Physical examination procedures

9.1 Differential diagnosis information from other assessments

9.1.1 Observations and symptoms

(a) Simple observation of the patient’s physical features can be useful. For example, obesity is a risk factor for hypertension and carotid artery disease.

(b) A palpable preauricular node can be helpful information in determining the cause of a red eye. In addition, differential diagnosis of the cause of the red eye can begin in the case history with questions regarding the duration, recurrence and laterality of the red eye, any discomfort and type of discharge.

(c) While mild to moderate hypertension does not cause headache, the presence of pulsating, suboccipital headaches that subside during the day, particularly in an older patient, may suggest acute hypertension and thus the need for sphygmomanometry.1

(d) Episodes of transient loss of vision (amaurosis fugax) may be present in carotid artery stenosis which requires further investigation. Amaurosis fugax is a sudden onset, painless loss of vision in one eye that is described as a curtain coming down over the vision. The vision loss generally lasts longer than one minute.2

9.1.2 General medical history and family history

The medical history in a patient with a red eye may be important in the differential diagnosis. For example, a history of a recent upper respiratory tract infection and contact with another person with a red eye could be suggestive of viral origin to the red eye, the history of a urogenital infection could be suggestive of Chlamydia, a history of cold sores is suggestive of herpes simplex virus conjunctivitis and a history of allergy with intensive itching is suggestive of allergic conjunctivitis.3

A history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, obesity, physical inactivity, heavy alcohol intake, smoking, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia are important when considering if blood pressure measurement is indicated. When there is a positive family history the risk of developing hypertension is increased two to four times.4 The patient’s medical history should also include the current medical care for systemic conditions, frequency of monitoring for the conditions, previous and planned investigations for the conditions, medications prescribed and compliance with medication use. For example, if a patient has been diagnosed as hypertensive, is taking medication regularly and having their blood pressure regularly monitored, then there would be little need for optometric testing. If, however, the patient was previously diagnosed with hypertension, stopped taking their medication 6 months ago due to an adverse reaction and has not seen their physician to follow up, it would be prudent to take a blood pressure reading and advise the patient accordingly even in the absence of abnormalities on the ocular fundus examination.

9.1.4 Fundus examination

Ocular fundus features suggesting hypertension and the possible need for sphygmomanometry are discussed in section 9.3 and Table 9.1. Ocular risk factors for significant carotid artery stenosis include emboli (Hollenhorst plaques), retinal vascular occlusions, peripheral retinal haemorrhages with dilated and tortuous veins (hypoperfusion retinopathy), microrubeosis iridis, ocular ischaemic syndrome, anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, normal tension glaucoma and asymmetric diabetic retinopathy which is less advanced ipsilateral to the stenosis.5,6

Table 9.1

Simplified classification of hypertensive retinopathy as proposed by Wong and Mitchell17

| Grade of retinopathy | Retinal signs | Systemic associations |

| None | No detectable signs | None |

| Mild | Generalised arteriolar narrowing, focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, opacity (‘copper wiring’) of arteriolar wall, or a combination of these signs | Modest association with risk of clinical stroke, subclinical stroke, coronary heart disease, and death |

| Moderate | Haemorrhage (blot, dot, or flame-shaped), microaneurysm, cotton-wool spot, hard exudate, or a combination of these signs | Strong association with risk of clinical stroke, subclinical stroke, cognitive decline, and death from cardiovascular causes |

| Malignant | Signs of moderate retinopathy plus swelling of the optic disc | Strong association with death |

9.2 Lymphadenopathy in the head–neck region

9.2.1 The lymph nodes in the head and neck

The lymph nodes are situated along the course of the lymphatic vessels. They are bean-shaped organs containing large numbers of leukocytes and phagocytes which filter out infectious and toxic material and destroy it. When infection occurs the nodes become enlarged and often painful and inflamed because of the production of anti-inflammatory lymphocytes and plasma cells.7

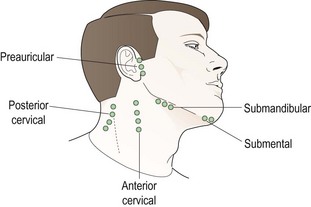

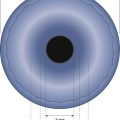

The lymphatic system of the head and neck is important in infections of the eye (Figure 9.1), particularly the preauricular lymph nodes which receive lymph from the upper eyelid, the outer half of the lower eyelid and the lateral canthus. They are located 1 cm anterior and slightly inferior to the tragus of the external ear at the temporomandibular joint. The submandibular lymph nodes lie in close proximity to the submandibular gland and drain lymph from the medial portion of the upper and lower eyelids, the medial canthus and the conjunctiva. They also drain lymph from the submental nodes that are located under the tip of the chin. The mental nodes also drain anterior aspects of teeth, tongue and lower lip so if an oral infection is present then they may be enlarged and this should not be mistaken for a sign of an ocular infection. The superior cervical nodes are located inferior to the ear and superficial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. They receive lymph from the occipital nodes as well as the preauricular and post auricular nodes.7 The skin and orbicularis oculi muscles drain into the deep cervical nodes near the internal jugular vein (Figure 9.1).

9.2.3 Procedure for palpating the preauricular lymph nodes

1. Wash your hands thoroughly.

2. Stand in front of the seated patient.

3. Place the index and middle fingers of each hand in front of the tragus of the patient’s external ears.

4. Slowly move your fingers in a circular motion to slide the patient’s skin over the underlying bony structures of the temporo-mandibular joint and search for swollen lymph nodes. These will feel like a small pebble or bean under the patient’s skin. A slight depression of the joint is the normal finding.

5. Compare the right and left sides to help determine whether a swollen node is present.

6. If lymphadenopathy is found, its laterality (right, left or bilateral), size (big or small), mobility, warmth and tenderness should be determined.

9.2.4 Procedure for palpating the cervical, submandibular and submental lymph nodes

1. All these lymph nodes are in the neck area (Figure 9.1) and should be palpated using the tips of your index, middle and ring fingers of both hands (the submental can be palpated using just one hand). Slowly move your fingers in a circular motion to slide the patient’s skin over the underlying bony structures and/or muscle and search for swollen lymph nodes, which will feel like a small pebble or bean under the patient’s skin.

2. In each case, if lymphadenopathy is found, its laterality (right, left or bilateral if appropriate), size (big or small), mobility, warmth and tenderness should be determined.

3. To assess the cervical nodes, palpate at the angle of the jaw and slowly move your fingers down, continuing to palpate to the base of the neck.

4. To assess the submandibular nodes, palpate just under the edge of the jawbone.

5. To assess the submental lymph nodes, palpate under the tip of the chin.

9.2.6 Interpretation

1. Viral conjunctivitis: visible preauricular lymphadenopathy often greater on the side of the more involved eye and accompanied by ear, nose and throat symptoms.

2. Severe bacterial lid conditions such as preseptal cellulitis or infection in the medial canthal region: preauricular or submental lymphadenopathy.

3. Parinaud’s oculoglandular conjunctivitis: often visible preauricular lymphadenopathy.

4. Chlamydial conjunctivitis or trachoma: preauricular lymphadenopathy.

5. Following the resolution of an ocular infection (several weeks).

The presence of preauricular lymphadenopathy will therefore help rule in one of the above conditions when it is present although if it is not present the condition cannot be reliably ruled out.8,9 An awareness of the areas that the nodes drain is also important to rule out other causes of enlargement of the nodes. For example, if the submental and the submandibular nodes are swollen the infection could be in the area drained by the submental nodes such as infections of the teeth, tongue and lower lip. This should be ruled out in the case history.

9.3 Blood pressure measurement

Hypertension is the most common cause of mortality in the developed world as a major contributing factor in stroke, heart attack, coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease.10 Hypertension affects about 25% of adults and over 50% of people aged 65+ in Canada and the UK and over 60 million Americans, with varying prevalence throughout the world.11–14 Systemic hypertension can be classified as primary (which has no known cause, 90–95%) or secondary (where the causative factor could be renal or endocrine disease or coarctation of the aorta, 5–10%).10 Early hypertension is often asymptomatic but in acute cases, the patient may complain of suboccipital pulsating headaches that occur early in the morning and subside during the day or any other type of headache.1 Somnolence, confusion, visual disturbances, and nausea and vomiting are only present in hypertensive emergencies (BP >180/120).15

Systemic hypertension is associated with hypertensive retinopathy and also choroidopathy, optic neuropathy, arterial and venous occlusive disease, embolic events and arteriolar macroaneurysm formation.16 Wong and Mitchell proposed a simplified classification of hypertensive retinopathy that combined the Keith–Wegener–Barker classification of stage I and II into a ‘mild’ category (Table 9.1).17

If blood pressure is measured in patients who show moderate to malignant fundus signs of hypertensive retinopathy the blood pressure reading will allow the practitioner to determine if it is an emergency needing to be sent to the emergency department of a hospital or an urgency that would be best seen by the patients’ primary care physician (section 9.3.4).13 A history of uncontrolled hypertension (e.g., the person stopped taking their medication without follow-up) or a family history is also an indication for measuring blood pressure.

However, approximately 40% of people with hypertension are not on treatment and two thirds of patients on treatment are not being controlled to less than 140/90.15 Also, not all patients with hypertension develop retinopathy.18 Even after 10 years, 70% of patients show either no retinopathy or only slight constriction and arteriolosclerosis.10 In addition, the inter-rater reliability of detection and classification of hypertensive retinopathy with ophthalmoscopy has been shown to be poor.18,19 Barnard showed that referral made on fundus signs alone resulted in a 78% false positive rate after blood pressure was measured and considered in patients between 45 and 64 years.20 A survey by Wolffsohn et al. found that the majority of primary care physicians would appreciate receiving a report of their patients’ blood pressure if it was found to be over 140/90.18 Therefore, consideration can be given to screening for hypertension as part of a routine eye examination of older patients. What still needs to be researched is the impact of optometric referrals on the ultimate blood pressure management of the patient.

9.3.1 Comparison of sphygmomanometers

Most devices for measuring blood pressure occlude a blood vessel in an extremity (usually the arm, wrist or finger) with an inflatable cuff then measure the blood pressure either by detection of Korotkoff sounds or oscillometrically.21 In the auscultatory method a stethoscope is used on the brachial pulse to detect Korotkoff Phase I sound (the systolic blood pressure) and the cessation of the Korotkoff Phase V sounds (the diastolic pressure) on the deflation of the cuff. In this method the sphygmomanometer used to measure the pressure can be mercury, aneroid or electronic with a digital display. Mercury sphygmomanometers have a limited future due to concerns about toxicity of mercury for users, personnel and the environment.22 Aneroid devices are inexpensive and portable but the bellow-and-lever system used to measure pressure is subject to jolts and bumps which can lead to false readings.22 Aneroid devices require regular calibration and should be checked against a mercury sphygmomanometer every 6 months. Hybrid devices use an electronic pressure gauge and display.

An alternative to the auscultatory method are automated (oscillometric) sphygmomanometers, which are very simple and easy to use. They detect the variation in pressure oscillations caused by arterial wall movement under the cuff to measure systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure.23 Automated devices were designed for self-measurement and are increasingly used in clinical practice.24

Two recent systematic reviews have shown that automated devices have individual variability but are generally less accurate than auscultatory devices even when passing specified protocols.23,25 These devices should not be used in patients who have arrhythmia, hypertension or have had trauma. Since the devices may have poor reliability, multiple readings should be used and averaged when making clinical decisions.25 Thresholds for standard sphygmomanometry should not be applied to automated readings. The definition of hypertension when using these devices is the same as for ambulatory methods at normal being <135/85.24,26

9.3.2 Procedure for sphygmomanometry by the auscultatory method

1. Have the patient remain seated quietly with feet on the floor for at least 5 minutes before blood pressure readings are measured. Caffeine, smoking and exercise should have been avoided for 30 minutes prior to the blood pressure reading.15

2. Describe the procedure to the patient: ‘I am now going to measure your blood pressure. This involves wrapping a cuff around your arm and inflating it. You will feel the pressure on your arm increase, but you shouldn’t experience any pain.’

3. Ask the patient to remove any clothing covering the arm and ensure that any rolled up sleeve does not excessively constrict the arm.

4. Ask the patient to slightly bend their arm with the palm turned upwards and rest it on the chair armrest or nearby table. The arm should be at heart level.

5. Select a blood pressure cuff that encircles at least 80% of the arm to ensure accuracy.15 Typically two cuff sizes are required: large and regular adult.

6. Locate the brachial artery along the inner upper arm by palpation. Wrap the cuff smoothly and snugly around the arm, centering the bladder over the brachial artery (the artery arrow on the cuff should be pointing at the artery). The lower margin should be 2.5 cm above the antecubital crease (bend of the elbow).

7. Check that the cuff fits snugly, but is not too tight or too loose. If it is difficult to insert a finger under the cuff edge it is too tight, if you can insert more than one finger it is too loose.

8. Before measuring the blood pressure, you should palpate the systolic pressure to avoid an artificially low reading caused by auscultatory gap (see section 9.3.5). Palpate the radial pulse at the wrist and inflate the cuff by pumping the bulb until the pulse disappears then continue to inflate the cuff until the reading is approximately 30 mmHg over the point where the pulse first disappears. Deflate the cuff smoothly at a rate of 2–3 mmHg per second until the pulse is felt again and note this reading. Then deflate the cuff rapidly and completely.

9. Insert the earpieces of the stethoscope into your ears so that they angle forward and are comfortable. Position the stethoscope head over the brachial artery between the lower cuff edge and the antecubital crease. Turn the chestpiece of the stethoscope so that the diaphragm side is transmitting and place it over the artery with light pressure, ensuring skin contact at all points. Heavy pressure may distort sounds.

10. Rapidly and steadily inflate the cuff to 20–30 mmHg above the palpated systolic pressure value determined in Step 8. Release the air in the cuff by turning the manometer release valve to slowly and smoothly release air from the bladder at a rate of 2 to 3 mmHg per second.

11. Listen for the Korotkoff sounds (online audio 9.4)![]() . Note the systolic pressure at the onset of the first audible Korotkoff Phase I sound (soft tapping sounds). Determine the diastolic pressure at the cessation of the Korotkoff sounds (Phase V). Listen for 10 to 20 mmHg below the last sound heard to confirm disappearance, and then deflate the cuff rapidly and completely. Between Phases I and V are Phase II, which is a swishing, murmur, Phase III which is crisper sounds with increasing intensity and IV which is an abrupt muffling of sounds.

. Note the systolic pressure at the onset of the first audible Korotkoff Phase I sound (soft tapping sounds). Determine the diastolic pressure at the cessation of the Korotkoff sounds (Phase V). Listen for 10 to 20 mmHg below the last sound heard to confirm disappearance, and then deflate the cuff rapidly and completely. Between Phases I and V are Phase II, which is a swishing, murmur, Phase III which is crisper sounds with increasing intensity and IV which is an abrupt muffling of sounds.

12. If a repeat reading is required wait 1–2 minutes to permit the release of blood trapped in the forearm venous system.

9.3.4 Interpretation

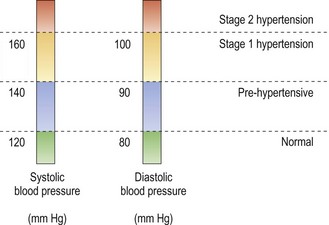

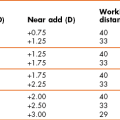

The classification of hypertension is based on two properly measured seated blood pressure readings on each of two or more separate office visits and is shown in Figure 9.2, although research suggests that ambulatory measurements better predict who should be placed on treatment.15,26 Individuals that are suspected to be in the pre-hypertensive classification should be referred to a general physician for health-promoting lifestyle modifications. These modifications include weight control, increase in physical activity, and reductions in salt intake and alcohol consumption and smoking cessation. Stage 1 and 2 hypertension should be referred to a general physician to be treated with pharmacological interventions with most patients needing two or more anti-hypertensive medications to achieve a blood pressure of less than 140/90.15

A hypertensive emergency occurs when the systolic blood pressure is greater than 210 mmHg and the diastolic greater than 130 mmHg. There is evidence of progressive or impending target-organ damage and the blood pressure must be lowered immediately but carefully to prevent end-organ damage from lowering the blood pressure too quickly. This treatment normally requires hospitalisation. A hypertensive urgency is an increase in diastolic blood pressure to greater than 120–130 mmHg without end-organ damage which can be treated in office or in the emergency room with oral medications over several hours to lower the blood pressure. This usually occurs in patients who discontinue their treatment after achieving normal blood pressure.15,27

9.3.5 Most common errors

1. Using the wrong cuff size: If you use too small a cuff for the size of the patient’s arm, it leads to excessive loss of pressure from the cuff through the thick and compressible soft arm tissue and a falsely high blood pressure reading can be gained. You need to select a blood pressure cuff that encircles at least 80% of the arm to ensure accuracy.15 Typically two cuff sizes are required in optometric practice: large adult and regular adult. Child size cuffs are also available, but unlikely to be used in optometric practice.

2. Ignoring the auscultatory gap: In some patients, particularly those with hypertension and when the cuff pressure is high, the sounds heard over the brachial artery disappear as the pressure is reduced and then reappear at some lower level. This early, temporary disappearance of sound is called the auscultatory gap and occurs during the latter part of Phase I and Phase II. Because this gap may extend over a range as great as 40 mmHg, you could seriously underestimate the systolic pressure or overestimate the diastolic pressure, if you fail to gain an initial estimate of the systolic pressure after palpating the radial pulse at the wrist.

3. Using an incorrect arm position: The pressure in the arm increases as the arm is lowered from the level of the heart (phlebostatic axis); conversely, raising the arm above this position lowers the pressure measurement. The effect is largely explained by hydrostatic pressure or by the effect of gravity on the column of blood. Therefore, when measuring indirect blood pressure, the patient’s arm should be positioned so that the location of the stethoscope head is at the level of the heart. This location of the heart is arbitrarily taken to be at the junction of the fourth intercostal space and the lower left sternal border. When the patient is seated, placing the arm on a nearby tabletop a little above waist level will result in a satisfactory position. If a table is not available the arm can be supported at heart level by the examiner.

9.4 Carotid artery assessment

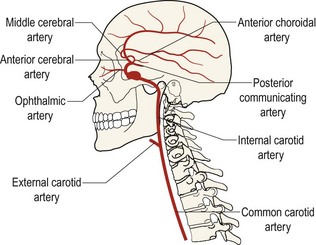

Carotid artery (Figure 9.3) occlusive disease may result in stroke, neurological disability or loss of life.5 Ocular risk factors for haemodynamically significant carotid artery stenosis include transient loss of vision (amaurosis fugax), retinal emboli (Hollenhorst plaques), retinal vascular occlusions, peripheral retinal haemorrhages with dilated and tortuous veins (hypoperfusion retinopathy), microrubeosis iridis, ocular ischaemic syndrome, anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, normal tension glaucoma and asymmetric diabetic retinopathy.5,6 Symptomatic patients are more likely than non-symptomatic patients to have carotid artery stenosis and the most common symptom is amaurosis fugax. Amaurosis fugax is a sudden onset, painless loss of vision in one eye that is described as a curtain coming down over the vision. The vision loss generally lasts longer than one minute.2 In addition, systemic risk factors are additive to the risk of carotid artery disease. These include hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (including coronary artery bypass graft, peripheral vascular disease, a history of transient ischaemic attacks or cerebrovascular accidents,) carotid bruit and smoking.5

Since ocular risk factors alone can be poor or unreliable predictors of carotid artery occlusive disease (studies show a range of 0 to 100%), the additional information gained by the detection of a carotid bruit can be helpful in referring the patient with ocular signs to have carotid artery studies performed.2,6

9.4.1 Comparison of tests

Auscultation for a systolic bruit is an easy rapid technique to gain information that aids the diagnosis of significant carotid stenosis (abnormal narrowing). A bruit is the sound of turbulence in blood flow when the normal laminar flow is disrupted by the stenosis. If a bruit is audible 77% of patients have been shown to have significant stenosis on angiography.6 However, only about 57% of patients with significant stenosis (over 50%) will have an audible bruit.6 Combining a history of amaurosis fugax and ocular signs such as venous stasis retinopathy or other signs of ocular ischaemia with the presence of a bruit increases diagnostic accuracy significantly. More sensitive testing for carotid stenosis includes duplex ultrasound scanning of the carotid arteries and carotid angiography, which are arranged through a referral to a family physician or internist.

9.4.2 Procedure for carotid auscultation

1. Explain the test to the patient: ‘I am now going to use a stethoscope on your neck to check your blood circulation.’

2. For the right carotid assessment, stand to the right of the patient and ask the patient to look to their left. For the left carotid assessment, stand to the left of the patient and ask the patient to look to their right. Adjust the headrest on the examination chair so that the patient’s head is resting backwards with the chin slightly elevated.

3. Adjust the stethoscope so that the bell side of the chestpiece is clicked into position to transmit sounds through the stethoscope.

4. Insert the earpieces of the stethoscope into your ears so that they angle forward towards your face (Figure 9.4).

5. Place the bell over the common carotid artery approximately 2.5 cm above the clavicle bone using gentle pressure.

6. Have the patient hold their breath in mid expiration to prevent the breath sounds from distracting from your evaluation and listen for bruits for a few seconds. A bruit is a ‘whooshing’ sound heard superimposed on the sound of the pulse. Have the patient resume breathing.

7. Reposition the stethoscope two or three times farther upwards on neck to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery and then the internal carotid artery. Listen for bruits.

9.4.3 Recording

| Carotid pulse: R 3+ | L3+ |

| Carotid bruit: R absent | L absent |

| Carotid pulse: R 1+ | L2+ |

| Carotid bruit: R soft, systolic bruit | L absent |

9.4.5 Interpretation

Picket et al. conducted a meta-analysis of the relationship between the presence of a carotid bruit and the subsequent occurrence of transient ischemic attacks (TIA), stroke and death from stroke.28 The rate ratio for TIA in patients with a bruit was 4.0, for stroke was 2.49 and for death from stroke was 2.71. In another meta-analysis Picket et al. found that the odds ratio in patients with a bruit for having a myocardial infarction was 2.15 and for cardiovascular death was 2.27.29 Therefore, referral should be made for an appropriate medical assessment in the presence of a carotid bruit. Note that the absence of a carotid bruit does not however rule out carotid stenosis as the artery could be nearly entirely occluded resulting in the absence of turbulent flow sounds. An evaluation of symptoms, ocular and other systemic risk factors and current and previous medical care for carotid disease should be considered when deciding on referral for further assessment.

9.4.6 Most common errors

1. Inter-observer variability is high with this procedure so practice is required to obtain reliable results.

2. Interpreting as abnormal a bruit found in children or young adults. These are a result of the vessel elasticity in this age group and are benign.

3. Producing an iatrogenic bruit by placing too much pressure on the artery. Moving the bell over the skin, moving your fingers on the chestpiece or breathing on the tubing can also produce confusing sounds.

References

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160.

2. McCullough, H, Reinert, C, Hynan, L, et al. Ocular findings as predictors of carotid artery occlusive disease: Is carotid imaging justified? J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:279–286.

3. Ehlers, J, Shah, C. The Wills Eye Manual. Chapter 5 Conjunctiva/Sclera/Iris/External Disease, 5th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

4. Blaustein, B. Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Disease: Chapter 3 Cardiovascular Disease. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.

5. Lyons-Watt, V, Anderson, S, Townsend, J, DeLand, P. Ocular and systemic findings and their correlation with hemodynamically significant carotid artery stenosis: a retrospective study. Optom Vision Sci. 2002;79:353–362.

6. Lawrence, PF, Oderich, GS. Ophthalmic finding as predictors of carotid artery disease. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2002;36:415–424.

7. Gardner, M. Basic Anatomy of the Head and Neck. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1992.

8. Uchio, E, Takeuchi, S, Itoh, N, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of acute follicular conjunctivitis with special reference to that caused by herpes simplex virus type 1. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:968–972.

9. Aoki, K, Kaneko, H, Kitaichi, N, et al. Clinical features of adenoviral conjunctivitis at the early stage of infection. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55:11–15.

10. Hurcomb, P, Wolffsohn, J, Napper, G. Ocular signs of systemic hypertension: A review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2001;21:430–440.

11. Daskalopoulou, S, Khan, NA, Quinn, RR, et al. The 2012 Canadian Hypertension education program recommendations for the management of hypertension: blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk and therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:270–287.

12. NICE clinical guideline CG 217. Hypertension: Clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. www.guidance.nice.org.uk/CG217, 2011.

13. Meetz, R, Harris, T. The optometrist’s role in the management of hypertensive crises. Optometry. 2011;82:108–116.

14. Kearney, PM, Whelton, M, Reynolds, K, et al. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004;22:11–19.

15. Chobanian, AV, Bakris, GL, Black, HR, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252.

16. DellaCroce, J, Vitale, A. Hypertension and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19:493–498.

17. Wong, T, Mitchell, P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2310–2317.

18. Wolffsohn, JS, Napper, GA, Ho, SM, et al. Improving the description of the retinal vasculature and patient history taking for monitoring systemic hypertension. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2001;21:441–449.

19. Neto, J, Palacio, G, Santos, A, et al. Direct ophthalmoscopy versus detection of hypertensive retinopathy: a comparative study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;95:215–222.

20. Barnard, N, Allen, R, Field, A. Referrals for vascular hypertension in a group of 45–64-year-old patients. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1991;11:201–205.

21. Beevers, G, Lip, G, O’Brien, E. ABC of hypertension: Blood pressure measurement. Part I-Sphygmomanometry: factors common to all techniques. Br Med J. 2001;322:981–985.

22. World Health Organization. Affordable Technology: Blood pressure measuring devices for low resource settings. WHO library; 2005.

23. Skirton, H, Chamberlain, W, Lawson, C, et al. A systematic review of variability and reliability of manual and automated blood pressure readings. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:602–614.

24. Myers, M, Godwin, M. Automated office blood pressure. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:341–346.

25. Wan, Y, Heneghan, C, McManus, R, et al. Determining which automatic digital blood pressure device performs adequately: a systematic review. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:431–438.

26. Hodgkinson, J, Mant, J, Martin, U, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. Br Med J. 2011;342:d3621.

27. Lou, BP, Brown, GC. Update on the ocular manifestations of systemic arterial hypertension. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:203–210.

28. Picket, C, Jackson, J, Hemann, B, Atwood, J. Carotid bruits and cerebrovascular disease risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2010;41:2295–2302.

29. Picket, C, Jackson, J, Hemann, B, Atwood, J. Carotid bruits as a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:1587–1594.