70. Portal Hypertension

Definition

Portal hypertension is the presence within the portal circulation of a pressure gradient of 12 mm Hg or higher. This malady is associated with numerous conditions as listed in the box below.

Conditions Associated with Portal Hypertension

• Family history of hemochromatosis or Wilson’s disease (see p. 355)

• History of alcohol abuse

• History of blood transfusions and/or intravenous drug use (hepatitis B and/or C)

• History of jaundice

• Pruritus

Incidence

The frequency of occurrence of portal hypertension is not known.

Etiology

Development of portal hypertension can result from many causes, generally classified as prehepatic, intrahepatic (presinusoidal), intrahepatic (sinusoidal and/or postsinusoidal), and posthepatic.

Signs and Symptoms

• Altered sleep patterns

• Ascites

• Asterixis

• Clubbing of digits

• Distended abdominal wall veins (caput medusae)

• Dupuytren’s contracture

• Esophageal varices

• Gynecomastia

• Hematochezia

• Hepatic encephalopathy

• Hepatorenal syndrome

• Increased irritability

• Increasing abdominal girth

• Jaundice

• Lethargy

• Muscle wasting

• Palmar erythema

• Rectal varices

• Spider angiomas

• Splenomegaly

• Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

• Testicular atrophy

|

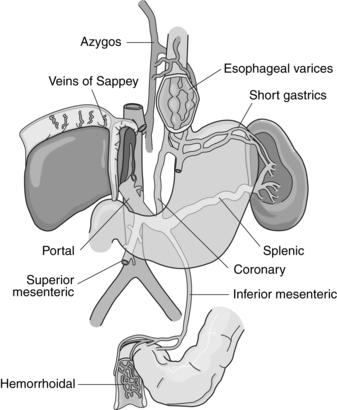

| Portal Hypertension. Varices related to portal hypertension. Portal vein, its major tributaries, and the most important shunts (collateral veins) between the portal and caval systems. |

Causes of Portal Hypertension

Intrahepatic (Presinusoidal)

• Early schistosomiasis

• Hepatic metastasis

• Idiopathic portal hypertension

• Myeloproliferative disease

• Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

• Polycystic disease

• Primary biliary cirrhosis

Intrahepatic (Sinusoidal and/or Postsinusoidal)

• Acute alcoholic hepatitis

• Acute and fulminant hepatitis

• Advanced idiopathic portal hypertension

• Advanced primary biliary cirrhosis

• Advanced schistosomiasis

• Budd-Chiari syndrome (see p. 59)

• Congenital hepatic fibrosis

• Hepatic cirrhosis

• Peliosis hepatis

• Veno-occlusive disease

• Vitamin A toxicity

Posthepatic

• Arterial-portal venous fistula

• Budd-Chiari syndrome (see p. 59)

• Constrictive pericarditis

• Increased portal blood flow

• Increased splenic blood flow

• Inferior vena cava obstruction

• Right-sided heart failure

• Tricuspid regurgitation

Prehepatic

• Congenital atresia

• Portal vein stenosis

• Portal vein thrombosis

• Splanchnic arteriovenous fistula

• Splenic vein thrombosis

Medical Management

Medical care for the patient with portal hypertension is aimed at correcting the underlying cause/disease. Treatment regimens may be categorized as emergent, primary prophylactic, and elective.

Emergent treatment is initiated for the patient presenting with bleeding esophageal varices. Replacement of lost blood volume is the initial treatment measure, with the goal to return the patient’s hematocrit to about a 25% to 30% concentration. Replacement measures must avoid overexpanding the intravascular volume, especially the volume of the varices, to reduce the potential for continued and/or recurrent bleeding.

The source of the bleeding should be determined as quickly as possible.

Pharmacologic treatment may include various compounds, such as vasopressin or octreotide, which act to reduce portal blood flow and/or pressure. Intravenous nitrates are frequently administered in conjunction with vasopressin to significantly improve the latter’s efficacy. Emergent treatment may also include endoscopic sclerotherapy injection, endoscopic variceal ligation, or balloon-tube tamponade (in the event of massive hemorrhage).

Primary prophylaxis is typically employed in a patient considered at high risk for bleeding whether because of severe liver failure, the presence of large varices, or red wale markings on the varices. Prophylactic treatment regimens may entail the administration of β-blocking medications to reduce portal and collateral blood flow. Vasodilators, such as isosorbide mononitrate, may be administered to reduce the high venous pressure gradient and they may reduce esophageal variceal pressure as well.

Sclerotherapy or variceal ligation may be undertaken to prevent hemorrhage. Randomized, controlled clinical trials of sclerotherapy as a primary prophylactic measure have yielded divergent results. As a result, prophylactic sclerotherapy is considered to have no role as a primary prophylactic intervention. Endoscopic ligation has demonstrated greater effectiveness in prevention of initial variceal bleeding. The efficacy demonstrated is similar to results achieved by administration of β-blocking medications.

Surgical interventions are categorized as decompression shunts, devascularization procedures, or liver transplantation. Decompressive shunting is achieved with total portal systemic shunting, partial portal systemic shunting, or other selective shunting, such as the distal splenorenal shunt. Devascularization procedures include splenectomy, gastroesophageal devascularization, or esophageal transection. Liver transplantation is the ultimate procedure to alleviate portal hypertension, recurrent variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and encephalopathy because it fully restores liver function.

Complications

• Ascites

• Bronchial aspiration

• Gastrointestinal varices

• Hepatic encephalopathy

• Hepatorenal syndrome

• Renal failure

• Subacute bacterial peritonitis

• Systemic infection

• Variceal hemorrhage

Anesthesia Implications

Portal hypertension is most commonly a result of significant liver dysfunction, such as cirrhosis or failure. This patient’s clotting ability is questionable at best and should be assessed immediately preoperatively if at all possible. Protein synthesis, specifically production of clotting factors, may be significantly altered by liver dysfunction. Before invasive procedures on the patient with portal hypertension, administration of vitamin K and/or transfusion with fresh frozen plasma may be necessary. If laboratory data indicate the need for these therapeutic measures, they should be administered preoperatively.

Chronic liver failure often incurs chronic steroid adminis-tration. The steroid administration should be maintained on the regular schedule during the perioperative period; the dosage may need to be increased. Administration of histamine (H 2)-antagonists may help reduce the potential for gastro-intestinal bleeding.

Because of the high association of portal hypertension with significant liver dysfunction or failure, drug metabolism will likely be prolonged. Most anesthesia-related drugs, from muscle relaxants to opioids to benzodiazepines to hypnotics, depend on hepatic metabolism for elimination. These medications’ dosages will need to be reduced to lessen the metabolic load on the already dysfunctional liver. Where muscle relaxation is necessary, the more appropriate choice would be atracurium or cis-atracurium. Mivacurium may not be appropriate because of the potentially low pseudocholinesterase concentrations the patient with portal hypertension may have. Due to this same cause, succinylcholine should be avoided as well.