65 Pneumothorax and Other Chest Pathology

Ultrasound imaging can prevent and diagnose pneumothorax. Chest sonography is therefore an essential skill for those performing regional blocks. Regional anesthesia is the leading cause of pneumothorax during anesthesia, and twice as likely as the next leading cause.1 This is particularly surprising given that line placement is another potential cause of perioperative pneumothorax.

The incidence of pneumothorax after traditional supraclavicular block has been reported to be as high as 0.5% to 6%.2 This high incidence has led to concern that supraclavicular blocks should not be performed on outpatients. Pneumothorax after ultrasound-guided regional block has been reported.3

Several risk factors for pneumothorax and chest tube placement have been identified in patients undergoing interventional procedures.4 These include the needle traversing aerated lung or a lung fissure, lung hyperinflation from chronic obstructive lung disease, and positive-pressure ventilation.

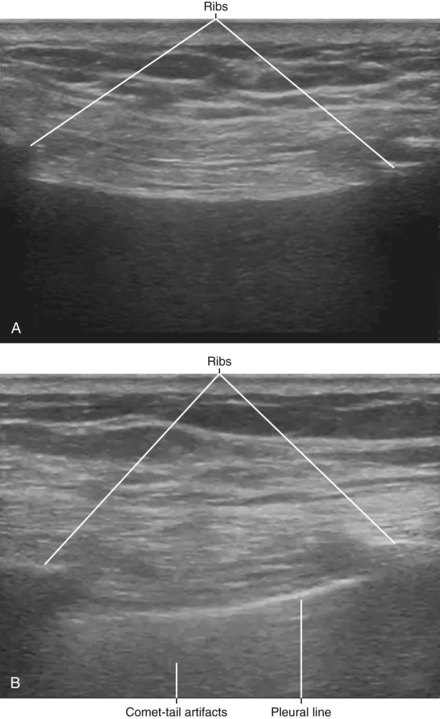

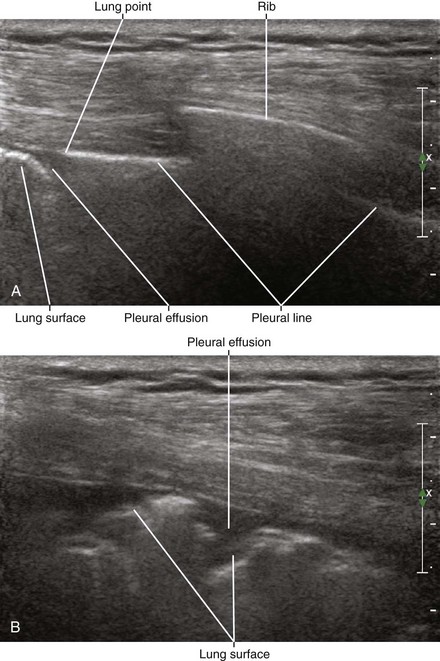

Because of the marked acoustic impedance mismatch with soft tissue, the pleura generates a brighter echo than the surface of the first rib. Comet-tail artifact can be observed deep to strongly reflecting structures, such as the lung.5,6 The comet-tail artifact usually manifests as dense, continuous echoes.

Lung sliding is the to-and-fro movement of the lung caused by respiration. Because most of the translational motion of ventilated lung is generated from descent of the diaphragm, lung sliding is smallest at the apex and maximal at the base. Therefore, lung sliding can be difficult to appreciate during supraclavicular views of the brachial plexus. In this location, the first rib and pleura are best distinguished by the absorption of ultrasound by the bone and comet-tail artifact that arises from the pleural line. The presence of lung sliding or comet-tail artifact rules out pneumothorax.7,8

1 Cheney FW, Posner KL, Caplan RA. Adverse respiratory events infrequently leading to malpractice suits: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:932–939.

2 Brown DL, Cahill DR, Bridenbaugh LD. Supraclavicular nerve block: anatomic analysis of a method to prevent pneumothorax. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:530–534.

3 Bryan NA, Swenson JD, Greis PE, et al. Indwelling interscalene catheter use in an outpatient setting for shoulder surgery: technique, efficacy, and complications. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:388–395.

4 Cox JE, Chiles C, McManus CM, et al. Transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy: variables that affect risk of pneumothorax. Radiology. 1999;212:165–168.

5 Ziskin MC, Thickman DI, Goldenberg NJ, et al. The comet tail artifact. J Ultrasound Med. 1982;1:1–7.

6 Thickman DI, Ziskin MC, Goldenberg NJ, et al. Clinical manifestations of the comet tail artifact. J Ultrasound Med. 1983;2:225–230.

7 Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill: lung sliding. Chest. 1995;108:1345–1348.

8 Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Biderman P, et al. The comet-tail artifact: an ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:383–388.

9 Reissig A, Kroegel C. Accuracy of transthoracic sonography in excluding post-interventional pneumothorax and hydropneumothorax: comparison to chest radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53:463–470.