot Ankle. 1982;3:74-80.

25. Marotta JJ, Micheli LJ. Os trigonum impingement in dancers. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:533-536.

26. Sammarco GJ, Cooper PS. Flexor hallucis longus tendon injury in dancers and nondancers. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:356-362.

27. Kirane YM, Michelson JD, Sharkey NA. Contribution of the flexor hallucis longus to loading of the first metatarsal and first metatarsophalangeal joint. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:367-377.

28. Michelson J, Dunn L. Tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus. a clinical study of the spectrum of presentation and treatment, Foot Ankle Int. 262005 291-303.

29. Sarrafian SK, editor. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. Descriptive, Topographic, Functional. 2nd ed. 1993 JB Lippincott Philadelphia, PA 171-174.

30. Femino JE, Trepman E, Chisholm K, Razzano L. The role of the flexor hallucis longus and peroneus longus in stabilization of the ballet foot. J Dance Med Sci. 2000;4:86-89.

31. Mehdizade A, Adler RS. Sonographically guided flexor hallucis longus tendon sheath injection. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:233-237.

32. Na JB, Bergman AG, Oloff LM, Beaulieu CF. The flexor hallucis longus. tenographic technique and correlation of imaging findings with surgery in 39 ankles, Radiology. 2362005 974-982.

33. Peace KA, Hillier JC, Hulme A, Healy JC. MRI features of posterior ankle impingement syndrome in ballet dancers. a review of 25 cases, Clin Radiol. 592004 1025-1033.

34. Lui TH. Arthroscopy and endoscopy of the foot and ankle. indications for new techniques, Arthroscopy. 232007 889-902.

35. Van Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle pain. Instruct Course Lect. 2006;55:545-554.

36. Clain MR, Baxter DE. Achilles tendinitis. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:482-487.

37. Haglund P. Beitrag zur Klinik der Achillessehne. Zeitschr Orthop Chir. 1928;49:49-58.

38. Jerosch J, Schunck J, Sokkar SH. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty (ECP) as a surgical treatment of Haglund’s syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:927-934.

39. Leitze Z, Sella EJ, Aversa JM. Endoscopic decompression of the retrocalcaneal space. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1488-1496.

40. Lohrer H, Nauck T, Dorn NV, Konerding MA. Comparison of endoscopic and open resection for Haglund tuberosity in a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:445-450.

41. Morag G, Maman E, Arbel R. Endoscopic treatment of hindfoot pathology E13. Arthroscopy. 192003.

42. Van Dijk CN. Anterior and posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:663-683.

43. Van Dijk CN, Van Dyk GE, Scholten PE, Kort NP. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:185-189.

44. Ortmann FW, McBryde AM. Endoscopic bony and soft-tissue decompression of the retrocalcaneal space for the treatment of Haglund deformity and retrocalcaneal bursitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:149-153.

45. Sarrafian S, editor. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. Descriptive, Topographic, Functional. 2nd ed. 1993 JB Lippincott 60-65.

46. Davis PF, Severud E, Baxter DE. Painful heel syndrome. results of nonoperative treatment, Foot Ankle Int. 151994 531-535.

47. McGarvey WC, Palumbo RC, Baxter DE, Leibman BD. Insertional Achilles tendinosis. surgical treatment through a central tendon splitting approach, Foot Ankle Int. 232002 19-25.

48. Sammarco GJ, Taylor AL. Operative management of Haglund’s deformity in the nonathlete. a retrospective study, Foot Ankle Int. 191998 724-729.

49. Lohrer H, Arentz S, Nauck T, et al. The Achilles tendon insertion is crescent-shaped. an in vitro anatomic investigation, Clin Orthop Relat Res. 4662008 2230-2237.

50. Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G, et al. Results of percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy for Achilles tendinopathy in middle- and long-distance runners. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:835-840.