12 Physiology of pregnancy and pregnancy problems

Physiology of pregnancy

Gastrointestinal

Pregnancy is associated with delayed gastric emptying and delayed lower gastrointestinal transit.

Minor disorders of pregnancy

Nausea and vomiting

Antiemetics

Corticosteroids have been shown to improve symptoms of hyperemesis in intractable cases.

Ginger and acupressure are alternative evidence-based treatments.

Skin problems

Itching

Many pregnant women experience itching, commonly over the abdomen. It is generally not associated with a rash, except for that due to excoriation, and liver function tests are normal. Suspicious features warranting further investigation are itching on the palms and soles, abnormal liver function or a rash (see obstetric cholestasis, below).

Symphysis pubis dysfunction

Treatment is supportive with crutches, pelvic support braces and analgesia.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Prediction

Risk factors for the development of pre-eclampsia are shown in Table 12.1.

| Primiparity |

| Multiple pregnancy |

| Obesity |

| Extremes of age |

| New partner |

| In vitro fertilization – egg donation |

| Diabetes |

| Chronic hypertension |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome |

| Renal disease |

| Molar pregnancy |

Investigations

Treatment of hypertension

Intrapartum management

The mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) should be maintained below 125. MAP is calculated as follows:

Timing of delivery

Severe hypertension or pre-eclampsia in labour

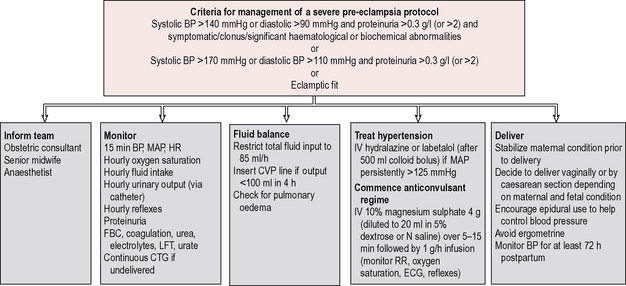

A protocol should be adhered to for all women with significant disease. Important considerations in the management are summarized in Figure 12.1 and include:

2. Fluid restriction: fluid input should be restricted to 85 ml/hour, due to the intravascular depletion associated with pre-eclampsia.

3. Treatment of blood pressure: the treatment of blood pressure is outlined above.

4. Delivery: induction of labour or caesarean section (depending on obstetric factors) should be initiated when the maternal haemodynamic condition is stable. Epidural is encouraged as it reduces blood pressure, though platelets should be checked first as there is a risk of epidural haematoma if the platelet count is less than 80 × 109/l. Syntocinon alone is used for the third stage as ergometrine may precipitate a further rise in blood pressure.

5. Magnesium sulphate: magnesium sulphate decreases the likelihood of an eclamptic fit and should be considered in severe pre-eclampsia. A loading dose of 2 grams (diluted in 20 ml normal saline) over 5 minutes is followed by an infusion of 1–2 g/hour. Side effects are hot flushing sensation, loss of tendon reflexes, respiratory depression and cardiac arrest. The urine output, reflexes, blood pressure, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation should be monitored closely, with cardiac monitoring. Magnesium sulphate also lowers blood pressure and care is needed with other hypertensives to prevent a sudden drop in blood pressure, which may cause fetal distress. Magnesium sulphate should be continued for 24 hours postpartum.

Complications of pre-eclampsia

Pulmonary oedema

Pulmonary oedema occurs as a result of the hypoalbuminaemia and vascular endothelial dysfunction.

Antepartum haemorrhage

Aetiology

Bleeding may occur from a maternal, fetal or placental site (Table 12.2). Both placental and maternal sites involve loss of maternal blood, whereas in the case of vasa praevia fetal blood is lost.

| Maternal | Placental | Fetal |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal infectionstart=”row” colname=”col1″ align=”left”(e.g. Candida, Trichomonas) | Placenta praevia | Vasa praevia |

| Cervical ectropion | Placental abruption | |

| Cervical infection | ||

| Cervical malignancy | ||

| Bloody show | ||

| Uterine rupture |

History

Important features in the history of a woman presenting with suspected APH are:

• The colour, consistency and amount of blood loss. Placenta praevia blood loss tends to be fresh and red whereas blood associated with abruption may be darker. It is useful to attempt to quantify loss by comparing it to the patient’s usual menstrual loss or number of pads used.

• The duration of bleeding and any possible triggering factors, such as sexual intercourse.

• Any previous bleeding episodes.

• Abdominal pain – a feeling of uterine ‘tightening’ or pelvic discomfort are all important features suggesting a possible placental abruption. Bleeding associated with a placenta praevia tends to be painless (80%), unless labour has started.

• Labour – a small amount of blood loss is common with a ‘show’ and more significant bleeding may occur during precipitate labour. A mucus-like blood loss, rupture of membranes or contractions may, therefore, suggest APH due to labour.

• Fetal movements – bleeding with loss of fetal movements is suspicious of abruption.

• The date and result of the most recent cervical smear and details of any previous sexually transmitted or other genital infections, such as candida.

• Placental site, as described in the most recent ultrasound report.

Investigations

Women reporting APH should all have the following investigations:

• Crossmatch – depending on the estimated blood loss

• Coagulation studies – if a coagulopathy is suspected or blood loss is massive. Low fibrinogen, increased D-dimer, prolonged prothrombin time and APTT, and low platelets suggest DIC, usually following abruption

• Kleihauer test – particularly important for Rhesus-negative women to determine the dose of anti-D required. The result of a Kleihauer test is not immediate enough, however, to help in initial management.

• CTG – commenced as early as possible to ascertain fetal well-being and monitor uterine activity.

• Ultrasound – requested urgently if the placental site is unclear, to look for placenta praevia. Retroplacental blood clot may be visualized on scan after an abruption, but it is often not, and if a large clot is present then the likelihood is that fetal demise has already occurred and the woman is extremely unwell. Abruption is, therefore, essentially a clinical diagnosis, though ultrasound may help to exclude placenta praevia as an alternative cause of the bleeding.

• High vaginal swab – to exclude Candida and full vaginal and cervical swabs should be sent if an infective cause of bleeding is suspected.

Management

Both placenta praevia and placental abruption are associated with a high risk of postpartum haemorrhage, and active management of the puerperium with Syntocinon and ergometrine at delivery followed by a Syntocinon infusion is necessary. The management of postpartum haemorrhage is covered in Chapter 17.

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia is implantation of the placenta in the lower segment of the uterus, occurring in 1% of pregnancies at term. It is classified according to how close the leading edge of the placenta is to the internal cervical os, as shown in Figure 17.1. Bleeding may occur due to the thinning of the cervix and lower segment of the uterus in late pregnancy or in early labour. If bleeding occurs in a woman with placenta praevia, then admission until delivery is normally necessary. The mother should have regular haemoglobin measurement and anaemia treated with iron or blood transfusion, if necessary. Four units of crossmatched blood should be readily available in case of sudden haemorrhage.

Placental abruption (abruptio placentae)

Management of a suspected abruption includes admission to the labour ward, insertion of two large-bore intravenous cannulae, crossmatching of 4 units of blood and correction of any coagulopathy. If the estimated blood loss is significant, the urinary output should be monitored via a urinary catheter and a central venous line may be inserted to manage fluid balance more accurately. The management of obstetric haemorrhage is covered further in Chapter 17. Continuous CTG is commenced if the fetus is still alive.

If pre-eclampsia is present, this must be treated simultaneously.

Complications of placental abruption

Table 12.3 summarizes the differences between the typical presentations of placenta praevia and placental abruption, but it should be remembered that many presentations are atypical and that the two conditions may coexist.

Table 12.3 Summary of the differences between placenta praevia and placental abruption

| Placenta praevia | Placental abruption |

|---|---|

| Painless (80%) | Constant pain or high-frequency contractions |

| Clinical condition correlates | Clinical condition suggests more |

| with visible blood loss | blood loss than visualized |

| Soft, non-tender uterus | Tender, tense uterus |

| High presenting part or | May be unable to palpate fetal parts |

| malpresentation | due to tense uterus |

| Ultrasound diagnosis | Clinical diagnosis |

| Low risk to the fetus | Fetus at high risk |

| Caesarean section essential | Caesarean only if bleeding |

| uncontrolled or fetal compromise |

Vasa praevia

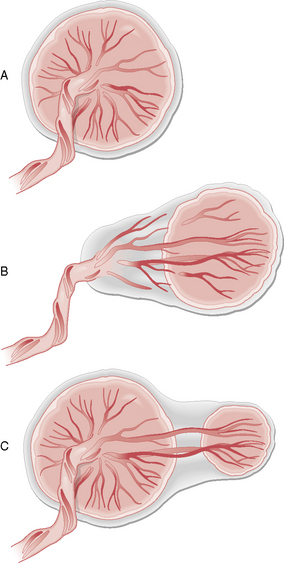

‘Vasa praevia’ is the term used where umbilical cord vessels abnormally traverse the membranes and overlie the internal cervical os. It occurs in 1 in 3000 pregnancies and is associated with either a velamentous insertion of the cord into the placenta (from the side) or with a succenturiate (satellite or accessory) lobe of placenta (Fig. 12.2). The vessels are at risk of tearing when they are stretched during cervical dilatation in labour or during ARM.

There is no significant risk to the mother from vasa praevia.

Cervical lesions

Various cervical lesions may account for APH. The commonest is a cervical ectropion, which may be diagnosed on speculum and managed conservatively. Cauterization is avoided in pregnancy and the ectropion often resolves in the puerperium. Infections such as Trichomonas may cause cervicitis and bleeding and should be treated accordingly (see Chapter 9).

Infections of pregnancy

Rubella

Toxoplasmosis

Maternal infection

Treatment of the mother with spiramycin may reduce the chance of fetal infection.

Cytomegalovirus

The virus is transmitted through urine, saliva and other body products.

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is discussed in Chapter 9. The incidence of HIV infection is up to 1 in 200 pregnant women in some areas of the UK. Transmission occurs by sexual contact (heterosexual or homosexual), infected blood products (e.g. needle sharing) or vertical transmission.

Neonatal HIV infection is more likely in the presence of:

• Prolonged rupture of membranes (> 4 hours)

• Invasive procedures (fetal blood sampling, instrumental delivery, episiotomy, fetal scalp electrode).

Management around delivery

1. Caesarean section delivery, ideally maintaining intact membranes until the head has been delivered and avoiding contact between the baby and the maternal blood

2. Delivery within 4 hours if spontaneous rupture of membranes occurs, ideally by caesarean section

3. Zidovudine prophylaxis intravenously to the mother for 4 hours prior to delivery and to the baby orally for 6 weeks postnatally

Group B streptococcus

The risk factors for neonatal group B streptococcus infection are shown in Table 12.4. Women with any of these risk factors should be treated with intrapartum high-dose intravenous penicillin (3 grams stat followed by 1.5 grams every 4 hours) or 8-hourly clindamycin 900 mg (if penicillin-allergic).

Table 12.4 The maternal risk factors for neonatal group B streptococcus (GBS) infection and indications for antibiotic prophylaxis

| Previous GBS-affected baby |

| Colonization with GBS at any time in the current pregnancy |

| GBS bacteriuria in the current pregnancy |

| Preterm labour (< 37 weeks) |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes |

| Pyrexia in labour |

Maternal systemic disorders

Haematological disorders

Anaemia

Anaemia is the commonest medical disorder of pregnancy.

Clinical features

Pallor, pale nails and pale conjunctivae as well as tachycardia may be noted on examination.

Investigations

Pregnant women may have a mixed folate and iron-deficiency picture.

Haemoglobinopathy screen should be checked if not done at booking.

Venous thromboembolism

Risk factors

Risk factors for VTE are shown in Table 12.5.

Table 12.5 Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperium

| Pre-existing risk factors: |

|---|

| Previous venous thromboembolism |

| Age over 35 years |

| Smoking |

| Obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2 at booking) |

| Parity > 4 |

| Gross varicose veins |

| Paraplegia |

| Congenital thrombophilia |

| antithrombin deficiency |

| protein C deficiency |

| protein S deficiency |

| factor V Leiden |

| Acquired thrombophilia |

| antiphospholipid syndrome |

| Thrombocythaemia |

| Polycythaemia |

| Sickle-cell disease |

| Inflammatory disorders, e.g. inflammatory bowel disease |

| Other systemic disease, e.g. nephrotic syndrome, cardiac disease |

| Risk factors developing during pregnancy: |

| Hyperemesis |

| Dehydration |

| Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| Long-haul travel |

| Severe infection, e.g. pyelonephritis |

| Immobility (> 4 days’ bed rest antenatally, intrapartum or postnatally) |

| Surgical procedure in pregnancy or puerperium, e.g. caesarean section, evacuation of retained products of conception, postpartum sterilization |

| Pre-eclampsia |

| Excessive blood loss |

| Prolonged labour |

| Midcavity instrumental delivery |

| Immobility after delivery |

Pathophysiology

Virchow’s triad describes the pathophysiological factors contributing to thrombus development:

VTE prophylaxis during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum

All women should be encouraged to mobilize early after delivery and keep well hydrated.

Additional measures such as thromboembolic stockings and prophylactic heparin should be considered after delivery for women with other significant risk factors. Generally, all women with three or more existing risk factors from Table 12.5 should be given LMWH prophylaxis for 3–5 days following delivery. However, age over 35 and obesity are particularly significant risks and prophylaxis should be considered for women who have both risk factors.

Pneumatic boots are another method of reducing VTE risk associated with caesarean section.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

and the presence (on two samples, at least 6 weeks apart) of:

Thrombocytopenia

Up to 10% of women have a low platelet count in pregnancy, most commonly due to gestational thrombocytopenia. The causes of thrombocytopenia are shown in Table 12.6.

| Common causes: |

|---|

| Gestational thrombocytopenia |

| Autoimmune idiopathic thrombocytopenia |

| Uncommon causes: |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related |

| Drug-induced thrombocytopenia |

| Pre-eclampsia |

| Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

Endocrine disorders

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Incidence

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) affects 4 in 1000 pregnant women.

| Maternal risks: |

| Difficult glycaemic control and increased hypoglycaemic episodes |

| Occasional diabetic ketoacidosis (e.g. with undercurrent infection, hyperemesis, steroids or tocolytics) |

| Worsening of diabetic retinopathy |

| Worsening of diabetic nephropathy |

| Increased risk of pre-eclampsia (especially with pre-existing hypertension or nephropathy) |

| Increased risk of infections |

| Fetal risks: |

| Congenital abnormality (5–25%) |

| Miscarriage |

| Infection (Candida, urinary tract infection, wound infection, endometritis) |

| Preterm delivery (20% risk) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction |

| Macrosomia |

| Polyhydramnios |

| Shoulder dystocia |

| Cord prolapse |

| Sudden intrauterine death |

| Neonatal risks: |

| Neonatal hypoglycaemia |

| Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome |

| Jaundice |

| Polycythaemia |

| Increased neonatal mortality |

Management

Prepregnancy

Prepregnancy consultation, as discussed in Chapter 11, is crucial for diabetic women as tight glycaemic control prior to pregnancy reduces the risk of fetal congenital abnormality and miscarriage. The number of insulin injections may be increased and a different combination of short- and longer-acting insulins used to maintain the blood glucose between 4 and 5 mmol/l. Non-insulin-dependent diabetics are usually converted from oral hypoglycaemic agents to insulin.

Gestational diabetes mellitus

Diagnostic criteria

• 2-hour venous glucose < 7.8 mmol/l: normal

• 2-hour venous glucose 7.8–11 mmol/l: impaired glucose tolerance

Renal disorders

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

The risk to the mother is pyelonephritis (1.8–28%) and to the fetus is preterm birth (2.1–12.8%).

Urinary tract infection

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed on MSU culture and the usual causative organism is Escherichia coli.

Neurological disorders

Epilepsy

Management

Preconceptual management is outlined in Chapter 11. Folic acid 5 mg daily should be continued throughout the pregnancy because of the risk of folate deficiency in the mother as well as neural tube defects in the fetus.

Liver disorders

Obstetric cholestasis

Clinical features

Women present with severe itching, especially on the limbs, trunk, palms and soles.

Cardiac disease

Pathophysiology

The changes in maternal physiology that affect cardiac disease in pregnancy are:

• Catecholamine release from pain and anxiety at delivery

• Sudden increase in blood volume at delivery (about 500 ml) as the uterus contracts

• The presence of pulmonary hypertension

• The New York Heart Association functional class (degree of breathlessness/exercise tolerance).

Table 12.8 gives a classification of cardiac disease in pregnancy according to maternal risk.

Table 12.8. Cardiac disease according to maternal risk in pregnancy

| High-risk (mortality up to 50%): |

|---|

| Eisenmenger’s syndrome |

| Tetralogy of Fallot |

| Transposition of the great vessels |

| Pulmonary hypertension (primary or secondary) |

| Ischaemic heart disease |

| Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy |

| Severe aortic stenosis |

| Moderate-risk (mortality up to 15%): |

| Valve stenosis |

| Coarctation of the aorta |

| History of myocardial infarction |

| Marfan’s syndrome |

| Mechanical prosthetic valve |

| Low-risk (mortality around 1%): |

| Valve regurgitation |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Uncomplicated ventriculoseptal defect/atrioseptal defect/patent ductus arteriosus |

| Porcine valve replacement |

Management

Prepregnancy counselling

This is discussed in Chapter 11. Women should be assessed for the nature and severity of the lesion and the risk to mother and fetus during a potential pregnancy should be discussed.

Specific cardiac diseases

Mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis is caused by rheumatic fever and is the commonest acquired heart disease.

Summary

• Half of pregnant women experience nausea or vomiting, but hyperemesis gravidarum, with excessive symptoms, occurs in only 1%.

• Thiamine replacement should always be included with fluids and antiemetics in the management of hyperemesis, to avoid the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

• Hypertension diagnosed prior to 20 weeks’ gestation is generally due to pre-existing chronic hypertension, rather than pregnancy-induced hypertension.

• Ten per cent of pregnant women develop hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia and 10% of these develop severe pre-eclampsia.

• Pre-eclampsia may be diagnosed by a combination of fetal and maternal features, including IUGR, haematological or biochemical abnormalities, as well as clinical symptoms and signs.

• Treatment of hypertension in pregnancy is important to reduce the risk of cerebrovascular accident, but does not alter the development of, and may mask, underlying pre-eclampsia.

• Women with confirmed pre-eclampsia should be managed as inpatients, because of the risk of fulminating disease or placental abruption.

• Vertical transmission of HIV can be reduced to less than 5% by zidovudine prophylaxis to the mother and baby, elective caesarean section and the avoidance of breastfeeding.

• Maternal group B streptococcal infection is an important cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, and prophylaxis protocols should be adhered to.

• VTE is still the leading cause of maternal mortality.

• Some cardiac diseases, such as Eisenmenger’s syndrome, carry a very high maternal mortality risk, and termination of pregnancy should be seriously considered in such cases.