CHAPTER 4 Plica Synovialis of the Elbow

Documentation of synovial plica as an anatomic structure began in 1912, when Testut described the “humeral radialis labrum.”1,2 Descriptions of this as a pathologic condition began in the 1950s.3–5 Since then, the pathologic condition has been described as the lateral synovial fringe,6 snapping plica,7 and synovial fold of the humeral radial joint.1 Identification of the plica as a pathologic condition can be traced to individual case reports within the past 30 years that described symptoms, clinical presentation, and treatment. The true significance has been dramatically enhanced with the advent of arthroscopy.

ANATOMY

Most of the early and recent anatomic descriptions of this structure come from the Japanese or French literature.8–12 One of the most detailed accounts was provided by Isogai and colleagues.10 Anterior and posterior folds have been documented in embryo and adult elbows, confirming these folds as normal anatomic structures (Fig. 4-1).13 The so-called lateral fold has been identified only in adults.10 This finding prompted the theory that a single event, repetitive trauma, or anatomic variant combined with activity may give rise to the development of the pathologic structure. This theory is enhanced by recognition that the histology of the normal anterior and posterior folds is that of fibrous fatty tissue; however, the lateral plica consists of hyaluronized bundles with fibrous tissue, making it histologically different from the anterior and posterior bands.10 Others have recognized that histologically, normal plica reveals uninflamed fibrofatty synovial tissue with no evidence of necrosis.1 However, a hard, fibrous type of tissue is characteristic of the lateral or circumferential variation of the plica.

Duparc and coworkers1 performed careful dissections on 50 elbows and demonstrated some form of a synovial fold in 43 (86%). They described six orientations, including four (9%) that were circumferential. In 30, the structure was described as rigid, and in the remaining 13, it was soft and pliable. The relationship with degenerative changes of the radial head was also recognized. A later German investigation sought to define the accuracy of MRI detection of the plica. These investigators determined that MRI detected some form of a plica in 88 studies. Dividing the folds into small (31%), medium (57%), and large (12%), they also correlated degenerative changes with the larger plicae.14

PATIENT EVALUATION

Early recognition of the potential pathologic features of this tissue has been offered in case reports.9 Circumferential synovial flow was found to roll over the radial head and then slide back over the radial neck with extension and flexion, respectively.6 Duparc and collagues1 also recognized that 4 of 43 folds were actually circumferential and seemed to blend with the annular ligament and the margin of the radial head. It is this particular variant that appears to be the pathologic lesion (see Fig. 4-1).

Clinical Presentation

In the early descriptions, the pain was confused with that of tennis elbow. It might have been confusion with this lesion that prompted the so-called Bosworth approach to tennis elbow.15 In this procedure, arthrotomy and inspection of the joint was recommended because it was recognized that intra-articular changes correlated to lateral elbow pain. Numerous investigators have subsequently pointed out the difficulty of differentiating a pathologic plica from lateral epicondylitis when the characteristic snapping is absent.1,6,16 The diagnosis becomes simplified when the clinical presentation is not so much lateral or posterolateral joint pain, but rather catching, snapping, and locking. The differential diagnosis may be tennis elbow or a loose body, depending on the presence or absence of the mechanical features.6,7

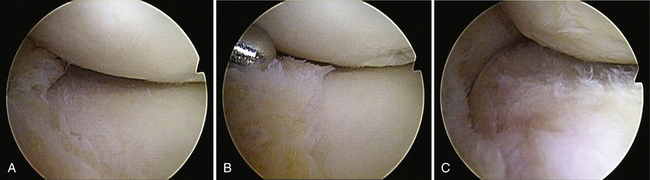

Early descriptions found this entity to be sufficiently and interestingly uncommon to be the source of case reports.3,6,8,9,12 They characterized the pathologic tissue as enveloping the radial head in extension. These early observations also recognized the coexistence of chondromalacia of the margin of the radial head. Isogai and coworkers10 carefully assessed the size, shape, and location and correlated these observations with pathologic changes. The lateral or circumferential component of the complex is considered to be the pathologic anatomy that is associated with the clinical syndrome. The anterior and posterior bundles are considered to be normal variants. The gross anatomy of the pathologic version is that of a prominent intraarticular band that parallels the annual ligament: the intra-articular fold slips over the radial head in extension of less than 90 degrees and then slides over the radial neck with flexion beyond 90 to 100 degrees.6,7 This translation results in a well-recognized chondromalacia of the margin of the radial head. Others16 have speculated that there is an association of this lesion and subtle posterolateral rotatory instability.10,16 However, this relationship is poorly understood.

Diagnosis

The patient typically presents with chronic, repetitive injury or a single traumatic episode. The most common and obvious presentation is snapping or catching of the elbow, which occurs at about 90 to 100 degrees of flexion and is exacerbated by pronation.6,7,11 The patient may experience aching over the lateral epicondyle. This pattern is responsible for confusion with lateral epicondylitis. Because MRI can identify a fold in most patients, it is not very specific.14 The diagnosis is usually made clinically and confirmed arthroscopically.

TREATMENT

Indications

Treatment of this lesion is straightforward. It is especially suited for arthroscopic intervention.

Technique

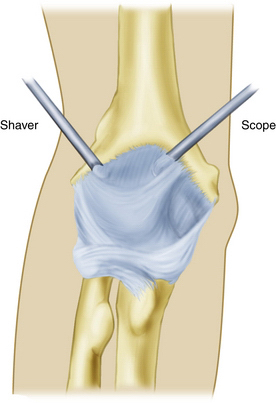

The patient is positioned according to the surgeon’s preference. An anteromedial portal is commonly used (Fig. 4-2), although some prefer a midlateral observation portal. The plica is usually readily seen around the head when the elbow is extended past 60 degrees and slides over the head and around the neck with flexion beyond 90 to 100 degrees. Observing the altered position of the plica with flexion and extension provides absolute confirmation of the diagnosis.

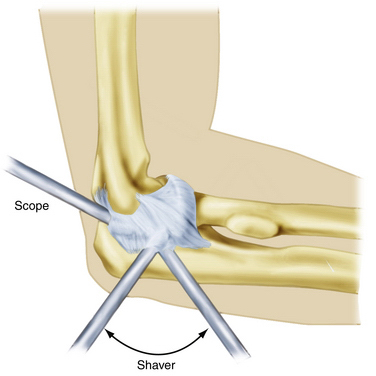

Removing the plica is all that is required to relieve the symptoms, and additional lateral portals may be used (Fig. 4-3). Davis and coworkers17 described the use and value of dual direct lateral portals and found they afforded excellent visualization for osteochondritis dissecans and lateral elbow plica.

FIGURE 4-3 Dual midlateral portals may be necessary for the scope and shaver to adequately reseat the plica.

(Courtesy of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Rochester, MN.)

OUTCOMES

Several studies have had relatively large sample sizes of 10 to 14 patients.7,11,16 These investigators universally demonstrated a high likelihood of success with arthroscopic resection; more than 90% of patients were free of all symptoms within a short postoperative surveillance period. There was minimal postoperative morbidity. However, Antuna and O’Driscoll did observe that 2 (15%) of 14 patients had some residual discomfort, and 1 patient developed recurrence of the snapping several months after resolution of symptoms postoperatively. The articular changes that frequently occur at the radial head may become symptomatic in the future (Fig. 4-4).

COMPLICATIONS

The most likely complication is development of instability from an aggressive capsular release of the plica that violates the lateral ulnar collateral ligament. This situation causes posterior lateral rotatory instability.

1. Duparc F, Putz R, Michot C, Muller JM. The synovial fold of the humeroradial joint: anatomical and histological features, and clinical relevance in lateral epicondylalgia of the elbow. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002;24:302-307.

2. Testut L. Traite’ d’Anatomie Humaine. Paris, France: Doin,; 1928.

3. Miyazaki K, Murakami H. Report of a case of snapping elbow. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1958;32:250-254.

4. Paturet G. Membres Superieur et Inferieur. Vol. II, Traite d’Anatomic Humaine. Paris, France: Masson; 1951.

5. Wightman JAK. Clicking elbow from a torn annular ligament: report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963;45B:380-381.

6. Clarke RP. Symptomatic, lateral synovial fringe (plica) of the elbow joint. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:112-116.

7. Antuna SA, O’Driscoll SW. Snapping plicae associated with radiocapitellar chondromalacia. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:491-495.

8. Akagi M, Nakamura T. Snapping elbow caused by the synovial fold in the radiohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:427-429.

9. Commandre FA, Taillan B, Benezis C, et al. Plica synovialis (synovial fold) of the elbow: report of one case. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1988;28:209-210.

10. Isogai S, Murakami G, Wada T, Ishii S. Which morphologies of synovial folds result from degeneration and/or aging of the radiohumeral joint? An anatomic study with cadavers and embryos. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:169-181.

11. Kim DH, Gambardella RA, Elattrache NS, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of posterolateral elbow impingement from lateral synovial plicae in throwing athletes and golfers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:438-444.

12. Kurosawa H, Koide S, Yaoita T, Nakajima H. Snapping elbow caused by the plica synovialis patellaris. Rinsyo Seikei Geka. 1976;11:231-237.

13. Llusá Pérez M, Ballesteros BetancourtJR, Forcada Calvet P, Carrera Burgaya A. Atlas de discción Anatomoquirúrgica del Codo. Barcelona, Spain: Elsevier Masson; 2009.

14. Vahlensieck M, Wiche U, Schmidt HM. Humeroradial plica: frequency and visualization on MRI. Rofo. 2004;176:959-964.

15. Bosworth D. The role of the orbicular ligament in tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37A:527.

16. Ruch DS, Papadonikolakis A, Campolattaro RM. The posterolateral plica: a cause of refractory lateral elbow pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:367-370.

17. Davis JT, Idjadi JA, Siskosky MJ, ElAttrache NS. Dual direct lateral portals for treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:723-728.