52 Platelet Disorders

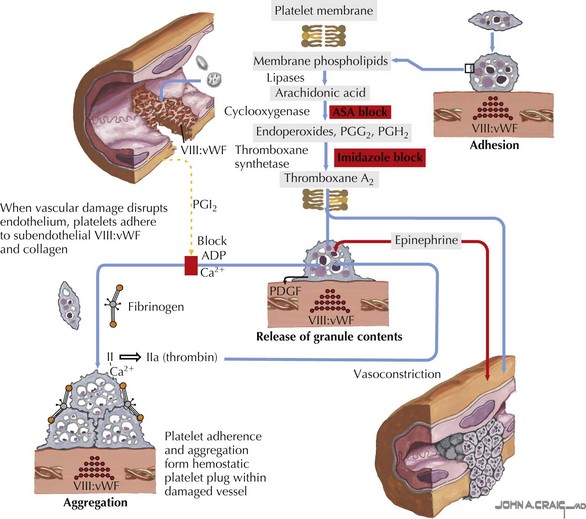

Platelets are small anucleate cell particles (5-7 µL in volume) that play a critical role in primary hemostasis. At the time of vascular injury, platelets rush to the site of vascular damage and adhere to the exposed collagen, forming a temporary platelet plug to prevent continued bleeding. The platelets are then activated and undergo changes in their shape and structure. These changes allow the platelets to bind to fibrinogen and aggregate with one another, thus propagating the platelet plug. Activation of platelets also causes secretion of the chemicals contained in the platelet storage granules. These chemicals recruit new platelets and contain many compounds needed to continue primary hemostasis and activate secondary hemostasis (Figure 52-1).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Acquired Platelet Disorders

Acquired platelet disorders are far more common than congenital platelet disorders. The most common reason for acquired thrombocytopenia or an acquired platelet abnormality is drug exposure. Dozens of medications can cause thrombocytopenia or abnormalities in platelet function. These medications can act by inhibiting bone marrow production of platelets or activating or creating antibodies to platelets, or they can have a direct toxic effect on platelets. Refer to Table 52-1 for a list of some of the common medications resulting in thrombocytopenia and platelet function abnormalities. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a special case and is discussed again later this chapter.

Table 52-1 Common Medications Resulting in Thrombocytopenia or Platelet Function Abnormalities

| Drugs Associated with Thrombocytopenia | Drugs Associated with Abnormal Platelet Function |

|---|---|

GI, gastrointestinal; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

Clinical Presentation And Differential Diagnosis

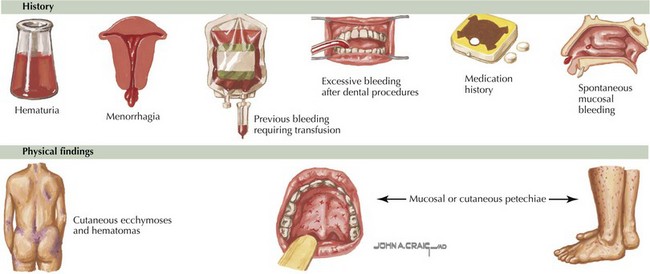

The clinical presentation of platelet disorders varies with the platelet count or the severity of the platelet function abnormality. The clinical picture of a patient with a platelet disorder is that of mucocutaneous bleeding. The patient may have epistaxis, easy bruising, petechiae, menorrhagia, or gingival bleeding. More significant mucocutaneous bleeding can be seen with a very low platelet count (<20,000/µL) or in disorders with severe platelet dysfunction. This may consist of gastrointestinal bleeding or hematuria. With extremely low platelet counts (<10,000/µL), there is a risk of spontaneous bleeding and an increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage. This is particularly of concern in NAIT (Figure 52-2). Some children may be asymptomatic but develop excessive bleeding with significant hemostatic challenges such as surgery, dental extractions, or trauma.

Diagnostic Approach

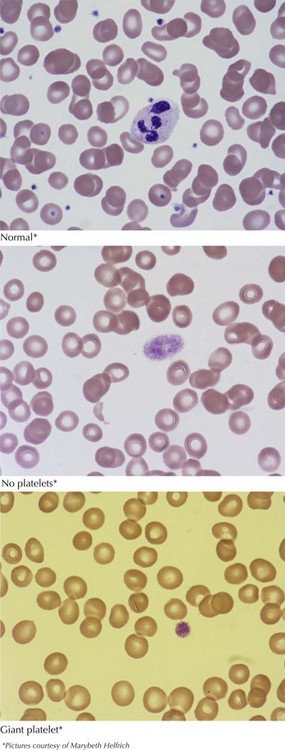

After the history and physical examination, a complete blood count should be obtained looking for thrombocytopenia. A blood smear should be examined, revealing differences in platelet size and the presence or absence of other hematologic abnormalities (Figure 52-3). If there is no thrombocytopenia present, formal platelet aggregation assays can help determine abnormalities in platelet function. A bleeding time is no longer recommended as a screening test for platelet disorders secondary to difficulty with standardization and unreliable results.

Aster RH, Bougie DW. Drug induced immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):580-587.

Cines DB, Bussel JB, Liebman HA, et al. The ITP syndrome: pathologic and clinical diversity. Blood. 2009;113(26):6511-6521.

Drachman JG. Inherited thrombocytopenia: when a low platelet count does not mean ITP. Blood. 2004;103(2):390-398.

Handin RI. Blood platelets and the vessel wall. In: Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, Look AT, editors. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:1457-1474.

Poncz M. Inherited platelet disorders. In: Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, Look AT, editors. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:1527-1546.

Warkentin T. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21(4):589-607.

Wilson DB. Acquired platelet defects. In: Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, Look AT, editors. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:1597-1630.