Physiology of the skin

The skin is a metabolically active organ with vital functions (Table 1), including the protection and homeostasis of the body.

Keratinocyte maturation

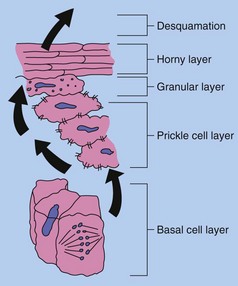

Epidermal cells undergo the following sequence during keratinocyte maturation (Fig. 1):

1. Undifferentiated cells in the basal layer and the layer immediately above divide continuously. Half of these cells remain in place, and half progress upwards and differentiate.

2. In the prickle cell layer, cells change from being columnar to polygonal. Differentiating keratinocytes synthesize keratins, which aggregate to form tonofilaments. The desmosomes connecting keratinocytes are composed of the structural molecules cadherins, desmogleins and desmocollins. Desmosomes distribute structural stresses throughout the epidermis and maintain a distance of 20 nm between adjacent cells.

3. In the granular layer, enzymes induce degradation of nuclei and organelles. Keratohyalin granules containing filaggrin mature the keratin and provide an amorphous protein matrix for the tonofilaments. Membrane-coating granules attach to the cell membrane and release an impervious lipid-containing cement, which contributes to cell adhesion and to the horny layer barrier.

4. In the horny layer, the dead, flattened corneocytes have developed thickened cornified envelopes containing involucrin that encase a matrix of keratin macrofibres aligned by filaggrin. The strong disulphide bonds of the keratin provide strength to the stratum corneum, but the layer is also flexible and can absorb up to three times its own weight in water. However, if it dries out (i.e. water content falls below 10%), pliability fails.

5. The corneocytes are eventually shed from the skin surface after degradation of the lamellated lipid and loss of desmosomal intercellular connections.

Hair growth

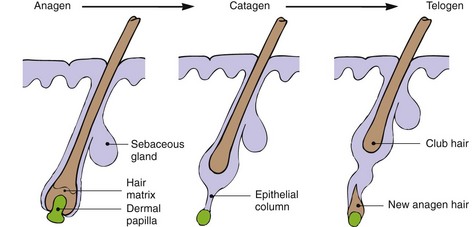

The rate of hair growth differs depending on the site. For example, eyebrow hair grows faster and has a shorter anagen (see below) than scalp hair. On average, there are about 100 000 hairs on the scalp, and the normal rate of growth is 0.4 mm/24 h. Hair growth is cyclical, with three phases, and is randomized for individual hairs, although synchronization does occur during pregnancy. The three phases of hair development (Fig. 2) are anagen, catagen and telogen.

1. Anagen is the growing phase. For scalp hair, this lasts from 3 to 7 years but, for eyebrow hair, it lasts only 4 months. At any one time, 80–90% of scalp hairs are in anagen, and about 50–100 scalp follicles switch to catagen per day.

2. Catagen is the resting phase and lasts 3–4 weeks. Hair protein synthesis stops, and the follicle retreats towards the surface. At any one time, 10–20% of scalp hairs are in catagen.

3. Telogen is the shedding phase, distinguished by the presence of hairs with a short club root. Each day, 50–100 scalp hairs are shed, with less than 1% of hairs being in telogen at any one time.

Melanocyte function

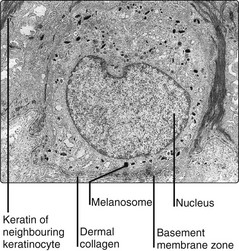

Melanocytes (located in the basal layer) produce the pigment melanin in elongated, membrane-bound organelles known as melanosomes (Fig. 3). These are packaged into granules, which are moved down dendritic processes and transferred by phagocytosis to adjacent keratinocytes. Melanin granules form a protective cap over the outer part of keratinocyte nuclei in the inner layers of the epidermis. In the stratum corneum, they are uniformly distributed to form a UV-absorbing blanket, which reduces the amount of radiation penetrating the skin. Thickening of the epidermis also blocks UV.

Variations in racial pigmentation result not from differences in melanocyte numbers, but in the number and size of melanosomes produced. Gene polymorphisms in red-haired people cause impaired melanocyte-stimulating hormone signalling to the MC1-receptor, which leads to reduced levels of melanocyte eumelanin (brown/black) and therefore predominantly red phaeomelanin (p. 8).

Thermoregulation

Blood flow

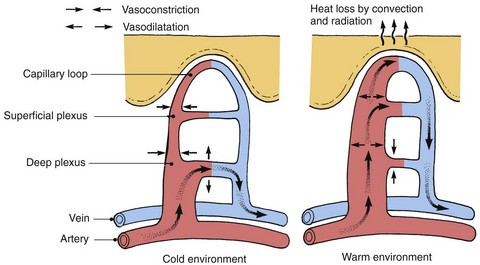

Skin temperature is highly responsive to skin blood flow. Dilatation or contraction of the dermal blood vessels results in vast changes in blood flow, which can vary from 1 to 100 mL/min per 100 g of skin for the fingers and forearms. Arteriovenous anastomoses under the control of the sympathetic nervous system shunt blood to the superficial venous plexuses (Fig. 4), affecting skin temperature. Local factors, both chemical and physical, can also have an effect.

Sweat

a low concentration of Na+ (30–70 mEq/L) and Cl− (30–70 mEq/L)

a low concentration of Na+ (30–70 mEq/L) and Cl− (30–70 mEq/L)

a high concentration of K+ (up to 5 mEq/L), lactate (4–40 mEq/L), urea, ammonia and some amino acids.

a high concentration of K+ (up to 5 mEq/L), lactate (4–40 mEq/L), urea, ammonia and some amino acids.

Only small quantities of toxic substances are lost.

Physiology