CHAPTER 62 Posterior abdominal wall and retroperitoneum

The posterior abdominal wall consists of fasciae, muscles and their vessels and spinal nerves; the overlying skin is continuous with that of the back. It is not easily defined, and is best described as that part of the abdominal wall lying between the two mid-dorsal lines, below the posterior attachments of the diaphragm and above the pelvis. It is continuous laterally with the anterolateral abdominal wall, superiorly with the posterior wall of the thorax behind the attachments of the diaphragm and inferiorly with the structures of the pelvis. The spinal column forms part of its structure and the muscles and fasciae of the back are closely related to it, especially posterolaterally.

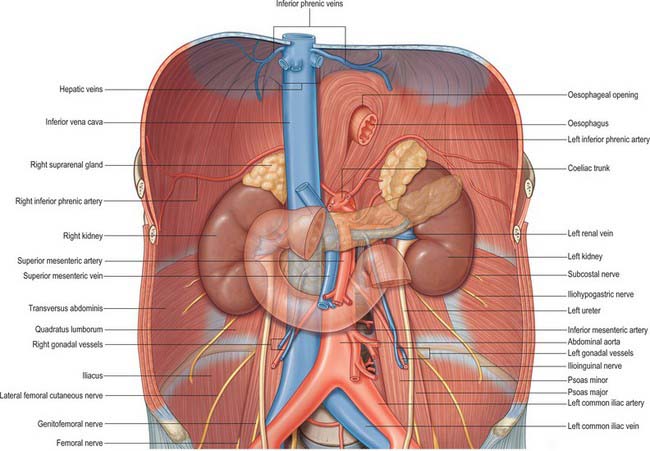

The major vessels and lymphatic channels, in addition to the peripheral autonomic nervous systems of the abdomen, pelvis and lower limbs lie on the posterior abdominal wall. These structures, together with several viscera (including the kidneys [Ch. 74], suprarenal glands [Ch. 72], pancreas [Ch. 70], ureters [Ch. 74] and parts of the gut tube [Chs 66 and 67]), lie beneath the posterior parietal peritoneum. These tissues and their surrounding connective and fascial planes are collectively referred to as the retroperitoneum.

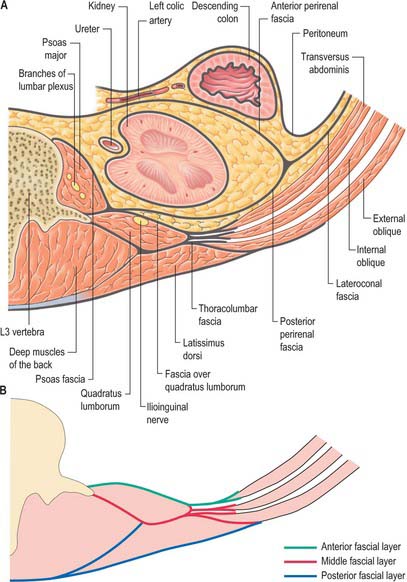

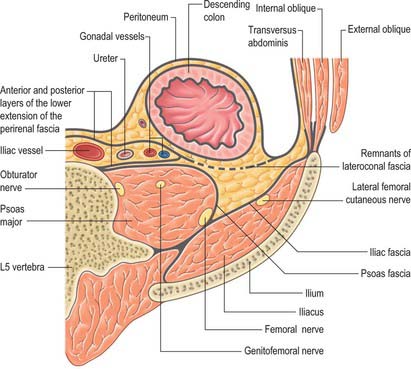

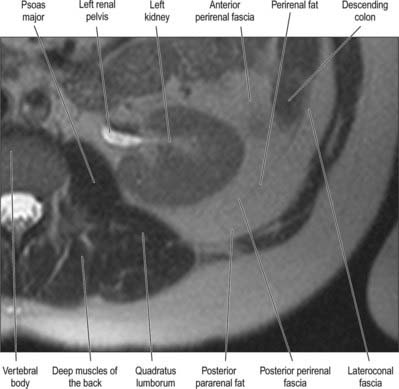

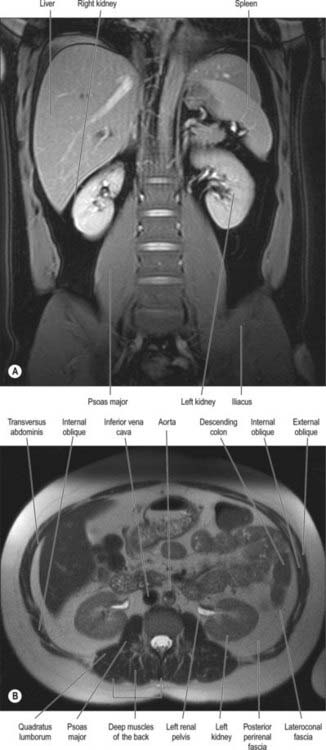

It has been suggested that the retroperitoneum can be divided into several spaces according to their relationships to the fascial layers that surround the kidneys and ureters. In this description, the layers of the perirenal fascia enclose a perirenal space containing the kidney, suprarenal gland, upper ureter and their neurovascular supply. The anterior layer of the perirenal fascia is continuous across the midline anterior to the main neurovascular structures of the retroperitoneum, and the right and left perirenal spaces communicate, although this channel is limited and contains many of the midline neurovascular structures of the retroperitoneum. Behind the posterior layer of the perirenal fascia lies the posterior pararenal space. Anterior to the anterior layer of the perirenal fascia lies the anterior pararenal space, in which lie several retroperitoneal parts of the gut tube, including the duodenum and pancreas. The anterior pararenal spaces are also continuous across the midline and are limited posteriorly by the anterior communicating layer of the perirenal fascia and anteriorly by the parietal peritoneum. This description helps to explain why moderate amounts of fluid, blood or pus collecting in the retroperitoneum tend to remain constrained within the space in which they are formed although, for pathological processes such as tumour invasion, the fascial planes provide a weak barrier to local spread (Figs 62.1, 62.2).

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUES

THORACOLUMBAR FASCIA

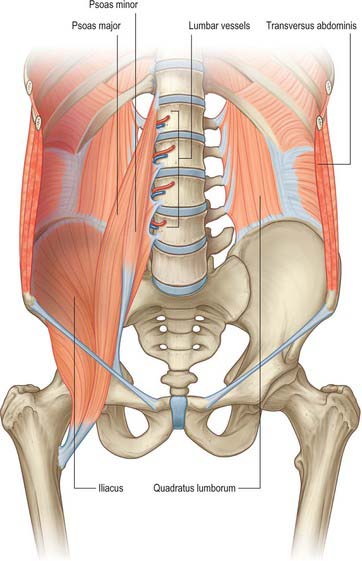

The thoracolumbar fascia in the lumbar region is in three layers (Figs 62.1, 62.2, 62.3). The posterior layer is attached to the spines of the lumbar and sacral vertebrae and to the supraspinous ligaments. The middle layer is attached medially to the tips of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae and the intertransverse ligaments, inferiorly to the iliac crest, and superiorly to the lower border of the 12th rib and the lumbocostal ligament. The anterior layer covers quadratus lumborum and is attached medially to the anterior surfaces of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae behind the lateral part of psoas major. Inferiorly, it is attached to the iliolumbar ligament and the adjoining part of the iliac crest. Superiorly, it is attached to the apex and inferior border of the 12th rib and then extends to the transverse process of the first lumbar vertebra, to form the lateral arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. The posterior and middle layers of the thoracolumbar fascia unite at the lateral margin of erector spinae. At the lateral border of quadratus lumborum they are joined by the anterior layer, to form the aponeurotic origin of transversus abdominis.

OTHER FASCIAL LAYERS

Perirenal fascia

The perirenal fascia is a multilaminated fascial layer that surrounds the kidney, suprarenal glands, upper ureter and associated fat, which all lie in the perirenal space (see Ch. 74). Although described as having anterior and posterior layers, these are continuous with each other laterally, and give rise to the lateroconal fascia at this point (Figs 62.1–62.3). The posterior layer of the renal fascia is adherent to the fascia over psoas major, the iliac fascia and the anterior layers of the thoracolumbar fascia. In the obese, there may be some loose adipose tissue between these layers, but it is rarely thick. The anterior part of the renal fascia separates the kidney and the perirenal space from the overlying anterior pararenal space and its associated viscera (on the right the duodenum, ascending colon and right colonic mesentery and on the left the duodenum, descending colon and left colonic mesentery). Inferiorly, the perirenal fascia continues down and encloses the ureter. It becomes progressively thinner towards the brim of the pelvis, where it is no longer distinguishable from the loose general connective tissue of the retroperitoneum.

MUSCLES

The majority of the muscles of the posterior abdominal wall are functionally part of the lower limb or vertebral column. They provide the surface against which the neurovascular structures of the retroperitoneum lie, and they are supported and separated from the majority of the retroperitoneal structures by fascial layers (Figs 62.4, 62.5; see Fig. 62.14).

Quadratus lumborum

Quadratus lumborum is attached below by aponeurotic fibres to the iliolumbar ligament and the adjacent portion of the iliac crest for approximately 5 cm. The superior attachment is to the medial half of the lower border of the 12th rib, and by four small tendons to the apices of the transverse processes of the upper four lumbar vertebrae. Sometimes it is also attached to the transverse process or body of the 12th thoracic vertebra. Occasionally, a second layer of this muscle is found in front of the first, attached to the upper borders of the transverse processes of the lower three or four lumbar vertebrae and to the lower margin and the lower part of the anterior surface of the 12th rib.

Erector spinae

The muscles of the erector spinae group (see Ch. 42) do not form part of the posterior abdominal wall itself, but are closely associated with the fascial layers of the posterior wall.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

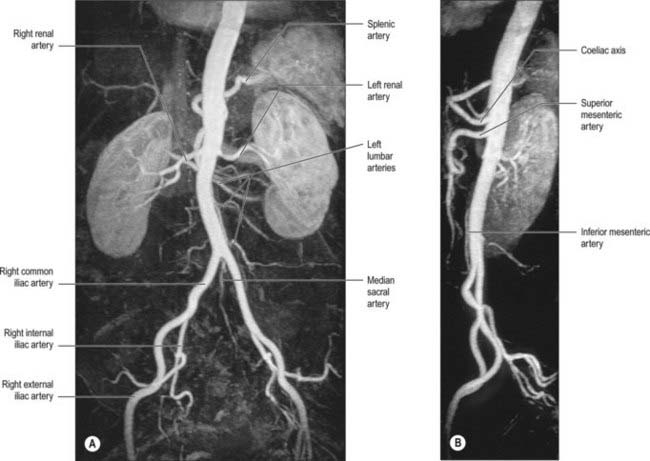

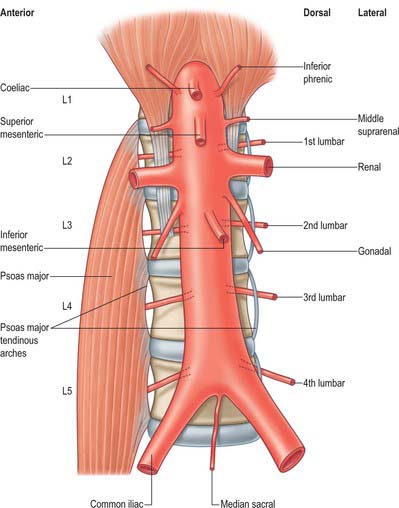

ABDOMINAL AORTA

The abdominal aorta begins at the median, aortic hiatus of the diaphragm, anterior to the inferior border of the 12th thoracic vertebra and the thoracolumbar intervertebral disc (Figs 62.6, 62.7). It descends anterior to the lumbar vertebrae to end at the lower border of the fourth lumbar vertebra, a little to the left of the midline, by dividing into two common iliac arteries. It diminishes rapidly in calibre from above downward, because its branches are large; however, the diameter of the vessel at any given height tends to increase slightly with age. The cadaveric superior and inferior calibres are between 9–14 mm and 8–12 mm, respectively, with little difference between the sexes. The angle of the aortic bifurcation varies widely, particularly in the elderly. It has been suggested that the relationship between aortic size and shape is a possible causative factor in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysm (Newman et al 1971). The reflection of transmitted pressure waves at junctions between vessels (of which the abdominal aorta has many) may focally weaken the intimal lining, e.g. at the aortic bifurcation, pressure oscillations and possibly turbulence may be set up as a result of differences in the luminal diameters of the common iliac arteries, producing reflected waves that may injure the intima of the distal abdominal aorta. The role of the relative calibres of the iliac arteries remains uncertain (Shah et al 1978).

Relations

The thoracolumbar intervertebral discs, the upper four lumbar vertebrae, intervening intervertebral discs and the anterior longitudinal ligament are all posterior to the abdominal aorta. Lumbar arteries arise from its dorsal aspect and cross posterior to it. The third and fourth (and sometimes second) left lumbar veins also cross behind it to reach the inferior vena cava. The aorta may overlap the anterior border of the left psoas major.

Branches

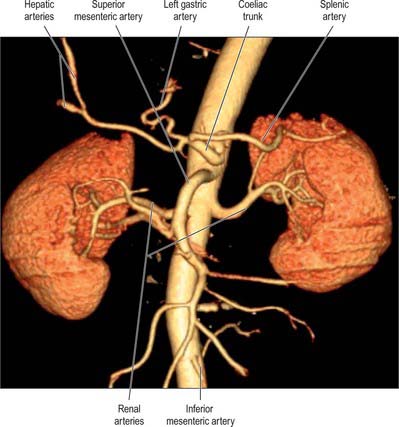

The branches of the aorta are described as anterior, lateral and dorsal (Fig. 62.8). The anterior and lateral branches are distributed to the viscera and the dorsal branches supply the body wall, vertebral column, vertebral canal and its contents. The aorta terminates by dividing into the right and left common iliac arteries.

Anterior group

Coeliac trunk

The coeliac trunk is the first anterior branch and arises just below the aortic hiatus at the level of T12/L1 vertebral bodies (Fig. 62.9). It is 1.5–2 cm long and passes almost horizontally forwards and slightly right above the pancreas and splenic vein. It divides into the left gastric, common hepatic and splenic arteries. The coeliac trunk may also give off one or both of the inferior phrenic arteries. The superior mesenteric artery may arise with the coeliac trunk as a common origin. One or more of the superior mesenteric branches may arise from the coeliac trunk. Anterior to the coeliac trunk lies the lesser sac. The coeliac plexus surrounds the trunk, sending extensions along its branches. On the right lie the right coeliac ganglion, right crus of the diaphragm and the caudate lobe of the liver. To the left lie the left coeliac ganglion, left crus of the diaphragm and the cardiac end of the stomach. The right crus may compress the origin of the coeliac trunk, giving the appearance of a stricture. The body of the pancreas and the splenic vein are inferior to the coeliac trunk.

Superior mesenteric artery

The superior mesenteric artery originates from the aorta approximately 1 cm below the coeliac trunk, at the level of the L1/2 intervertebral disc (Fig. 62.9). It lies posterior to the splenic vein and the body of the pancreas, and is separated from the aorta by the left renal vein. It runs inferiorly and anteriorly, anterior to the uncinate process of the pancreas and the third part of the duodenum.

Inferior mesenteric artery

The inferior mesenteric artery is usually smaller in calibre than the superior mesenteric artery. It arises from the anterior or left anterolateral aspect of the aorta at about the level of the third lumbar vertebra, 3 or 4 cm above the aortic bifurcation and posterior to the horizontal part of the duodenum (Figs 62.6, 62.9).

Dorsal group

Inferior phrenic arteries

The inferior phrenic arteries usually arise from the aorta, just above the level of the coeliac trunk. Occasionally they arise from a common aortic origin with the coeliac trunk, from the coeliac trunk itself or from the renal artery. They contribute to the arterial supply of the diaphragm. Each artery ascends and runs laterally anterior to the crus of the diaphragm, near the medial border of the suprarenal gland. The left passes behind the oesophagus and forwards on the left side of its diaphragmatic opening. The right passes posterior to the inferior vena cava and then along the right of the diaphragmatic opening for the inferior vena cava. Near the posterior border of the central tendon of the diaphragm, each divides into medial and lateral branches (Fig. 62.6). The medial branch curves forwards to anastomose with its fellow in front of the central tendon and with the musculophrenic and pericardiacophrenic arteries. The lateral branch approaches the thoracic wall, and anastomoses with the lower posterior intercostal and musculophrenic arteries. The lateral branch of the right artery provides the arterial supply to the wall of the inferior vena cava, whereas the left sends ascending branches to the serosal surface of the abdominal oesophagus. Each inferior phrenic artery has two or three small suprarenal branches. The capsule of the liver and spleen may also receive a small supply from the arteries.

Lumbar arteries

Dorsal branches

Each lumbar artery has a dorsal branch, which passes backwards between the adjacent transverse vertebral processes to supply the dorsal muscles of the back, the joints and skin of the back. This branch also has a spinal branch which enters the vertebral canal to supply its contents and adjacent vertebra, anastomosing with the arteries above and below it and across the midline (see Fig. 43.9). The spinal branch of the first lumbar artery supplies the terminal part of the spinal cord proper and the remainder supply the cauda equina, meninges and vertebral canal. Occlusion of all or most of these arteries by dissection or aneurysm of the abdominal aorta may cause ischaemia of the cauda equina, producing the so-called ‘cauda equina syndrome’. This is rare, however, even after infrarenal aortic graft surgery, because of the relatively good collateral circulation of the spinal cord arteries from the descending thoracic aorta. Branches of the lumbar arteries and their dorsal branches supply the adjacent muscles, fasciae, bones, haemopoeitic marrow, ligaments and joints of the vertebral column.

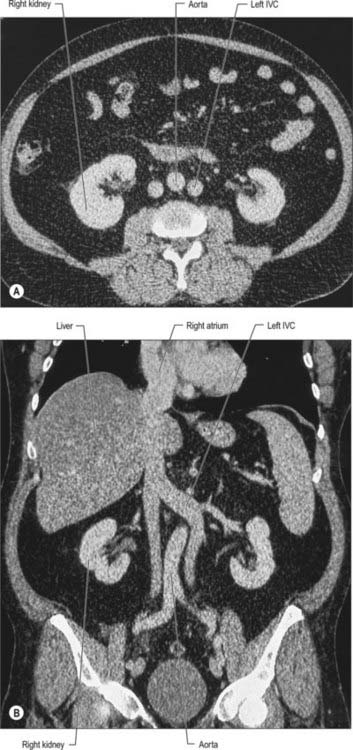

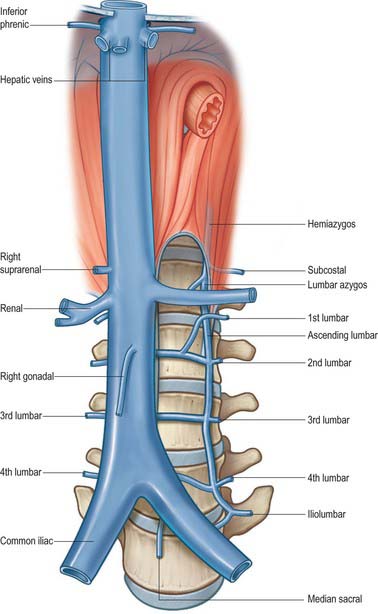

INFERIOR VENA CAVA

The inferior vena cava conveys blood to the right atrium from all structures below the diaphragm (Fig. 62.10). The majority of its course is within the abdomen, but a small section lies within the fibrous pericardium in the thorax.

Relations of the abdominal part of the inferior vena cava

Numerous anomalies may occur in the anatomy of the inferior vena cava, mostly related to its complex formation. It is sometimes replaced, below the level of the renal veins, by two more or less symmetric vessels (Fig. 62.11), often associated with the failure of interconnection between the common iliac veins, and persistence on the left of a longitudinal channel (usually the supracardinal or subcardinal vein) that normally disappears in early fetal life. In complete visceral transposition, the inferior vena cava lies to the left of the aorta.

Tributaries

The abdominal inferior vena cava usually receives the common iliac veins at its origin and the lumbar, right gonadal, renal, right suprarenal, inferior phrenic and hepatic veins during its course (Figs 62.6, 62.12).

Renal veins

The renal veins are large calibre vessels, which lie anterior to the renal arteries and open into the inferior vena cava almost at right angles (Fig. 62.10). The left is three times longer than the right in length (7.5 cm and 2.5 cm, respectively). The left vein lies on the posterior abdominal wall posterior to the splenic vein and body of the pancreas. Close to its opening into the inferior vena cava, it lies anterior to the aorta with the superior mesenteric artery just above it. The right renal vein lies posterior to the second part of the duodenum and sometimes the lateral part of the head of the pancreas.

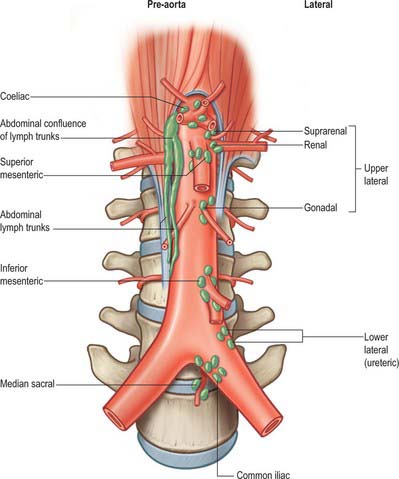

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

The lymphatic drainage of the abdominal viscera occurs almost exclusively through the cisterna chyli and the thoracic duct. Some lymphatic drainage may occur across the diaphragm from the bare area of the liver and the uppermost retroperitoneal tissues, but this is probably of little clinical consequence other than during obstruction of the thoracic duct. The lymph nodes of the retroperitoneum lie around the abdominal aorta and form pre-aortic, lateral aortic and retro-aortic groups (Fig. 62.13). Collectively, they are referred to as the para-aortic lymph nodes and clinically it is difficult to distinguish between them, either at operation or on cross-sectional imaging.

Cisterna chyli and abdominal lymph trunks

Lateral aortic group

The lateral aortic nodes lie on either side of the abdominal aorta anterior to the medial margins of psoas major, diaphragmatic crura and sympathetic trunks. On the right, some nodes lie lateral and anterior to the inferior vena cava near the end of the right renal vein. Nodes rarely lie between the aorta and inferior vena cava where they are closely related. The lateral aortic nodes drain the viscera and other structures supplied by the lateral and dorsal aortic branches. The upper lateral groups receive the lymph drainage directly from the suprarenal glands, kidneys, ureters, gonads, uterine tubes and upper uterus. They also receive lymph directly from the deeper tissues of the posterior abdominal wall. Lymphatics from the pelvis, most of the pelvic viscera, the perineum and the anterolateral abdominal wall pass first to regional nodes largely related to the iliac arteries and their branches. These include the common iliac, external iliac, internal iliac and circumflex iliac nodes, in addition to the inferior epigastric and sacral nodes. Lymph from the lower limbs passes through the pelvic lymph nodes via the iliac groups.

INNERVATION

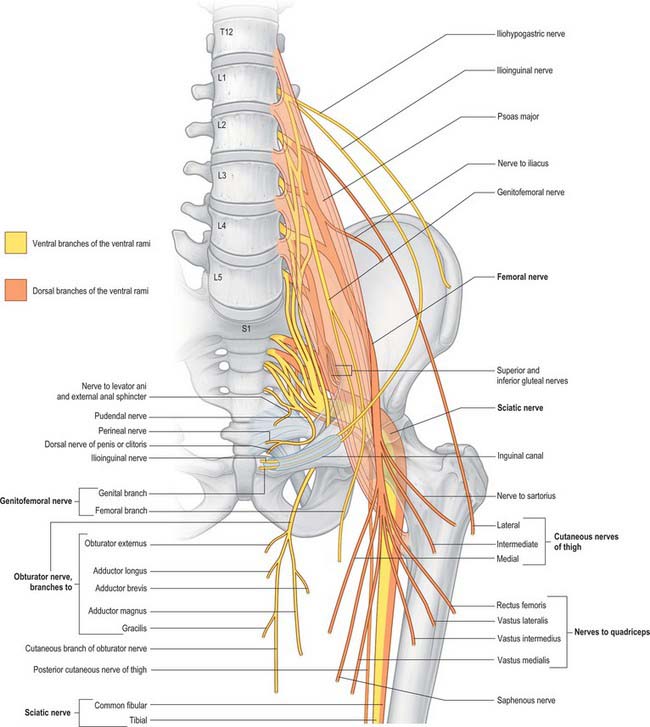

The posterior abdominal wall contains the origin of the lumbar plexus and numerous autonomic plexuses and ganglia, which lie close to the abdominal aorta and its branches (Fig. 62.14).

LUMBAR PLEXUS

The lumbar plexus lies within the substance of the posterior part of psoas major, anterior to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae and in ‘line’ with the intervertebral foramina (Fig. 62.15). It is formed by the first three, and most of the fourth, lumbar ventral rami, with a contribution from the 12th thoracic ventral ramus. Although there may be minor variations, the most common arrangement of the plexus is described here.

The first lumbar ventral ramus, joined by a branch from the 12th thoracic ventral ramus, bifurcates, and the upper and larger part divides again into the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. The smaller lower part unites with a branch from the second lumbar ventral ramus to form the genitofemoral nerve. The remainder of the second, third, and part of the fourth, lumbar ventral rami join the plexus and divide into ventral and dorsal branches. Ventral branches of the second to fourth rami join to form the obturator nerve. The main dorsal branches of the second to fourth rami join to form the femoral nerve. Small branches from the dorsal branches of the second and third rami join to form the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The accessory obturator nerve, when it exists, arises from the third and fourth ventral branches. The lumbar plexus is supplied by branches from the lumbar vessels which supply psoas major.

| Muscular | T12, L1–4 |

| Iliohypogastric | L1 |

| Ilioinguinal | L1 |

| Genitofemoral | L1, L2 |

| Lateral femoral cutaneous | L2, L3 |

| Femoral | L2–4 dorsal divisions |

| Obturator | L2–4 ventral divisions |

| Accessory obturator | L2, L3 |

Division of constituent ventral rami into ventral and dorsal branches is not as clear in the lumbar and lumbosacral plexuses as it is in the brachial plexus. Anatomically, the obturator and tibial nerves (via the sciatic) arise from ventral divisions, and the femoral and fibular nerves (via the sciatic) from dorsal divisions. Lateral branches of the 12th thoracic and first lumbar ventral rami are drawn into the gluteal skin, but otherwise these nerves are typical. The second lumbar ramus is difficult to interpret. It not only contributes substantially to the femoral and obturator nerves, but also has an anterior terminal branch (the genital branch of the genitofemoral) and a lateral cutaneous branch (lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the femoral branch of the genitofemoral). Anterior terminal branches of the third to fifth lumbar and first sacral rami are suppressed, but the corresponding parts of the second and third sacral rami supply the skin, etc. of the perineum.

Iliohypogastric nerve

The iliohypogastric nerve originates from the L1 ventral ramus. It emerges from the upper lateral border of psoas major, crosses obliquely behind the lower renal pole and in front of quadratus lumborum. Above the iliac crest, it enters the posterior part of transversus abdominis. Between transversus abdominis and internal oblique, it divides into lateral and anterior cutaneous branches, and also supplies both muscles. The lateral cutaneous branch runs through internal and external oblique above the iliac crest, a little behind the iliac branch of the 12th thoracic nerve, and is distributed to the posterolateral gluteal skin. The anterior cutaneous branch runs between and supplies internal oblique and transversus abdominis. It runs through internal oblique approximately 2 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, and through the external oblique aponeurosis approximately 3 cm above the superficial inguinal ring, and is then distributed to the suprapubic skin. The iliohypogastric nerve connects with the subcostal and ilioinguinal nerves (see Fig. 61.4). The nerve is occasionally injured during an oblique surgical approach to the appendix, but there is rarely any detectable sensory loss because the suprapubic skin is innervated from several sources. Division of the iliohypogastric nerve above the anterior superior iliac spine may weaken the posterior wall of the inguinal canal and predispose to formation of a direct hernia.

Femoral nerve

The femoral nerve descends through psoas major and emerges low on its lateral border. It passes between psoas major and iliacus deep to the iliac fascia and runs posterior to the inguinal ligament into the thigh. It gives off branches which supply iliacus and pectineus and sends sensory fibres to the femoral artery. Posterior to the inguinal ligament, it lies lateral to the femoral artery and is separated from it by a part of psoas major. The further course and distribution of the femoral nerve is described in Chapter 80.

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh emerges from the lateral border of psoas major and crosses iliacus obliquely towards the anterior superior iliac spine. It supplies sensory fibres to the parietal peritoneum in the iliac fossa. The right nerve passes posterolateral to the caecum, separated from it by the iliac fascia and peritoneum. The left nerve passes behind the lower part of the descending colon. Both nerves pass behind or through the inguinal ligament approximately 1 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and anterior to, or through, sartorius into the thigh. The further course and distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is described in Chapter 80.

Obturator nerve

The obturator nerve descends within the substance of psoas major to emerge from its medial border at the level of the pelvic brim. It passes posterior to the common iliac vessels and lateral to the internal iliac vessels. It then descends on the lateral wall of the pelvis attached to the fascia over obturator internus and lies anterosuperior to the obturator vessels before running into the obturator foramen to enter the thigh. It has no branches in the abdomen or pelvis. The further course and distribution of the obturator nerve is described in Chapter 80.

LUMBOSACRAL PLEXUS

The lumbosacral plexus provides the nerve supply to the pelvis and lower limb, in addition to part of the autonomic supply to the pelvic viscera. It gives origin to the sciatic, inferior gluteal, superior gluteal and pudendal nerves and the nerves to quadratus femoris, obturator internus and the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh. The further course and distribution of these nerves is described in Chapter 80.

Burkhill GJC, Healy JC. Anatomy of the retroperitoneum. Imaging. 2000;12:10-20.

Newman DL, Gosling RG, Bowden R. Changes in aortic distensibility and area ratio with the development of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1971;14:231-240.

Pick J. The Autonomic Nervous System. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1970.

Shah PM, Scarton HA, Tsapogas MJ. Geometric anatomy of the aorto-common iliac bifurcation. J Anat. 1978;126:451-458.