Nurses are playing a major role in the political process for planning the future of health care.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define politics and political involvement.

• State the rationale for a nurse to become involved in the political process.

• List specific strategies needed to begin to affect the laws that govern the practice of nursing and the health care system.

• Discuss different types of power and how each is obtained.

• Describe the function of a political action committee.

• Discuss selected issues affecting nursing: multistate licensure, nursing and collective bargaining, and equal pay for work of comparable value.

Too often nurses feel that the legislative process is associated with wheeling and dealing, smoke-filled rooms, and the exchange of money, favors, and influence. Many believe politics to be a world that excludes people with ethics and sincerity—especially given the controversies in presidential administrations and political party ideologies that so often result in gridlock. Others think only the wealthy, ruthless, or very brave play the game of politics. It seems that most nurses feel that the messy business of politicking should be left to others while they (nurses) do what they do best and enjoy most: taking care of patients.

Today, however, nurses are coming to realize that politics is not a one-dimensional arena but a complex struggle with strict rules and serious outcomes. In a typical modern-day political struggle, a rural health care center may be pitted for funding against a major interstate highway. Certainly, both projects have merit, but in times of limited resources not everyone can be victorious. Nurses are now aware that to influence the development of public policy in ways that affect how we are able to deliver care, we must be engaged in the political process.

Leavitt and colleagues (2002) wrote that “the future of nursing and health care may well depend on nurses’ skills in moving a vision. Without a vision, politics becomes an end in itself—a game that is often corrupt and empty” (p. 86). To demonstrate these skills, nurses must elect the decision makers, testify before legislative committee hearings, compromise, and get themselves elected to decision-making positions. Nurses realize that involvement in the political process is a vital tool that they must learn to use if they are to carry out their mission (providing quality patient care) with maximum impact.

Nurses’ recognition of problems in the current health care system, and their commitment to the principle that health care is a right of all citizens, fuel their desire to become active in the political arena and to form a collective force to improve the health care system.

An example of the power of the nursing collective is evidenced in organized nursing’s efforts to provide support and defense for a Texas nurse who was discharged from her hospital position for reporting a physician to the Texas Medical Board for medical patient care that the nurse believed was unsafe (ANA, 2010). The nurse, a member of the Texas Nurses Association and the American Nurses Association, also faced a third-degree felony charge for “misuse of official information.”

The Texas Nurses Association became aware of the case and immediately offered to support the nurse involved in the case and enlisted the support from the ANA as well. The call went out from the ANA to all nurses, and more than $45,000 was donated both by individuals and organizations from across the United States to support the defense of this nurse. ANA and the Texas Nurses Association strongly criticized the criminal charges and the fact that this case could have a long-term negative impact on nurses who are acting as whistle-blowers advocating for their patients.

The case went to trial, and a jury found the nurse not guilty. The ANA President at the time, Rebecca M. Patton, RN, MSN, CNOR, said of the outcome, “ANA is relieved and satisfied that Anne Mitchell (RN) was vindicated and found not guilty on these outrageous criminal charges—today’s verdict is a resounding win on behalf of patient safety in the U.S. Nurses play a critical, duty-bound role in acting as patient safety watch guards in our nation’s health care system. The message the jury sent is clear: the freedom for nurses to report a physician’s unsafe medical practices is nonnegotiable. However, ANA remains shocked and deeply disappointed that this sort of blatant retaliation was allowed to take place and reach the trial stage—a different outcome could have endangered patient safety across the U.S., having a potential chilling effect that would make nurses think twice before reporting shoddy medical practice. Nurse whistle-blowers should never be fired and criminally charged for reporting questionable medical care” (ANA, 2010, para 5).

It is important for nurses to join and to support nursing organizations that advocate and lobby on behalf of nurses, nursing, and quality health care. Not all nursing organizations have a governmental affairs division for lobbying. The American Nurses Association has lobbyists in Washington, DC, to advocate for the concerns of the profession. In addition, most of the constituent state nurses associations have legislative activities at the state level. (Several nursing associations, including the ANA, are described in Chapter 9.) Before joining a nursing association, you should ask whether the association lobbies on behalf of the interests of its members. The future power of nurses depends on nurses joining and supporting such associations.

The nursing profession will also continue to work with the national media to portray nurses in a positive, professional light. For nurses to be effective in promoting policy, the public needs a clear picture of what nurses bring to the American health care delivery system. For example, ANA responded to an event dealing with a nurse who was competing in the Miss America contest and who was delivering a dramatic monologue about her experience as a nurse. A co-host of the television program “The View” mocked the monologue and the nurse for wearing a “doctor’s stethoscope,” as if the nurse were wearing a costume.

ANA led a national outcry over this situation with the message “nurses don’t wear costumes; they save lives.” As a result, there was so much public and advertiser backlash over this comment that the network, the television program, and the co-host issued an apology (ANA, 2015a).

What Exactly is Politics?

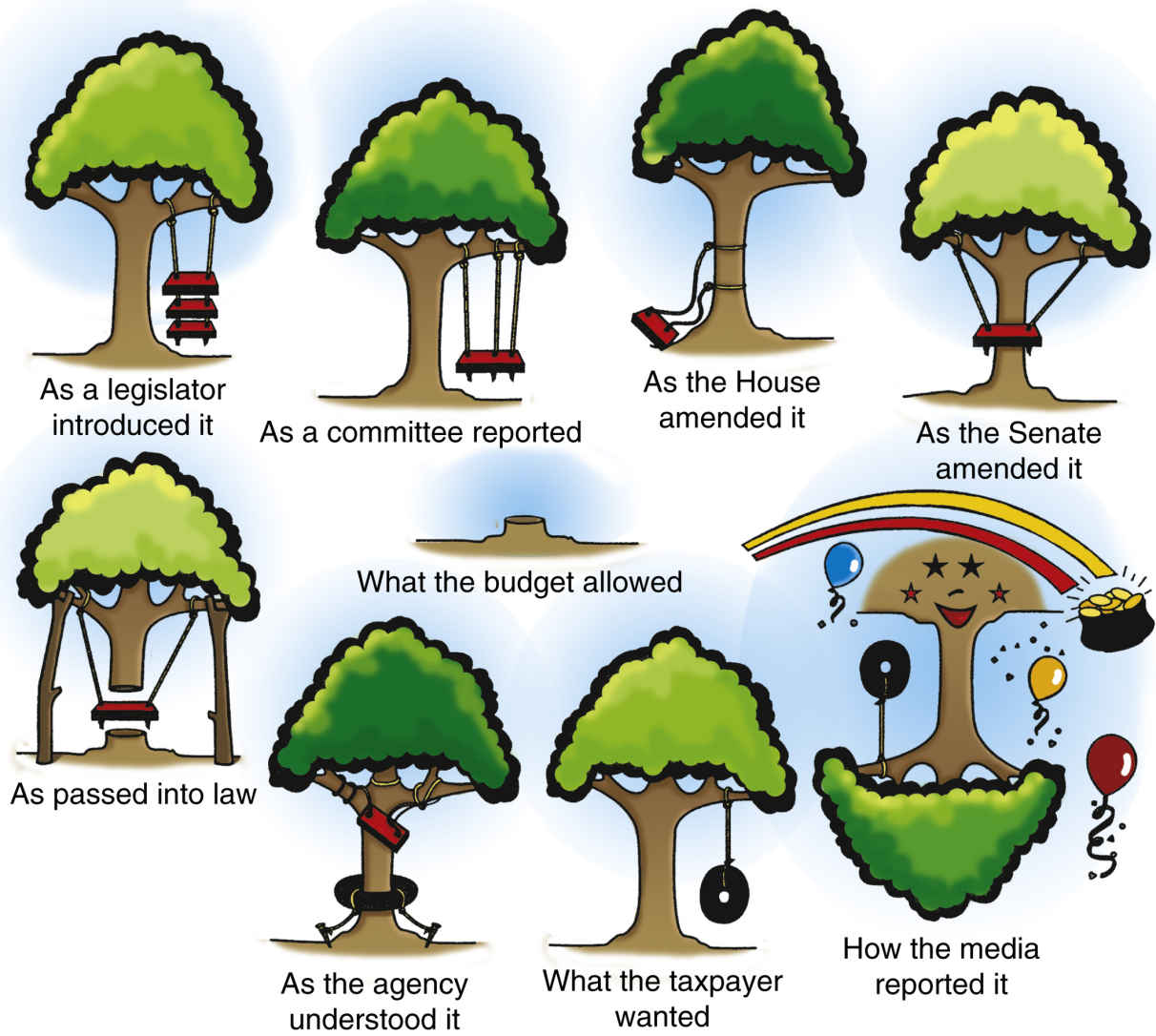

Politics, described by (Mason et al., 2007, p. 4), is a vital tool that enables the nurse to “nurse smarter.” Involvement in the political process offers an individual nurse a tool that augments his or her power, or clout, to improve the care provided to patients. Whether on the community, hospital, or nursing-unit level, political skills and the understanding of how laws are enacted enable the nurse to identify needed resources, gain access to those resources, work with legislative bodies to lobby for changes in the health care system, and overcome obstacles, thus facilitating the movement of the patient to higher levels of health or function (Fig. 17.1).

Let us look first at the nursing-unit level:

Your hospital is in the process of selecting a new supplier of IV pumps. You and the other nurses on your unit want to have input into that decision, because IV pumps are essential to the care of your patients, and you have a definite opinion about the type of IV pump that works best. But the intensive care unit nurses, who are thought to be more important and valuable because the nursing shortage has made them as rare as hen’s teeth, have the only nurse position on the review committee (and therefore, the director’s ear!). You and the nurses on your unit strategize to secure input into this important decision.

Your plan might look like this:

▪ Gather data about IV pumps—cost, suppliers, possible substitutes, and so on.

▪ Communicate to the charge nurse and supervisor your concern about this issue and your plans to become involved in the decision (by using appropriate channels of communication).

▪ State clearly what you want—perhaps request a seat on the committee when the opportunity arises.

▪ Summarize in writing your request and the rationale, submitting it to the appropriate people.

▪ Establish a coalition with the intensive care unit nurses and other concerned individuals.

▪ Become involved with other hospital issues, and contribute in a credible fashion (i.e., do not be a single-issue person).

What Other Strategies Would You Suggest?

The scenario described here illustrates what a politically astute nurse would do in this situation. Although the example applies to a hospital setting, the strategies are comparable to those necessary for becoming involved on a community, state, or even federal level. Practicing at the local level will provide good experience for larger issues—one has to start somewhere. Furthermore, a nurse involved on the local level will be able to hone her or his skills, thus gaining confidence in the ability to handle similar “exercises” in larger forums.

In the previous example, the nurse was able to formulate several “political” actions to influence the outcome of the IV pump decision (Critical Thinking Box 17.1).

What Are the Skills That Make Up a Nurse’s Political Savvy?

Ability to Analyze an Issue (Those Assessment Skills Again!)

The individual who expects to “influence the allocation of scarce resources” must do the homework necessary to be well informed. She or he must know all the facts relevant to the issue, how the issue looks from all angles, and how it fits into the larger picture.

Ability to Present a Possible Resolution in Clear and Concise Terms

Ability to Participate in a Constructive Way

Too often, a person disagrees with a proposal being suggested to a hospital unit (or city council) but only gripes about it. The displeased individual seldom takes the time to study the problem or to understand its connection with other hospital departments (or city programs in a broader issue). Most important, the displeased person seldom suggests an alternate solution.

In short, if an individual’s concern is not directed toward solving the problem, that person will not be seen as a team player but as a troublemaker. Constructive responses, perhaps something as simple as posing a single question such as “What solution would you suggest?” may help those involved think in positive terms and redirect energy to a more productive mode. Positive action can produce the kind of creative brainstorming that results in a solution.

Ability to Voice One’s Opinion (Understand the System)

After the homework is done, let the right person know the opinion or solution that has been determined. For example, the nurse might communicate concern and knowledge about the issue to the nurse manager and supervisor. It is important, of course, to make an intelligent and well-informed decision about the person to whom it is best to voice one’s opinion.

Having a confidant or mentor who knows the environment is one way to acquire this information, as he or she can provide you with insight regarding the appropriate person to whom you can express your opinion and suggestions. Another strategy is to use your listening skills. Simply standing back and listening are assets that will come in handy! Whatever the technique, studying the dynamics of the organization with all senses will help the nurse decide on the best person and the most appropriate way to communicate the proposed solution.

Ability to Analyze and Use Power Bases

While discussing issues with colleagues and studying the organization, be alert to the various power brokers. In the previous IV pump vignette, the nurse notes the VP of Purchasing is an obvious source of power in the hospital. This VP will certainly concur with, if not make, the final decision. However, be aware that power does not always follow the lines on the organizational chart. The power of the nurse aide on the oncology unit who just happens to be the niece of the newly appointed member of the Board of Trustees may escape the notice of some. This person could be used to influence a decision if necessary. Similarly, the fact that the VP of Purchasing’s mother was on the unit should be filed in your memory for future use.

Understanding policy that has been promulgated by respected bodies can also be used as a power base. For example, the Institute of Medicine issued a report in 2011 called The Future of Nursing. One of the major tenets of this respected report is that nurses should be able to practice to the full extent of their education, licensure, and training (IOM, 2011).

If a school nurse is trying to make a point about staffing in schools or about the expanded role of the school nurse, using such information can reinforce the power behind the message (Fleming, 2012). On a more global level, using such a power base can help to make the point that the expansion of the role of advanced practice nurses can help to alleviate the massive shortage of primary care physicians and can improve care processes (Newhouse et al., 2012).

Facts may be facts, but where one gets information can sometimes make a statement as powerful as the information itself. Having the ability to use many different channels of information will afford the nurse the power to choose among them.

What is Power, and Where does it Come from?

Sanford (1979) describes five laws of power. She recommends that these laws be studied to identify strategies to develop power in nursing. The laws are as follows:

Law 1: Power Invariably Fills Any Vacuum

When a problem or issue arises, the prevailing desire is for peace and order. People are willing to yield power to someone interested in restoring order to situations of discomfort. Therefore someone will eventually step forward to handle the dilemma. It may be some time before the discomfort or unrest grows to heights sufficient for someone to take the lead.

Nonetheless, a person exerting power will step forward to offer a solution. In some situations, this person may be the previously identified leader, the nurse manager, or the department chair. More often there is an official power broker influencing the action. Know that there are opportunities to exert influence—for example, by taking the leadership role (i.e., stepping forward to fill the vacuum).

Law 2: Power Is Invariably Personal

In most instances, programs are attributed to an organization. For example, the state and national children’s and health associations proposed a fictitious program called ImmunEYEs. If one investigated, however, it might be found that the program began with a small group of friends talking while eating a pizza one evening, lamenting the number of infants still not immunized. In the course of their conversation, one might have said, “If we were to create a media blitz that would get the need for immunizations into the consciousness of parents—get the need for immunizations in their face!” And the next person might have said, “In their eyes! Yea, ImmunEYEs. Let’s do it!”

Initiatives such as this start with one person creating a new approach to a problem. That person exercises power by providing the leadership or spark to create the strategy to carry out such an initiative, thus inspiring and motivating people to contribute to the effort.

Law 3: Power Is Based on a System of Ideas and Philosophy

Behaviors demonstrated by an individual as she or he exerts power reflect a personal belief system or a philosophy of life. That philosophy or ideal must be one that attracts followers, gains their respect, and rallies them to join the effort. Nurses have the opportunity to ensure that a patient’s right (versus privilege) to health care, access to preventive care, and similar values are reflected in policies and procedures.

Law 4: Power Is Exercised Through and Depends on Institutions

As an individual, one can easily feel powerless and unable to handle the complex problems facing a hospital, community, or state. But through a nursing service organization, a state nurses association, or a similar organization, that individual can garner the resources needed to magnify her or his power. The person-to-person network, the communication vehicle (usually an organization’s newsletter or journal), and the organizational structure are established for precisely this function—to support and foster changes in the health care system.

Law 5: Power Is Invariably Confronted With and Acts in the Presence of a Field of Responsibility

Actions taken create a ripple effect by speaking to the other nurses for whom nurses act and, most important, the patients for whom nurses advocate. The individual in the power position is acting on behalf of the group. Power is communicated to observers and is reinforced by positive responses. If the group thinks that its ideals are not being honored, the vacuum will be filled with the next candidate capable of the role and supported by the organization.

Another Way to Look at Power and Where to Get It

In a classic, much-referenced work, French and Raven (1959) describe five sources of power. They are (in order of importance) reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, referent or mentor power, and expert or informational power. These descriptions of power were presented in the discussion of nursing management in Chapter 10. The discussion there described the use of power within the ranks of nursing. Here, the use of power is presented as it applies to the political process, especially through political action in nursing.

The strongest source of power is the ability to reward. The best example of making use of the reward power base is the giving of money. If, for example, someone gives a decision maker financial support for a future political campaign, the recipient will feel obligated to the donor and may, from time to time, “adjust opinions” to repay these obligations! Today, because caps have been placed on campaign contributions, the misuse of this type of reward has been reduced.

An additional source of reward-based political power is the ability to commit voters to a candidate through endorsements. This illustrates the importance of having a large number of members in an organization—in other words, a large voting bloc. This reinforces the imperative for nurses to join and support nursing organizations that advocate on behalf of nurses, nursing, and quality health care.

Second in importance is the power to coerce or “punish” a decision maker for going against the wishes of an organization. The best example of this power, the opposite of reward, is the ability to remove the person from office at election time.

Third in importance is legitimate power, or the influence that comes with role and position. Influence derives from the status that society assigns individuals as a result of, for instance, inherited family money, membership in a respected profession, or a prominent position in the community. The dean in a school of nursing has a certain amount of influence just because of who he or she is. Right? A nurse’s commitment to enhancing nursing’s influence explains why nurses encourage and assist one another to achieve key decision-making positions—to build nursing’s legitimate power base.

The fourth power base is that of referent or mentor power. This is the power that “rubs off ” of influential people. When representatives of the student body talk with a faculty member about a problem they are having with a course, and they receive her or his support, the curriculum committee or dean is more likely to listen sympathetically than if the students were arguing only for themselves. The faculty member, joining with the students to solve their problem, adds to the students’ power. The wish to build this type of power encourages nurses to join coalitions, especially those including organizations with greater power than their own.

The last and weakest of the power bases is that of expert or informational power. Nurses know about health and nursing care and are thus able to impart knowledge in this area with great confidence and style. Typically, nurses communicate this authority through letters written to legislators, testimonies presented in hearings, and through other contacts made on behalf of nursing and patients. In summary, power is derived from various sources. Nurses use, with the greatest frequency and ease, the weakest of the power bases—that deriving from their expertise. Although this is an important power base, nurses must develop and exercise the other types as well. Only then will nurses realize the full extent of their potential (Critical Thinking Box 17.2).

Networking Among Colleagues

It has been said that one should never be more than two telephone calls away from a needed resource, whether it be a piece of information, a contact in a hospital in another city, or input into a decision one is about to make. The key to successful networking is consciously building and nurturing a pool of associates whose skills and connections augment your own.

As a nursing graduate, one should begin the important task of networking by selecting an instructor from nursing school who is able to speak positively about your performance during nursing school. Ask this person if she or he would be willing to write a letter of reference for your first job. If the person agrees, nurture this contact from that time onward. Keep this individual apprised of your whereabouts, your successes, and your plans for the future. This person will be an important link not only to your school but also to your future educational and career undertakings. Then, at each future work site, find a charge nurse or supervisor willing to write a reference and with whom you can maintain contact. Keep building the network throughout your career.

Remember that this network must be nourished. Constant use of one’s resources without reciprocation will exhaust them and make them unreliable sources of assistance in the future. But if properly cared for, this network will provide support for the rest of your career.

Building Coalitions

A coalition is a group of individuals or organizations who share a common interest in a single issue. Groups with whom nurses might form coalitions are as diverse as the topics about which nurses are concerned. For example, nurses are concerned about and lobby for adequate, safe child care, a safe environment, and women’s issues. The numerous organizations interested in these diverse issues are potential candidates for a coalition with nursing organizations. It is not unusual, however, for two organizations to be in a coalition on one issue but adversaries on another. Indeed, this is common in the political arena, where negotiations and compromises are the norm.

A warning: the selection of coalition partners should strengthen your cause or organization. Forming coalitions is a strategy to empower oneself. Therefore, build coalitions with people more powerful than you, and build coalitions with organizations enjoying greater power than nursing, not less (Critical Thinking Box 17.3 and Fig. 17.2).

What About Trade-Offs, Compromises, Negotiations, and Other Tricks of the Trade?

Politics is not a perfect art or science. In the heat of battle, nurses are often called on to compromise, but if they are unwilling to bend on some principle, they sacrifice all. To hold out for the ideal typically means that no progress toward the ideal will be realized. Often, changes in health care policies are achieved in incremental steps. However, the decision to compromise a value or principle must be carefully made with full realization of the implications—not an easy decision!

The political skills discussed so far apply to any situation, whether in a family, a hospital unit, or a community. The next part of the chapter is focused on skills that apply specifically to the governmental process.

How Do I Go About Participating in the Election Process?

One key to successful political activity is involvement in the election process. This is the stage where one can get to know the candidates; they also get to know you. In addition, it is a time when one makes important contacts for that network.

Getting involved in a candidate’s campaign is simple. First, study the positions to be filled. Then, with the help of the local nurses’ association, the local newspaper, or the county or state Democratic or Republican Party, select the candidate whose views on health care most closely match yours. Next, find the candidate’s campaign headquarters. After this, contact the candidate’s volunteer coordinator to see when volunteer help is needed. Most campaigns are crying for assistance with folding letters and stuffing envelopes, looking up addresses, and preparing bulk mailings. They will welcome you with great enthusiasm! Be sure to tell the campaign staff that you are a nurse and would be more than willing to contribute to the candidate’s understanding of health care issues and to assist in drafting the candidate’s positions on these issues (Critical Thinking Box 17.4).

Beware: Involvement in campaigns and party organizations can lead to catching the political “bug.” Victims of the political bug are overcome by a powerful desire to make changes in the system, and they see a multitude of opportunities to educate people about the health needs of a county, state, and nation. An example of two nurses who caught the bug: During a past national presidential election, the nurses at a state caucus volunteered to write the resolution for the party’s position on health care, which, if passed, would become a plank in the platform. After much work drafting the statement and bringing it before various committees, they were ecstatic when it passed and became the health statement for their party! (Review the case studies in the Evolve Resources for an example of the effectiveness of political action by nurses.)

What Is a Political Action Committee?

Another way that nurses can influence the elective process is through involvement in an organization’s political action committee. Political action committees, or PACs, grew out of the Nixon/Watergate era, when Congress decided that candidates for public office were becoming too dependent on money supplied by special interests—individuals who give large political contributions and thereby exert undue influence over the elected official’s decisions.

As a result, Congress limited the amount of money an individual may contribute to a candidate, established strict reporting requirements, and created a mechanism whereby individuals can pool their resources and collectively support a candidate.

The ANA National Political Action Committee is called ANA-PAC. Through this vehicle, nurses across the country organize to collectively endorse and support candidates for national offices. Likewise, state nurses associations have state-level PACs to influence statewide elections. There may be PACs in your area that endorse candidates in city elections. All PACs must comply with the state or federal election codes and report financial support given to candidates for public office.

Today, PACs play an important role in the political process, because they provide a mechanism whereby small contributors can act as a collective, participating in the electoral process when otherwise they would feel outmaneuvered by the bigger players.

The ANA’s Endorsement Handbook stresses four points regarding PACs:

1. Political focus. The only purpose of any PAC is to endorse candidates for public office and then supply them with the political and financial support they need to win an election.

2. No legislative activities. A PAC does not lobby elected officials; that is the job of the ANA or the state nurses association and its government-relations arm. A PAC simply provides financial and campaign support for candidates whose views are generally consistent with those of its contributors.

3. Not “dirty.” A PAC does not “buy” a candidate or a vote. However, the very nature of political life suggests that candidates who recognize an organization’s ability to affect their electoral prospects will be inclined to listen to the group’s views when considering specific pieces of legislation.

4. Health concerns only. Nursing PACs evaluate the candidates on nursing and health concerns only. In other words, ANA-PAC might solicit the candidates’ ideas about how Congress might address the problem of older adult abuse in long-term care facilities or expanding health care insurance coverage for the uninsured. But the organization as a nursing PAC should not include questions, for instance, about the source of funding for the new cabinet on foreign commerce. The organization speaks for members only on issues covered in its philosophical statements, resolutions, position statements, legislative platforms, or other documents that its members as an organization have accepted (Critical Thinking Box 17.5).

After Getting Them Elected, Then What?

Lobbying is the attempt to influence or sway a public official to take a desired action. Lobbying is also characterized as the education of the legislator about nursing and its issues. Educating officials, like educating patients, is an important part of the nurse’s role.

As nurses, we can lobby in several different ways. The first and best opportunity to lobby comes when the nurse first meets the candidate and evaluates her or him as a potential officeholder. This is the time to assess the candidate’s knowledge of health care issues. Take the time to teach and to learn.

A second opportunity comes when the official needs information to decide how to vote on an issue. Depending on time constraints, the issue, and other considerations, a nurse might decide to lobby the official in person or in writing. If time and financial resources permit, the most powerful type of contact is a face-to-face visit. The only way to ensure time with your senator or representative is to make an appointment. Even then, you may not be successful.

If you are making an unscheduled visit to the Capitol that precludes an appointment, the best time to catch your senator or representative is early in the day, before the legislative sessions or committee meetings start; they rarely start before 10 or 11 AM. Contact with the legislator’s aid or assistant can be just as effective as time spent with the official. Busy federal and state officials depend heavily on their staff. Treat staff members with the respect they deserve! Be sure to leave a business card or your name and contact information in writing, including an e-mail address. Make sure that they know how to contact you if they should have any questions.

Finally, remember that contact should be made between legislative sessions and during holidays when the official is in her or his home district. The structure and content of the visit should be similar to that of a written contact. That is, know your issue, keep it short, identify the issue by its bill number and title, and communicate exactly what action you want the senator or representative to take. Box 17.1 is a list of specific “Dos and Don’ts When Lobbying.” As you begin lobbying, add your recommendations to the list.

If you cannot visit your representative because of time or travel restrictions, a well-written letter, e-mail, or telephone call can communicate your message. Examine the sample letter in Box 17.2. Note that some pointers are listed at the foot of the page. Examples of the proper way to address a public official can be found in Box 17.3.

Letters are common methods of communicating with elected officials; however, a telephone call, fax, or e-mail is often necessary to relay your opinion when time is limited before an important vote. The suggested format and content of the e-mail and telephone message are similar to that of a letter or face-to-face interview.

Deciding on the type of contact to make with the decision maker will vary depending on the situation. For example, if the bill is coming up for the first time in committee, the strategy may be that 10 to 15 people write letters or e-mails or call the members of the committee. At this point, the number of contacts with the office is important. The reason is that the legislator’s assistant typically answers the telephone or opens the mail, tallies the subject of the contact, and puts a hash mark in the “Pro HB 23” or “Con HB 23” column for the bill. Therefore, a greater impact will be realized if multiple contacts pertain to one bill. Bags of form letters, however, may have a negative impact on a lobbying effort. Make sure your callers/writers understand the issue and are able to individualize their contact with the elected official. People who contact the legislator’s office with a script that they do not understand will not further the lobbying efforts of an organization.

The aforementioned efforts are sufficient early in the process; however, if a major controversial bill is coming up for a final vote in the Senate, activating a statewide network and bombarding the senators with letters, e-mails, telephone calls, faxes, and telegrams—as many as possible—is a typical strategy. The bigger the issue, the bigger the campaign should be.

At several points in a lobbying season, but certainly after contacting the elected official for a major vote, a follow-up thank-you letter will strengthen your contact with the legislator and help establish you in her or his political network. In addition to reinforcing the reason for your original contact, thank the official for her or his concern with the issue and the work in solving the problem by writing the bill, voting for it (or whatever), and for paying attention to your concern (Critical Thinking Box 17.6).

In summary, there are specific skills to learn for effective political involvement. But remember that many of the skills needed to be politically savvy are the very ones that will serve you well in everyday professional negotiations (Fig. 17.3).

As a recent graduate who is becoming oriented to your first job and is beginning to look around at what you and your colleagues need to improve, you will agree that political involvement is necessary to reach your goals.

Margaret Mead said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” The nursing profession has much to accomplish in addressing the problems with affordable, readily available health care for all. Make sure you are a part of the solutions that will be discovered in the future!

Controversial Political Issues Affecting Nursing

Uniform Core Licensure Requirements

What Is It?

The Nursing Practice and Education Committee, formed by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), proposed the development of core licensure requirements. This was in response to an increasing concern regarding the mobility of nurses and the maintenance of licensure standards to protect the public’s health, safety, and welfare. With the implementation of Mutual Recognition, it is important that health care consumers have access to nursing services that are provided by a nurse who meets consistent standards, regardless of where the consumer lives. NCSBN (2011) defines competence as “the application of knowledge and the interpersonal, decision-making, and psychomotor skills expected for the nurse’s practice role, within the context of public health, welfare, and safety” (p. 3).

The competence framework is based on the recommendations from the 1996 Continued Competence Subcommittee. This framework consists of the following three primary areas:

▪ Competence development: the method by which a nurse gains nursing knowledge, skills, and abilities

▪ Competence assessment: the means by which a nurse’s knowledge, skills, and abilities are validated

▪ Competence conduct: refers to health and conduct expectations, including assurance that licensees possess the functional abilities to perform the essential functions of the nursing role

An interesting question proposed by the committee was Do you really think nursing is that much different, that much safer on your side of the state boundary line (NCSBN, 1999, p. 3)? The summary of the proposed competencies and the 2005 Continued Competence Concept paper may be found at the National Council’s website (www.ncsbn.org), which includes the rationales for the proposed requirements and a discussion of how the committee developed the recommendations.

Agreements, known as nurse licensure compacts (NLC), specify the rights and responsibilities of nurses who choose or who are required to work across state boundaries and the governing body responsible for protecting the recipients of nursing care. At press time, 25 states including Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin have enacted nurse licensure compacts (NCSBN, 2015). Visit the NCSBN website for a map of the enacted and pending NLC states (https://www.ncsbn.org/nlc.htm).

States entering into NLC agree to recognize mutually a nursing license issued by any of the participating states. To join the compact, states must enact legislation adopting the compact. The nurse will hold a single license issued by the nurse’s state of residence. This license will include a “multistate licensure privilege” to practice in any of the other compact states (both physical and electronic). Each state will continue to set its own licensing and practice standards. A nurse will have to comply only with the license and license renewal requirements of her or his state of residence (the one issuing the license), but the nurse must know and comply with the practice standards of each state in which she or he practices (NCSBN, 2015) (Critical Thinking Box 17.7).

As these agreements are established, experience with additional problems arising from the multistate practice of nursing will be identified and solved in amendments to state practice acts.

Nursing and Collective Bargaining

March! There are no bunkers, no sidelines for nursing today. We find ourselves the center of attention. As the government and corporate America fight escalating health care costs, AIDS is wreaking havoc and technology swells unchecked. Underpaid, overworked, and overstressed nurses are in the midst of a conflagration. Nursing is in greater demand than ever before. Remember Scutari. We must organize, unite, go on the offensive.

Margretta Madden Styles, 1988, quoted in Hansten and Washburn, 1990, p. 53.

The National Labor Relations Act is a federal law regulating labor relations in the private business sector (extended to voluntary, nonprofit health care institutions in 1974). This law grants employees the right to form, to join, or to participate in a labor organization. Furthermore, the law gives employees the right to organize and bargain with their employers through a representative of their own choosing.

Collective bargaining continues to be a point of debate among nurses. Those supporting collective bargaining argue that it is a tool to force positive changes in the practice setting or a method of controlling the practice setting. Many positive changes in the clinical setting are attributed to advances made during contract negotiations.

Opponents feel that as a profession, nurses should not use collective bargaining but instead should influence the practice setting by employee and employer working as a team and not as adversaries. They contend that a strike, the ultimate tool of any labor dispute, should not be used. Opponents further argue that practice standards are not negotiable. The points of disagreement between employer and employee are almost always economic: pay, vacation, sick leave, and similar issues. Chapter 18 presents a more detailed discussion of collective bargaining issues. Regardless of your opinion of collective bargaining, the process will involve political action.

What do you think? A paragraph in the ANA’s publication What You Need to Know About Today’s Workplace: A Survival Guide for Nurses summarizes the challenge for us, and the words are still accurate today:

In a work environment that is constantly changing, it is imperative that nurses are able to assess the true merits of various labor-management structures, to evaluate the real value of proposals to upgrade compensation packages, to determine appropriate levels of participation in workplace decision-making bodies, and to distinguish between long-range solutions and “quick fixes” to workplace problems (Flanagan, 1995, p. 5).

Equal Pay for Work of Comparable Value or Comparable Worth?

The concept of comparable worth or pay equity holds that jobs that are equal in value to an organization ought to be equally compensated, whether or not the work content of those jobs is similar. Pay equity relates to the goal of equitable compensation as outlined in the Equal Pay Act of 1963, and “sex-based wage discrimination” is a phrase that refers to the basis of the problems defined by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

As long ago as World War II, the War Labor Board suggested that discrimination probably exists whenever jobs traditionally relegated to women are paid below the rate of common-labor jobs such as janitor or floor sweeper. One of the first cases was that of the International Union of Electrical Workers v. Westinghouse. The union proved that male–female wage disparity existed and uncovered a policy in a manual that stated that women were to be paid less, because they were women. Back pay and increased wages were given in an out-of-court settlement in an appellate-level decision.

It was nurses who initiated the action in Lemons v. the City and County of Denver. Nurses employed by the city of Denver claimed under the Civil Rights Act that they were the victims of salary discrimination, because their jobs were of a value equal to various better paid positions throughout the city’s diverse workforce. The court ruled that the city was justified in the use of a market pricing system (a form of pay based on supply and demand) even though it acknowledged the general discrimination against women. The court said that the case (and the comparable-worth concept) had the potential to disrupt the entire economic system of the United States. Because of this judgment and the fact that the nurses were unable to prepare a job evaluation program to substantiate their claim, the judge dismissed the case.

Legislative Campaign for Safe Staffing

The ANA has launched a campaign for legislative changes to address safe staffing. Safe Staffing Saves Lives is a national campaign to advocate for safe staffing legislation. As stated on ANA’s website (www.safestaffingsaveslives.org), “ANA believes that staffing ratios should be required by legislation, but the number itself must be set at the unit level with RN input, rather than by the terms of the legislation” (ANA, 2008, p. 1). The position of ANA is not to demand fixed nurse–patient ratios but to develop a system that takes into account the variables that are present and to determine a safe staffing ratio. Principles that address patient safety, quality control, and patient access to care are necessary to establish a foundation for national legislation (Trossman, 2008).

In March 2008, ANA conducted a Safe Staffing Saves Lives Summit: Conversation and Listening Session. Representatives of state associations, nursing specialty, and other health care organizations, as well as representatives from health care facilities, were present. The purpose of the session was to address the issue of preventing peaks in patient flow as a method of improving the RN workload. Hospitals cannot afford to provide peak staffing 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. At Boston Medical Center (BMC), elective surgeries were scheduled to avoid peaks in patient census and to maintain a more predictable census. According to a representative from the BMC, this approach had a very positive impact on predicting and maintaining safe staffing on the nursing units (Trossman, 2008).

From the ANA website on safe staffing: “ANA’s proposal is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach to staffing. Instead, it tailors nurse staffing to the specific needs of each unit, based on factors including patient acuity, the experience of the nursing staff, the skill mix of the staff, available technology, and the support services available to the nurses. Most importantly, this approach treats nurses as professionals and empowers them at last to have a decision-making role in the care they provide” (Trossman, 2008, p. 1).

ANA (2015b) released a study called “Optimal Nurse Staffing to Improve Quality of Care and Patient Outcomes: Executive Summary.” This study conducted a targeted review of recent published articles dealing with nurse staffing and patient outcomes. A panel was also convened consisting of experts in the field of nurse staffing. ANA believes that nurses themselves should be empowered to create staffing plans due to the complex nature of staffing and the large number of variables. ANA continues to stress that staffing is too complex to simply legislatively mandate staffing ratios. The study also stresses the evidence that appropriate staffing has a demonstrated effect on a variety of patient outcomes. Nurses can use the study to advocate for and implement sound evidence-based staffing plans.

In 2013, the Registered Nurse Safe Staffing Act (H.R. 2083/S. 1132) was endorsed by ANA. This would require Medicare-participating hospitals to establish registered nurse (RN) staffing plans using a committee, comprised of a majority of direct-care nurses, to ensure patient safety, reduce readmissions and improve nurse retention. As the act moved forward it was introduced into the House of Representatives in April 2015 as the 2015 Registered Nurse Safe Staffing Act (H.R. 2083) and required amendments to title XVIII (Medicare) of the Social Security Act, requiring Medicare participating hospitals to implement hospital-wide staffing plans for nursing services among other requirements.

At the time of this publication, seven states have enacted safe staffing legislation using the Registered Nurses Safe Staffing Act’s committee approach: Oregon, Texas, Illinois, Connecticut, Ohio, Washington, and Nevada (ANA, 2015c).

Much work still needs to be done in the area of safe staffing. Nurses are very concerned about staffing issues—mandatory overtime, increased numbers of assistive personnel replacing licensed personnel, and increased patient acuity are factors contributing to the problem. Changes will be achieved as we educate the public, as well as legislative representatives, and as nurses take the primary role to initiate changes in the workplace environment.

Conclusion

Politics, policy making, and advocating for patients are key processes for nurses to claim their “power” as a driving force in health care. Participating in ANA-PAC activities provides an opportunity to be at the grassroots level of lobbying (see the Relevant Websites and Online Resources below). Shaping policy and becoming active in the legislative area are practice roles for nurses. By having an understanding of the political process, nurses can and will make significant strides in promoting legislation that will positively affect the health of the nation.