Point of care testing

Outside the laboratory

Table 4.1 shows what can be commonly measured in a blood sample outside the normal laboratory setting. The most common blood test outside the laboratory is the determination of glucose concentration, in a finger stab sample, at home or in the clinic. Diabetic patients who need to monitor their blood glucose on a regular basis can do so at home or at work using one of many commercially available pocket-sized instruments.

Table 4.1

Common tests on blood performed away from the laboratory

| Analyte | Used when investigating |

| Blood gases | Acid–base status |

| Glucose | Diabetes mellitus |

| Urea | Renal disease |

| Creatinine | Renal disease |

| Bilirubin | Neonatal jaundice |

| Therapeutic drugs | Compliance or toxicity |

| Salicylate | Detection of poisoning |

| Paracetamol | Detection of poisoning |

| Cholesterol | Coronary heart disease risk |

| Alcohol | Fitness to drive/confusion, coma |

Figure 4.1 shows a portable bench analyser. These analysers may be used to monitor various analytes in blood and urine and are often used in outpatient clinics.

Table 4.2 lists urine constituents that can be commonly measured away from the laboratory. Many are conveniently measured, semi-quantitatively, using test strips which are dipped briefly into a fresh urine sample. Any excess urine is removed, and the result assessed after a specified time by comparing a colour change with a code on the side of the test strip container. The information obtained from such tests is of variable value to the tester, whether patient or clinician.

Table 4.2

Tests on urine performed away from the laboratory

| Analyte | Used when investigating |

| Ketones | Diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Protein | Renal disease |

| Red cells/haemoglobin | Renal disease |

| Bilirubin | Liver disease and jaundice |

| Urobilinogen | Jaundice/haemolysis |

| pH | Renal tubular acidosis |

| Glucose | Diabetes mellitus |

| Nitrites | Urinary tract infection |

| HCG | Pregnancy test |

The tests commonly performed away from the laboratory can be categorized as follows:

A Tests performed in medical or nursing settings. They clearly give valuable information and allow the practitioner to reassure the patient or family or initiate further investigations or treatment.

B Tests performed in the home, or non-clinical setting. They can give valuable information when properly and appropriately used.

C Alcohol tests. These are sometimes used to assess fitness to drive. In clinical practice alcohol measurements need to be carefully interpreted. In the Accident and Emergency setting, extreme caution must be taken before one can fully ascribe confusion in a patient with head injury to the effects of alcohol, a common complicating feature in such patients.

Methodology

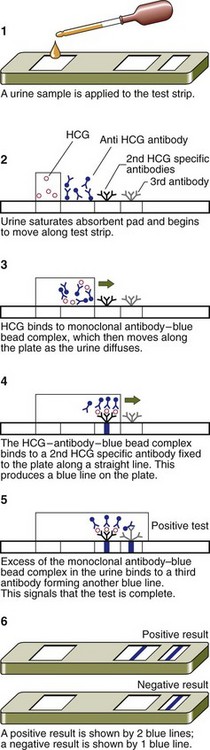

It is a feature of many sideroom tests that their simplicity disguises the use of sophisticated methodology. One type of home pregnancy test method involves an elegant application of monoclonal antibody technology to detect the human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), which is produced by the developing embryo (Fig 4.2). The test is simple to carry out; a few drops of urine are placed in the sample window, and the result is shown within 5 minutes. The addition of the urine solubilizes a monoclonal antibody for HCG, which is covalently bound to tiny blue beads. A second monoclonal antibody specific for another region of the HCG molecule, is firmly attached in a line at the result window. If HCG is present in the sample it is bound by the first antibody, forming a blue bead–antibody–HCG complex. As the urine diffuses through the strip, any HCG present becomes bound at the second antibody site and this concentrates the blue bead complex in a line – a positive result. A third antibody recognizes the constant region of the first antibody and binds the excess, thus providing a control to show that sufficient urine had been added to the test strip, the most likely form of error.

General problems

Cost. Many of these tests are expensive alternatives to the traditional methods used in the laboratory. This additional expense must be justified, for example, on the basis of convenience or speed of obtaining the result.

Cost. Many of these tests are expensive alternatives to the traditional methods used in the laboratory. This additional expense must be justified, for example, on the basis of convenience or speed of obtaining the result.

Responsibility. The person performing the assay outside the laboratory (the operator) must assume a number of responsibilities that would normally be those of the laboratory staff. There is the responsibility to perform the assay appropriately and to provide an answer that is accurate, precise and meaningful. The operator must also record the result, so that others may be able to find it (e.g. in the patient’s notes), and interpret the result in its clinical context.

Responsibility. The person performing the assay outside the laboratory (the operator) must assume a number of responsibilities that would normally be those of the laboratory staff. There is the responsibility to perform the assay appropriately and to provide an answer that is accurate, precise and meaningful. The operator must also record the result, so that others may be able to find it (e.g. in the patient’s notes), and interpret the result in its clinical context.