Pneumonia

Perspective

Pneumonia is the seventh leading cause of death and the leading cause of death from infectious disease in the United States.1 The annual incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in the United States ranges from 2 to 4 million, resulting in approximately 500,000 hospital admissions. Most cases of CAP are managed in the outpatient setting and the mortality is low (approximately 1%), but pneumonia necessitating hospitalization is associated with a higher mortality rate (approximately 15%). Pneumonia remains challenging because of an expanding spectrum of pathogens, changing antibiotic resistance patterns, the continued introduction of newer antimicrobial agents, and increasing emphasis on cost-effectiveness and outpatient management.

Principles of Disease

Causative Agents

Difficulty in determining the specific cause of pneumonia exists even with advanced microbiologic and serologic testing that is not generally available during an ED evaluation. In CAP, a microbial cause cannot be determined in approximately half of cases, even after thorough investigation. Among hospitalized adults in whom a pathogen can be identified, organisms such as S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, referred to as “typical” pathogens, account for approximately half of cases. Legionella, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydophila (previously known as Chlamydia) species, referred to as “atypical” pathogens, are also common.2 Testing for common viral agents reveals a viral cause in approximately 18% of cases, with influenza and parainfluenza viruses being the most common.3

Among adults requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission, S. pneumoniae is the most common pathogen, with even higher prevalence among fatal cases. Legionella species, Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]), and aerobic gram-negative bacilli also appear to be relatively more common among adults with severe CAP.4 Atypical organisms, such as Mycoplasma species or viruses, account for a relatively higher proportion of pneumonia in patients who have milder illness that is amenable to outpatient therapy.5 Atypical organisms occur with significant frequency, however, in patients with severe illness requiring hospitalization, particularly because of Legionella infection. Coinfection, such as with Chlamydophila pneumoniae and S. pneumoniae, is also well recognized.

S. pneumoniae is a gram-positive coccus that is the most common cause of CAP in adults requiring hospitalization. It colonizes the nasopharynx in 40% of healthy adults. Although this organism can cause pneumonia in healthy people, patients with a history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, alcoholism, sickle cell disease, splenectomy, and malignancy or other immunosuppressive illness are at increased risk. A vaccine containing the 23 capsular polysaccharides of pneumococcal types most commonly associated with pneumonia reduces the likelihood of serious pneumococcal infection. It is recommended for people at increased risk because of underlying illness or age older than 65 years.6 Many ED patients have not received pneumococcal vaccine, and vaccinating eligible patients in this setting seems to be feasible and effective.7 A 13-valent protein-conjugate pneumococcal vaccine effectively reduces invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in infants and young children.8

S. aureus may be emerging as a more common cause of CAP and has been found more frequently than H. influenzae in some recent series. Community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) are uncommon in CAP but are more likely to cause severe disease.9 This is often associated with influenza. Staphylococcal pneumonias are often necrotizing, with cavitation and pneumatocele formation. Intravenous drug users may develop hematogenous spread of S. aureus that involves both lungs with multiple small infiltrates or abscesses (e.g., tricuspid endocarditis resulting in septic pulmonary emboli).

Viral pneumonias are common in infants and young children and are recognized as an important cause of pneumonia in adults. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza viruses are the most common causes of pneumonia in infants and small children, occurring mostly during autumn and winter. Influenza viruses are the most common cause of viral pneumonia in adults. Winter influenza outbreaks, usually of influenza type A, may cause 40,000 deaths annually in the United States. More than 90% occur in people age 65 years or older.10 Metapneumovirus is a paramyxovirus that seems to be an important cause of viral pneumonia in children and adults.

Clinical Features

Pneumonia generally manifests as a cough productive of purulent sputum, shortness of breath, and fever. In most healthy older children and adults, the diagnosis can be reasonably excluded on the basis of history and physical examination, with suspected cases confirmed by chest radiography. The absence of any abnormalities in vital signs or chest auscultation substantially reduces the likelihood of pneumonia as demonstrated by radiography. No single isolated clinical finding, however, is highly reliable in establishing or excluding a diagnosis of pneumonia.11

Patients in nursing homes or other extended-care facilities are at increased risk for infection with resistant organisms such as P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae (including strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases), Acinetobacter species, and hospital-associated strains of MRSA. Other risk factors for infection with multidrug-resistant pathogens include (1) hospitalization for 2 or more days in an acute care facility within 90 days of infection; (2) attendance at a hemodialysis clinic; and (3) intravenous antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, or wound care within 30 days of infection. Any patient with pneumonia in whom any one of these historical features is present, including patients from a nursing home or long-term care facility, is designated as having health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP). HCAP is associated with a greater likelihood of resistant pathogens such as Pseudomonas and MRSA, and mortality is higher than that for CAP.12

Diagnostic Strategies

Although many chest radiographs are obtained unnecessarily for patients with upper respiratory tract infections or bronchitis, it is difficult to identify a set of specific criteria to direct test ordering that is better than the clinical judgment of an experienced physician. A routine chest radiograph for all patients with cough is not necessary. Clinical judgment is more sensitive than suggestive findings (e.g., fever, tachycardia, oxygen desaturation, and an abnormal lung examination). Patients with serious underlying disease, severe sepsis, or shock and those in whom hospitalization is considered should undergo chest radiography. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting the presence of pulmonary consolidation, although the natural history of CT-positive, plain radiograph–negative pneumonia is not clear.13 Young, healthy adults with a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia who will be treated as outpatients may have a chest radiograph deferred unless there is a suspicion of immunocompromise or other unusual features of disease. A chest radiograph should be obtained subsequently if there is a poor initial response to treatment. Routine performance of chest radiography for patients with exacerbation of chronic bronchitis or COPD is of low yield and may be limited to patients with other signs of infection or congestive heart failure. Studies of infants with fever show that a routine chest radiograph is of low yield in the absence of other symptoms or signs of lower respiratory tract infection (e.g., abnormal auscultation or elevated respiratory rate).14

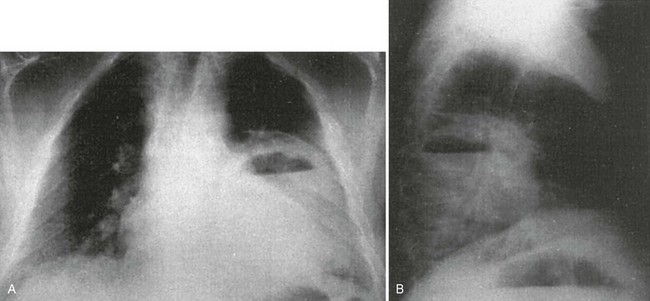

Although the causative agent cannot be determined solely by the results of chest radiography, certain radiographic patterns may suggest the possibility of specific pathogens. In pyogenic bacterial pneumonias, radiographs usually show an area of segmental or subsegmental infiltration and air bronchograms (Fig. 76-1). Lobar consolidation is present in a few cases of bacterial pneumonia, often caused by pneumococci or Klebsiella. A dense lobar infiltrate with a bulging fissure appearance on a chest radiograph is often described with pneumonia caused by Klebsiella, but this finding is nonspecific, and most cases manifest as a subtler bronchopneumonia. Pneumonia resulting from spread of infection along the intralobular airway results in fluffy or patchy infiltrates in the involved areas of the lung. A wide variety of bacteria and agents such as Chlamydophila species, Mycoplasma species, Legionella species, viruses, and fungi may cause this pattern.

An interstitial pattern on a chest radiograph (Fig. 76-2) typically is caused by Mycoplasma species, viruses, or P. jiroveci. The classic radiographic findings in PCP are bilateral interstitial infiltrates that begin in the perihilar region (Fig. 76-3). Radiographic manifestations of PCP can vary considerably, including normal appearance and lobar infiltrates, pleural effusions, hilar adenopathy, parenchymal nodules, and cavitary disease. Tiny nodules disseminated throughout both lungs represent a miliary pattern typical of granulomatous pneumonias, such as TB or fungal disease. The location of infiltrates may also give a clue to the cause. Aspiration pneumonia occurs in dependent areas of the lung, most commonly the superior segments of the lower lobes or posterior segments of the upper lobes. Infiltrates from pneumonias produced by hematogenous spread (e.g., S. aureus) tend to be multiple and peripheral. Apical infiltrates suggest TB.

The presence of additional radiographic features in association with infiltrates may suggest a specific cause. An infiltrate associated with hilar or mediastinal adenopathy suggests the presence of TB or fungal disease or may indicate pneumonia associated with a neoplasm. Bacteria most likely associated with cavitation (Fig. 76-4) are anaerobes, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and S. aureus. Cavitation also may be present in fungal disease or TB and with noninfectious processes (e.g., malignancy and pulmonary vascular disease). Pneumatoceles or spontaneous pneumothorax may be seen in AIDS patients with PCP. Pleural effusions occur with a wide variety of organisms, including many types of pyogenic bacterial pneumonias, Chlamydophila species, Legionella species, and TB. Anaerobic infections associated with an effusion are especially prone to development of empyema. The diagnosis and aspiration of pleural effusions can be aided by use of ED bedside ultrasonography.

Radiographic findings are nonspecific for predicting a particular infectious cause. Mycoplasma pneumonia may manifest as a dense infiltrate, or pneumococcal pneumonia may manifest as a diffuse interstitial infiltrate. Immunocompromised patients are particularly prone to having atypical radiographic appearances. Rarely, patients with a clinical picture strongly suggestive of pneumonia have a normal chest radiograph, and some are found to have an infiltrate within the next 24 to 48 hours. The absence of findings on a chest radiograph should not preclude the use of antimicrobial therapy in appropriate patients with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia.15 Laboratory studies also are nonspecific for identifying the cause of pneumonia. Although the finding of a white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 15,000/mm3 increases the probability of the patient having a pyogenic bacterial cause rather than a viral or atypical cause, the predictive value of this finding depends on the stage of the illness and likely prevalences of various causes. This is neither sensitive nor specific enough to aid decisions regarding therapy in an individual patient. A WBC count may be helpful if it yields evidence of immunosuppression, such as neutropenia, or if it reveals lymphopenia that may indicate immunosuppression from AIDS. Basic metabolic panels may help identify patients with renal or hepatic dysfunction or metabolic acidosis associated with sepsis. These findings predict a complicated course and influence decisions regarding disposition, choice of antimicrobial agents, and dosages. Serum lactate dehydrogenase is significantly elevated in AIDS patients with PCP compared with patients with non-PCP pneumonia. Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are not helpful in clinical decision-making regarding pneumonia. Procalcitonin level has been suggested as a means to assess likelihood of bacterial cause, response to antimicrobial therapy, and prognosis in pneumonia. Its utility in the ED to assess need for hospitalization or ICU admission compared with other risk-stratification systems (see later) has not been validated.16

Sputum Gram’s stain rarely results in a change in therapy or outcome. Correlation between identification of pneumococcus on Gram’s stain and sputum culture results is poor, even when commonly used criteria for an adequate sputum specimen (fewer than five squamous epithelial cells and more than 25 WBCs per high-power field) are applied. Gram’s stains are even less likely to show gram-negative pathogens, such as H. influenzae, and should not be relied on to rule out a gram-negative cause. Empirical antimicrobial agents are usually highly clinically effective if chosen based on clinical information without sputum analysis. Guidelines for management of CAP from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Thoracic Society (ATS) support limiting sputum Gram’s stain and culture to those patients with more severe disease or risk factors for unusual pathogens.1 Confirmation of the diagnosis of PCP requires sputum induction and staining and, in some cases, further invasive procedures, such as bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage or biopsy.

Routine blood cultures are of essentially no value in nonimmunocompromised adults with pneumonia, in whom there is a very low prevalence of bacteremia, and management is rarely changed based on the results.17,18 Follow-up of false-positive blood cultures is costly and labor-intensive and may lead to unnecessary use of antibiotics such as vancomycin or linezolid when contaminant growth is initially reported as gram-positive cocci. Blood cultures should be obtained from immunocompromised patients, those with severe sepsis or shock, or those with risk factors for endovascular infection (e.g., prosthetic valves, intravenous drug use, or cavitary infiltrates).1 When culture specimens are drawn, they should be obtained before the initiation of antibiotics (although antibiotics should not be delayed for this reason).

Patients with a pleural effusion greater than 5 cm on lateral upright posterior-anterior chest radiograph should undergo diagnostic thoracentesis,1 with fluid sent for cell count, differential, pH (pH below 7.2 predicts the need for a thoracostomy tube), Gram’s stain, and culture. For most patients, thoracentesis can be safely deferred until after hospital admission. Patients in significant respiratory distress, however, or with evidence of tension and mediastinal shift require emergent diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis.

Serologic tests are available for the diagnosis of many organisms, including C. pneumoniae, Legionella species, and fungi. The use of serologic tests to determine the cause of pneumonia may be helpful retrospectively, but they usually require acute and convalescent serum titers and are of little use in the ED. Urine antigen tests for S. pneumoniae and Legionella are available, and in some facilities results can be obtained within the time frame of an ED evaluation. It is not clear, however, that a positive result should prompt a change in empirical treatment.1 Rapid diagnostic tests for viral antigens are available for several viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza. These tests may be useful for infection control decisions in hospitalized patients, and they may provide an indication for influenza therapy and family prophylaxis. Some commercially available rapid influenza tests are insensitive for certain strains, notably the 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain. Rapid testing for respiratory viruses (i.e., RSV, influenza A including the H1 subtype, influenza B, metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and entero-rhinovirus) with use of technology such as the polymerase chain reaction may become increasingly available to emergency physicians to determine the specific cause of pneumonia.

Differential Diagnosis Considerations

Aspiration

Acute aspiration of acidic fluid into the lungs may produce fever, leukocytosis, purulent sputum, and radiographic infiltrates that mimic bacterial pneumonia. Although many such patients go on to develop bacterial pneumonia, prophylactic administration of antibiotics is controversial.19 Antibiotics should be initiated if the patient develops signs of bacterial pneumonia, including new fever, expanding infiltrate appearing more than 36 hours after aspiration, or unexplained deterioration. Systemic corticosteroids for acute aspiration are of no benefit.

Management

The possibility of communicable disease should suggest early isolation.20 Patients with a history of TB exposure or suggestive symptoms (e.g., persistent cough, weight loss, night sweats, and hemoptysis) or who belong to a group at high risk for TB (e.g., homeless, intravenous drug user, alcoholic, HIV risk, and immigrant from high-risk area) should be given a mask and placed in respiratory isolation before evaluation, including chest radiography.21 Because AIDS patients with pulmonary TB cannot be distinguished reliably from AIDS patients with other pulmonary infections at presentation, TB should be considered in all HIV-infected patients with respiratory complaints, and respiratory isolation should be initiated. EDs that frequently care for patients at risk for TB should consider triage protocols to identify these individuals rapidly before patients, visitors, or staff are unnecessarily exposed. Suspected infection with organisms transmitted by respiratory droplet (e.g., influenza) should prompt infection control precautions such as a mask being placed on the patient.

Antimicrobials should be administered in the ED for patients who are being admitted to the hospital. Timely administration of antimicrobials is associated with improved outcomes for hospitalized pneumonia patients,22 although confounding factors limit a full understanding of this relationship. A rush to treatment without a diagnosis of pneumonia, however, can result in inappropriate antibiotic use. Although the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have used specific time cutoffs for blood culture and antibiotic administration as a quality measure, the evidence that antibiotic delay on the order of hours is significantly deleterious is weak, and the IDSA/ATS guidelines for management of pneumonia do not recommend use of a specific time threshold. Any presumed benefit of early antibiotic administration should be weighed against the risk of inappropriate use for cases in which the diagnosis is unclear. The antibiotics selected should cover the likely causes based on clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and epidemiologic information. The regimen should also be as selective as possible to avoid drug toxicity, emergence of resistance to broad-spectrum agents, and excessive cost.

CA-MRSA is the most common pathogen isolated in community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections. It causes severe, rapidly progressing pneumonia with sepsis, often in children or healthy young adults with influenza.23 CA-MRSA remains an uncommon cause of CAP in the United States,9 but empirical coverage of MRSA should be strongly considered for patients with severe pneumonia associated with sepsis,24 especially those with a presumed influenza infection, contact with someone infected with MRSA, or radiographic evidence of necrotizing pneumonia. Antimicrobials with consistent in vitro activity against CA-MRSA isolates include vancomycin, TMP-SMX, daptomycin, tigecycline, linezolid, and ceftaroline. Although vancomycin is used most often for documented MRSA infections, vancomycin may be losing efficacy in light of increasing minimum inhibitory concentrations. Daptomycin is inactivated by pulmonary surfactant and consequently is not indicated for pneumonia.

Appropriate agents for outpatient treatment of adults with CAP include macrolides, doxycycline, and fluoroquinolones with enhanced activity against S. pneumoniae (Table 76-1).1 In patients properly identified as being at low risk for complications with careful outpatient follow-up, use of a macrolide such as azithromycin 500 mg orally (PO) once, followed by 250 mg PO daily for 4 days, is preferred. Doxycycline is an alternative choice that has activity against some uncommon causes of pneumonia such as MRSA, but it has more side effects. For patients at higher risk of DRSP owing to recent antibiotic use or comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease, a respiratory fluoroquinolone should be considered. For patients who have received a fluoroquinolone within the previous few months, a combination of a macrolide plus a β-lactam agent (e.g., high-dose amoxicillin [1 g three times daily], amoxicillin-clavulanate [2 g PO twice daily], or cefpodoxime) is appropriate. For school-age children and adolescents, amoxicillin is an appropriate first-line agent, and azithromycin can be used for those with findings suggestive of Mycoplasma pneumonia.25

Table 76-1

Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Older Children and Adults: Outpatient Treatment

| CLINICAL SETTING | ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN* | COMMENTS |

| Previously healthy, no antimicrobials in last 3 mo | Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid | Preferred for adolescent or young adult when likelihood of Mycoplasma is high; variable activity vs. Streptococcus pneumoniae. |

| Azithromycin 500 mg once, followed by 250 mg daily for 4 days | Treats common typical bacterial and atypical pathogens. Clarithromycin can be substituted. | |

| Comorbidities, or antimicrobials in last 3 mo | Levofloxacin 750 mg PO daily for 5 days | Can substitute moxifloxacin 400 mg daily for 7-14 days. Treats common typical and atypical bacterial pathogens; active vs. DRSP. Use fluoroquinolone if recently received β-lactam or macrolide. |

| Cefpodoxime 200 mg PO bid + azithromycin 500 mg PO daily | Use if fluoroquinolones recently received. Can substitute cefdinir, cefprozil, or amoxicillin-clavulanate for cefpodoxime. Variable activity against DRSP. |

DRSP, drug-resistant S. pneumoniae; PO, orally.

*Doses are for 70-kg adult with normal renal and hepatic function.

For patients whose illness is severe enough to necessitate hospital admission and parenteral antibiotics, a combination of a β-lactam agent, such as ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously (IV) q24h (or ceftaroline, cefotaxime, ampicillin-sulbactam, or ertapenem), plus a macrolide (e.g., intravenous or oral azithromycin 500 mg daily) is the preferred regimen. Alternatively, an extended-spectrum fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) can be given as monotherapy, but this regimen may be more likely to promote antimicrobial resistance. Fluoroquinolones have some activity against TB and should be avoided in patients for whom TB is a possible cause, owing to risk of obscuring the correct diagnosis and selection of resistant TB. These regimens treat the most common bacterial pathogens, such as S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae, and atypical pathogens, such as Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila, and Legionella species A regimen with activity against atypical pathogens is recommended by IDSA/ATS guidelines, but studies do not clearly demonstrate better outcomes in hospitalized patients compared with regimens without atypical activity.26 Intravenous azithromycin alone may be an option for patients with milder illness who are unlikely to be bacteremic; it does not achieve significant serum levels and lacks significant activity against many aerobic gram-negative bacilli and DRSP. If anaerobic organisms are suspected (e.g., aspiration), clindamycin or metronidazole could be added to the regimen, or the regimen could include an antibiotic with anaerobic activity, such as ertapenem, ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, tigecycline, or moxifloxacin (Table 76-2).

Table 76-2

Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Older Children and Adults: Inpatient Antimicrobial Treatment

| CLINICAL SETTING | ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN* | COMMENTS |

| Community-acquired, nonimmunocompromised | Ceftriaxone 1 g q24h + azithromycin 500 mg q24h IV or PO | Can substitute cefotaxime, ceftaroline, ampicillin-sulbactam, or ertapenem for ceftriaxone. |

| Respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg IV q24h or moxifloxacin 400 mg IV q24h) | Treats most common bacterial and atypical pathogens. Active vs. DRSP. | |

| Severe pneumonia (ICU) | Ceftriaxone 1 g IV q24h + levofloxacin 750 mg IV q24h + vancomycin 1 g IV q12h | Can substitute cefotaxime, cefepime, ceftaroline, ertapenem, or β-lactam or β-lactamase inhibitor for ceftriaxone. Can substitute moxifloxacin for levofloxacin. Can substitute linezolid for vancomycin. |

| Health care–associated pneumonia or severe pneumonia with neutropenia, bronchiectasis (risk for Pseudomonas) | Cefepime 2g IV q12h + ciprofloxacin 500 mg IV q12h + vancomycin 1 g IV q12h | Can substitute other antipseudomonal β-lactam, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem, meropenem, or doripenem, for cefepime. Can substitute aminoglycoside plus macrolide for ciprofloxacin. |

| Presumed PCP | TMP-SMX 240/1200 mg IV q6h | Add ceftriaxone to TMP-SMX if severe, until PCP confirmed. Alternatives for sulfa allergy include clindamycin + primaquine. |

*Doses are for a 70-kg adult with normal renal and hepatic function.

Seriously ill patients with severe sepsis or septic shock require aggressive fluid resuscitation and may benefit from more intensive management with vasopressors, transfusion, and inotropic agents as part of early goal-directed therapy.27 Severely ill and compromised patients are at relatively greater risk of infection with S. pneumoniae, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, S. aureus (including MRSA), and, in some areas, Legionella species. For pneumonia patients admitted to an ICU, adequate activity against DRSP may be more important. Outcomes with severe pneumonia may be better with combination therapy.28 A third-generation cephalosporin or β-lactam or β-lactamase inhibitor can be combined with a macrolide or fluoroquinolone, and addition of vancomycin or linezolid should be considered for MRSA activity. Addition of an aminoglycoside could be considered if septic shock is present.

Because HCAP is associated with higher mortality and a greater likelihood of unusual pathogens, the use of broader-spectrum empirical therapy is appropriate, usually with a combination of antimicrobials to increase the chance that at least one antibiotic will be active against the causative pathogen. Appropriate combinations include an antipseudomonal β-lactam agent, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, imipenem, or meropenem, with either an aminoglycoside or a fluoroquinolone and vancomycin or linezolid for MRSA.29

For patients with AIDS, it is important to treat P. jiroveci and bacterial pathogens such as S. pneumoniae. TMP-SMX is the treatment of choice; the usual regimen is 15 mg/kg of TMP and 75 mg/kg of SMX daily in four divided doses, to be continued for 21 days, in addition to a regimen to cover CAP organisms.30 For most adult patients a regimen of three ampules (80 mg of TMP and 400 mg of SMX per ampule) every 6 hours is appropriate. For patients allergic to sulfa, options include clindamycin 600 mg IV every 8 hours plus primaquine 30 mg PO daily. The addition of corticosteroids (prednisone 40 mg PO twice daily) reduces mortality and clinical deterioration in patients with partial arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) less than 70 mm Hg or alveolar-arterial gradient greater than 35 mm Hg. Mycoplasma, Legionella, and Chlamydophila species are uncommon causes of severe pneumonia in AIDS patients, so empirical therapy with erythromycin or doxycycline is not routinely recommended.

Patients with influenza may benefit from antiviral treatment as described in Chapter 130.

Disposition

There is tremendous variability in physician admission decisions for pneumonia.31 The more common tendency is overestimation of disease severity, leading to hospitalization of patients at low risk for death or serious complications. The decision to hospitalize a patient with pneumonia does not necessarily mean that a prolonged inpatient stay is required. Observation for 12 to 24 hours in the ED observation unit or hospital may allow the early discharge of certain moderate-risk patients. Inpatient treatment of pneumonia is 15 to 20 times more expensive per patient than outpatient treatment, and most patients are more comfortable in a home environment.

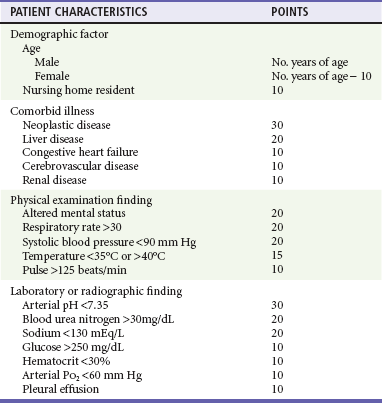

Although no firm guidelines exist regarding hospital admission, scoring systems may assist with hospitalization decisions. One commonly used system is based on the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team study, a prospectively validated predictive rule for mortality among immunocompetent adults with CAP.32 This model (also known as the Pneumonia Severity Index [PSI]) suggests a two-step approach to assess risk. Patients in the lowest risk class who are recommended for outpatient management are those younger than 50 years, without significant comorbid conditions (neoplasm, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, liver disease, or HIV), and without the following findings on physical examination: altered mental status, pulse 125 beats/min or greater, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min or greater, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, or temperature less than 35° C or 40° C or greater. Patients who do not fit the lowest risk category are classified into categories based on a scoring system that accounts for age, comorbid illness, physical examination findings, and laboratory abnormalities (Table 76-3). Hospitalization is recommended for patients with a score greater than 91, and brief admission or observation may be considered for patients with a score of 71 to 90. Although this method of assessing the likelihood of successful outpatient management is helpful, it can be cumbersome, is not modeled to predict acute life-threatening events, does not take into account dynamic evaluation over time, and has many important exceptions (e.g., an otherwise low-risk patient with severe hypoxia would be discharged by strict interpretation of this rule). Clinical judgment should supersede a strict interpretation of this scoring system. A study in which physicians were educated, however, and provided the patient’s risk score revealed a significantly lower overall admission rate, cost savings, and similar quality-of-life scores compared with those for patients conventionally managed by their physicians.33 Additional discharge criteria include improving and stable vital signs over a several-hour observation period, ability to take oral medications, an ambulatory pulse oximetry greater than 90%, home support, and access to follow-up.

Table 76-3

Scoring System for Pneumonia Mortality Prediction

Adapted from Mandell LA, et al: Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis 37:1405, 2003.

A simpler tool is the CURB-65 rule.34 This rule uses only five simple criteria to determine patients at lower risk for adverse events: confusion, uremia (blood urea nitrogen >20 mg/dL), respiratory rate greater than 30, blood pressure less than 90 systolic or less than 60 diastolic, and age 65 years or greater. The risk of 30-day mortality increases with a greater number of these factors present: 0.7% with zero factors, 9.2% with two factors, and 57% with five factors. Patients with zero or one feature can receive outpatient care, those with two should be admitted, and ICU care should be considered for those with three or more. No randomized trials of hospital admission strategies directly compare the PSI with the CURB-65 score. In a comparison of scores in the same population of CAP patients, the PSI yields a slightly higher percentage of patients in the low-risk category, with a similar low mortality rate.35

The decision to admit a patient to the ICU is straightforward when patients are intubated or require vasopressors. It is more difficult to identify patients who do not require these interventions initially but may be at greater risk for deterioration and require a level of monitoring that may be beyond that available on the typical hospital ward. Objective criteria using the PSI (class V) and CURB-65 have been proposed but are not prospectively validated for the ICU admission decision.36 When similar criteria were retrospectively studied in a cohort of CAP patients, they did not perform better than actual physician decisions.37 IDSA/ATS guidelines include criteria for defining severe CAP (Box 76-1), but these have not been validated.1 An ICU risk-stratification score is abbreviated SMART COP; intensive respiratory or vasodepressor support is predicted by low systolic blood pressure (2 points), multilobar chest radiography involvement (1 point), low albumin level (1 point), high respiratory rate (1 point), tachycardia (1 point), confusion (1 point), poor oxygenation (2 points), and low arterial pH (2 points). A SMART-COP score above 3 points identified 92% of patients who received intensive respiratory or vasodepressor support, including 84% of patients who did not need immediate admission to the ICU.38 The decision to admit a patient to the hospital largely reflects the potential for acute deterioration, and some rate of floor to ICU transfer is inevitable.

References

1. Mandell, LA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S27.

2. Johansson, N, Kalin, M, Tiveljung-Lindell, A, Giske, CG, Hedlund, J. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: Increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:202.

3. de Roux, A, et al. Viral community-acquired pneumonia in nonimmunocompromised adults. Chest. 2004;125:1343.

4. Rello, J, et al. Microbiological testing and outcome of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;123:174.

5. Marrie, TJ, Poulin-Costello, M, Beecroft, MD, Herman-Gnjidic, Z. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia treated in an ambulatory setting. Respir Med. 2005;99:60.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult Immunization Schedule. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html.

7. Rudis, MI, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department: An assessment of need. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:386.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Birth-18 Years & “Catch-up” Immunization Schedules. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html.

9. Moran, GJ, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as an etiology of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1126.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Season Influenza Information for Health Professionals. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/index.htm.

11. Metlay, JP, Kapoor, WN, Fine, MJ. Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? JAMA. 1997;278:1440.

12. Kollef, MH, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: Results from a large U.S. database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128:3854.

13. Lähde, S, Jartti, A, Broas, M, Koivisto, M, Syrjälä, H. HRCT findings in the lungs of primary care patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:159–163.

14. Frederick, RC. The clinical diagnosis of infantile pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:627.

15. Basi, SK, Marrie, TJ, Huang, JQ, Majumdar, SR. Patients admitted to hospital with suspected pneumonia and normal chest radiographs: Epidemiology, microbiology, and outcomes. Am J Med. 2004;117:305–311.

16. Huang, DT, et al. Risk prediction with procalcitonin and clinical rules in community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:48–58.

17. Kennedy, M, et al. Do emergency department blood cultures change practice in patients with pneumonia? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:393.

18. Moran, GJ, Abrahamian, FM. Blood cultures for pneumonia: Can we hit the target without a shotgun? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:407.

19. Raghavendran, K, Nemzek, J, Napolitano, LM, Knight, PR. Aspiration-induced lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:818–826.

20. Rothman, RE, et al. Respiratory hygiene in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:570.

21. Jensen, PA, Lambert, LA, Iademarco, MF, Ridzon, R. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-17):1.

22. Houck, PM, Bratzler, DW, Nsa, W, Ma, A, Bartlett, JG. Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:637.

23. Moran, GJ, Talan, DA. MRSA community-acquired pneumonia: Should we be worried? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:366–368.

24. Liu, C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e181.

25. Bradley, JS, et al. Executive summary: The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: Clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:617–630.

26. Shefet, D, Robenshtock, E, Paul, M, Leibovici, L. Empiric antibiotic coverage of atypical pathogens for community acquired pneumonia in hospitalized adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2005.

27. Nguyen, HB, et al. Severe sepsis and septic shock: Review of the literature and emergency department management guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:28.

28. Martin-Loeches, I, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy with macrolides improves survival in intubated patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:612.

29. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388.

30. Thomas, CF, Limper, AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487.

31. Dean, NC, et al. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: Variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:35.

32. Fine, MJ, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243.

33. Marrie, TJ, et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2000;283:749.

34. Lim, WS, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: An international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377.

35. Aujesky, D, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384.

36. Moran, GJ, Talan, DA, Abrahamian, FM. Diagnosis and management of pneumonia in the emergency department. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:53.

37. Angus, DC, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: Use of intensive care services and evaluation of American and British Thoracic Society Diagnostic criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:717.

38. Charles, PG, et al. SMART-COP: A tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:375–384.