Chapter 63 Poisoning

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Poisoning is defined as exposure to a potentially toxic substance and can occur by ingestion, inhalation, or absorption through the skin. The most frequent substances for poison exposures in the child less than 6 years of age are those that are readily available in the environment such as cosmetics, plants, cleaning supplies, pain medication, and cough and cold remedies. Pharmaceuticals are involved in a significant number of the fatalities resulting from pediatric poisonings. Poison control centers, safety education, and child-resistant packaging for drugs and hazardous chemicals have contributed to prevention of poisoning in children.

Childhood lead poisoning occurs when lead is absorbed, primarily through the gastrointestinal tract, after ingestion of lead-contaminated substances. Lead-based paint is the most common source and serious cause of lead poisoning. Children are exposed to lead-based paint when they ingest the fine dust particles from lead-based paint, paint chips from the walls of old homes, or lead-contaminated soil. Less common sources of lead include ceramics, hobby materials, and imported canned foods. Lead is a component of several folk remedies used in Mexico (azarcón and greta for digestive problems), the Middle East (farouk rubbed on gums to help teething, bint al zahib used for colic), and Southeast Asia (pay-loo-ah for fever and rashes). A high incidence of lead poisoning is associated with pica.

Lead poisoning is the excessive accumulation of lead in the blood. The majority of children with lead poisoning are asymptomatic, and diagnosis is often made as a result of screening. A lead level of less than 10 mg/dl indicates no lead poisoning; lead levels of 10 to 14 mg/dl are considered borderline; and lead levels of 15 mg/dl or higher require some degree of intervention. Acute symptoms of lead poisoning are generally not evident until the lead level reaches 50 mg/dl or higher.

Excessive amounts of absorbed lead accumulate in the bones, soft tissue, and the blood. Soft tissue absorption is of great concern because it can result in central nervous system (CNS) toxicity and irreversible renal failure. Late signs of lead toxicity include coma, stupor, and seizures. Lead poisoning is considered chronic if the lead has been accumulated over a period longer than 3 months. Lead interferes with heme synthesis and has a toxic effect on the red blood cells; this results in a decrease in the number of red blood cells and the amount of hemoglobin in cells, which leads to anemia.

INCIDENCE

1. Children under 6 years of age are more likely to have unintentional exposure to poisons compared to adolescents and adults. Adolescents are at risk for poisoning exposures both intentional and unintentional—about half of the poisoning exposures are considered suicide attempts in the adolescents.

2. Most poisonings take place in the home; the most common location is the child’s own residence, and the second most common is the grandparents’ home.

3. Times of peak incidence are evenings at mealtimes, weekends, and holidays.

4. The peak age of incidence for poisoning is between 1 and 3 years, when a child is autonomous and exploring.

5. Lead poisoning peak incidence occurs between 1 and 2 years of age. Children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years who live in poorly maintained older housing are at highest risk.

6. In the United States, about 2% of children less than 6 years of age have blood lead levels of 10 mg/dl or more.

Declines in the incidence are attributed to the elimination of lead from paint, gasoline, and food cans.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The manifestations of poisoning depend on the agent that is ingested. The following are some examples:

Lead poisoning is detected during routine screening of high-risk children because most children are asymptomatic until the lead levels are high. Symptoms that may be seen as lead levels rise include the following:

1. Gastrointestinal: anorexia, constipation or diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or colic

2. Neurologic: irritability and malaise. When lead poisoning is chronic, increased incidence of learning disorders, behavioral disorders, perceptual deficits, and hyperactivity with decreased attention span can be seen

COMPLICATIONS

1. Pulmonary: respiratory arrest, acute respiratory distress syndrome, tracheal corrosion if a caustic substance is ingested

2. Cardiovascular: shock, cardiac arrest, congestive heart failure

3. Gastrointestinal: liver failure, esophageal corrosion if a caustic substance is ingested

Complications of Lead Poisoning Include the Following:

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

The first step in managing poisoning is to assess and support the airway, breathing, and circulation. The child is stabilized by providing oxygen and intravenous fluids and maintaining the airway with intubation if needed. Treatment of shock, congestive heart failure, cerebral edema, and convulsions occurs as needed. Acute poisoning management depends on the amount, toxicity, and time since ingestion or exposure to the poison. The poison may be eliminated from skin contact by removing clothing and liberally washing the contact area. With ocular exposure, eyes are rinsed with water or normal saline.

For ingestions, the use of ipecac syrup to induce vomiting is no longer recommended as a home treatment. While ipecac is considered a safe emetic, it does not completely remove the toxin and may cause continued vomiting, which leads to less tolerance of other orally administered poison treatments. Gastric lavage may be done to remove some poisons, and it may be helpful to send a gastric specimen to the laboratory for identification when the substance ingested is unknown. When the child is comatose, endotracheal intubation is performed before gastric lavage. Activated charcoal is given to bind to the poison in the gastrointestinal tract and is most effective when given soon after the poison has been ingested. Specific antidotes, such as acetylcysteine (Mucomyst) for significant acetaminophen ingestions or naloxone (Narcan) for narcotic ingestions, are used when appropriate.

The primary focus of medical care for lead poisoning is screening and decreasing primary exposure by removing lead sources from the child’s environment. Screening includes assessing risk for lead poisoning at each physician’s appointment. This assessment may be done by asking three risk-assessment questions:

1. Does your child live in or regularly visit a house or child care facility built before 1950?

2. Does your child live in or regularly visit a house or child care facility built before 1978 that is being remodeled or renovated or has been remodeled or renovated within the last 6 months?

3. Does your child have a sibling or playmate who has or did have lead poisoning?

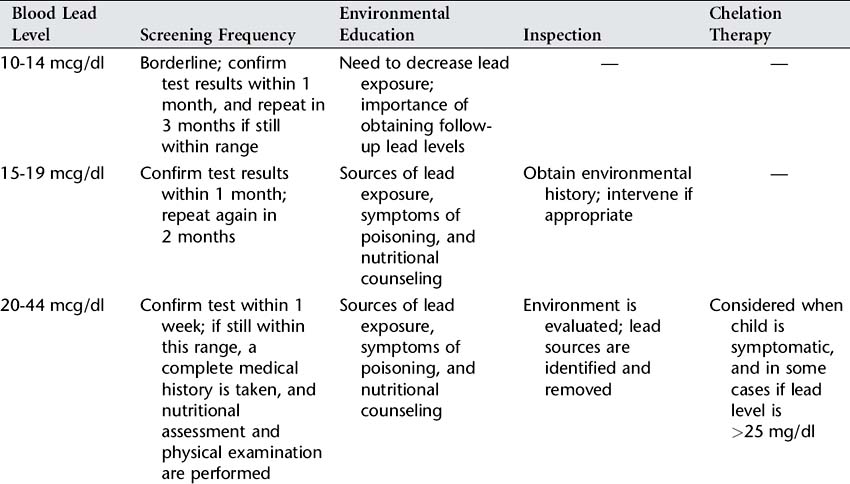

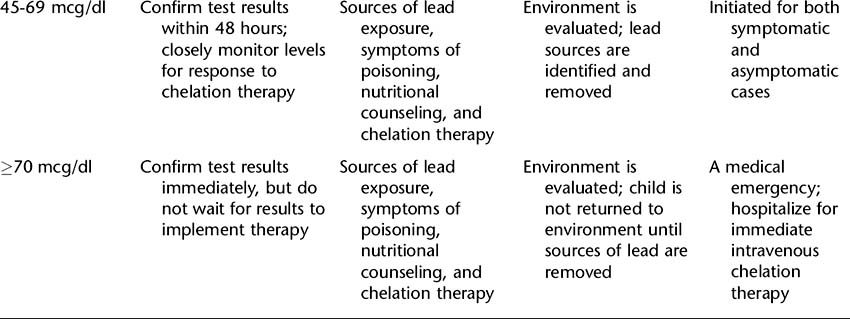

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends targeted screening of children at risk. All Medicaid- eligible children must be screened. State public health officials determine appropriate screening using local data related to blood lead levels and housing data from the census. Table 63-1 summarizes screening frequency, environmental evaluation, education, and medical management based on blood lead level.

When blood lead levels rise above 45 mg/dl, chelation therapy is indicated to reduce lead burden in the body. All drugs used for chelation bind to the lead, which facilitates removal of the lead via urine (and, with some drugs, also via stool) and depletes the amount of lead in the tissues. Before outpatient therapy is begun, the lead must be removed from the child’s environment to prevent possible increased absorption of lead by the chelating drug. Children hospitalized for chelation therapy are not discharged until environmental lead is removed or alternative housing is available. The major chelating agents used for children include succimer and edetate calcium disodium. Chelation therapy is also administered to children who are symptomatic who have blood lead levels lower than 45 mg/dl.

The child admitted to hospital with symptoms of encephalopathy receives immediate intravenous chelation therapy. Lumbar punctures are to be avoided in these children whenever possible. Fluids and electrolyte levels are closely monitored. Fluids may be restricted to basal requirements plus adjustments for fluid losses such as in vomiting. Mannitol is used to decrease cerebral edema and intracranial pressure. Seizures are managed initially with diazepam, followed by long-term anticonvulsant therapy. Iron deficiency anemia must be treated in all affected children. Prognosis and residual effects are related to how high lead levels were and how long they were elevated. Learning disorders and behavioral problems may result from even low levels of lead.

NURSING ASSESSMENT

1. Take detailed history (agent ingested, dose, time of ingestion, underlying problems of child, age and weight of child, signs and symptoms present, treatment rendered).

2. Perform complete system-by-system assessment (see Appendix A).

3. Assess hydration and nutritional status for lead poisoning.

4. Assess home environment for lead source.

5. After child is stabilized and during well-child visits starting around 6 months of age, assess childproofing of home.

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

1. Monitor child during decontamination procedures and until stable.

2. Provide emotional support to child and family (refer to the Supportive Care section in Appendix F).

3. Provide anticipatory guidance related to childproofing the home, especially regarding potential sources of poisoning.

Lead Poisoning Interventions

1. Monitor child’s neurologic status and report changes in level of consciousness, seizure activity, headaches, projectile vomiting, bulging fontanelles, or abnormal pupillary responses.

2. Monitor child’s vital signs and report increased apical pulse, decreased or increased blood pressure.

3. Monitor intake and output, and maintain fluid restrictions.

4. Monitor child’s reaction to chelation therapy.

5. Provide diet with regular meals rich in iron and calcium, low in fat.

Discharge Planning and Home Care

1. Teach parents about poison-proofing at home and poison management.

2. Make sure that all poisonous substances and medicines remain in their original containers, have child-resistant caps, and are out of reach of children.

3. Post poison control center number on telephone. The universal poison control center telephone number in the United States is 800-222-1222; the call will be routed to the local poison control center.

4. Syrup of ipecac is no longer routinely recommended for home use and, if present in the home, should be appropriately discarded.

Additional Lead Poisoning Instructions

1. Instruct parents to identify and remove lead hazards from environment(s) in which child spends considerable time before discharge. Refer to community agencies for environmental evaluation and lead removal, if appropriate.

2. Instruct parents to supervise child with pica more closely and encourage frequent handwashing.

3. Instruct and counsel parents about recommended follow-up services (see Table 63-1).

CLIENT OUTCOMES

1. Child will have minimal injuries related to poisoning.

2. Parents will express their fears and concerns.

3. Parents will understand child’s developmental level as it relates to childproofing home and supervising child appropriately.

4. Child will return to lead-free environment.

5. Child and family will understand importance of follow-up.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):1020.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention. Policy statement: Poison treatment in the home. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1182.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. Policy statement: Lead exposure in children: Prevention, detection, and management. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):1036.

Centers for Disease Control National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Poisonings: Fact Sheet, 2006. (website) www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/poisoning.htm Accessed April 30, 2006

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonfatal, unintentional medication exposures among young children—United States, 2001–2003. MMWR weekly. 2006;55(01):1.

Manogura AS, Cobaugh DJ, Members of the Guidelines for the Management of Poisonings Consensus Panel. Guideline on the use of ipecac syrup in the out-of-hospital management of ingested poisons. Clin Toxicol. 2005;1:1.

Wax PM, et al. β-Blocker ingestion: An evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol. 2005;43:131.