Chapter 7 Physiological and anatomical changes in childbirth

THE PASSAGES

Bony pelvis

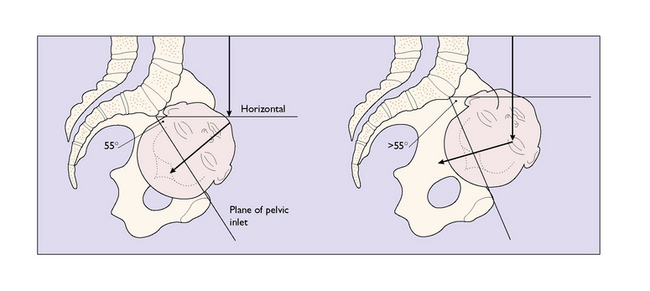

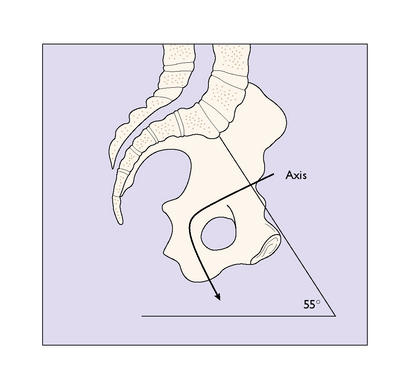

The bony pelvis is made up of four bones, the two innominate bones, the sacrum and the coccyx, united at three joints. When a woman stands erect, the pelvis is tilted forward. The pelvic inlet makes an angle of about 55 ° with the horizontal. The angle varies between individuals and between races; for example, black Africans have a lesser angle. An angle of more than 55 ° may make the descent of the fetal head into the pelvis difficult (Fig. 7.1).

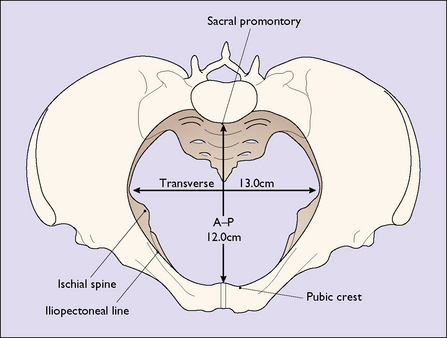

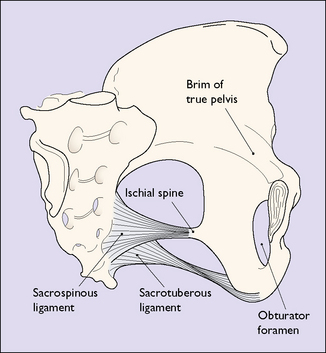

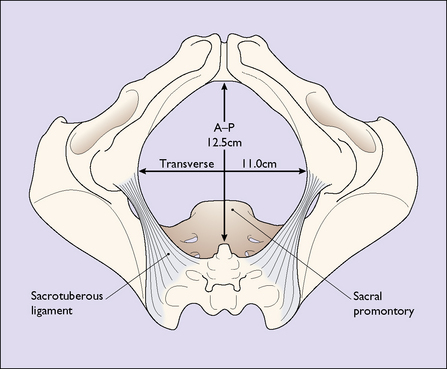

The ‘true’ pelvis is bounded by the pubic crest, the iliopectineal line and the sacral promontory. An ‘ideal obstetric’ pelvis is described in Box 7.1 and the brim is shown in Figure 7.2. The true pelvis is cylindrical in shape, with a bluntly curved lower end, and is slightly curved anteriorly. Anteriorly the pubic bones form its boundary, measuring 4.5 cm. Posteriorly, the curve of the sacrum forms its boundary, measuring 12 cm. Laterally its walls narrow slightly distally (Fig. 7.3). The walls are penetrated by the obturator foramen anteriorly and the sciatic foramen laterally, which is divided into two parts by the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

Box 7.1 The ideal obstetric pelvis

| Brim | Round or oval transversely |

| No undue projection of the sacral promontory | |

| Anterior–posterior diameter 12 cm | |

| Transverse diameter 13 cm | |

| The plane of the pelvic inlet not less than 55 ° | |

| Cavity | Shallow with straight side-walls |

| No great projection of the ischial spines | |

| Smooth sacral curve | |

| Sacrospinous ligament at least 3.5 cm | |

| Outlet | Pubic arch rounded |

| Subpubic angle > 80 ° | |

| Intertuberous diameter at least 10 cm |

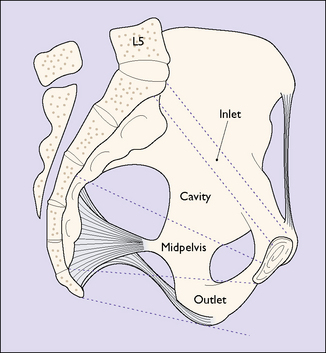

For descriptive purposes the true pelvis can be divided into four zones. These are shown in Figure 7.4. The measurements of the zone of the inlet are shown in Figure 7.2. The zone of the cavity is wedge-shaped in profile and almost round in section. It is the most roomy part of the true pelvis, the anterior–posterior diameter measuring 13.5 cm and the transverse diameter 12.5 cm.

The zone of the outlet (Fig. 7.5) does not usually interfere with the birth unless the pubic rami are narrow, which reduces the intertuberous diameter. In these cases delay may occur and the soft tissues of the perineum may be torn and damaged.

The axis of the birth canal corresponds to the direction the fetal presenting part – usually the head – takes during its passage through the birth canal (Fig. 7.6).

Soft tissues of the female pelvis

These include the uterus, the muscular pelvic floor and the perineum. The anatomical details are described in Chapter 43.

Uterus

The uterus in pregnancy can be divided into three parts:

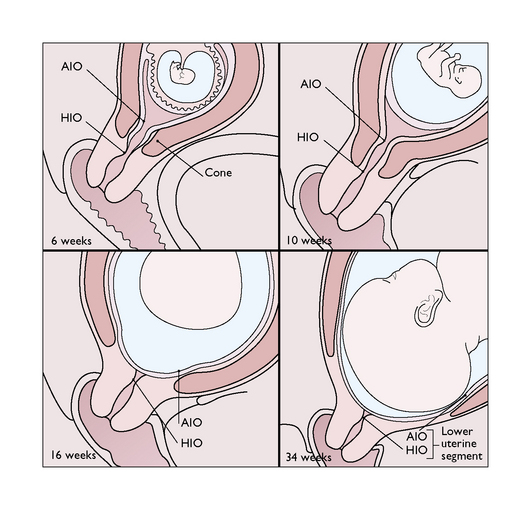

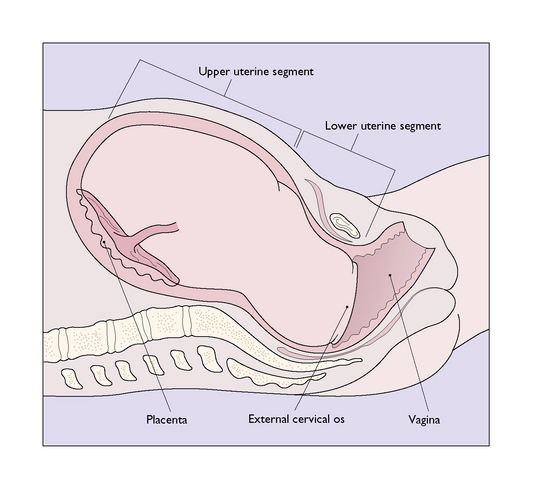

Lower uterine segment

This portion of the uterus lies between the vesico-uterine fold of the peritoneum superiorly and the cervix inferiorly. During pregnancy the upper part of the cervix is incorporated into the lower uterine segment, which stretches to accommodate the fetal presenting part (Fig. 7.7). In late pregnancy, as the upper segment muscle contractions increase in frequency and strength, the lower uterine segment develops more rapidly and is stretched radially to permit the fetal presenting part to descend (Fig. 7.8). In labour the entire cervix becomes incorporated into the stretched lower uterine segment.

Cervix uteri

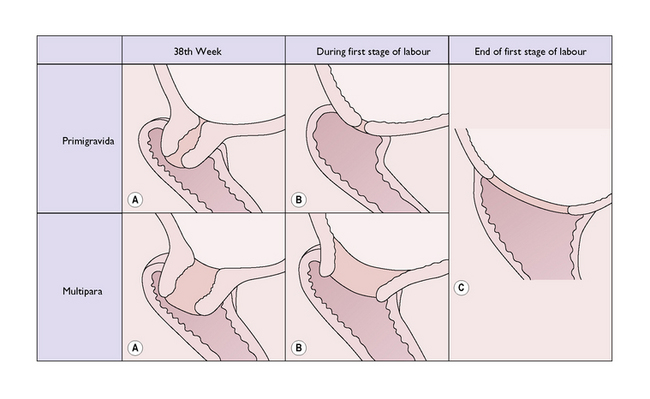

In late pregnancy the cervix becomes softer because of chemical changes in the collagen fibres, and shorter as it is incorporated into the lower uterine segment. It also undergoes a variable degree of dilatation. Collectively, these changes are termed cervical ‘ripening’. The changes may occur abruptly or gradually at any time after the 34th week of pregnancy, but usually occur nearer term, especially in primigravidae. At the 34th gestational week the cervix is 2 cm or more dilated in 20% of primigravidae and in 40% of multigravidae, and the proportion increases towards term (Fig. 7.9).

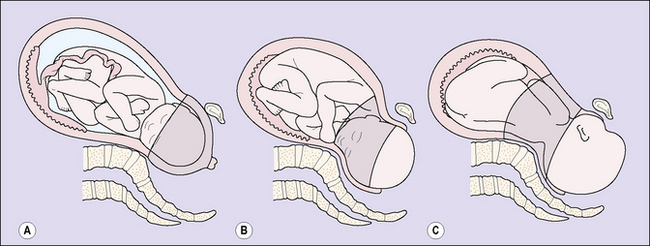

Formation of the birth canal during labour

When myometrial contraction and retraction have led to full dilatation of the cervix the fetal head descends into the vagina, which expands to encompass it (Fig. 7.10). Normally an apparent space, the vaginal muscle has hypertrophied and the epithelium become folded during pregnancy so that it can accommodate the fetus without damage. As the fetal head descends it encounters the pelvic floor and the leading point is directed forwards by the gutter formed by the levatores ani. The fetus must now pass through the urogenital diaphragm. The levator muscles stretch and are displaced downwards and backwards, so that the anus receives the full force of the descending head and, dilating, gapes widely to expose the anterior rectal wall. Pressure is also exerted on the lower part of the vagina and the central portion of the perineum, and as the head is born the tissues may tear.

THE PASSENGER

Anatomy of the fetal skull

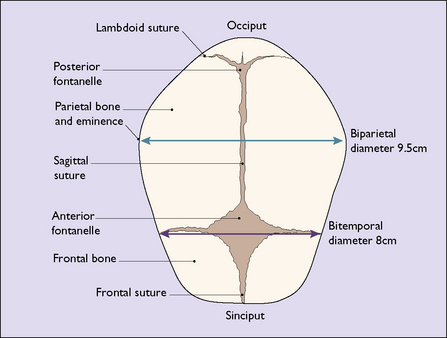

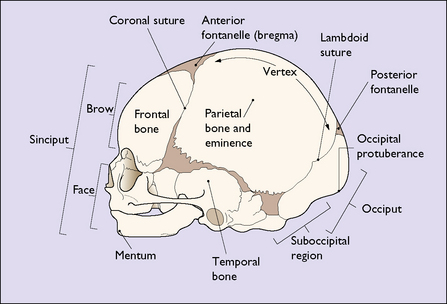

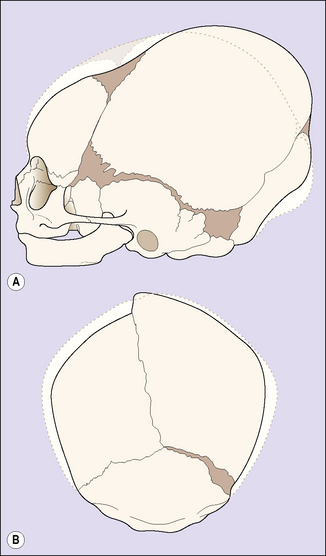

The face of the term fetus is relatively small in relation to the cranium, which makes up most of the head. The cranium is made up of five bones held together by a membrane, which permits their movement during birth and in early childhood. The bones are the two parietal bones, the two frontal bones and the occipital bone (Fig. 7.11). The membranous areas between the bones are called sutures. The coronal suture separates the frontal bones from the parietal bones. The sagittal suture separates the two parietal bones, and the lambdoid suture separates the occipital bone from the parietal bones (Fig. 7.12). The anterior fontanelle is the diamond-shaped area of the junction of the sagittal and the two coronal sutures. The posterior fontanelle is the smaller Y-shaped area at the junction between the sagittal suture and the two lambdoid sutures. The configuration of the posterior fontanelle permits the occipital bone to be displaced under the two parietal bones during childbirth, thus reducing the volume of the fetal skull. This is called moulding. During moulding, the parietal bones may also slip under each other (Fig. 7.13).

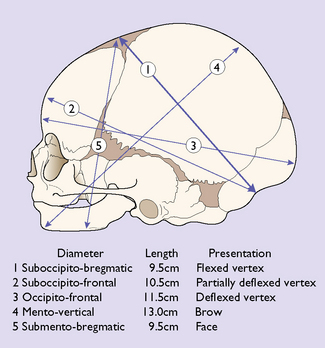

The region of the skull that presents in labour depends on the degree of flexion of the head. The diameters are shown in Figure 7.14, along with degrees of flexion or deflexion of the head on presentation to the maternal pelvis.

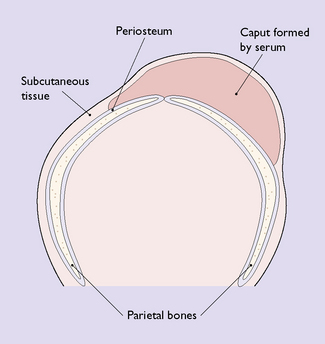

In labour, after the amniotic sac has ruptured, releasing amniotic fluid, the dilating cervix may press firmly on the fetal scalp, reducing both lymphatic and venous return from it. This may cause a tissue swelling beneath the skin called a caput succedaneum (Fig. 7.15). It is soft and boggy to the touch and disappears within a few days of birth.

THE POWERS

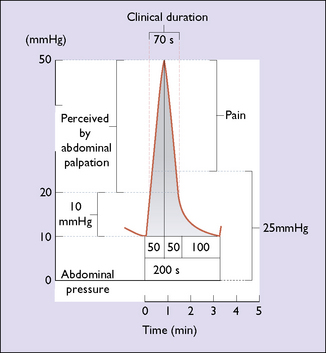

Characteristics of myometrial contractions

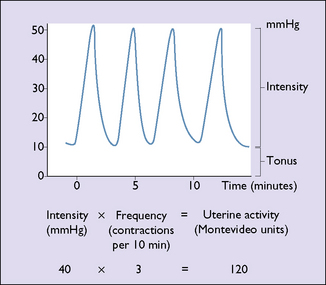

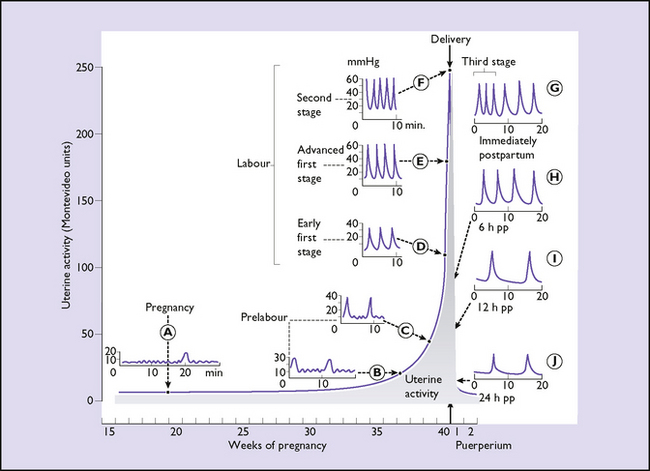

The uterus, although composed of many individual muscle fibres, functions as a single hollow muscular organ. The myometrium is never completely relaxed. It has a resting tone of between 6 and 12 mmHg. From early until late pregnancy the uterus contracts at intervals; the contractions (Braxton Hicks contractions) are painless. Each contraction causes a rise in intrauterine pressure of varying amplitude or intensity. This has two elements: a rapid rise to a peak and a slower return to the resting tone. For descriptive purposes the intensity of the contraction multiplied by the frequency of the contractions (per 10 minutes) provides a measure of uterine activity, which is expressed in Montevideo units (Fig. 7.16). With the development of tocography, a different measure of uterine activity can be obtained. With a cardiotocograph linked to a computer, the area under the contraction can be measured and expressed in kilopascals per 15 minutes. These two methods of measuring uterine activity relate fairly closely to each other.

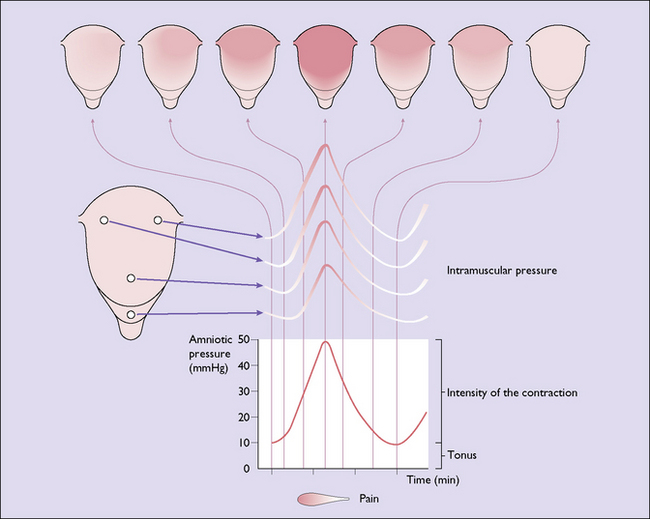

Spread of uterine contractions

A uterine contraction starts from a pacemaker located at the junction of the Fallopian tube and the uterus on one side. The contractile wave passes inwards and downwards from the pacemaker at a rate of 2 cm per second to involve the entire uterus in the contraction. In a normal labour the intensity and incremental phase of the contraction is greater in the upper uterine segment, as the muscle is thicker and there is a greater amount of actinomyosin to contract. This permits the contraction to be coordinated, the maximal intensity occurring in the upper part of the uterus, with a reducing intensity as the wave passes down towards the cervix; the peak of the contraction occurs simultaneously in all parts of the uterus. The phenomenon is known as the triple descending gradient (Fig. 7.17).

Myometrial activity in pregnancy and labour

Pregnancy

Up to the 30th week of pregnancy uterine activity is slight, small localized contractions of no more than 5 mmHg occurring at intervals of 1 minute. Every 30–60 minutes a contraction of higher amplitude (10–15 mmHg) arises which spreads to a wider area of the uterus and may be palpated (Fig. 7.18A). These palpable contractions occur with increasing frequency and intensity after the 30th week and are referred to as Braxton Hicks contractions (Fig. 7.18B). After the 36th week uterine activity increases progressively until labour starts (Fig. 7.18C).

Onset of labour

This is difficult to determine with accuracy, and consequently difficult to define. At best it can be said to be the time after which uterine contractions cause the progressive dilatation of the cervix beyond 2 cm, and painful contractions usually occur at least every 10 minutes (Fig. 7.18D).

Labour

In true normal labour the intensity and frequency of the contractions increase, but there is no rise in the resting tone. The intensity increases in late labour to 60 mmHg and the frequency to two to four contractions every 10 minutes, or 150–200 Montevideo units. The duration of the contraction also increases from about 20 seconds in early labour to 40–90 seconds at the end of the first stage, and in the second stage (see Fig. 7.18E). Contractions are most effective when they are coordinated, with fundal dominance, have a maximum intensity of 40–60 mmHg, last 60–90 seconds, recur with a 2–4-minute interval between the peaks of consecutive contractions, and the uterus has a resting tone of less than 12 mmHg. More frequent contractions of higher intensity diminish the oxygen exchange in the placental bed and may lead to fetal hypoxia and clinical signs of fetal distress. The efficiency of contractions is greater when the mother walks about or lies on her side during the first stage of labour, and this position also improves the placental blood supply.

In the second stage of labour, voluntary contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, added to the uterine contraction, propels the baby downwards through the dilated vagina and overcomes the resistance of perineal muscles to its advance (see Fig. 7.18F). At the height of each bearing-down effort the total force exerted on the fetus is approximately 2 kg/cm2 and this is resolved into two components: one, a force propelling the head downwards, and the other, a dilating force, which stretches the birth canal against the resistance of the pelvic and perineal muscles. (If the membranes are intact the resultant propelling force is less, as the amniotic fluid balances it in part.) Because the pelvic floor muscles form an inclined groove, and as the head is ovoid, the additional pressure leads to the rotation of the occiput through 90 ° to lie anteriorly.

Uterine activity continues unaltered after expulsion of the fetus and leads to the expulsion of the placenta from the upper uterine segment, between 2 and 6 minutes after the birth of the baby. Once the placenta has left the upper segment uterine activity diminishes, but contractions of an intensity of about 60–80 mmHg still occur regularly for 48 hours after delivery, the frequency decreasing as time passes (see Fig. 7.18G–J). These contractions, and those of the third stage, are usually painless, but painful contractions disturb some patients. Further painful contractions may occur with suckling, owing to a reflex release of oxytocin.

Pain of uterine contractions

The pain of uterine contractions is, in part, due to ischaemia developing in a myometrial fibre. Because there are more fibres and the contractions are stronger in the upper uterine segment, pain is felt more strongly in the cutaneous distribution of cutaneous nerves T12 and L1. At the beginning of the contraction only slight pain is felt; it increases as the contraction grows stronger (Fig. 7.19).