Positioning and Nerve Injury

Positioning the Patient

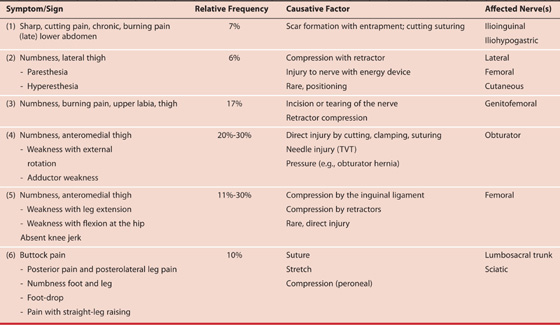

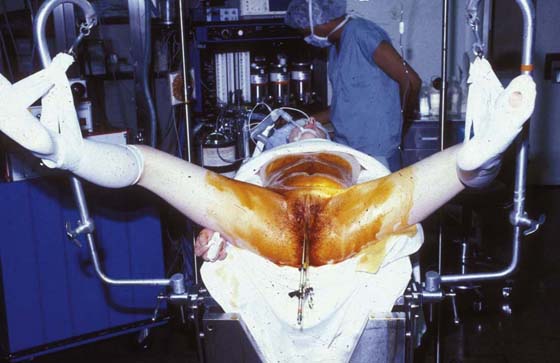

Proper care in positioning patients for cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, uterine, and endoscopic surgery is of vital interest for the gynecologic surgeon. The dorsal lithotomy position regardless of whether it is implemented with a candy cane or Allen, or knee-crutch leg supports remains an unnatural state Figs. 6–1 through 6–3. When lithotomy position is coupled with the Trendelenburg position, additive abnormalities may ensue. Improper positioning can and will result in neurologic injury. Table 6–1 illustrates the frequency, causative factor(s), and specific locations of nerve injuries associated with obstetric and gynecologic surgery. The proper lithotomy position includes thighs and legs gently flexed; ankles and feet evenly supported; and avoidance of dorsiflexion of the foot, minimal abduction at the hip, buttocks firmly seated on the operating table, avoidance of overhanging buttocks, and knees (lateral) free from contact with leg support devices. Several lithotomy positions are acceptable. A low lithotomy position is quite satisfactory for dilation and curettage, hysteroscopy, and cystoscopy (see Fig. 6–1). A mid to high lithotomy position provides the best exposure for vulvar and vaginal surgery (Fig. 6–4). Although Allen leg supports are satisfactory for laparoscopic procedures, they are not advantageous or for that matter desirable for most vulvar and vaginal procedures. They may be indicated for radical vulvectomy surgery.

FIGURE 6–1 This patient illustrates the low lithotomy position. Her legs are suspended in candy cane supports.

FIGURE 6–2 This leg support incorporates a gel padding to protect the legs and feet.

FIGURE 6–3 The Trendelenburg (head-down) position adds to the risk of nerve injury when the patient is in the lithotomy position. The inferior extremities are further deprived of blood flow.

FIGURE 6–4 The high lithotomy position requires that the legs are flexed at the knee. Extension at the knee joint adds to the risk of sciatic or lumbosacral trunk injury.

Peripheral Nerve Injury

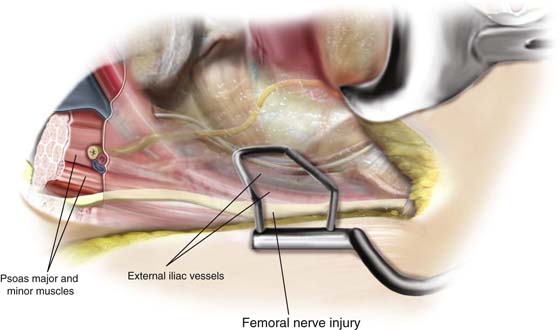

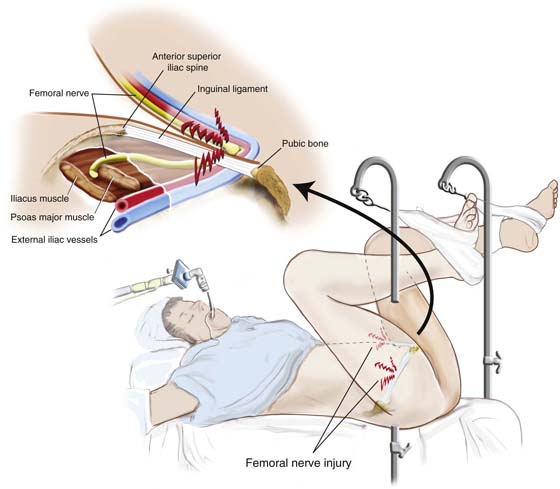

Hyperflexion at the hip will render the patient susceptible to femoral nerve injury (Fig. 6–5). The mechanism of injury relates to the fact that the rigid inguinal ligament compresses the femoral nerve trunk as the latter passes beneath it in its course from the abdomen into the thigh.

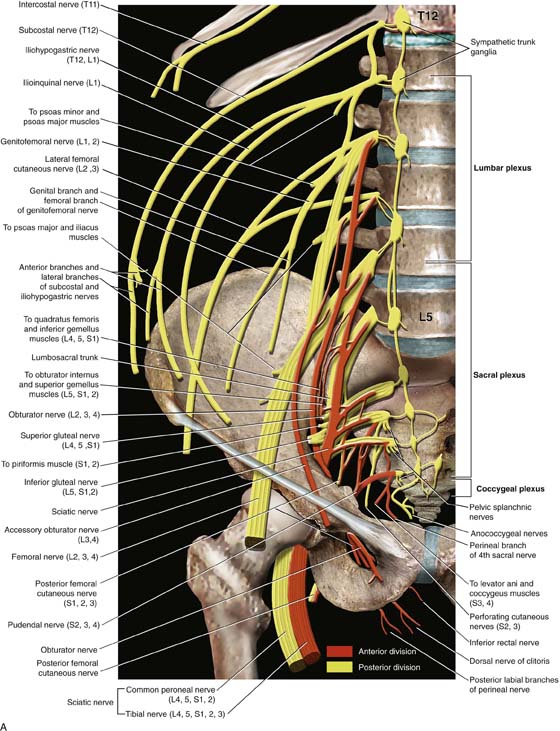

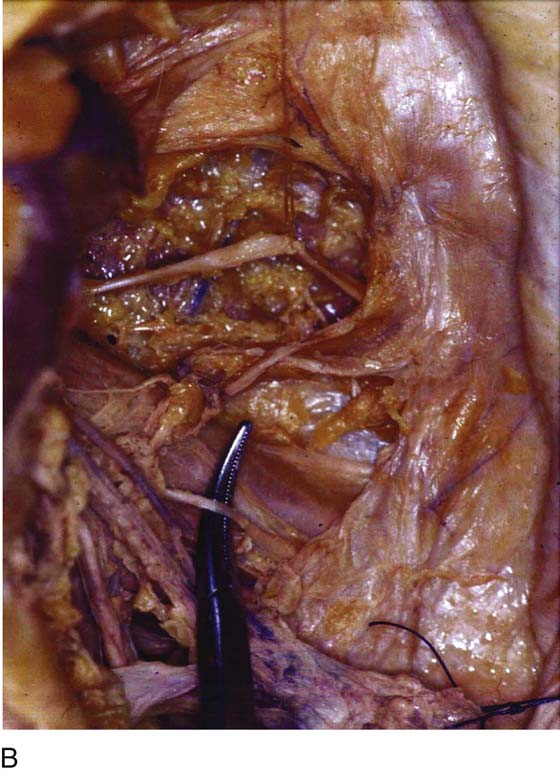

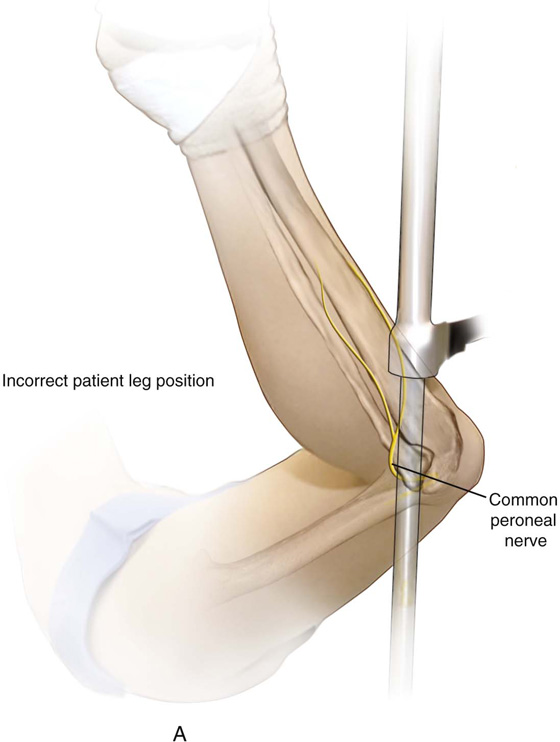

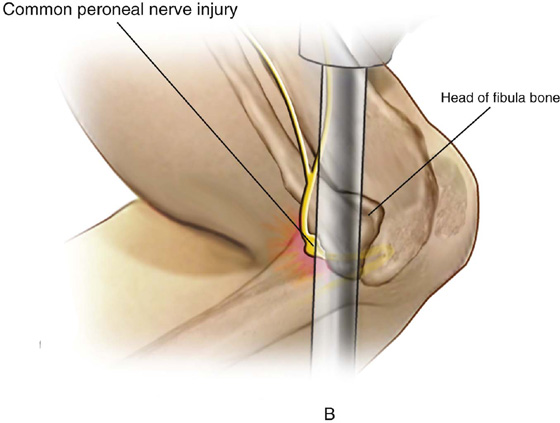

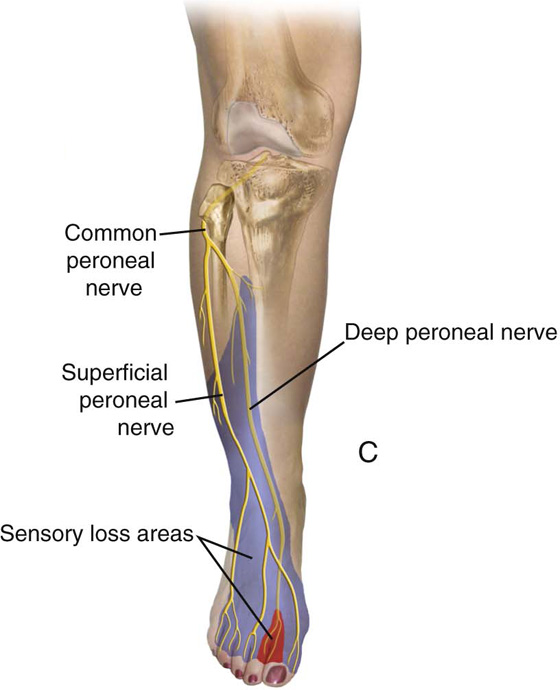

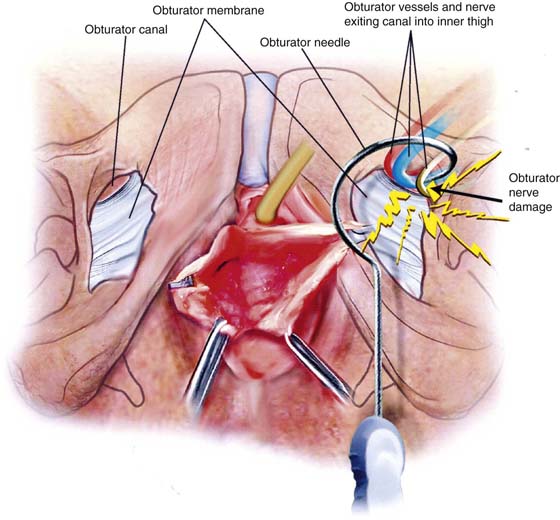

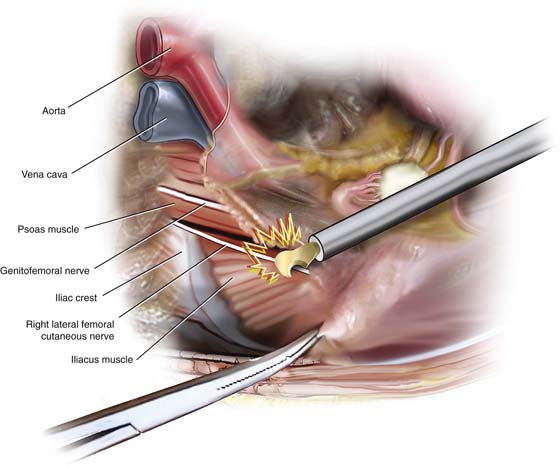

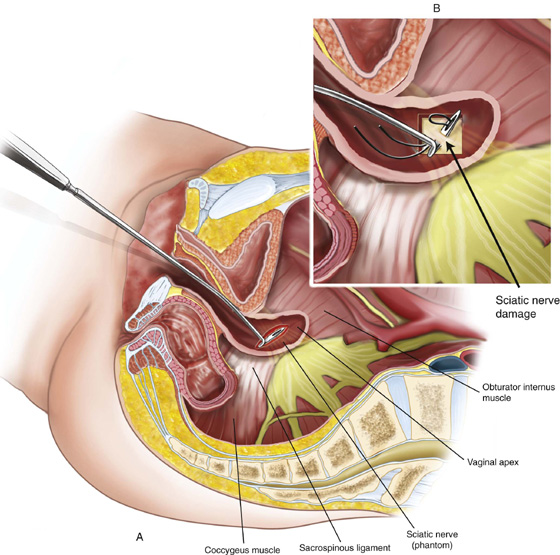

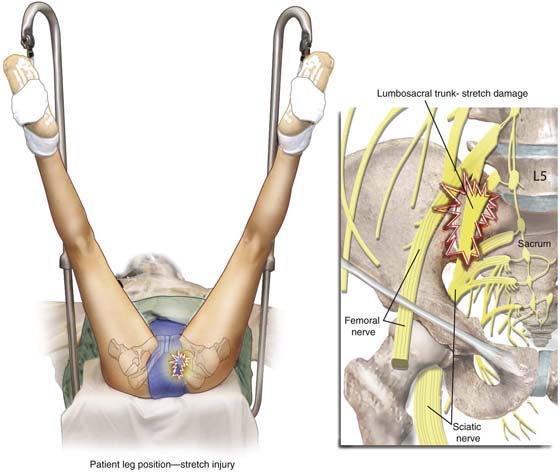

Hyperextension at the knee joint and hip can produce stretch injuries to the lumbosacral trunk and/or sciatic nerve. Short periods of leg extension with the feet in candy cane supports are tolerable, but after 30 minutes, the risk of injury is increased. Excessive abduction (>45°) over 2 hours will endanger the obturator, genital femoral, and/or femoral nerves (Fig. 6–6). The latter nerve is particularly vulnerable when external rotation is added to abduction >45°. Compression at the head of the fibula will injure the peroneal division (Fig. 6–7) of the sciatic nerve, leading to paresis and pain in the leg following distribution of that nerve. Other causes of neuropathies associated with gynecologic surgery in patients who are not in the lithotomy position include self-retaining abdominal retractors, radical surgery, compression related to tight and prolonged packing, hematomas, tumors, and direct injury (e.g., incising the nerve). Figure 6–8A, B shows the key nerves and plexuses that supply innervation to the pelvis and inferior extremities. The relationships of the large nerve roots and trunks to the bony pelvis and to the ligamentous structures are detailed in the drawing. The largest nerves include (1) the sciatic nerve, which lies deep within the pelvis and exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen (the nerve is in close proximity to the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament [Fig. 6–9]); (2) the lumbosacral trunk, which contains elements of the lumbar and sacral plexuses and lies on the sacroiliac joint; and (3) the femoral nerve, which is embedded within the psoas major muscle. The nerve is exposed as it crosses beneath the inguinal ligament and exits via a groove between the iliacus muscle and the psoas major muscle (iliopsoas). After draping, it is wise to change the position of the suspended inferior extremities when surgery extends beyond 2 hours. Additionally, relief of pressure from retractor blades should be carried out every hour or two. Care must be taken with assistants leaning or resting on a patient’s inferior extremities in the lithotomy position (Fig. 6–10). The latter can result in strain on nerves caused by iatrogenically induced excessive abduction and external rotation.

Figures 6–11 through 6–17 illustrate the mechanisms involved in various nerve injuries.

FIGURE 6–5 Hyperflexion at the hip exposes the patient to femoral nerve injury. The point of risk is located beneath the rigid inguinal ligament, where compression of the exposed nerve occurs.

FIGURE 6–6 Extreme abduction combined with external rotation exposes several nerves to the risk of injury, especially with prolonged operative time.

FIGURE 6–7 Lateral pressure at or below the knee will result in compression injury to the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 6–8 A. This schema details the various nerves and their roots of origin, which innervate pelvic and inferior extremity structures. The divisions of the nerve trunks are color-coded and superimposed on an actual pelvis (after Netter). B. Actual dissection shows a tonsil clamp resting on the left psoas major muscle. The nerve that is tented up by the clamp is the genital femoral nerve. Lateral to the psoas major muscle and partially covered with fat is the iliacus muscle. The nerve crossing that muscle is the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

FIGURE 6–9 This dissection follows the posterior division of the left hypogastric artery deep into the pelvis to the level of the ischial spine. The scissors points to the large white nerve trunk of the sciatic nerve. Note the surrounding “wormlike” complex of large venous structures.

FIGURE 6–10 The draped patient in lithotomy position may suffer nerve injury as a result of assistants leaning on the suspended inferior extremities.

FIGURE 6–11 A. The peroneal division of the sciatic nerve is shown lateral to the head of the fibula. B. Close-up shows compression of the nerve between the fibula bone and the metal candy cane stirrup support. C. The neurologic deficit caused by compression injury is shown here.

FIGURE 6–12 A common cause of postoperative femoral neuropathy is abdominal self-retaining retractor compression. Here the retractor blade compresses the psoas major muscle and the femoral nerve, which transmits within the belly of the muscle. Deep blades are particularly prone to cause femoral nerve ischemia, especially when the pressure applied is unrelieved over a long time.

FIGURE 6–13 The lithotomy position associated with hyperflexion at the thigh, especially for operations lasting longer than 2 hours, places the femoral nerve at risk. In the aforesaid circumstances, the femoral nerve is compressed between the inguinal ligament and the pubic ramus. Ischemia is the result of prolonged compression.

FIGURE 6–14 The obturator nerve may sustain injury as it exits the obturator canal and enters the thigh. Here a transobturator needle is shown hooking the neurovascular bundle.

FIGURE 6–15 Energy devices employed for adhesiolysis may cause inadvertent injury to pelvic nerves. This illustration demonstrates a cutting device (harmonic scalpel) incising peritoneal attachments lateral to the psoas major muscle and cutting the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

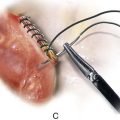

FIGURE 6–16 Transvaginal sacrospinous colpopexy may result in suture injury to the sciatic nerve or to one of the sacral nerve roots. Severe buttock pain and/or foot-drop should alert the gynecologist to rule out sciatic neuropraxia.

FIGURE 6–17 Extended inferior extremities in the lithotomy position can create a stretch injury to the lumbosacral trunk. The patient will exhibit a combination of lumbar and sacral distribution symptoms.

Compartment Syndrome

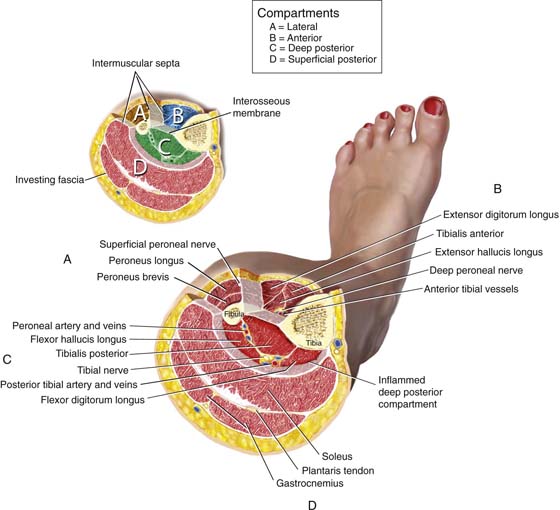

Compartment syndrome affecting the extremities is a particularly disabling condition that occurs when the lithotomy position is combined with leg support, producing calf compression or ankle dorsiflexion. Impaired circulation to the inferior extremities (most frequently caused by hypovolemia and hypotension) is another key instigating factor. The Trendelenburg position creates additive risk for the development of vascular compromise. Postoperative patients who develop inordinate pain, hyperesthesia, and/or paresis in the legs and feet should trigger the gynecologist to include compartment syndrome high up in differential diagnosis considerations. Tense shins and calves are created by increased intracompartmental pressure (Fig. 6–18).

Compartment syndrome may be associated with pelvic vascular injury (e.g., during laparoscopic surgery, following postpartum hemorrhage), traumatic injury (e.g., fracture of leg/thigh bones), hematomas, cellulitis, vascular thrombosis, necrotizing fasciitis, prolonged lithotomy position, and compression stockings. Dorsiflexion at the ankle joint significantly increases compartment pressure.

The pathophysiology of compartment syndrome is related to increasing volume and increasing pressure within unyielding fascial compartments (i.e., limited anatomic spaces). The initiating factor is diminished blood flow to contents within the compartment, thereby creating muscle ischemia. The ischemia in turn increases vascular resistance and further decreases blood flow to the muscles. As a result of continuing ischemia, hemorrhage and edema are additive to intrafascial pressure. The aforesaid happens because of sievelike leakage from venules within the compartment. When the extremities are lowered from lithotomy to supine position, improved flow is established at heart level. The (initiating) hypovolemia, once ameliorated, will result in reperfusion of the extremity. If vascular permeability persists, then further leakage and edema into the fascial space will continue, resulting in still greater intrafascial pressure. Tissue pressure in the compartments ranges on average from 4 to 10 mm Hg but should not exceed 20 mm Hg. Fasciotomy should be performed for pressures of 30 to 40 mm Hg. Neglected compartment syndrome can lead to extensive muscle necrosis, nerve injury, myoglobinemia, cardiac arrhythmia, and myoglobinuric renal damage.

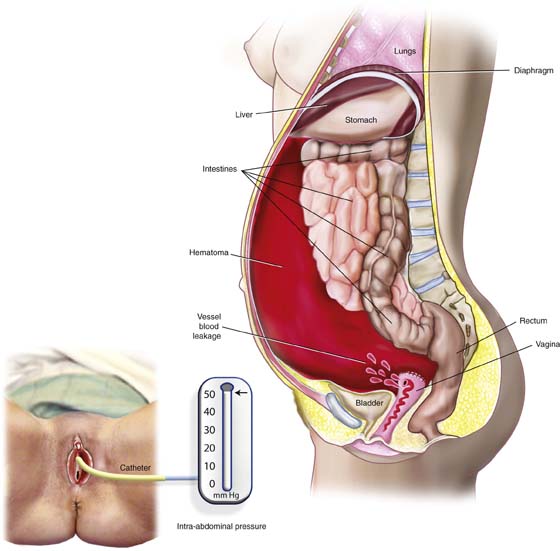

Abdominal compartment syndrome may be defined as a condition that arises from elevated intra-abdominal pressure, leading to visceral injury, as well as to renal, cardiac, and respiratory dysfunction. The abdominal cavity is essentially a closed space, containing viscera and encircled by muscular walls. Acute increases in volume within the abdominal cavity can translate to increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Although normal intra-abdominal pressure ranges from 3 to 10 mm Hg, pressures greater than 25 mm Hg require timely treatment. Gynecologic conditions associated with risk of abdominal compartment syndrome include massive hemorrhage, large hematoma formation, peritonitis and sepsis, intestinal perforation, uterine/ovarian tumors, ascites, and abdominal or tubal pregnancy (Fig. 6–19).

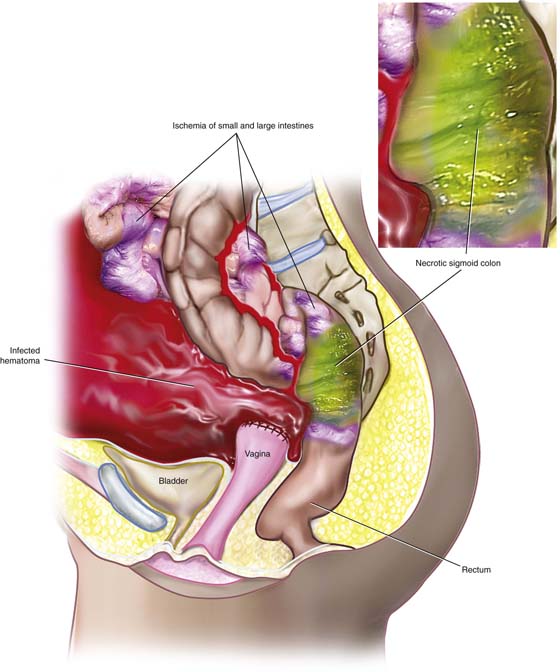

The pathophysiologic ramifications of abdominal compartment syndrome include decreased venous return to the heart with decreased cardiac output, renal dysfunction caused by compression of renal veins, and hepatic abnormality related to pressure on the portal circulation. Intestinal ischemia will eventuate and progress to bowel necrosis because of reduced visceral blood flow and thrombosis (Fig. 6–20). Respiratory function may be compromised as the result of elevation of the diaphragm and transmission of higher intrathoracic pressure, causing reduced lung capacity.

Intra-abdominal pressure may be conveniently measured by placing 100 mL of water into the bladder via a Foley catheter, then connecting the catheter via tubing to a pressure transducer.

The management of abdominal compartment syndrome requires performing laparotomy to reduce pressure and treating the inciting cause(s).

FIGURE 6–18 Cut-away of the leg illustrates the tight fascial compartments bounded by the leg bones and the fascial sheaths. The three compartments are lateral, anterior, and posterior.

FIGURE 6–19 This picture illustrates the formation of a large intra-abdominal hematoma. In this case, the hematoma occurred as the result of a leaking blood vessel, which had not been secured during a hysterectomy. Abdominal compartment syndrome is a possible sequel of the increased intra-abdominal pressure created by the large accumulation of blood within closed space. Intra-abdominal pressure measurements can be obtained by placing a catheter into the bladder and attaching it to a pressure transducer. Pressures greater than 25 mm Hg are diagnostic of significant abdominal compartment syndrome.

FIGURE 6–20 As a result of abdominal compartment syndrome, capillary and small vessel circulation to visceral structures is compromised. This drawing shows the results of prolonged increases in intra-abdominal pressure. The sigmoid colon is necrotic. Additional areas of the small and large intestines show signs of ischemia. The inset details the diffusion of coliform bacteria throughout the necrotic large bowel wall, causing infection of the hematoma.

Nerve Injuries Associated With Positioning and Pelvic Surgery

Nerve Injuries Associated With Positioning and Pelvic Surgery