10 Polyuria

Polyuria has been defined variably in the literature. The most commonly used definition is based entirely upon absolute urine volume and arbitrarily defines polyuria as urine volume of more than 3 L/day. However, some authors prefer to define polyuria as “inappropriately high urine volume in relation to the prevailing pathophysiologic state,” regardless of the actual volume of urine.1,2

Classification

Classification

Water Diuresis

Primary Polydipsia

Primary polydipsia can be recognized clinically based on the history of the patient. Usually there is a history of psychiatric illness along with a history of excessive water intake. Many patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses have a moderate to marked increase in water intake (up to 40 L/day).3,4 It is presumed that a central defect in thirst regulation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of primary polydipsia. In some cases, the osmotic threshold for thirst is reduced below the threshold for the release of AVP. The mechanism responsible for abnormal thirst regulation in this setting is unclear. There is evidence that these patients have other defects in central neurohumoral control as well.5 Hyponatremia, when present, also points to the diagnosis of primary polydipsia. The diagnosis of primary polydipsia is usually evident from low urine and plasma osmolalities in the face of polyuria. Hypothalamic diseases such as sarcoidosis, trauma, and certain drugs like phenothiazines can lead to primary polydipsia (Table 10-1). There is no proven specific therapy for psychogenic polydipsia. Free water restriction is the mainstay of therapy.

ATN, acute tubular necrosis; AVP, arginine vasopressin.

Central Diabetes Insipidus

Inadequate secretion of AVP (central diabetes insipidus) can be caused by a large number of disorders that act at one or more of the sites involved in AVP secretion, interfering with the physiologic chain of events that lead to hormone release. However, the most common causes of central diabetes insipidus account for the vast majority of cases. These common causes include neurosurgery, head trauma, brain death, primary or secondary tumors of the hypothalamus, or infiltrative diseases such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis (see Table 10-1).

Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus refers to a decrease in urinary concentrating ability that results from renal resistance to the action of AVP. The collecting duct cells can fail to respond to the actions of AVP. Other factors that can cause renal resistance to AVP are problems that interfere with the renal countercurrent concentrating mechanism, such as medullary injury or decreased sodium chloride reabsorption in the medullary aspect of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. In children, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is usually hereditary. Congenital or hereditary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is an X-linked recessive disorder resulting from mutations in the V2 AVP receptor gene.6 The X-linked inheritance pattern means that males tend to have marked polyuria. Female carriers are usually asymptomatic but occasionally have severe polyuria. In addition, different mutations are associated with different degrees of AVP resistance. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus also can be inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder due to mutations in the aquaporin gene that result in absent or defective water channels, thereby causing resistance to the action of AVP.7

The most common cause of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults is chronic lithium ingestion (see Table 10-1). Polyuria occurs in about 20% to 30% of patients on chronic lithium therapy. The impairment in the nephron’s concentrating ability is thought to be due to decreased density of V2 receptors or to decreased expression of aquaporin-2, a water channel protein. Other secondary causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus include hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, sickle cell disease, and other drugs (see Table 10-1). A water diuresis also can follow relief of obstructive nephropathy. Hypercalcemia-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus occurs when the plasma calcium concentration is persistently above 11 mg/dL (2.75 mmol/L). This defect is generally reversible with correction of hypercalcemia. The mechanism(s) responsible for hypercalcemia-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus remain incompletely understood. Compared to hypercalcemia-induced diabetes insipidus, hypokalemia-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is less severe and often asymptomatic. A rare form of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus can occur during the second half of pregnancy (gestational diabetes insipidus). This condition is thought to be caused by release of a vasopressinase from the placenta, leading to rapid degradation of endogenous or exogenous AVP.8

Approach to Hypotonic Polyuria (Water Diuresis)

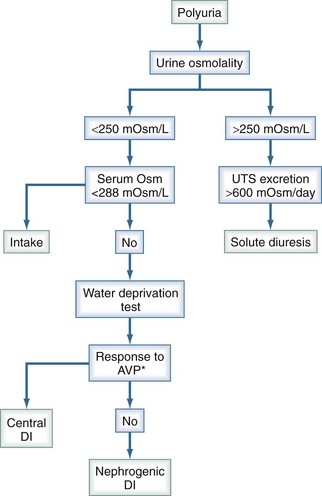

The correct diagnosis is often suggested by the plasma sodium concentration and the history. When the problem is primary polydipsia, the plasma sodium concentration is usually low (dilutional), whereas when the problem is central or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, the plasma sodium concentration typically is normal or high (due to loss of solute free water in excess of solutes). The rate of onset of polyuria can sometimes provide a clue about the diagnosis; when central diabetes insipidus is the problem, the onset of polyuria is generally abrupt, whereas when nephrogenic diabetes insipidus or primary polydipsia is the problem, the onset of polyuria tends to be more gradual. When the diagnosis of central versus nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is unclear, the diagnosis can be confirmed by determining the urinary response to an acute increase in plasma osmolality induced either by water restriction or, less commonly, by administration of hypertonic saline (Figure 10-1).

Comparing urinary osmolality after dehydration with that after vasopressin administration can help differentiate diabetes insipidus due to vasopressin deficiency from other causes of water diuresis (see Figure 10-1). In this test, fluids are withheld long enough to result in stable hourly urinary osmolalities (<30 mmol/kg rise in urine osmolality for 3 consecutive hours). Plasma osmolality and urine osmolality are measured at this time point, then the patient is given 5 units of aqueous vasopressin intravenously (IV). The clinician then measures the osmolality of a urine sample collected during the interval from 30 to 60 minutes after administration of vasopressin. In subjects with normal pituitary function, urinary osmolality does not rise by more than 9% after vasopressin injection. However, in central diabetes insipidus, the increase in urine osmolality after vasopressin administration exceeds 9%. To ensure adequacy of dehydration, plasma osmolality prior to vasopressin administration should be greater than 288 mmol/kg. There is little or no increase in urine osmolality with dehydration in patients with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and there is no further change after vasopressin injection. In the future, a novel method to confirm the results of the water restriction test will be to measure the urinary excretion of aquaporin-2, the collecting tubule water channel that normally fuses with the luminal membrane of the collecting tubule cells under the influence of AVP. In one study, urinary aquaporin-2 excretion increased substantially and to a similar extent after the administration of vasopressin in normal subjects and those with central diabetes insipidus.9 However, in patients with hereditary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, urinary aquaporin-2 excretion was unchanged after vasopressin administration.

Treatment of Water Diuresis

The mainstay of treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is solute restriction and diuretics. Thiazide diuretics in combination with a low-salt diet can diminish the degree of polyuria in patients with persistent and symptomatic nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Thiazide diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide) act by inducing mild volume depletion. Hypovolemia induces an increase in proximal sodium and water reabsorption, thereby diminishing water delivery to the AVP-sensitive sites in the collecting tubules and reducing the urine output. The potassium-sparing diuretic, amiloride, also may be helpful.10

Solute Diuresis

Solute diuresis causing polyuria is due to solute excretion in excess of the usual excretory rate.11 Daily urinary total solute excretion varies widely among different ethnicities, cultures, and dietary habits. The average urinary solute excretion in a healthy American adult is between 500 and 1000 mOsm/d. Solute diuresis can be very severe and can be caused by more than one solute concurrently. Solute diuresis is a relatively common clinical condition and one with important clinical implications. Unless there is adequate replacement of solute and water, a persistent solute diuresis contracts extracellular volume, leading to severe dehydration and hypernatremia. Although glucosuria is the major cause of an osmotic diuresis in outpatients, other conditions are often responsible when polyuria develops in the hospital. These conditions include administration of a high-protein diet, in which case urea acts as the osmotic agent, and volume expansion due to saline loading or the release of bilateral urinary tract obstruction. Multiplying urine osmolality by the 24-hour urine volume gives an estimate of total urine solute concentration. If urinary total solute concentration is abnormally large, a solute diuresis is present.

Solute diuresis can be due to either excessive electrolyte excretion or excessive nonelectrolyte solute excretion. If the total urinary electrolyte excretion exceeds 600 mOsm/d, then an electrolyte diuresis is present. The total urinary electrolyte excretion (in mOsm/d) can be estimated as 2 × (urine [Na+] + urine [K+]) × total urine volume.1,12

An electrolyte diuresis is usually driven by a sodium salt, usually sodium chloride (NaCl).13 Common causes of NaCl-induced diureses are iatrogenic administration of excessive normal saline solution, excessive salt ingestion, and repetitive administration of loop diuretics. Most often, NaCl-induced diuresis is accompanied by water diuresis, causing a mixed solute-water diuresis. Also, more than one electrolyte may be responsible for the diuresis.

A clearly excessive value for urine nonelectrolyte excretion (i.e., >600 mOsm/d) implies that nonelectrolytes are the predominant solutes contributing to the diuresis. The urinary nonelectrolyte excretion can be calculated by subtracting urine electrolyte excretion from the total urine solute excretion. The urine osmolality in these disorders is usually above 300 mOsm/kg; the high osmolality contrasts with the dilute urine typically found with a water diuresis. Furthermore, total solute excretion (calculated as the product of urine osmolality and the urine output over a 24-hour urine collection period) is normal with a water diuresis (600 to 900 mOsm/d) but markedly increased with an osmotic diuresis. The most common nonelectrolyte solute causing excessive diuresis is glucose. Conditions associated with glucose-induced diuresis include diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma.14 Excessive excretion of urea is another important cause of solute diuresis. This problem can occur as a consequence of enteral nutrition using a high-protein tube feeding formula or following relief of urinary tract obstruction or during recovery from acute tubular necrosis.15 Mannitol administration (e.g., as a therapy for intracranial hypertension) also can lead to significant solute diuresis. This issue is pertinent because mannitol is often administered to patients with head trauma, who are at risk for development of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. The correct diagnosis of solute diuresis depends on a clear systematic approach (see Figure 10-1). Management usually involves treatment of the underlying disorder and repletion of extracellular volume by hydration. Since solute diuresis is often accompanied by hypernatremia, and very rapid correction of hypernatremia can have disastrous consequences (e.g., cerebral herniation), it is crucial to carefully monitor serum [Na+]. The serum [Na+] should not be permitted to decrease more than (0.5-1 mEq/L per hour).

1 Kamel KS, Ethier JH, Richardson RM, Bear RA, Halperin ML. Urine electrolytes and osmolality: when and how to use them. Am J Nephrol. 1990;10:89-102.

2 Leung AK, Robson WL, Halperin ML. Polyuria in childhood. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991;30:634-640.

3 Goldman MB, Luchins DJ, Robertson GL. Mechanisms of altered water metabolism in psychotic patients with polydipsia and hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:397-403.

4 Jose CJ, Perez-Cruet J. Incidence and morbidity of self-induced water intoxication in state mental hospital patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:221-222.

5 Goldman MB, Blake L, Marks RC, Hedeker D, Luchins DJ. Association of nonsuppression of cortisol on the DST with primary polydipsia in chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:653-655.

6 Bichet DG, Arthus MF, Lonergan M, Hendy GN, Paradis AJ, Fujiwara TM, et al. X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus mutations in North America and the Hopewell hypothesis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1262-1268.

7 Deen PM, Verdijk MA, Knoers NV, Wieringa B, Monnens LA, van Os CH, et al. Requirement of human renal water channel aquaporin-2 for vasopressin-dependent concentration of urine. Science. 1994;264:92-95.

8 Davison JM, Sheills EA, Philips PR, Barron WM, Lindheimer MD. Metabolic clearance of vasopressin and an analogue resistant to vasopressinase in human pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F348-F353.

9 Kanno K, Sasaki S, Hirata Y, Ishikawa S, Fushimi K, Nakanishi S, et al. Urinary excretion of aquaporin-2 in patients with diabetes insipidus. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1540-1545.

10 Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, Grupp M. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:408-414.

11 Oster JR, Singer I, Thatte L, Grant-Taylor I, Diego JM. The polyuria of solute diuresis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:721-729. (Good overview of solute diuresis)

12 Davids MR, Edoute Y, Halperin ML. The approach to a patient with acute polyuria and hypernatremia: a need for the physiology of McCance at the bedside. Neth J Med. 2001;58:103-110.

13 Narins RG, Riley LJJr. Polyuria: simple and mixed disorders. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;17:237-241. (Good practical review of polyuria)

14 West ML, Marsden PA, Singer GG, Halperin ML. Quantitative analysis of glucose loss during acute therapy for hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. Diabetes Care. 1986;9:465-471.

15 Bishop MC. Diuresis and renal functional recovery in chronic retention. Br J Urol. 1985;57:1-5.