7 Poly-L-lactic acid

Summary and Key Features

• Gradual, subtle, and natural results with a long duration (>2 years) are achievable with poly-l-lactic acid

• As experience has been gained with this product and technical issues have evolved, it has been found to be a safe and effective product with predictable and reproducible results

• Attention to the simple yet critical techniques in the preparation and injection of this biostimulatory agent will minimize adverse events

• Methodology is an important factor in biocompatibility. Remember that the amount of product used at one session is determined solely and completely by the amount of surface area to be treated at that session. The final volumetric correction is determined by the number of treatment sessions

• Experience with facial augmentation has taught us that very empty faces or those with a very elastotic outer skin envelope may be challenging to volumize, requiring a substantial amount of product – any product – to achieve a desirable result. This should be expected in this patient population and discussed prior to any filler treatment to prevent unnecessary frustration for both the patient and the physician

• Thoughtful facial analysis of changes in all structural tissues will enhance site-specific augmentation of volume loss and enhance outcomes

• Patients are starting cosmetic treatments earlier than they have traditionally done. The 2010 American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons statistics revealed that 44% of cosmetic patients are now ‘genXers’ (age 35–50) and 28% are ‘baby boomers’ (51–65). This younger group often needs less product and fewer treatment sessions than the older group and is very gratifying to treat

Poly-L-lactic acid: technical considerations

Methodology is an important determinant of biocompatibility with stimulatory agents. This is outlined below and summarized in Box 7.1.

Even distribution and proper placement of the implanted PLLA is key to a desirable outcome

Even distribution and proper placement of the implanted PLLA is key to a desirable outcome

Proper dilution, reconstitution, and deep placement are critical

Proper dilution, reconstitution, and deep placement are critical

Product must be evenly suspended immediately prior to every injection

Product must be evenly suspended immediately prior to every injection

Immediate post-injection massage

Immediate post-injection massage

Superficial placement leads to visible neocollagenesis

Superficial placement leads to visible neocollagenesis

Placement in active muscles leads to localized overcorrection

Placement in active muscles leads to localized overcorrection

Diffuse papules/nodules likely an issue with reconstitution, i.e. shaking vial immediately after adding water (crystals on sidewalls of vial won’t hydrate), inadequate hydration time, poor suspension immediately prior to injection

Diffuse papules/nodules likely an issue with reconstitution, i.e. shaking vial immediately after adding water (crystals on sidewalls of vial won’t hydrate), inadequate hydration time, poor suspension immediately prior to injection

Focal papules/nodules are likely an issue of placement, i.e. redeposition at the apex of the ‘fan’ when using the fanning technique

Focal papules/nodules are likely an issue of placement, i.e. redeposition at the apex of the ‘fan’ when using the fanning technique

Additional comments

Needle clogging occurs if there is excessive foam in the syringe. This may be cleared by removing the needle, expelling the foam from the syringe, then using a new needle. A small amount of product should then be expelled through the needle prior to injection in the tissue.

Needle clogging occurs if there is excessive foam in the syringe. This may be cleared by removing the needle, expelling the foam from the syringe, then using a new needle. A small amount of product should then be expelled through the needle prior to injection in the tissue.

Deeper injections of fillers may be associated with increased risk of intravascular injections. The low viscosity of this product allows for a reflux maneuver prior to each injection to negate this risk.

Deeper injections of fillers may be associated with increased risk of intravascular injections. The low viscosity of this product allows for a reflux maneuver prior to each injection to negate this risk.

The value of a preceptor experience for the novice injector with PLLA cannot be overemphasized.

The value of a preceptor experience for the novice injector with PLLA cannot be overemphasized.

Prevention and treatment of adverse events

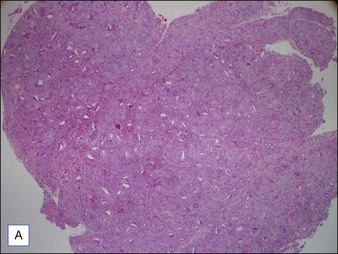

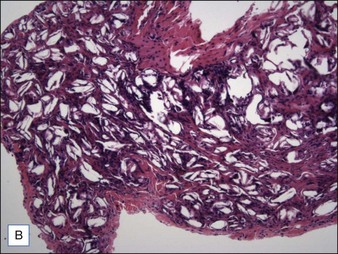

The majority of adverse events are small palpable nodules that stem from suboptimal product reconstitution or placement. Histopathology of nodules shows an overabundance of product with a few foreign-body giant cells, often surrounded by skeletal muscle, as seen in Figure 7.1A. Injection of steroids or antimitotics such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) will have little clinical effect on these lesions as the majority of the lesion is product and not host reaction to product. (Camouflage of these papules with hyaluronic acid gel until they resolve spontaneously may offer more gratifying treatment.) Clinically relevant granulomatous reactions have been reported with all currently available commercial injectable devices. True inflammatory granulomas are unpredictable and rare (the reported rate varies between 0.01% and 0.1%). Histopathology of a lesion such as this will show an overabundance of reaction to product with foreign-body giant cells too numerous to count, as seen in Figure 7.1B. As this is a host response, treatment with intralesional steroids or 5-FU (0.1 mL 40 mg/mL Kenalog® (triamcinolone) mixed with 0.9 mL 5-FU 50 mg/ mL – no more than 2 mL at one session) may be helpful; however, fortunately most resolve spontaneously over time.

Reproduced with permission from Fitzgerald R, Vleggaar D 2011 Facial volume restoration of the aging face with poly-l-lactic acid. Dermatologic Therapy 24:2-27

Patient selection, expectations, and satisfaction

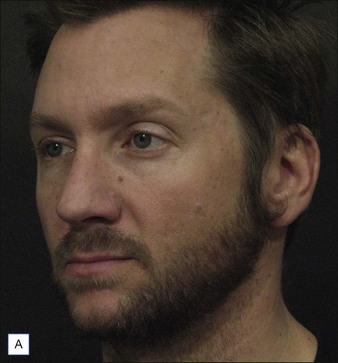

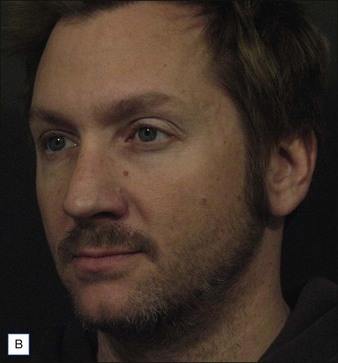

Although our initial experience with PLLA was in the HIV population as well as older cosmetic patients, literature has now been published showing that younger or fuller-faced patients may need less product and fewer sessions, as well as fewer retreatment sessions, than older or very atrophic faces. This is illustrated in the patient cases seen in Figures 7.2–7.5. Treatment of patients needing significant volumization is a gradual, progressive correction carried out through multiple treatment sessions. Patients who are thin, often athletic, with a somewhat skeletal appearance often have the most dramatic improvement. Treatments are usually administered at 1-month intervals (although a longer interval between treatment sessions may be prudent for younger or fuller-faced patients needing less volume). Product placement is briefly outlined in the figure legends. Further detail on this subject may be found elsewhere.

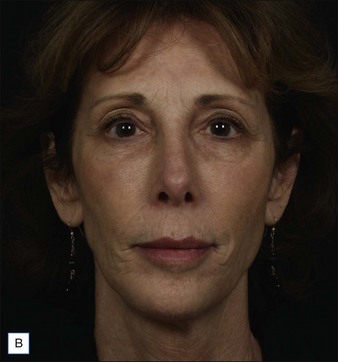

Pathophysiology of the aging face: structural and morphologic

Loss of volume in the bony substructure and fat compartments of the face occurs with age. This is compounded by the loss of elasticity of the skin that envelops it. Change in one area may greatly influence neighboring tissues, leading to a cascade of secondary events. The central role of volume loss and deflation, rather than ptosis, in the aging face has been eloquently illustrated by Lambros. Recognizing where volume is lacking or has been lost in each individual will greatly enhance our ability to address it with site-specific corrections in order to achieve optimal, natural-looking results. Congenital asymmetry in a young patient illustrates some of the clinical effect of the presence or absence of volume in all structural layers and is pictured in Figure 7.6.

Reproduced with permission from Fitzgerald R, Vleggaar D 2011 Facial volume restoration of the aging face with poly-l-lactic acid. Dermatologic Therapy, Vol. 24, 2011, 2-27

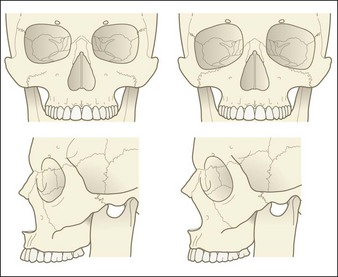

Stuzin has stated that a youthful face represents a point in time when a particular set of skeletal proportions is ideal for their overlying soft tissue envelope. Recent literature does in fact reveal that significant changes do occur in specific regions of the facial skeleton with advancing age, and that these morphologic changes in bony structures affect soft tissue position. Much of this literature has been summarized in an excellent recent review by Sharabi et al. The most significant changes have been documented in the glabellar, orbital, maxillary, and pyriform angles, as well as in the height and width of the orbital aperature and pyriform aperature, and are illustrated in Figure 7.7. This work supports the ‘concertina’ effect concept presented by Pessa over a decade ago stating that deficient bony support may account for soft tissue bundling seen in both infancy and advancing age, i.e. that ideal proportions may be a place we grow into from infancy and away from with age. The clinical value of this work lies in its implications for craniofacial augmentation by solid implants, or by injectable agents, resulting in the restoration of tissue support and a reversal, to some degree, of the ‘concertina’ effect.

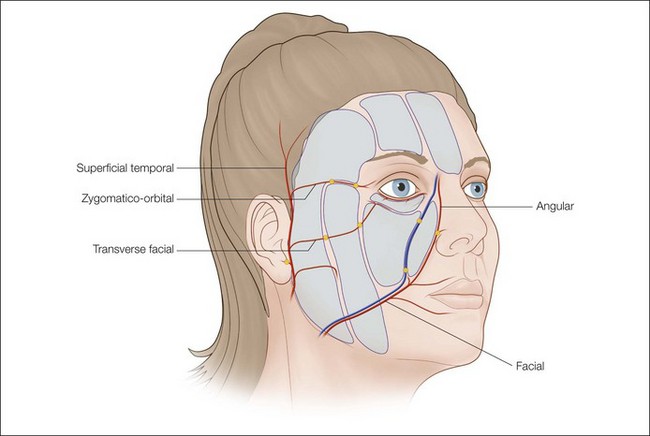

Rohrich & Pessa have performed multiple cadaver studies showing that subcutaneous fat is compartmentalized, specifically by fascial extensions that travel from superficial fascia to dermis (which dictate the location and shape of each compartment). These fascial extensions form a framework that provides a ‘retaining system’ for the human face as well as a conduit for blood vessels and are depicted in Figure 7.8. Superficial compartments are supported by deep fat compartmentalized in a similar fashion. Implicit in this concept is the suggestion that the face ages three-dimensionally, with separate compartments changing relative to one another by both position and volume. Volume loss of specific fat compartments leads to loss of anterior projection (deep fat) and predictable changes in the topography of the face (superficial and deep fat). Understanding the anatomy of all of these areas lends greater precision to our ability to rejuvenate the aging face.

Butterwick K, Lowe NJ. Injectable poly-L-lactic acid for cosmetic enhancement: learning from the European experience. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009;61:281–293.

Fitzgerald R, Vleggaar D. Facial volume restoration of the aging face with poly-l-lactic acid. Dermatologic Therapy. 2011;24:2–27.

Lambros V. Observations on periorbital and midfacial aging. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;120:1367–1376.

Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers. Part 2. Treatment options. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;123(6):1864–1873.

Levy RM, Redbord KP, Hanke CW. Treatment of HIV lipoatrophy and lipoatrophy of aging with poly-l-lactic acid: a prospective 3 year follow up study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;59(6):923–933.

Lowe P, Lowe NJ, Patnaik R. Three-dimensional digital surface imaging measurement of the volumizing effect of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for nasolabial folds. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2011;13(2):87–94.

Mandy SH. Fillers that work by fibroplasia – poly-l-lactic acid. In: Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Soft tissue augmentation. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008:101–104.

Narins RS, Baumann L, Brandt FS. A randomized study of the efficacy and safety of injectable poly-L-lactic acid versus human-based collagen implant in the treatment of nasolabial fold wrinkles. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010;62(3):448–462.

Palm M, Goldman M. Patient satisfaction and the duration of effect with PLLA: a review of the literature. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2009;10:S15–S20.

Pessa JE, Zadoo VP, Yuan C, et al. Concertina effect and facial aging: nonlinear aspects of youthfulness and skeletal remodeling, and why, perhaps, infants have jowls. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1999;103:635–644.

Rohrich R, Pessa J. Discussion: aging of the facial skeleton: aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;127(1):384–385. discussion

Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE, Ristow B. The youthful cheek and the deep medical fat compartment. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(6):2107–2112.

Sharabi SE, Hatef DA, Koshy JC, et al. Mechanotransduction: the missing link in the facial aging puzzle? Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2010;34(5):603–611.

Shaw R, Katzel E, Koltz P, et al. Aging of the facial skeleton: aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127:374.

Stuzin J. Restoring facial shape in face lifting: the role of skeletal support in facial analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;119(1):362–376.