Chapter 5 Planning

Introduction

The healthcare system is a complex bureaucracy, driven not only by policy, budgets and changing technology, but also by the needs of many key stakeholders. Some authorities argue that the existing system of healthcare is not designed to effectively meet the needs and expectations of all stakeholders, particularly the needs of consumers, and that major reform is needed.1 The areas requiring particular attention relate to service access, efficiency, continuity of care, client participation in care and the coordination of health services.1,2 It is argued that all of these issues could be improved through the effective planning of care, of which more individualised, participative and coordinated treatment could be delivered over universalistic, problem-based, clinician-centred care. In fact, a goal-centred model of care is more likely to facilitate an interdisciplinary, client-centred approach, unlike problem-oriented or disease-oriented care, which place greater emphasis on physician control and measures of success.3 A client-centred approach is also more closely aligned with the core principles of CAM.

Despite the advantages of planning, it is claimed that few clinicians document clear goals in clinical practice, involve clients in the management of their care or fully understand individual concerns, beliefs and preferences. The reasons why practitioners might not engage in the planning of client care may relate to time limitations, system restraints, a lack of skill in developing client-centred goals or lack of awareness of the importance of goal setting.1,4,5 This is not surprising given that there is a lack of explicit instruction in and consensus on the process of care planning in the literature. To address these issues, this chapter proffers a clear, systematic framework for planning client care, taking into consideration the justification and concerns about the process, with a view to delivering a consistent and unequivocal approach to care planning in CAM practice, to enhance client care, improve clinical outcomes and ameliorate clinic, team and organisational efficiency.

Planning defined

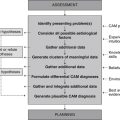

The planning phase of client care, which immediately follows clinical assessment and CAM diagnosis but precedes treatment and client review, is a projected course of action aimed at strategically addressing a client’s presenting problem. A key component of care planning is goal setting, which is fundamental in assisting the client and CAM practitioner in identifying and prioritising strategies that may prevent, reduce or resolve individual problems, or that facilitate or augment client function. These goals, or expected outcomes, also provide an endpoint towards which client care is directed by identifying a desirable psychological, social, physiological or cognitive state that is to be achieved.6 Planning is therefore an essential part of delivering healthcare and, as such, is an integral component of DeFCAM.

Rationale for planning

Care planning and goal setting generate several benefits for clients, CAM practitioners and institutions. Fundamentally, planning improves the organisation of client care by establishing common treatment objectives4 that pave a path towards a desired clinical outcome.7 These objectives provide an activity with a sense of purpose, relevance, clarity and control,8 which in turn improve continuity of care. As demonstrated in a number of studies, continuity of care can lead to improvements in client and clinician satisfaction, clinical outcomes and reduced episodes of care.1 Adequate planning is fundamental to improving continuity of care, as well as delivering a more consistent approach to care and, as such, would be conducive to interdisciplinary practice. The effective delivery of an integrative health service is a good case in point. If, for example, every individual practitioner in a healthcare team developed goals of care in isolation, then client care would almost certainly be fragmented and with probable overlap or omissions in care; it would be less efficient also. An integrative healthcare team that develops mutually derived goals, on the other hand, would be relatively more efficient and the care more consistent, as clinicians would be working towards common goals of care. This approach also could be associated with improvements in the coordination of client care, as well as enhanced communication between team members1,4 (see chapter 6 for a more detailed discussion of the benefits of interdisciplinary and integrative healthcare). Thus, by directing attention towards relevant activities and away from irrelevant actions,9 planning minimises the effect that external and internal factors have on achieving a goal by directing all efforts and resources towards a common goal.

As well as improvements in organisational efficiency, planning also ameliorates practitioner performance by motivating the clinician and integrative healthcare team to perform, by facilitating positive changes in practitioner behaviour, by increasing clinician accountability and autonomy and by rewarding the practitioner and client through the achievement of goals.1,4,5,10–12 CAM practitioners who set goals may also experience less emotional distress and demonstrate improvements in concentration, self-confidence and self-motivation.5 These improvements in clinician performance and morale, together with the increased level of client–practitioner interaction associated with goal setting, can significantly enhance the quality of client care.

Planning care and setting goals is particularly important in enabling the effective evaluation of clinical outcomes,4,13 as goals provide well-defined, measurable endpoints of care. The purposeful appraisal of client goals may promptly identify delays in the achievement of expected outcomes and thus effectively determine if a treatment needs to be modified or altered to better meet client needs.14 Other than providing assurance that client needs have been effectively met, care planning, when used in conjunction with client review, can also provide a means for evaluating the performance of clinicians,6,15 the efficacy of selected interventions, the effect of the therapy on client outcomes and, thus, the efficiency of a clinic or institution. In other words, care planning could be used as an effective auditing or quality management tool.15

One clinical outcome that is positively correlated with goal attainment is quality of life. In a case series study using a within-subjects, repeated measures design, in which 47 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome were required to set three to five individualised goals for a 4-month support and education program, goal attainment was found to be the only predictor of quality of life. This was independent of sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, and fatigue and symptom severity.16 Although other confounding factors, such as available support structures, may have contributed to these findings, the positive association between goal attainment and health-related quality of life continues to be supported across several diverse client populations, including individuals post-myocardial infarction17 and those following pelvic floor dysfunction surgery.18

In a community psychiatric nursing service in Sussex, the nursing process was incorporated into departmental documentation with a view to delivering a more organised service. After the integration of the nursing process, it was noted that the turnover rate of patients increased. The reason for this was that the nursing process, in particular the clearly documented treatment objectives, enabled nurses to clearly identify when a client’s problem had resolved and when nursing care was no longer required. The service also observed after the integration of the process an improvement in staff morale and performance, the quality of nursing care and the professionalism of staff.19 Although the findings of this system evaluation are anecdotal, the integration of the nursing process into perioperative assessment forms within a Cincinnati paediatric burns unit resulted in similar changes, including subjective improvements in staff satisfaction, service efficiency and client care delivery.6

Similar improvements in healthcare service delivery have also been observed in spinal rehabilitation, an area that is particularly relevant to practitioners of manipulative therapies. An evaluation of existing practice in a Canadian spinal cord rehabilitation centre, for instance, identified several discrepancies in clinical documentation, a lack of client participation in the planning of care, a lack of interdisciplinary action and the adoption of a discipline-driven, problem-based approach to client care following a series of semistructured interviews.20 These concerns prompted the integration of a Donabedian structure–process–outcome goal-setting framework into all relevant client and interdisciplinary documentation. Despite initial resistance and scepticism towards the changing approach to client care, the difficulty in establishing target dates for each goal and the effort to actively involve clients in the setting and prioritisation of goals, the 12-month evaluation of the new framework (by way of team meeting audits) revealed some positive outcomes for clinicians and clients. By demonstrating a shift towards a more goal-oriented, team-driven approach to client care, staff reported an improvement in the structure and organisation of meetings, increased accountability for the documented actions aligned to each goal and greater clarity over team expectations.20 Clients, through increased participation in the rehabilitation process, demonstrated increased accountability towards achieving goals.

Several clinical studies add further support to the positive correlation between the adoption of goal planning and improved client outcomes, including clients with knee injury,21 cerebral palsy,22 sports injury,23,24 rheumatoid arthritis,25 brain injury,26 spinal cord injury27 and individuals requiring dietary changes.28,29 While these improvements occurred in orthodox clinical environments, it is envisaged that similar changes to client outcomes would occur in CAM practice, although further research in this area is needed to verify this claim.

Concerns about planning

To this point, the careful planning of client care appears to be a simple and effective strategy that can improve healthcare outcomes. Yet not all authorities share this point of view. Some argue that planning is an innate, unconscious activity that many practitioners already perform8 and that a prescribed planning framework is not necessary for delivering superior client care. However, it is uncertain whether this innate process of planning is administered in a systematic, rationalised and client-centred manner. Given the evidence presented above, it is unlikely that this is the case. To ensure that care is planned in a manner that is purposeful, justified and systematically administered, several key concerns need to be addressed.

The planning of care and the formulation of goals in a participatory manner require a rise in clinician workload and an increase in the time allocated to documentation.4,27 In view of the increasing demand for CAM services,30 the probable constraints on practitioner time and the need to deliver a financially viable service, it may be difficult for some CAM practitioners to effectively plan client care. Some clinicians may also view the planning of care as restrictive and intrusive to the therapeutic relationship,31 though this is only likely if a paternalistic approach to goal setting, in which client collaboration and respect are not usually considered, is adopted.

A qualitative exploratory study of practising nurses across five contrasting hospital wards in Northern Ireland corroborated concerns, through the use of participant observation, focus groups and diaries, that the process of creating and maintaining care plans may be an unnecessary burden on the provision of care. One ward did view care plans favourably. Apart from the fact that care plans were more effectively integrated into practice in the exceptional ward, this positive perception of care plans may have been attributed to the different approach to care planning, where care plans were not only more individualised, but were also created by staff in collaboration with the client.32 This participatory approach to care planning, as highlighted below, is not only pivotal in facilitating client rapport and alleviating anxiety, but in the long-term may also contribute to fewer follow-up consultations, greater patient cost savings and a more competitive health service by expediting the achievement of desired clinical outcomes. Given the time and resources that can be saved though goal setting,31 and the many immediate and long-term benefits associated with the planning of care, it would be undesirable if goal setting were depreciated by CAM practitioners or, at worst, completely disregarded.

Planning client care in order to effectively develop mutually derived goals also requires effective communication between the client and CAM practitioner.4 Although greater interaction between a client and clinician demands additional time, which may already be constrained, not taking the time to listen to the client and, in effect, not providing an environment that fosters rapport, may compromise the quality of a client’s assessment and the accuracy of the diagnosis and, subsequently, adversely affect the outcome of the prescribed treatment.

Some authorities also argue that planning is limited by the capabilities of the individual and as a result cannot be applied to all clients. Atkinson,31 for example, points out that individuals with acute psychotic illness, serious ill health, aphasia, cognitive or sensory impairments and clients from non-English-speaking backgrounds may not be suitable for setting mutually derived goals because client motivation and understanding are fundamental requirements for goal attainment.33 Nevertheless, these limitations can be easily resolved through the provision of alternative and innovative communication aids and the involvement of family and significant others,31 which provides some assurance that care is planned around client needs, capacity and preference.

The planning process

As previously highlighted, DeFCAM provides a systematic approach to the planning and implementation of client care; however, before treatment goals can be developed and a care plan established, client problems need to be prioritised. The choice about which diagnosis to address foremost should be determined by the level of risk that the problem poses to the client, with conditions demonstrating a higher risk of harm demanding a higher priority of care.34,35 Of course, in keeping with client-centred care, the prioritisation of problems should also take into account client preference and readiness to change. Once diagnoses have been prioritised, the most important diagnosis then can be used to formulate the goals of treatment.

According to Wright,13 treatment goals must be SMART – specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-specific – but to achieve this, each goal must address only one problem and one outcome.5,34,35 Even though SMART is a useful aid for setting goals, it ignores other essential criteria for goal setting, including the need for goals to be client-centred, adequately documented and mutually derived. A summary of the necessary criteria for setting goals and expected outcomes is illustrated in Figure 5.1. It is also necessary to examine some of these criteria in further detail to highlight the importance of these factors in the planning process.

To begin with, goal setting should be participative or mutually derived in that the client should be actively involved, as this is more likely to motivate the client to set higher goals and to achieve these targets.5,33 This may be because the client is more likely to take some ownership of and responsibility towards achieving these goals.4 This is particularly pertinent to CAM practice, as many CAM therapies demand a relatively greater degree of behavioural change from clients (i.e. dietary modification, lifestyle change, mind–body therapy) than that expected from orthodox medicine, where compliance is primarily limited to medication administration. Given that client actions are central to treatment success, it is also important that goals are client-centred, individualised and written from the client’s perspective, not from the clinician’s standpoint, so that goals are meaningful and relevant to the client.15 A comparison between client-centred goals and practitioner-centred goals is illustrated in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Comparing client-centred goals with practitioner-centred goals

| CAM diagnosis | Client-centred goal | Practitioner-centred goal |

|---|---|---|

| ADL dependence (actual), secondary to rheumatoid arthritis… | The client will demonstrate greater independence with ADLs. | Joint pain will be adequately controlled. |

| Dysuria (actual), secondary to symptomatic bacteriuria… | The client will be free from dysuria. | Bacteriuria will be absent. |

| Flat affect (actual), secondary to hypothyroidism… | The client will report an improvement in affect. | Serum thyroxine levels will remain within normal range. |

| Poor exercise tolerance (actual), secondary to asthma… | The client will report an improvement in exercise tolerance. | Peak expiratory flow rate will be maintained within the age-adjusted range. |

| Lethargy (actual) secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus… | The client will be less lethargic. | Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) will be under 7.0%. |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living

A participative approach to care planning provides some assurance that goals are achievable and realistic for the client, although studies comparing practitioner-assigned goals with participative-set goals in the 1970s and 1980s have yielded inconsistent results in relation to client performance.9,36 Factors contributing to these disparate findings may relate to variations in study duration, settings, interventions, degree of participant input and level of subject support and follow-up. More recent findings are beginning to shift the scales of evidence in favour of a client-centred approach.

In one poorly defined study of 27 patients with urinary incontinence, patients who were actively involved in the setting of their treatment goals were more likely to report successful outcomes.37 Another qualitative study, which interviewed 18 neurological rehabilitation patients, discovered that collaborative goal setting may also increase client motivation, perceptions of control and freedom in decision making.37,38 While some may argue that these qualitative studies are unable to establish a cause and effect relationship between goal setting and clinical outcomes, findings from well-designed controlled studies can.

Adding support to these studies are findings from a randomised controlled trial of 77 rehabilitation patients that found participative goal setting, when compared to physiotherapist-directed care, resulted in higher ratings on quality of care scales and better clinical outcomes for range of motion, strength and balance at discharge.39 Evidence indicates, then, that a more paternalistic approach to care planning may attenuate the progression towards goal-attainment, reduce individual autonomy and promote a sense of helplessness among clients.10

Despite the rationale for adopting a participative approach to goal setting, studies indicate that some clinicians may still be using a paternalistic approach. In a postal survey of 202 representative members of the British society of rehabilitation medicine, for example, only forty-two per cent of respondents indicated that they used a participative approach to goal setting, less than forty per cent fully involved patients in the setting of goals and less than thirty per cent involved patients in the evaluation of set goals.40 The authors claimed that this paternalistic approach may have stemmed from a lack of resources and to insufficient practitioner skill and knowledge of effective goal setting. Some clinicians may have also believed that they were acting in the person’s best interests when setting goals without client input, but several studies across different populations indicate that there is significant disagreement between treatment goals set by practitioners and those set by clients and family members.41,42 It is likely that many clinicians will benefit from being informed about the process and outcomes of effective care planning and the need to involve clients in goal setting. A list of potential questions that could facilitate the identification of client-centred goals and further CAM practitioner progress through the planning process is listed in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Questions to assist clients and CAM practitioners in identifying appropriate treatment goals

| Overall concerns

Presenting condition |

Apart from being client-centred, goals should also be clear and specific, as this is likely to eliminate confusion and potential misinterpretation among clients and CAM practitioners. It is also important that goals are measurable, as this is necessary in determining whether the client has achieved or is working towards their goal and to what extent the client has progressed towards this defined endpoint. In addition to being clear, specific and measurable, goals should also be time-limited or date-stamped. These dates (dd/mm/yyyy), which generally reflect the date of the next appointment, provide motivation for the client and clinician to work towards the goal,13 reduce ambiguity about the achievement of an expected outcome5,9 and identify when further intervention is needed.

Treatment goals must also take into consideration the cost of treatment, available resources, staffing, client age, environment, values, beliefs, culture and social status, and the cognitive, physical and emotional capacity of the client.31,43 If, for example, an individual does not have the functional capacity to perform key tasks, is not motivated or ready to try a new treatment, cannot afford to purchase the treatment or does not accept or understand the existence or consequences of their illness, they are less likely to achieve their treatment goal. Put simply, goals should be achievable in that available resources, practitioner skill and client ability and desire should enable the target to be achieved.

Effective assimilation of these criteria into the planning of client care can be facilitated using the following two-stage process. The first step of this process involves the construction of general goals that are the overall desired outcomes of care,7 taking into account the factors that can influence treatment success, yet not explicitly stating how the goals will be achieved. These general goals can be centred around the following themes: safety, independence, social and family relationships, personal health (including physical, emotional, mental and spiritual), economic stability and autonomy.7 An example of a general goal for a client with impaired mobility secondary to osteoarthritis may be that ‘The client will walk independently without mobility aids’.

The second step of the planning process is the expected outcomes, or explicit goals. These outcomes direct clinical care by specifically indicating how and when the general goals of treatment might be achieved. As illustrated in several studies to date,44,45 it is important that long-term and short-term outcomes are included, as long-term objectives alone are less likely to lead to improved clinical outcomes. An episode of care is therefore likely to encompass multiple goals and expected outcomes, with many of these endpoints emerging and resolving at different points in time.

As do goals, expected outcomes should also be client-centred so that endpoints remain pertinent to individual needs. To achieve client-centredness, expected outcomes need to be directly related to the presenting complaint and planned goals. These endpoints also need to focus on addressing the goals of care. To ensure that outcomes can be effectively evaluated, endpoints also need to be measurable, time-limited and include a client behaviour and criterion of acceptable behaviour.46 An example of an expected outcome for an individual with dehydration is as follows: ‘The client (client-centred) will drink (behaviour) 1500 mL of water a day (realistic, measurable criterion) by dd/mm/yyyy (time-limited)’. Further examples of the two-stage planning process, in particular how goals and expected outcomes interface with CAM diagnoses, are presented in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3 Examples of the two-stage planning process, including a general goal and expected outcomes (EO)

| Acne | |

| CAM diagnosis | Acne (actual), related to altered immune-function, high glycaemic load diet and nutritional imbalance |

| Goal | Client will be free from acneiform lesions |

| EO | |

| Arthralgia | |

| CAM diagnosis | Arthralgia (actual), secondary to osteoarthritis, related to elevated proteolytic enzyme activity, impaired cartilage formation and increased proinflammatory cytokine levels |

| Goal | Client will experience an improvement in joint pain |

| EO | |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) | |

| CAM diagnosis | Cerebrovascular accident (potential), related to hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension |

| Goal | Client will not experience a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) |

| EO | |

| Constipation | |

| CAM diagnosis | Constipation (actual), related to inadequate fluid intake, sedentary lifestyle and insufficient fibre intake |

| Goal | Client will demonstrate an improvement in bowel activity |

| EO | |

| Cough | |

| CAM diagnosis | Productive cough (actual), secondary to lower respiratory tract infection, related to altered immune function |

| Goal | Client will be free from a productive cough |

| EO | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| CAM diagnosis | Hyperglycaemia (potential), secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus, related to high glycaemic load diet, sedentary lifestyle and insulin resistance |

| Goal | Client will experience few episodes of hyperglycaemia |

| EO | |

| Diarrhoea | |

| CAM diagnosis | Chronic diarrhoea (actual), secondary to irritable bowel syndrome, related to intestinal dysbiosis |

| Goal | Client will demonstrate reduced episodes of diarrhoea |

| EO | |

| Dysmenorrhoea | |

| CAM diagnosis | Dysmenorrhoea (actual), related to elevated oestrogen levels, elevated prostaglandin levels and progesterone deficiency |

| Goal | Client will demonstrate an improvement in menstrual pain |

| EO | |

| Dysuria | |

| CAM diagnosis | Dysuria (actual), secondary to urinary tract infection, related to inadequate fluid intake and immune dysfunction |

| Goal | Client will be free from dysuria |

| EO | |

| Headache | |

| CAM diagnosis | Headache (actual), related to poor posture and spinal misalignment |

| Goal | Client will be free from recurrent headaches |

| EO | |

| HIV infection | |

| CAM diagnosis | HIV infection (actual), related to unprotected sex with HIV-infected partner |

| Goal | Client will not develop AIDS |

| EO | |

| Hypertension | |

| CAM diagnosis | Hypertension (actual), related to excessive sodium intake and excessive saturated fat consumption |

| Goal | Client will demonstrate a reduction in blood pressure |

| EO | |

| Obesity | |

| CAM diagnosis | Obesity (actual), related to increased energy intake, decreased energy expenditure and insulin resistance |

| Goal | Client will demonstrate a reduction in body weight |

| EO | |

| Retinopathy | |

| CAM diagnosis | Diabetic retinopathy (potential), secondary to diabetes mellitus, related to poor glycaemic control |

| Goal | Client will not demonstrate any signs of diabetic retinopathy |

| EO | |

| Sinus congestion | |

| CAM diagnosis | Sinus congestion and pain (actual), secondary to chronic sinusitis, related to food intolerance and poor mucous membrane integrity |

| Goal | Client will be free from sinus congestion and pain |

| EO | |

Summary

The careful planning of client care generates immediate and long-term benefits for clients, CAM practitioners, the integrative healthcare team, administrators and the healthcare system, including improvements in communication, clinician performance, clinic and organisational efficiency, client quality of life and clinical outcomes. However, care planning is not an innate, unconscious activity but one that is systematic and rationalised and requires an appropriate level of skill to plan at a competent level. This chapter has highlighted that the use of a clear, systematic planning framework that integrates goals and expected outcomes that are client-centred, mutually derived, specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited may help to deliver a transparent and consistent approach to client care and in doing so greatly improve client health and wellbeing by hastening the achievement of clinical outcomes. In the chapter that follows, the application of client care is discussed, particularly the role of evidence-based practice as a component of clinical care.

Learning activities

1. Bergeson S., Dean J. A systems approach to patient-centered care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(23):2848-2851.

2. Leach M.J. Integrative healthcare: a need for change? Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine. 2006;3(1):1-11.

3. Mold J., Blake G., Becker L. Goal-oriented medical care. Family Medicine. 1991;23:46-51.

4. Holliday R. Goal-setting: just how client-oriented are we? Therapy Weekly. 2004;30(37):8-11.

5. Kraus J. The importance of goal setting. Podiatry Management. 2006;25(4):121-125.

6. Mesmer R. Patient-focused perioperative documentation: an outcome management approach. Seminars in Perioperative Nursing. 1997;6(4):223-232.

7. Bradley E., et al. Goal-setting in clinical medicine. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;49:267-278.

8. Hinderer S. Practically perfect planning. Seminars in Perioperative Nursing. 1996;5(3):157-164.

9. Locke E., Latham G. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist. 2002;57(9):705-717.

10. McGillan P. Assessment and care planning increase autonomy of practice. Provider. 1990;16(6):37-38.

11. Playford E.D., et al. Goal-setting in rehabilitation: report of a workshop to explore professionals’ perceptions of goal-setting. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2000;14:491-496.

12. Wade D.T. Evidence relating to goal planning in rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation. 1998;12:273-275.

13. Wright K. Care planning: an easy guide for nurses. Nursing and Residential Care. 2005;7(2):71-73.

14. Leach M.J. Revisiting the evaluation of clinical practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2007;13(2):70-74.

15. Wallen M., Doyle S. Performance indicators in paediatrics: the role of standardized assessments and goal setting. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1996;43:172-177.

16. Query M., Taylor R. Linkages between goal attainment and quality of life for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2005;19(4):3-22.

17. Boersma S., et al. Goal processes in relation to goal attainment: predicting health-related quality of life in myocardial infarction patients. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(6):927-941.

18. Hullfish K., Bovbjerg V., Steers W. Patient-centered goals for pelvic floor dysfunction surgery: long-term follow-up. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(1):201-205.

19. Manchester J. A framework for planning. Nursing Mirror. 1983;156(15):34-36.

20. Heenan C., Piotrowski U. Creation of a client goal-setting framework. SCI Nursing. 2000;17(4):153-161.

21. Theodorakis Y., et al. The effect of personal goals, self-efficacy, and self-satisfaction on injury rehabilitation. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation. 1996;5:214-223.

22. Bower E., et al. A randomised controlled trial of different intensities of physiotherapy and different goal-setting procedures in 44 children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1996;38(3):226-237.

23. Evans L., Hardy L. Injury rehabilitation: a goal-setting intervention study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2002;73(3):310-319.

24. Theodorakis Y., et al. Examining psychological factors during injury rehabilitation. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation. 1997;6:355-363.

25. Stenstrom C. Home exercise in rheumatoid arthritis functional class II: goal setting versus pain attention. Journal of Rheumatology. 1994;21(4):627-634.

26. Gauggel S., Leinberger R., Richardt M. Goal setting and reaction time performance in brain-damaged patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001;23(3):351-361.

27. Macleod G.M., Macleod L. Evaluation of client and staff satisfaction with a goal planning project implemented with people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 1996;34(9):525-530.

28. Berry M., et al. Work-site health promotion: the effects of a goal-setting program on nutrition-related behaviors. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1989;89(7):914-920. 923

29. Cullen K., et al. Goal setting is differentially related to change in fruit, juice, and vegetable consumption among fourth-grade children. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(2):258-269.

30. MacLennan A.H., Myers S.P., Taylor A.W. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(1):27-31.

31. Atkinson J. Goal setting in rehabilitation: costs, benefits and challenges. Therapy Weekly. 2004;30(46):10-13.

32. Mason C. Guide to practice or ‘load of rubbish’? The influence of care plans on nursing practice in five clinical areas in Northern Ireland. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(2):380-387.

33. Barclay L. Exploring the factors that influence the goal setting process for occupational therapy intervention with an individual with spinal cord injury. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2002;49:3-13.

34. Crisp J., Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s fundamentals of nursing, 3rd ed. Sydney: Elsevier Australia; 2008.

35. Harkreader H. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical judgement, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007.

36. Alexy B. Goal setting and health risk reduction. Nursing Research. 1985;34:283-288.

37. Roe B., et al. An evaluation of health service interventions by primary healthcare teams and continence advisory services on patient outcomes related to incontinence. Oxford: Health Services Research Unit, Oxford University; 1996.

38. Conneeley A. Interdisciplinary collaborative goal planning in a post-acute neurological setting: a qualitative study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;67(6):248-255.

39. Arnetz J., et al. Active patient involvement in the establishment of physical therapy goals: effects on treatment outcome and quality of care. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2004;6(2):50-69.

40. Holliday R., Antoun M., Playford E. A survey of goal-setting methods used in rehabilitation. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2005;19(3):227-232.

41. Glazier S., et al. Taking the next steps in goal ascertainment: a prospective study of patient, team, and family perspectives using a comprehensive standardised menu in a geriatric assessment and treatment unit. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:284-289.

42. Marteau T., et al. Goals of treatment in diabetes: a comparison of doctors and parents of children with diabetes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1987;10(1):33-48.

43. Berman A., et al. Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing: concepts, process, and practice, 8th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2008.

44. Bandura A., Simon K.M. The role of proximal intentions in self-regulation of refractory behaviour. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1977;1(3):177-193.

45. Bar-Eli M., Hartman I., Levy-Kolker N. Using goal setting to improve physical performance of adolescents with behaviour disorders: the effect of goal proximity. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 1994;11:86-97.

46. Murray M.E., Atkinson L.D. Understanding the nursing process in a changing care environment, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.