Chapter 5 Physiological and anatomical changes in pregnancy

HORMONAL CHANGES

Most of the anatomical changes that occur in pregnancy are due to the hormones secreted by the placenta. These hormones and their effects on the woman’s body are described in Chapter 3. In addition, other endocrine glands synthesize hormones, in different quantities during pregnancy compared with the non-pregnant state. These changes are briefly described below.

GENITAL TRACT CHANGES

Uterus

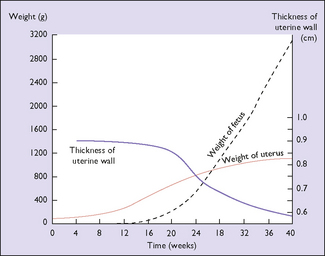

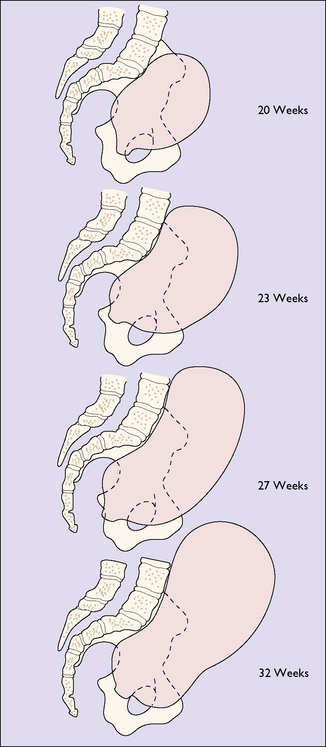

The effect of the hormonal stimulation is most marked upon the tissues of the genital tract, and the uterine muscle fibres grow to 15 times their prepregnancy length during pregnancy, whereas uterine weight increases from 50 g before pregnancy to 950 g at term (Fig. 5.1). In the early weeks of pregnancy the growth is by hyperplasia, and more particularly by hypertrophy of the muscle fibres, with the result that the uterus becomes a thick-walled spherical organ. From the 20th week growth almost ceases and the uterus expands by distension, the stretching of the muscle fibres being due to the mechanical effect of the growing fetus. With distension the wall of the uterus becomes thinner and the shape cylindrical (Fig. 5.2). The uterine blood vessels also undergo hypertrophy and become increasingly coiled in the first half of pregnancy, but no further growth occurs after this, and the additional length required to match the continuing uterine distension is obtained by uncoiling the vessels.

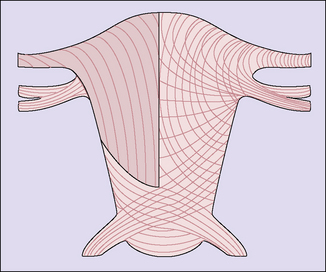

The effect of the uterine distension is to stretch both interdigitating spiral systems and to increase the angle of crossing of the fibres, in the thinner lower segment area where the fibres cross at an angle of about 160 ° and are less stretched. Incision of the myometrium in this zone is anatomically more suitable, and experience of lower segment caesarean section confirms that healing is better (Fig. 5.3).

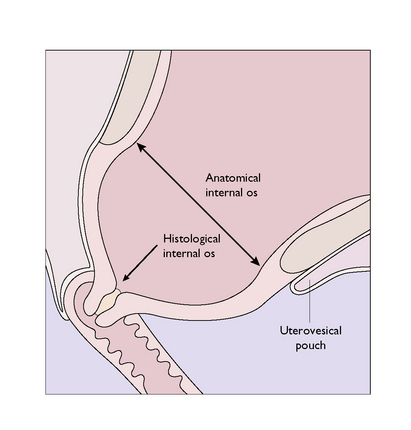

The lower uterine segment is that part of the lower uterus and upper cervix lying between the line of attachment of the peritoneum of the uterovesical pouch superiorly and the histological internal os inferiorly. It is that part of the uterus where the proportion of muscle diminishes, this muscle being replaced increasingly by connective tissue (mainly collagen fibres), which forms 90% of the cervical tissues (Fig. 5.4). Because of this the lower uterine segment becomes stretched in late pregnancy as the thickly muscled fundus draws it up from the relatively fixed cervix.

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

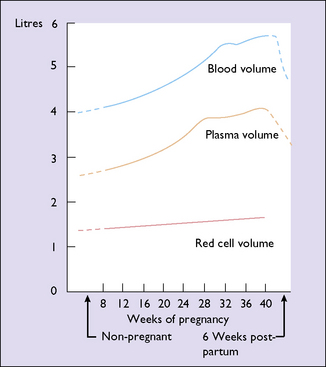

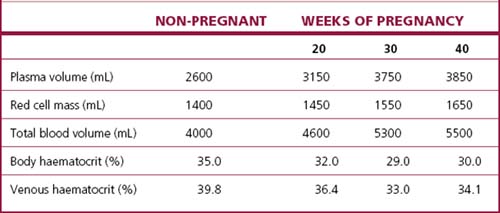

The changes that occur during pregnancy to the blood volume, the plasma volume and the red cell mass are shown in Figure 5.5 and Table 5.1. The plasma volume increases to fill the additional intravascular space created by the placenta and the blood vessels. The red cell mass increases to meet the increased demand for oxygen. Because the increase in the red cell mass is proportionately less than the increase in the plasma volume, the concentration of the erythrocytes in the blood falls, with a reduction in the haemoglobin concentration. Although the haemoglobin concentration falls to about 120 g/L at the 32nd week, a larger total haemoglobin is present than when not pregnant. Concurrently the number of white blood cells increases (to about 10 500/mL), as does the blood platelet count.

Cardiovascular dynamics

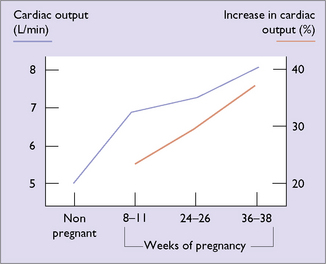

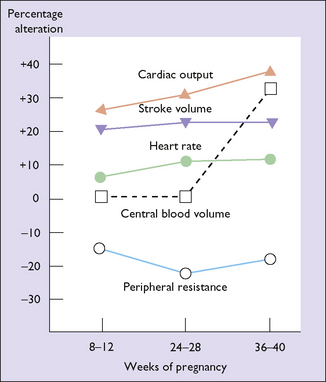

To deal with the increased blood volume and the additional demand for oxygen in pregnancy the cardiac output increases by 30–50% (Fig. 5.6). Most of the increased output is due to an increased stroke volume, but the heart rate increases by about 15%. The increased cardiac output is balanced by a decrease in the peripheral resistance (Fig. 5.7). For these reasons, blood pressure falls in early pregnancy rising back to prepregnancy levels by the third trimester.

WEIGHT GAIN IN PREGNANCY

Elements of weight gain in pregnancy

Weight gain in pregnancy is caused by several factors:

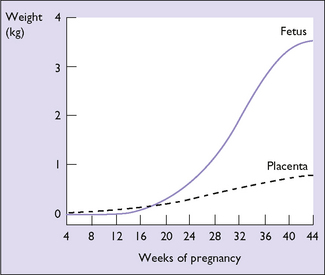

Fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid

In the first 20 weeks of pregnancy fetal weight gain is slow; in the second 20 weeks it increases more rapidly. The weight gain of the placenta shows the reverse of that of the fetus (Fig. 5.8). The amniotic fluid increases rapidly from the 10th week, being 300 mL at 20 weeks, 600 mL at 30 weeks, and peaking at 1000 mL at 35 weeks. After this a small decline in the total quantity of amniotic fluid occurs.

Maternal factors

The weight of the uterus increases throughout pregnancy. It is more rapid in the first 20 weeks, when myohyperplasia is occurring, than in the second 20 weeks when most of the enlargement is due to stretching of the muscle fibres. The breasts increase in weight throughout pregnancy owing to deposition of fat, increased retention of fluid, and growth of the glandular elements. The blood volume also increases throughout the pregnancy (see Fig. 5.5). The amount of fat deposited in adipose tissues depends on the amount of fat and carbohydrate in the diet. A gain of 2.5–3.0 kg of fat is usual, of which 90% is deposited in the first 30 weeks. The fat contains 90–105 MJ of energy, which can be released after birth for various activities, including breastfeeding. In a normal pregnancy the total body fluid increases by 6–8 L, of which 2–4 L is extracellular. Most of the fluid is retained before the 30th week, but a pregnant woman who has no clinical oedema retains 2–3 L of extracellular fluid in the last 10 weeks of pregnancy.

The elements of weight gain in pregnancy and their weight at 40 weeks are shown in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 The elements of weight gain (g) in pregnancy at 40 weeks

| Increasing Element | Weight Gain (g) |

|---|---|

| Fetus | 3300 |

| Placenta | 600 |

| Uterus | 900 |

| Breasts (glandular tissue) | 400 |

| Blood | 1200 |

| Fat deposited | 2500 |

| Fluid (extracellular) | 2600 |

| Total | 11000 |