Chapter 28 Poisoning, overdosage, drugs and alcohol

POISONING AND OVERDOSAGE

Assessment

History

Investigations

Depending on the clinical setting other investigations would include:

Principles of management

Resuscitation, stabilisation and supportive care

All patients with an overdose should have intravenous access.

Decontamination

Gastrointestinal (GI) decontamination

The efficacy of activated charcoal is time-dependent and therefore should be considered mainly in those presenting within 1 hour when the poisoning is assessed to be high-risk. The main complication of charcoal is pulmonary aspiration, especially in the obtunded patient. Toxins not well adsorbed by charcoal are listed in Table 28.1. Activated charcoal is also available with a cathartic (e.g. sorbitol). There is little evidence to suggest that the addition of a cathartic is superior to using activated charcoal alone.

| Drug group | Examples |

|---|---|

| Alcohols | Ethanol, methanol, isopropyl glycol, ethylene glycol |

| Metals | Lithium, iron, mercury, potassium, lead, arsenic |

| Acids and alkalis | |

| Hydrocarbons | Turpentine, kerosene, eucalyptus oil, benzene |

Elimination

Multiple doses of charcoal may decrease drug absorption in some cases (Box 28.2). A suggested dosing regimen would be 25 g (adults) or 0.5 g/kg (children) every 2–4 hours. It is contraindicated if there is a bowel obstruction or decreased level of consciousness in a patient without a protected airway. Always check for the presence of bowel sounds before administering the next dose.

Box 28.2 Situations when multiple doses of charcoal may reduce drug absorption

Urinary alkalinisation may be used for increasing elimination of weak acids. This can be achieved by intravenous administration of sodium bicarbonate. Give a bolus of 1 mmol/kg IV followed by an infusion (100 mmol of sodium bicarbonate in 1000 mL 5% dextrose in 0.9% saline over 4 hours). Adjust the rate to a urinary pH > 7.5. Complications of bicarbonate therapy include fluid overload, alkalaemia, hypokalaemia and hypocalcaemia. Main indication is salicylate overdose.

Dialysis is the most commonly used form of extracorporeal elimination. It can enhance elimination of various toxins (Box 28.3). Indications for dialysis are listed in Box 28.4.

Specific therapies

Cardiovascular instability

Hyperthermia

TOXIDROMES AND SPECIFIC OVERDOSES

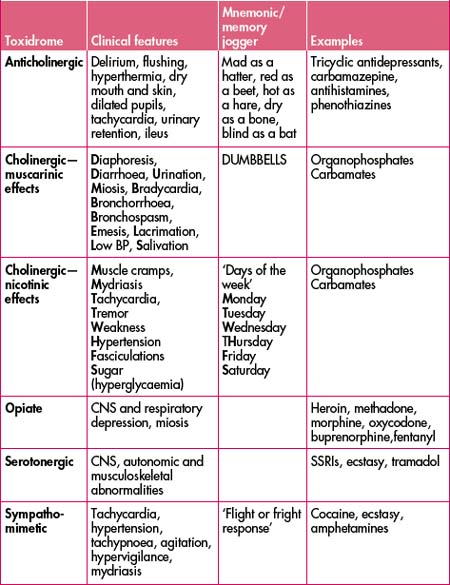

The clinical presentation of some poisonings may be predictable based on the pharmacology of the drug/substance involved. Some classic toxidromes with examples are listed in Table 28.2.

Opioids

This group of drugs includes those derived from opium as well as those that have opiate-like activity. Typical toxic effects are CNS and respiratory depression and miosis. Acute lung injury has been reported, typically occurring once ventilation has been restored following a period of respiratory depression. Other effects include mild hypotension (arteriolar and venous vasodilation). Treatment of opioid toxicity is supportive, especially of the airway and ventilation, and sometimes involves the use of naloxone, either as bolus dose(s) or infusion. Several drugs in this group have atypical toxic effects (Table 28.3).

| Opioid | Atypical toxic effects of clinical significance |

|---|---|

| Tramadol | Serotonergic syndrome, seizures |

| Dextropropoxyphene | Seizures, wide QRS arrhythmias, negative inotropic effects (Na channel blockade) |

| Methadone | Prolonged QT interval (possibly → torsades de pointes) |

| Pethidine | Seizures |

| Fentanyl | Muscle rigidity (rapid injection) |

Key points—opioids

Paracetamol

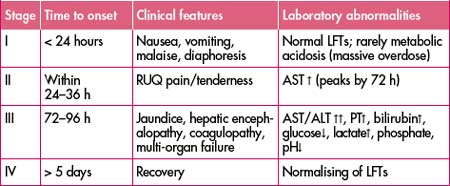

Paracetamol overdoses can be either single or staggered ingestions. There are four described stages of paracetamol poisoning (Table 28.4). Stage II marks the onset of liver injury. Renal failure is seen in 25–50% of those with hepatic dysfunction. Death is usually due to multi-organ failure, sepsis, haemorrhage, acute respiratory distress syndrome and/or cerebral oedema. Key blood tests are paracetamol level and transaminases—aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Prothrombin time (PT) may also be indicated. Paracetamol levels are reported in various units (mg/L or μmol/L). When plotting the paracetamol level on the nomogram, always check the units are corresponding to the correct axis. Failure to do so may be life-threatening.

Paracetamol can be implicated in an accidental overdose. Remember to ask quantities of paracetamol ingested in the patient who has been self-medicating to achieve analgesia. Paracetamol is a common component of over-the-counter medications such as cold and flu preparations and migraine tablets. Serious hepatotoxicity is less common in children compared to adults. Charcoal can be given in those who present within 1 hour after potentially toxic ingestions.

Key points—paracetamol

Guidelines and treatment nomogram

General key points

Management of acute single ingestions

Management of staggered ingestions

Repeated supratherapeutic ingestion

Table 28.5 Repeated supratherapeutic doses that may be associated with hepatic injury

| Adults and children aged > 6 years | Children aged < 6 years |

|---|---|

| > 200 mg/kg or 10 g (whichever is less) over a single 24-hour period | ≥ 200 mg/kg over a single 24-hour period |

| 150 mg/kg or 6 g (whichever is less) per 24-hour period for the preceding 48 hours | ≥ 150 mg/kg per 24-hour period for the preceding 48 hours |

| > 100 mg/kg or 4 g/day (whichever is less) in patients with predisposing risk factors (e.g. chronic alcohol use, use of enzyme-inducing drugs, prolonged fasting, dehydration) | ≥ 100 mg/kg per 24-hour period for the preceding 72 hours |

Sustained-release paracetamol

Key points—N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

Illicit drugs

The majority of these are best divided into stimulants versus depressants (Tables 28.6 and 28.7). The others can be classed as hallucinogens (Table 28.8). Amyl nitrite is considered alone.

| Drug name | Common street names |

|---|---|

| Cocaine | Coke |

| Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) | Ecstasy |

| Methamphetamine (MDA) | Ice, speed |

| Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) | Red mitsubishi∗, Dr Death |

| Para-methoxymethylamphetamine (PMMA) | |

| 4-methylthioamphetamine (4-MTA) | Flatliner |

∗ Not all pills with the red mitsubishi logo contain PMA.

| Drug name | Common street names |

|---|---|

| Heroin | |

| Gamma-hydroxybutyrate | G, GBH, fantasy, grievous bodily harm |

| Ketamine | Special K |

Table 28.8 Hallucinogens and others

| Hallucinogens | Others |

|---|---|

| Cannabinoids LSD (‘acid’) | Amyl nitrite (‘poppers’) |

Stimulants

Cocaine and the amphetamines act via stimulation of the central and peripheral adrenergic receptors. They are sympathomimetic agents. The most common clinical effects of this group of drugs are outlined in Table 28.9.

| System | Clinical effect |

|---|---|

| CNS |

Cocaine

Amphetamines (MDMA, MDA, PMA, PMMA, 4-MTA)

| Autonomic dysfunction | Neuromuscular dysfunction | CNS dysfunction |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperthermia | Myoclonus | Confusion |

| Diaphoresis | Hyperreflexia | Disorientation |

| Sinus tachycardia | Muscle rigidity | Agitation |

| Hypertension | Tremor | Coma |

| Hypotension | Hyperactivity | Anxiety |

| Tachypnoea | Ataxia | Hypomania |

| Dilated pupils | Shivering | Lethargy |

| Unreactive pupils | Seizures | Insomnia |

| Flushed skin | Nystagmus | Hallucinations |

| Diarrhoea | Teeth chattering | Dizziness |

Key points—stimulants

Depressants

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and analogues

This group of drugs consists of GHB, gamma-butyrolactone and 1,4 butanediol. They exhibit similar clinical effects. GHB was initially developed as an anaesthetic agent in the 1960s. It is a clear, colourless and reasonably tasteless drug with minimal ‘hangover’ effect which makes it palatable to the user and also accounts for it being implicated sometimes as a ‘date rape’ drug. The most prominent clinical feature of toxicity is a rapid onset of coma, often to a GCS as low as 3 (Box 28.5). Varying GCS over a short period of time can also occur. For example, a patient can oscillate from GCS 6 to 10 and then back to 6 in a period of 15–30 minutes. This phenomenon typically occurs as the drug effects are subsiding.

Key points—GHB

Hallucinogens

Cannabinoids

| Psychological |

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

Key points—hallucinogens

Amyl nitrite

Key points—methaemoglobinaemia

| % Methaemoglobinaemia | Clinical features |

|---|---|

| 10–20% | Cyanosis |

| 20–50% | Shortness of breath (SOB), dizziness, fatigue, headache |

| > 50% | Tachypnoea, lethargy, coma, seizures, death |

Beta-blockers

| Cardiovascular |

Management

Calcium channel blockers

The centrally acting calcium channel blockers (Table 28.14) are the most cardiotoxic in this group and effects can be delayed (up to 16 hours) due to the sustained-release preparations available. Clinical features are outlined in Table 28.15.

| Centrally acting | Peripherally acting |

|---|---|

| Verapamil | Amlodipine |

| Diltiazem | Felodipine |

| Nifedipine | |

| Lercanidipine |

Table 28.15 Clinical features of calcium channel blocker overdose

| Cardiovascular |

Management

Organophosphates and carbamates

Management

Delayed syndromes include an intermediate syndrome and also encephalopathy and neuropathies. Intermediate syndrome describes muscle weakness or other cholinergic symptoms that appear 24–96 hours after acute exposure to organophosphates.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

TCAs are antihistaminic, anticholinergic and block sodium and potassium channels. Overdoses are life-threatening, particularly at doses of > 10 mg/kg. Signs of toxicity (Table 28.16) are evident within 2 hours of ingestion and rapid deterioration can occur. Early intervention with management of coma, hypotension, seizures and arrhythmias is life-saving.

| CNS |

Key points—TCAs

DRUGS AND ALCOHOL

Problems resulting from alcohol and drug use can be classified as:

After dealing with the presenting complaint, some attempt must always be made by the emergency medical officer to intervene effectively with the underlying cause of the presentation, i.e. the alcohol or drug use. An effective intervention could be as simple as an explanation or a referral.

Alcohol

Acute presentations

Overdose

Alcohol Withdrawal Scale

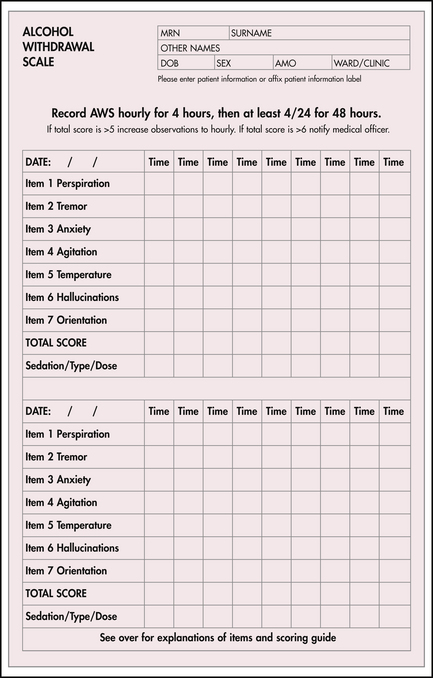

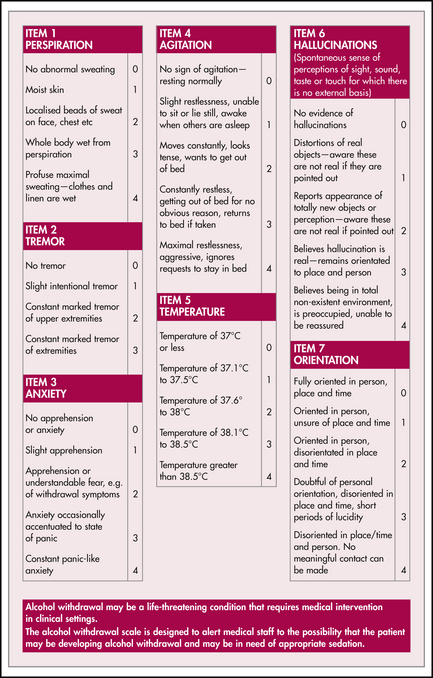

The Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (AWS, see Figure 28.l) is a widely used, simple instrument for measuring the signs of alcohol withdrawal. It has several virtues: the fact that it is a standardised instrument encourages a better quality of care. The simplicity of the AWS makes it easy to use and encourages an earlier response. However, like all other instruments used in medicine, the AWS must be applied critically. The signs of alcohol withdrawal can be produced in many other conditions. Therefore, the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal should always be reviewed and reconsidered in patients who do not respond quickly to treatment.

Alcohol withdrawal

Management

Chronic presentations

Central nervous system (CNS)

Trauma

Patients presenting with multiple injuries (including head injuries) are often severely intoxicated.

Alcohol dependence

Management of drinking problems

Diagnosis

Assessment

Tobacco

Wherever possible patients, relatives, visitors and staff must be discouraged from smoking for the comfort of the majority of the population who are non-smokers and, more importantly, because of the (now appreciated) hazards of passive smoking.

Opioids

Acute presentations

Withdrawal

Opioid withdrawal is objectively milder than alcohol withdrawal and has been likened to a ‘bad cold’. However, many experiencing heroin withdrawal complain about very distressing symptoms. Withdrawal can be recognised in patients who are often restless, have a tachycardia and sweat profusely. They may complain of diarrhoea, abdominal cramps or a curious nasal snuffling may be apparent. The pupils are widely dilated. The most helpful objective signs are mydriasis and gooseflesh which can sometimes be seen fleetingly across the trunk and abdomen. Patients in opioid withdrawal should be referred to specialist detoxification centres (when available) unless a medical or surgical condition requires hospital admission.

Assessment

A history of the patient’s drug use and drug dependence should be obtained and specific enquiry made about medical and non-medical opioid-related problems. Ask ‘have you ever injected drugs?’ rather than ‘are you a drug user?’.

Management plan

(Also see ‘Benzodiazepines’ in the ‘Poisoning and overdosage’ section above.)

Withdrawal

Prescribed drugs

Emergency physicians should always be cautious about prescribing parenteral opioids to patients not known to the hospital, especially if the patient presents just before closing time, appears very familiar with drug names which are often slightly misspelt or mispronounced. Characteristic presentations are renal colic, backache, migraine or pancreatitis. Wherever possible, some objective evidence of the condition should be obtained, e.g. inspect freshly voided urine (passed under supervision) for the presence of microscopic haematuria in renal colic. Take-away doses of parenteral opioids should not be provided unless there is a good indication, e.g. disseminated malignancy or authentic letter from a medical practitioner. Avoid the prescribing of pethidine, which is responsible for most difficult cases of iatrogenic dependence.

Cocaine

(Also see ‘Cocaine’ in ‘Poisoning and overdosage’ above.)

Overdose

Australian Drug Information Network website. http://www.adin.com.au/.

Cami J., Farre M. Mechanisms of disease: drug addiction [review article]. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):975-986.

General Toxic Poisoning and Drug Overdose Clinical Resources. Online. Available: http://fsumed-dl.slis.ua.edu/clinical/emergency/conditions/toxicities/overdose.htm.

Goldfrank L.R., et al. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies, 7th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

Harrison’s On Line. Biology of addiction. Online. Available: http://harrisons.accessmedicine.com/server-java/Arknoid/amed/harrisons/co_chapters/ch386_p01.html.

Harrison’s On Line. Cocaine and other commonly used drugs. Online. Available: http://harrisons.accessmedicine.com/server-java/Arknoid/amed/harrisons/co_chapters/ch389_p01.html#.

Ward J., Mattick R., Hall W., editors. Methadone maintenance treatment and other opioid replacement therapies. Amsterdam: Harwood, 1998.