Chapter 7 Positive Mental Attitude

Introduction

Introduction

A positive mental attitude is one of the important foundational elements of good health. This axiom has been contemplated by philosophers and physicians since the time of Plato and Hippocrates. In addition to simple conventional wisdom, modern research has also verified the important role that attitude—the collection of habitual thoughts and emotions—plays in determining the length and quality of life. Specifically, studies using various scales to assess attitude, including the Optimism–Pessimism (PSM) scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), have shown that individuals with a pessimistic explanatory style have poorer health, are prone to depression, are more frequent users of medical and mental health care delivery systems, exhibit more cognitive decline and impaired immune function with aging, and have a shorter survival rate compared to optimists.1–8 One of the most recent studies involved a large cohort of 5566 people who completed a survey at two time points, aged 51–56 years at Time 1 and 63–67 years at Time 2. This survey included a questionnaire to determine positive psychological well-being by measuring self-acceptance, autonomy, purpose in life, positive relationships with others, environmental mastery, and personal growth. The results showed that people with low positive well-being were 7.16 times more likely to be depressed 10 years later.9 This research highlighted the fact that although life is full of events that are beyond one’s control, people can control their responses to such events. Attitude goes a long way toward determining how people view and respond to the stresses and challenges of life.

Attitude is reflected by explanatory style, a term developed by noted psychologist Martin Seligman to describe a cognitive personality variable that reflects how people habitually explain the causes of life events.8 Explanatory style was used to explain individual differences in response to negative events during the attributional reformulation of the learned helplessness model of depression developed by Seligman (described in Chapter 142).

Attitude, Personality, Emotions, and Immune Function

Attitude, Personality, Emotions, and Immune Function

Studies examining immune function in optimists versus pessimists have demonstrated significantly better immune function in the optimists. Specifically, studies have shown that optimists have increased secretory immunoglobulin-A function, natural killer cell activity, and cell-mediated immunity, which is demonstrated by better ratios of helper to suppressor T-cells than those of pessimists.5,10–13

The immune system is so critical to preventing cancer that, if emotions and attitude were risk factors for cancer, one would expect to see an increased risk of cancer in people who have long-standing depression or a pessimistic attitude. Research supports this association; for example, smokers who are depressed have a much greater risk of lung cancer than smokers who are not depressed.14

Depression and the harboring of other negative emotions contribute to an increased risk of cancer in several ways. Most research has focused on the impact of depression and other negative emotions on natural killer cells. Considerable scientific evidence has now documented the link between a higher risk of cancer and negative emotions, stress, and a low level or activity of natural killer cells.15 Negative emotions and stress paralyze many aspects of immune function and literally can cause natural killer cells to burst.15,16 Furthermore, the prototypical cancer personality—an individual who suppresses anger, avoids conflicts, and has a tendency to have feelings of helplessness—has lower natural killer cell activity than other personality types.12,13 These studies also indicate that individuals with a personality type that is prone to cancer have an exaggerated response to stress, which compounds the detrimental effects stress has on natural killer cells and the entire immune system.

Depression and stress not only affect the immune system but also appear to hinder the cell’s ability to repair damage to DNA. Most carcinogens cause cancer by directly damaging DNA in cells, thereby producing abnormal cells. One of the most important protective mechanisms against cancer in the cell’s nucleus is the enzymes responsible for the repair or destruction of damaged DNA. Several studies have shown that depression and stress alter these DNA repair mechanisms; for example, in one study, lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) from depressed patients demonstrated impairment in the ability to repair cellular DNA damaged by exposure to x-rays.17,18

Just as research has identified personality, emotional, and attitude traits that are associated with impaired immune function, likewise the field of psychoneuroimmunology has identified a collection of “immune power” traits that include a positive mental attitude, an effective strategy for dealing with stress, and a capacity to confide traumas, challenges, and feelings to oneself and others.15,19

Attitude and Cardiovascular Health

Attitude and Cardiovascular Health

In addition to the brain and immune system, the cardiovascular system is another body structure intricately tied to emotions and attitude. The relationship of an optimistic or pessimistic explanatory style with incidence of coronary heart disease was examined as part of the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study, an ongoing cohort study of older men.7 These men were assessed by the MMPI PSM scale. During an average 10-year follow up, 162 cases of incident coronary heart disease occurred: 71 cases of incident nonfatal myocardial infarction, 31 cases of fatal coronary heart disease, and 60 cases of angina pectoris. Men reporting high levels of optimism had a 45% lower risk for angina pectoris, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease death than men reporting high levels of pessimism. Interestingly, a clear dose–response relationship was found between levels of optimism and each outcome.

To illustrate how closely the cardiovascular system is linked to attitude, one study showed that measures of optimism and pessimism affected something as simple as ambulatory blood pressure.20 Pessimistic adults had higher blood pressure levels and felt more negative and less positive than optimistic adults. These results suggest that pessimism has broad physiologic consequences.

Attitude and Self-Actualization

Attitude and Self-Actualization

Maslow discovered that healthy individuals are motivated toward self-actualization, a process of “ongoing actualization of potentials, capacities, talents, as fulfillment of a mission (or call, fate, destiny, or vocation), as a fuller knowledge of, and acceptance of, the person’s own intrinsic nature, as an increasing trend toward unity, integration, or synergy within the person.”21

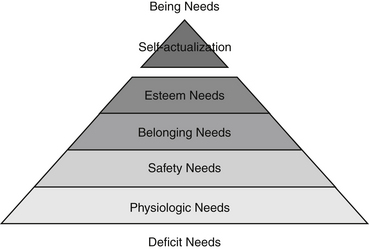

Maslow developed a five-step pyramid of human needs in which personality development progresses from one step to the next. The needs of the lower levels must be satisfied before the next level can be achieved. When needs are met, the individual moves toward well-being and health. Figure 7-1 displays Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

In modern life, a person’s occupation often correlates with the ability to achieve these needs. Table 7-1 provides an application of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in an occupational environment.

TABLE 7-1 Practical Application of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

| LEVEL OF NEED | GENERAL REWARDS | OCCUPATIONAL FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Self-actualization | Growth Achievement Advancement Creativity |

Challenging job Opportunities for creativity Achievement in work Promotion |

| Self-esteem | Self-respect Status Prestige |

Social recognition Job title High status of job Feedback from the job itself |

| Belonging | Love Friendship Belongingness |

Work groups or teams Supervision Professional associations |

| Safety | Security Stability Protection |

Health and safety Job security Contract of employment |

| Physiologic | Food Water Sleep Sex |

Pay Working conditions |

• Self-actualized people perceive reality more effectively than others and are more comfortable with it. They have an unusual ability to detect the spurious, the fake, and the dishonest in personality. They judge experiences, people, and things correctly and efficiently. They possess an ability to be objective about their own strengths, possibilities, and limitations. This self-awareness enables them to clearly define values, goals, desires, and feelings. They are not frightened by uncertainty.

• Self-actualized people have an acceptance of self, others, and nature. They can accept their own human shortcomings without condemnation. They do not have an absolute lack of guilt, shame, sadness, anxiety, and defensiveness, but they do not experience these feelings to unnecessary or unrealistic degrees. When they do feel guilty or regretful, they do something about it. Generally, they do not feel bad about discrepancies between what is and what ought to be.

• Self-actualized people are relatively spontaneous in their behavior and even more spontaneous in their inner life, thoughts, and impulses. They are unconventional in their impulses, thoughts, and consciousness. They are rarely nonconformists, but they seldom allow convention to keep them from doing anything they consider important or basic.

• Self-actualized people have a problem-solving orientation toward life instead of a self orientation. They commonly have a mission in life, some problem outside themselves that enlists much of their energies. In general, this mission is unselfish and is involved with the philosophical and ethical.

• Self-actualized people have a quality of detachment and a need for privacy. Often it is possible for them to remain above the battle, to be undisturbed by what upsets others. They are self-governing people who find meaning in being active, responsible, self-disciplined, and decisive rather than being pawns or helplessly ruled by others.

• Self-actualized people have a wonderful capacity to appreciate the basic pleasures of life, such as nature, children, music, and sex, again and again. They approach these basic experiences with awe, pleasure, wonder, and even ecstasy.

• Self-actualized people commonly have mystical or “peak” experiences, times of intense emotions in which they transcend the self. During a peak experience, they have feelings of limitless horizons and unlimited power while simultaneously feeling more helpless than ever before. There is a loss of place and time, and feelings of great ecstasy, wonder, and awe. The peak experience ends with the conviction that something extremely important and valuable has happened, so that the person is transformed and strengthened by the experience to some extent.

• Self-actualized people have deep feelings of identification with, sympathy for, and affection for other people despite occasional anger, impatience, or disgust.

• Self-actualized people have deeper and more profound interpersonal relationships than most other adults, but not necessarily deeper than children’s. They are capable of more closeness, greater love, more perfect identification, and more erasing of ego boundaries than other people would consider possible. One consequence is that self-actualized people have especially deep ties with relatively few individuals, and their circle of friends is small. They tend to be kind or at least patient with almost everyone, yet they speak realistically and harshly of those who they feel deserve it, especially hypocritical, pretentious, pompous, or self-inflated individuals.

• Self-actualized people are democratic in the deepest possible sense. They are friendly toward everyone, regardless of class, education, political beliefs, race, and color. They believe it is possible to learn something from everyone. They are humble, in the sense of being aware of how little they know in comparison with what could be known and what is known by others.

• Self-actualized people are strongly ethical and moral. However, their notions of right and wrong and good and evil are often unconventional. For example, a self-actualized person would never consider segregation, apartheid, or racism to be morally right although it may be legal.

• Self-actualized people have a keen, unhostile sense of humor. They do not laugh at jokes that hurt other people or are aimed at others’ inferiority. They can make fun of others in general or of themselves when they are foolish or try to be big when they are small. They are inclined toward thoughtful humor that elicits a smile, is intrinsic to the situation, and is spontaneous.

• Self-actualized people are highly imaginative and creative. The creativeness of a self-actualized individual is not of the special talent type, such as Mozart’s, but rather is similar to the naive and universal creativeness of unspoiled children.

Clinical Aspects of Learned Optimism

Clinical Aspects of Learned Optimism

The new psychology that Maslow’s work referred to may turn out to be “positive clinical psychology”.22 This field of practice was born in 1998 when Martin Seligman chose it as the theme for his term as president of the American Psychological Association.23 Positive clinical psychology aims to change clinical psychology to have an equally weighted focus on both positive and negative functioning.24 The approach is based on five key bodies of empirical findings: (1) the absence of positive well-being leads to the development of disorder over time9; (2) the absence of positive characteristics predicts disorder above and beyond the presence of negative characteristics9; (3) positive characteristics interact with negative life events to predict disorder (so studying only negative life events would produce misleading results)25; (4) many aspects of well-being range from extremely negative functioning, through a neural midpoint, to positive well-being (possibly including happiness to depression and anxiety to relaxation continuums),26 making it impossible to study exclusively negative or positive well-being; and (5) positive interventions can be as effective as other more commonly used approaches such as cognitive therapy.27

Positive clinical psychology ultimately involves helping patients become optimistic, which according to Martin Seligman, the world’s leading authority on attitude and explanatory style, is our natural tendency.28 Optimism not only is a necessary step toward achieving optimal health, as emphasized in the preceding, but is also critical to happiness and a higher quality of life.

• Help them become aware of self-talk. Tell them that all people conduct a constant running dialogue in their heads. In time, the things people say to themselves and others percolate down into their subconscious minds. Those inner thoughts, in turn, affect the way people think and feel. Naturally, a steady stream of negative thoughts will have a negative effect on a person’s mood, immune system, and quality of life. The cure is to become aware of self-talk and then to consciously work to feed positive self-talk messages to the subconscious mind.

• Help them ask better questions. The quality of a person’s life is equal to the quality of the questions habitually asked. For example, if a person experiences a setback, does he or she think “Why am I so stupid? Why do bad things always happen to me?” or “Okay, what can be learned from this situation so that it never happens again? What can I do to make the situation better?” Clearly, the latter response is healthier. Regardless of the situation, asking better questions is bound to improve one’s attitude. Some examples of questions that can improve attitude and self-esteem when asked regularly include:

• Help them set positive goals. Learning to set achievable goals is a powerful method for building a positive attitude and raising self-esteem. Achieving goals creates a success cycle: a person feels better about himself or herself, and the better he or she feels, the more likely he or she is to succeed. Some guidelines for helping patients set health goals follow:

• Help them experience gratitude. A large body of recent work has suggested that people who are more grateful have higher levels of well-being, are happier, less depressed, less stressed, and more satisfied with their lives and social relationships.29,30 Gratitude appears to be one of the strongest links with mental health of any character trait. Helping to instill a sense of gratitude has been shown to be a very successful intervention. In one study, participants were randomly assigned to one of six therapeutic interventions designed to improve the participant’s overall quality of life.31 Of these six interventions, it was found that the biggest short-term effects came from a “gratitude visit,” where participants wrote and delivered a letter of gratitude to someone in their life. This simple gesture showed a rise in happiness scores by 10% and a significant fall in depression scores, results which lasted up to 1 month after the visit. The act of writing “gratitude journals,” in which participants wrote down three things they were grateful for every day had longer lasting effects on happiness scores. The greatest benefits with this practice were usually found to occur around 6 months after it began. Similar practices have shown comparable benefits.

Counseling is necessary for the severely pessimistic individual. Forms of cognitive therapy appear to be the most useful therapy at this time. Cognitions comprise the whole system of thoughts, beliefs, mental images, and feelings. Cognitive therapy can be as effective as the use of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of moderate depression; in addition, there tends to be a lower risk of relapse—the return of depression—with cognitive therapy.32 One reason for this is that cognitive therapy teaches people practical skills they can use to combat depression any time, anywhere, and every day for the rest of their lives. Cognitive therapy avoids the long, drawn out (and expensive) process of psychoanalysis. It is a practical, solution-oriented psychotherapy that teaches skills a person can apply to improve quality of life.

• Recognize the automatic negative thoughts that flit through consciousness at the times when they feel the worst.

• Dispute the negative thoughts by focusing on contrary evidence.

• Learn a different explanation to dispute the automatic negative thoughts.

• Avoid rumination (the constant churning of a thought in one’s mind) by helping the patient better control his or her thoughts.

• Question depression-causing negative thoughts and beliefs, and replace them with empowering positive thoughts and beliefs.

1. Maruta T., Colligan R.C., Malinchoc M., Offord K.P. Optimism-pessimism assessed in the 1960s and self-reported health status 30 years later. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:748–753.

2. Taylor S.E., Kemeny M.E., Reed G.M., et al. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. Am Psychol. 2000;55:99–109.

3. Schweizer K., Beck-Seyffer A., Schneider R. Cognitive bias of optimism and its influence on psychological well-being. Psychol Rep. 1999;84:627–636.

4. Chang E.C., Sanna L.J. Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: a test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:524–531.

5. Segerstrom S.C. Optimism, goal conflict, and stressor-related immune change. J Behav Med. 2001;24:441–467.

6. Maruta T., Colligan R.C., Malinchoc M., Offord K.P. Optimists vs pessimists: survival rate among medical patients over a 30-year period. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:140–143.

7. Kubzansky L.D., Sparrow D., Vokonas P., Kawachi I. Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:910–916.

8. Peterson C., Seligman M., Valliant G. Pessimistic explanatory style as a risk factor for physical illness: a thirty-five year longitudinal study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:23–27.

9. Wood A.M., Joseph S. The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: a ten year cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:213–217.

10. Brennan F.X., Charnetski C.J. Explanatory style and immunoglobulin A (IgA). Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2000;35:251–255.

11. Kamen-Siegel L., Rodin J., Seligman M.E., Dwyer J. Explanatory style and cell-mediated immunity in elderly men and women. Health Psychol. 1991;10:229–235.

12. Imai K., Nakachi K. Personality types, lifestyle, and sensitivity to mental stress in association with NK activity. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2001;204:67–73.

13. Segerstrom S.C. Personality and the immune system: models, methods, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:180–190.

14. Jung W., Irwin M. Reduction of natural killer cytotoxic activity in major depression: interaction between depression and cigarette smoking. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:263–270.

15. Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., McGuire L., Robles T.F., Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:83–107.

16. Maddock C., Pariante C.M. How does stress affect you? An overview of stress, immunity, depression and disease. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc. 2001;10:153–162.

17. Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., Stephens R., Lipitz P., et al. Distress and DNA repair in human lymphocytes. J Behav Med. 1985;8:311–320.

18. Glaser R., Thorn B.E., Tarr K.L., et al. Effects of stress on methyltransferase synthesis: an important DNA repair enzyme. Health Psychol. 1985;4:403–412.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology and cancer: fact or fiction? Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1603–1607.

20. Raikkonen K., Matthews K.A., Flory J.D., et al. Effects of optimism, pessimism, and trait anxiety on ambulatory blood pressure and mood during everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76:104–113.

21. Maslow A. The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking; 1971.

22. Lambert M.J., Erekson D.M. Positive psychology and humanistic tradition. J Psychother Integration. 2008;18:222–232.

23. Seligman M.E.P., Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5–14.

24. Wood A.M., Tarrier N. Positive clinical psychology: a new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010 Nov;30(7):819–829.

25. Johnson J., Gooding P.A., Wood A.M., et al. Resilience to suicidal ideation in psychosis: positive self-appraisals buffer the impact of hopelessness. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(9):883–889.

26. Wood A.M., Taylor P.T., Joseph S. Does the CES-D measure a continuum from depression to happiness? Comparing substantive and artifactual models. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:120–123.

27. Geraghty A.W.A., Wood A.M., Hyland M.E. Attrition from self-directed interventions: Investigating the relationship between psychological predictors, intervention content and dropout from a body dissatisfaction intervention. Social Sci Med. 2009;71:31–37.

28. Seligman M. Learned optimism. New York: Knopf; 1991.

29. Wood A.M., Froh J.J., Geraghty A.W. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010 Nov;30(7):890–905.

30. Wood A.M., Joseph S., Maltby J. Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the big five facets personality and individual differences. 2009;46:443–447.

31. Seligman M.E.P., Steen T.A., Park N., Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol. 2005;60:410–421.

32. Casacalenda N., Perry J.C., Looper K. Remission in major depressive disorder: a comparison of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and control conditions. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1354–1360.