18 Plastic surgery

Spontaneous wound healing

Direct surgical wound closure

The first choice for wound repair is direct closure by suture, incision of which should be along the same axis line as the local skin creases (Langer lines – see Fig. 23.1, p. 339. Attention to detail is important with minimal handling of the skin edges, meticulous haemostasis and the wound sutured so that the edges are exactly matched but slightly everted. Hopefully hypertrophic scars can be avoided in this way (although true Keloid scarring is unpredictable and often difficult to manage, see Box 18.1)

Skin grafts

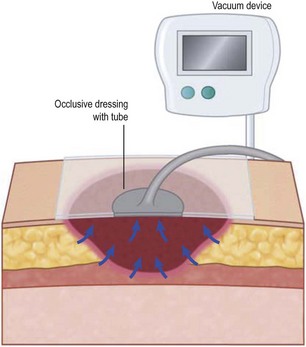

For a wound that cannot be closed directly the logical progression to achieve skin cover is skin grafting. Skin is harvested from elsewhere in the body and may be split or full thickness. The graft is ‘free’ and its continued survival depends on nutrients from the vascular bed of the wound: therefore drying-out, infection or the presence of necrosis will ensure failure. Split-skin grafts are usually harvested with powered dermatomes cutting the superficial layers of the skin 150–300 µm thick (the epithelial remnants ensure rapid healing of the donor site). Ingrowth of capillary loops is disrupted by any shearing forces so immobilisation of the ‘sheet’ of donor skin (and of the patient) is crucial, with sutures/staples/glues. ‘Meshing’ of the skin graft increases the area of cover achievable (Fig. 18.2), although cosmetically this leaves a cobbled appearance. Smaller wounds may get an improved cosmetic result with a full-thickness graft but consideration also has to be given to colour and texture if the wound is conspicuous (e.g. the face).

Flaps

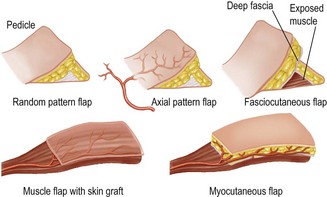

For reconstructing a deeper wound (or where skin alone is unlikely to ‘take’ or leave insufficient cover) the defect can be covered with a flap. This is a ‘block’ of tissue which retains an attachment to the body known as a pedicle, through which it receives its blood supply and innervation. Until a flap is incorporated within the defect, the pedicle must remain intact for the tissue to survive (a common cause of flap failure) (Fig. 18.3).

Flaps can be classified in three ways: