13 Poisoning

Self-poisoning

General points

• 80% of patients seen in A&E will be conscious.

• There is poor correlation between history of amount, type and timing of poisons consumed and blood toxicology.

• Frequently, more than one drug will have been consumed.

• Alcohol is the most commonly consumed second agent.

• Carefully assess suicide risk, be sympathetic and admit to MAU.

What particular points do you need to assess on physical examination?

• Assess and record conscious level using the Glasgow Coma Scale (p. 492).

• Document respiratory rate and cyanosis (use pulse oximetry).

• Measure blood pressure and pulse.

• Record pupillary size (small with opiates) and reactivity to light.

• Measure temperature: rectally if unconscious.

• If depressed consciousness, check for coexistent head injury.

What should you do?

• Baseline: full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function.

• Paracetamol and salicylate levels at 4 h or thereafter post-overdose.

• Blood and urine samples for toxicology: particularly useful in seriously ill with altered consciousness.

• O2 saturation, arterial blood gases if depressed respiration.

Respiratory support

• Protect airway because vomiting is a risk: vomiting is particularly associated with opiates, benzodiazepines, alcohol and tricyclic anti-depressants.

• Respiratory depression might occur with opiates, benzodiazepines, alcohol, tricyclic anti-depressants.

• Monitor with pulse oximetry.

• Give oxygen: start with 60% humidified O2.

• Loss of gag or cough reflex is the prime indication for intubation.

Cardiovascular support

What other problems might occur?

Arrhythmias

• Might arise from hypoxia or metabolic acidosis.

• Bradycardia might occur with beta blockers, digoxin and organophosphorus compounds.

• Ventricular and supraventricular tachycardias occur due to theophyllines, tricyclic anti-depressants/phenothiazines (due to prolonged QT interval) cocaine, Ecstasy and amfetamine.

What specific management procedures are there for overdoses?

Reducing absorption

• Gastric lavage: should only be used for life-threatening overdoses and only within the first hour for significant recovery of poison. Avoid lavage if corrosives, paraffin or petrol have been taken because of risk of inhalation. Always intubate if the patient is unconscious.

• Induced emesis: should not be used because it is ineffective at removal of poison and delays the use of activated charcoal.

• Activated charcoal: binds drugs in the intestine and is valuable for adsorbing most poisons but is most effective for aspirin, tricyclic anti-depressants and theophyllines. For most drugs do not use more than 1 h post-ingestion of poison or with an oral antidote (see also Active elimination, below).

Active elimination

• Repeated doses of charcoal might enhance elimination for selected drugs even after the drug has been absorbed. This works for aspirin, barbiturates, quinine, theophylline and carbamazepine.

• Whole bowel irrigation using non-absorbable polyethylene glycol solution (not to be confused with ethylene glycol or anti-freeze) causes loose stool and forces bowel contents through, rapidly reducing absorption. This is not routinely used.

• Forced diuresis for salicyclate poisoning is dangerous and should not be used.

• Urine alkalinisation is mainly used for salicylate overdose (see p. 403).

• Haemodialysis helps in severe salicylate poisoning, barbiturates, ethylene glycol, alcohol and lithium poisoning.

• Haemoperfusion involves passing heparinised blood across absorbents such as charcoal. Works for barbiturates and theophylline.

Antagonising the influences of poisons

• Acetylcysteine or methionine replenishes cellular glutathione stores in paracetamol poisoning.

• Ethanol is a competitive inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase and is given in ethylene glycol (anti-freeze) poisoning. Fomepizole is also useful when ethanol is contraindicated, e.g. previous excess alcohol user or liver disease.

Progress.

Benzodiazepine overdose

Benzodiazepines account for 40% of all overdoses.

Management – the problems

Respiratory depression or in combination with alcohol – vomiting and aspiration.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning

Case history (2)

On examination she was very thin and had a GCS of 10. There were no other physical signs.

Points to remember

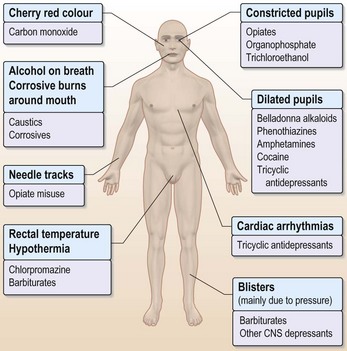

Physical examination (Fig. 13.1)

Management – the problems

Information

Important points:

• Severe liver or renal damage: seek specialist advice

• Contact liver unit if INR > 3.0 or alanine aminotransferase > 1000 U/L, evidence of acidosis, encephalopathy or hypotensive with systolic less than 60 mmHg

• Hypoglycaemia might develop in first 48 h

• Alert renal physicians if serum creatinine rises

• There is evidence that administration of acetylcysteine, even in patients with established hepatic encephalopathy, might improve the prognosis

How should you manage this patient?

For general management, see p. 396.

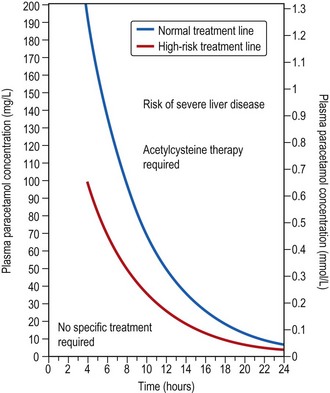

The treatment nomogram (Fig. 13.2)

• There are two lines on the nomogram: the normal and the high-risk treatment lines.

• The high-risk treatment line should be used for patients who are likely to be glutathione deplete, e.g. malnourished or HIV-positive patients.

• Alcohol dependent patients or those on enzyme inducers, e.g. phenytoin, rifampicin, carbamazepine, are also at high risk from lower levels of paracetamol.

• This patient’s prior eating disorder and low body weight indicate that the high-risk treatment line should be used to interpret the paracetamol levels.

What are the adverse reactions to acetylcysteine?

• Local itching and rashes at infusion sites.

• Systemic effects include nausea, flushing, angioedema, bronchospasm and hypotension. Treatment is with discontinuation of the infusion and an anti-histamine.

Intubation and ventilation were not required; pulse oximetry showed no impaired oxygenation.

Summary: how would you treat a paracetamol overdose?

If presentation within 8 h (as in this case)

• Gastric lavage or emesis up to 4 h post-ingestion.

• Use treatment nomogram at 4 h or later to guide use of acetylcysteine (see Fig. 13.2).

• If there is doubt about the timing, or if more than 12 g ingested, then treat with acetylcysteine immediately.

• If the 4-h paracetamol level is below the treatment line, discontinue acetylcysteine except in patients who are at high risk (see Fig. 13.2).

• If methionine or acetylcysteine is started within 8 h, the prognosis is good and patients can be considered for discharge at the end of the infusion if blood tests are normal.

• Prior to discharge check that INR and plasma creatinine are normal.

If a patient presents at 8–24 h post-ingestion

• Patients presenting more than 8 h post-ingestion are at greater risk of hepatotoxicity: the efficacy of treatment with acetylcysteine declines but still give it.

• Individual response to paracetamol overdose can be variable and the validity of the treatment line beyond 15 h post-ingestion is not clear.

• If there is doubt about the timing of overdose, or if more than 12 g have been consumed, then treat with acetylcysteine immediately.

• At the end of the infusion, check that the INR and plasma creatinine are normal. If so, risk of damage is negligible and discharge can be planned.

• If INR or creatinine is abnormal, or the patient develops symptoms, continue to monitor these blood tests till normal.

Salicylate overdose

• Aspirin is rapidly absorbed: usually peaks at 4 h.

• Beware modified-release formulations: these can prolong absorption.

Treatment

• Gastric lavage was not attempted as tablets taken 4 hours previously.

• Repeated doses of charcoal enhance elimination.

• Intravenous fluids with potassium supplements to correct dehydration, hypokalaemia and improve urine flow were given.

• Forced alkaline diuresis should not be used.

• Urine alkalinisation was used when plasma salicylate levels were found to be 620 mg/L. 8.4% bicarbonate (approx. 225 mL) in 1 h with careful monitoring.

• Haemodialysis should only be used when salicylate level is > 700 mg/L.

Tricyclic anti-depressant overdose

Clinical features

Treatment – supportive

• Gastric lavage up to 4 h post-ingestion for life-threatening amount of drug.

• Activated charcoal reduces absorption of tricylics; anti-cholinergic action delays gastric emptying.

• Cardiac monitor and watch for hypotension.

• Seizures might require IV diazepam 10 mg.

• Ventricular arrhythmias due to prolonged QT interval should not be treated with anti-arrhythmics but with under-drive or over-drive temporary pacing.

• Rarely, heart block and electrical mechanical dissociation have occurred.

• Occasionally, metabolic acidosis ensues – this should be corrected if pH of 7.0 or less develops using 1.4% sodium bicarbonate.

Cocaine

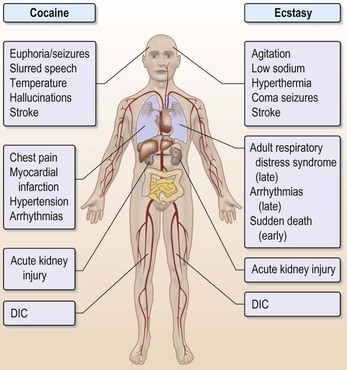

Cocaine (Fig. 13.3) can be inhaled (snorted), injected or swallowed or separated from its hydrochloride base and melted as crack. Binges with cocaine can last 24–96 h.

Clinical features of cocaine toxicity

• Euphoria, slurred speech, dilated pupils

• Pyrexia, sinus tachycardia and hallucinations (auditory, tactile and olfactory)

• Hypertension (may be severe) rarely causing haemorrhagic stroke, hyperventilation

• Myocardial infarction may occur in 6% of those with chest pain

• Ventricular arrhythmias, seizures

• Later kidney injury, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Ecstasy (see Fig. 13.3)

Clinical features

• Agitation, profound dehydration, low sodium due to excess water consumption or anti-diuretic hormone.

• Early arrhythmias (supraventricular or ventricular) occur and can cause sudden death.

• Nausea, vomiting, muscle pain, sinus tachycardia and visual hallucinations.

• Hypertension (might be severe) rarely causing haemorrhagic stroke, chest pain, hyperventilation.

• Hyperthermia, coma, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, rarely fulminant hepatic failure.

• Later: acute kidney injury, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Treatment – supportive

• Activated charcoal reduces absorption within 1 h.

• Early hyponatraemia due to excessive water consumption by Ecstasy users should be looked for before rehydration.

• Cardiac monitor and watch for hypertension.

• Treat agitation or seizures with IV diazepam 10 mg.

• Hyperthermia > 39°C can be reduced by 1 litre of cold saline. If temperature does not respond, IV dantrolene might help.

• Ventricular arrhythmias should be treated with anti-arrhythmics.

Gammahydroxybutyric acid (GHB)

Clinical features

• History might indicate no intent or knowledge of consumption of any drug.

• Initial euphoria, disinhibition, agitation, confusion, nausea and diarrhoea progressing within 1 h to drowsiness and unconciousness (potentiated by alcohol).

• Nausea, vomiting, muscle pain, sinus tachycardia, and rarely seizures.

• Bradycardia, respiratory depression and even Cheyne–Stokes respiration might rarely occur.

• Be alert to the possibility that such patients might have suffered sexual assault.

Treatment of GHB consumption – supportive

• Activated charcoal reduces absorption within 1 h: observe for a minimum of 2 h even if apparently clinically much improved.

• Monitor blood pressure, heart rate and pulse oximetry.

• Treat seizures with IV diazepam 10 mg.

• Bradycardia associated with hypotension should be treated with IV atropine.

Anaphylactic shock

Typically follows second or third challenge.

Immediate management

• Ensure clear airway and establish large-bore venous access.

• If there is serious hypoxia and stridor, tracheostomy might be required.

• Cardiovascular observations.

• Administer 0.5 mg adrenaline (epinephrine) intramuscularly (not IV) to create depot support for the circulation.

• Repeat after 5 min if still hypotensive.

Further management

• If persistent hypotension, infuse plasma expander e.g. 1 litre of Haemaccel.

• Salbutamol 2.5–5 mg nebulised or IV for bronchospasm or continued shock.

• An aminophylline infusion for continuing bronchospasm.

• Always identify precipitant.

• Advise on medic-alert bracelet.

• Provide the patient with adrenaline (epinephrine) Minijet 0.3 mg and tuition to inject in thigh in the event of exposure to allergen. This should be carried with the patient at all times.