9 Poisoning

Etiology and Pathogenesis

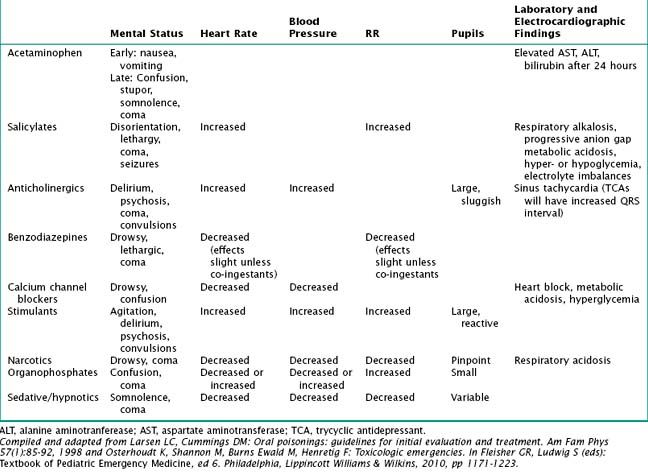

The mechanism of toxicity varies from one agent to another, yet there are some classic presentations that can be seen with particular ingestions (Table 9-1). Ingestions that can be lethal in small doses are reviewed in more depth here.

Table 9-1 Clinical Manifestations of Selected Toxic Ingestions

| Ingestion | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia early in course; late findings of jaundice and liver failure |

| Antihistamines | Initially CNS depression but stimulation in higher doses (hyperactivity, tremors, hallucinations, seizures) |

| Aspirin | Tachypnea, respiratory alkalosis, metabolic acidosis, tinnitus, coagulopathy, slurred speech, seizures |

| β-Blockers | Bradycardia, hypotension, coma or convulsions, hypoglycemia, bronchospasm |

| Calcium channel blockers | Bradycardia, hypotension, junctional arrhythmias, hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis |

| Caustics | Coagulation necrosis (acid) or liquefaction necrosis (alkali), scarring, strictures, burning, dysphagia, glottic edema |

| Digoxin | Nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances, lethargy, electrolyte disturbances, hyperkalemia, prolonged AV dissociation and heart block, arrhythmias |

| Disc batteries | Corrosive when in contact mucosal surfaces |

| Ethanol | Nausea, vomiting, stupor, anorexia; late toxicity: triad of coma, hypothermia, hypoglycemia Lethal (cardiorespiratory depression) if >400-500 mg/dL (life-threatening hypoglycemia may occur at much lower levels in young children) |

| Ethylene glycol | CNS depression, metabolic acidosis, convulsions and coma, hypocalcemia, renal failure Laboratory findings: anion gap metabolic acidosis, osmolal gap, urine oxalate crystals |

| Hypoglycemic agents | Hypoglycemia, coma, seizures |

| Iron | Hemorrhagic necrosis of GI mucosa, hypotension, hepatotoxicity, metabolic acidosis, coma, seizure, shock |

| Isopropyl alcohol | Altered mental status, gastritis, hypotension Laboratory findings: elevated osmolal gap, ketonuria (no metabolic acidosis or hypoglycemia) |

| Lead | Abdominal pain, constipation, anorexia, listlessness, encephalopathy (peripheral neuropathy; rare in children), microcytic anemia |

| Methanol | CNS depression, delayed metabolic acidosis, optic disturbances Laboratory findings: anion gap metabolic acidosis, osmolal gap |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Lethargy, disorientation, ataxia, urinary retention, decreased GI motility, coma, seizures Cardiovascular alterations: sinus tachycardia, widened QRS complex; may progress to hypotension, ventricular dysrhythmias, cardiovascular collapse |

AV, atrioventricular; CNS, central nervous systeml; GI, gastrointestinal.

Compiled from Eldridge DL, Van Eyk J, Kornegay C: Pediatric toxicology. Emerg Med Clin North AM 15:283-308, 2007 and Osterhoudt K, Shannon M, Burns Ewald M, Henretig F: Toxicologic emergencies. In Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds): Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 6. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010, pp 1171-1223.

Calcium Channel Blockers and Beta-Adrenergic Blockers

Calcium channel blockers are most often used to treat hypertension, angina, migraines, and glaucoma, and they work by antagonizing L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle and cardiac tissue. By preventing calcium influx into these cells, calcium antagonists cause vasodilatation as well as depression of both myocardial conduction and contractility. In large doses, this can lead to life-threatening bradycardia, heart block, and hypotension. Beta-adrenergic blockers can have similar cardiotoxicity in overdose (Table 9-1).

Clinical Presentation

Patients with poisonings may present with a wide array of clinical signs and symptoms. Most often, children present with nonspecific signs, including nausea and vomiting, as well as altered mental status. Depending on the exposure, patients may also have burns or rashes, alterations in their respiration, and metabolic changes that are not typically seen in a more common illness. Nevertheless, there are characteristic clinical features, representing in particular altered central and autonomic nervous system findings, which have been termed “toxidromes” (Table 9-2).

Evaluation and Management

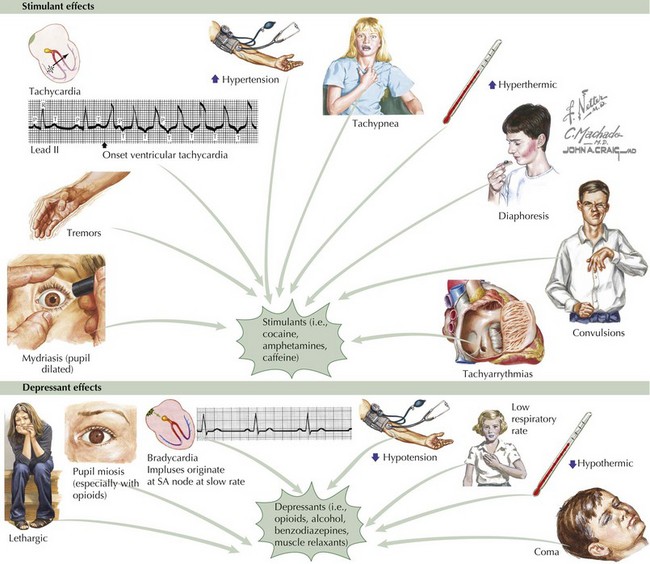

In addition to the history, the physical examination of a patient with a poisoning can be extremely revealing. Close attention to heart rate, respiratory pattern, pupillary response, mental status, abdominal examination, and reflexes can be clues to particular exposures. For example, patients poisoned with stimulants, including cocaine, amphetamines, caffeine, and theophylline, present with mydriasis, tremors, tachycardia, hypertension, tachypnea, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, mania, convulsions, and tachyarrhythmias (Figure 9-1). Poisoning with depressants, on the other hand, including opioids, alcohol, benzodiazepines, and muscle relaxants, can lead to lethargy, decreased responsiveness to verbal and physical stimulation, miosis (especially opioids, barbiturates, and alcohol), bradycardia, hypotension, bradypnea, hypothermia, and coma (see Figure 9-1). Other signs and symptoms characteristic of a particular substance can be characterized as a toxidrome (Table 9-2).

Cathartics

Some poisonings are amenable to specific antidotal therapy, which may counter the toxin itself or its dangerous metabolites (Table 9-3). Three treatments in particular—oxygen (for any patient with hypoxia, carbon monoxide exposure, or cyanide toxicity), glucose (for hypoglycemia caused by insulin, oral hypoglycemics, ethanol, and so on), and naloxone (for opioid-induced respiratory depression)—are important and safe enough to consider for emergent use as empiric therapy for altered mental status in suspect cases. The local poison control center is another valuable resource to help ensure adequate patient management regardless of the exposure. All poisonings or suspected poisonings should be reported to the local poison control center (800-222-1222) so they can assist with appropriate treatment and monitoring on a case-by-case basis.

Table 9-3 Antidotes and Management of Selected Toxic Exposures

| Ingestion | Potential Antidote / Other management |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | N-acetylcysteine, activated charcoal within 4 hours |

| Antihistamines | Activated charcoal or WBI for extended-release formulations, anticonvulsants, physostigmine |

| Benzodiazepine | Flumazenil |

| β-adrenergic blockers | Glucagon, activated charcoal if early after ingestion, WBI for delayed-release formulations, atropine, IVF, pressors |

| Calcium channel blockers | Calcium, activated charcoal if early after ingestion, WBI for delayed-release formulations, atropine, IVF, pressors, insulin/glucose |

| Carbon monoxide | 100% oxygen, hyperbaric oxygen |

| Caustic agents | ABCs, steroids for esophageal burns (controversial); in-hospital monitoring for mediastinitis, pneumonitis, and peritonitis |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | Atropine, pralidoxime |

| Cyanide | ABCs, 100% oxygen, sodium nitrite/sodium thiosulfate or hydroxocobalamin |

| Digoxin | Digoxin immune FAb, activated charcoal, electrolyte management |

| Disc batteries | Removal if in esophagus; if below esophagus, watch for 3 days, and if not out, then consult regarding potential removal |

| Ethanol | Respiratory management, correction of hypoglycemia, temperature control, thiamine (in chronic alcoholism) |

| Ethylene glycol and methanol | Ethanol or 4-methylpyrazole if level >20 mg/dL, sodium bicarbonate, calcium, pyridoxine, thiamine, folate, hemodialysis |

| Iron | Deferoxamine, WBI, hemodynamic support for possible GI bleed, management of acidosis, hypoglycemia, and hypotension |

| Isoniazid | Pyridoxine |

| Lead | Chelation with edetate calcium disodium, 2,4-dimercaptopropanol, succimer, and anticonvulsants as needed |

| Methemoglobinemic agents | Methylene blue |

| Opioids | Naloxone |

| Salicylates | Correct electrolytes, fluid resuscitation, urine alkalinization, hemodialysis |

| Sulfonylurea | Dextrose, octreotide |

| TCAs | Sodium bicarbonate to reduce cardiotoxicity, pressor support prn, activated charcoal |

ABCs, airway, breathing, and circulation; GI, gastrointestinal; IVF, intravenous fluids; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; WBI, whole-bowel irrigation.

Compiled and adapted from Larsen LC, Cummings DM: Oral poisonings: guidelines for initial evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Phys 57(1):85-92, 1998 and Osterhoudt K, Shannon M, Burns Ewald M, Henretig F: Toxicologic emergencies. In Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM (eds): Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, pp 951-1007.

Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, et al. 2007 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(10):927-1057.

Eldridge DL, Van Eyk J, Kornegay C. Pediatric toxicology. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;15:283-308.

Erickson TB, Ahrens WR, Aks SE, et al. Pediatric Toxicology: Diagnosis and Management of the Poisoned Child. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2004.

Larsen LC, Cummings DM. Oral poisonings: guidelines for initial evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Phys. 1998;57(1):85-92.

Osterhoudt K, Shannon M, Burns Ewald M, Henretig F. Toxicologic emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:1171-1223.

Tenenbein M. Recent advances in pediatric toxicology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46(6):1179-1188.