Chapter 5 Physical Examination

What Is Important in the Physical Examination?

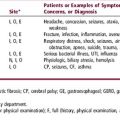

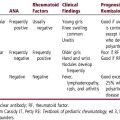

The content of the physical examination depends on the patient’s age, developmental stage, and the reason for the evaluation. Table 5-1 lists age-specific physical examination components. In general, a health supervision visit, a hospital admission, or the assessment of a complex complaint demands a comprehensive examination. Assessment of the daily progress of a hospitalized patient or the evaluation of a specific problem for a patient in a clinic will typically require an examination focused on the systems involved. Use of resources such as those listed in the reference section will greatly expand your knowledge of physical findings in infants, children, and adolescents.

Table 5-1 Age and Developmental Stage–Related Focus for Physical Examination

| Age | Focus |

|---|---|

| Newborn (see Chapter 14) | Assessment of gestational age |

| Determination of appropriateness of size for gestational age | |

| Identification of birth injuries and congenital anomalies | |

| Diagnosis of acute neonatal illnesses | |

| Infant | Assessment and monitoring of growth, development, and temperament |

| Late manifestations of congenital anomalies or delayed sequelae of neonatal problems | |

| Tympanic membranes, emergence of teeth | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| For an ill infant: Observe skin color, perfusion, hydration, and oxygenation; assess respiratory effort, level of consciousness, social interaction, and quality of the cry | |

| Toddler | Assessment and monitoring of growth and of developmentalprogress |

| Observation of behavior and child-parent interactions | |

| Gait, dentition, vision, hearing (middle ear status), and bloodpressure (after age 3) | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| School-age | Assessment and monitoring of growth, including body mass index (BMI) |

| Signs of puberty: girls after age 7 or 8 and boys after age 9 | |

| Dentition, development, behavior, blood pressure, vision, hearing, and scoliosis | |

| Focus on patient concerns | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| Adolescent (see Chapter 15) | Assessment and monitoring of growth, including BMI, and puberty |

| Breast self-examination for girls and testicular self-examination for boys | |

| Blood pressure, acne, dentition, signs of abuse | |

| Acute or chronic illness concerns | |

| Mental status observations |

VITAL SIGNS, APPEARANCE, AND BEHAVIOR

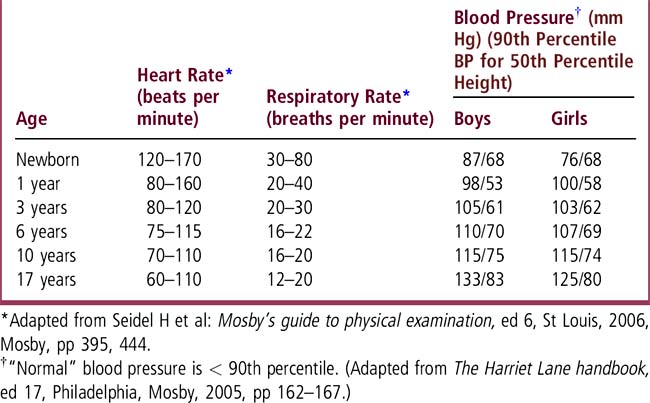

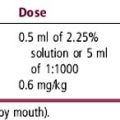

Review vital signs and compare them with age-specific reference data (Table 5-2). “Normal” vital signs are age (and often sex and size) specific. “Normal” blood pressure (BP) is below the 90th percentile for age, sex, and height. Hypertension is defined as persistent BP readings above the 95th percentile for age, sex, and height. BP is discussed in Chapter 46. Use growth charts to assess height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and head circumference. Pay attention to symmetry of growth, morphologic features, development, behavior, and the patient’s interaction with parents and the examiner. Observe mental status in older children and adolescents. When evaluating an acute illness, look for disease-specific signs plus evidence of shock or toxicity, such as skin color, respiratory effort, hydration status (capillary refill), mental status, cry, and interactions. Chronic illness may result in growth abnormalities, system/organ-specific dysfunction, or other characteristic findings. A patient’s appearance and physical findings may reflect a pattern of malformation that is characteristic of a syndrome or other identifiable cause of structural defects (see Chapter 62).

HEAD, EYES, EARS, NOSE, AND THROAT (HEENT)

HEAD

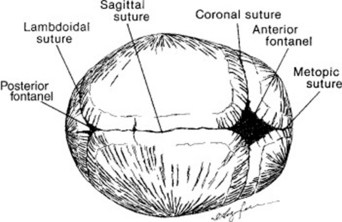

Measure head size and plot the data on the growth chart. Head circumference increases steadily from an average of 34 cm at birth to 48 cm (girls) and 49 cm (boys) by age 2; it then increases more slowly until the mean adult value of 55 cm (female) and 56 cm (male) is reached. Look at head shape and symmetry, facial features, and hair whorls. Identify the sutures and fontanels in an infant (Figure 5-1 and Chapter 14); these are usually not palpable after 15 to 18 months, occasionally earlier. The anterior fontanel is diamond shaped and at birth is approximately 2 × 2 cm (range 1 × 1 to 3 × 4 cm). The posterior fontanel is usually not palpable, even at birth, but when open it is the size of a small fingertip (< 1 × 1 cm). The superior surface of the anterior fontanel is generally level with the surface of the skull. Marked ridging or bony prominence of sutures in young infants may reflect premature fusion (synostosis). Widely separated sutures may reflect increased intracranial pressure and may be accompanied by a bulging and enlarged anterior fontanel. To determine whether the fontanel is bulging, move the infant to a sitting position, inspect the fontanel, then run your fingers across the fontanel surface. If the fontanel protrudes convexly beyond the skull’s surface, it is bulging. Dehydrated infants often display a sunken fontanel, concave with respect to the skull surface.

EYES

Identify the red reflex: Absence of the red reflex or presence of a white reflex always demands further evaluation. Assess extraocular motions and the corneal light reflection (see Eye Simulator, http://cim.ucdavis.edu/EyeRelease). Asymmetrical corneal light reflection is seen with strabismus. Young infants, especially Asian infants, commonly demonstrate pseudostrabismus, an artifact associated with prominent epicanthal folds (Figure 5-2). The corneal light reflection is symmetrical in pseudostrabismus.

EARS

Ask a parent to assist with the examination of the young child (seeFigure 30-1). Look at the external ears to assess structure, position, and symmetry. Examine the tympanic membranes using pneumatic otoscopy. Identify the tympanic membrane’s color, position, bony landmarks, light reflex, and movement to insufflation. Use a checklist as a guide (Table 30-1). Practice holding the otoscope, stabilizing the patient’s head, and squeezing the bulb while examining the ear of a cooperative individual (a classmate or friend). Use the largest otoscope tip available that will fit the external canal to ensure an optimal view of the tympanic membrane. Nondisposable otoscope tips are longer and wider than the disposable tips, provide a better view of the tympanic membrane (TM), and also make a better seal for pneumatic otoscopy. Remember to clean these tips after use. If cerumen obscures the tympanic membrane, it must be removed to allow an examination. If you do not feel comfortable using a cerumen scoop, ask for assistance.

NECK

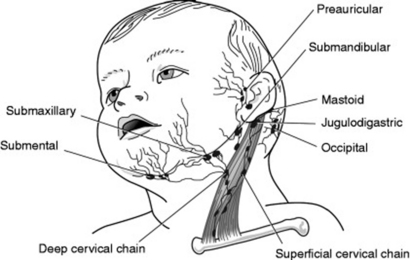

Cervical lymph nodes can be palpated in healthy children, but they are not large, immobile, tender, fluctuant, or inflamed. Figure 5-3 shows the anatomic areas drained by the cervical nodes. The thyroid gland should be small and smooth and have no nodules or tenderness. Examine the range of motion (flexion, extension, lateral bending, rotation) of the neck, and, when appropriate, test for nuchal rigidity.

CARDIOVASCULAR

Palpate pulses in the carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, and dorsalis pedis areas. Hydration status and peripheral perfusion is best tested with capillary refill, which should be < 2 seconds. Observe and palpate precordial activity. Auscultate the heart for rhythm, rate, quality of the heart sounds, and murmurs. Young children often have prominent “sinus arrhythmia,” a physiologic variation of heart rate associated with the respiratory cycle: rate increases with inspiration and decreases with expiration. You should be able to hear the physiologic splitting of the second heart sound at the second or third left intercostal space even in infants with a rapid heart rate (the splitting will be a “blurring” of the second heart sound during inspiration with return to a “crisp” sound during expiration). A venous hum is often heard when a young child is sitting and turns the head to one side; this is a continuous to-and-fro sound that disappears when supine or with head movement. Physiologic murmurs change with position, often being more prominent when supine and diminishing when sitting. Pathologic heart murmurs are loud, often occur in diastole, and do not change with position (discussed in Chapter 48).

GENITALIA

BOYS

Determine whether the penis has been circumcised. Check for phimosis in uncircumcised boys, but remember that the foreskin cannot be fully retracted until after ages 4 to 6 years in most boys. The urethral meatus should be located at the tip of the glans; if it is lower on the glans or on the shaft of the penis, hypospadias is present. Palpate the testes to ensure that both are descended into the scrotum and to identify an undescended testis (cryptorchidism), hernia, hydrocele, or testicular mass. Characterize genitalia according to sexual maturity (Tanner) stages (Chapter 15).

MUSCULOSKELETAL AND EXTREMITIES

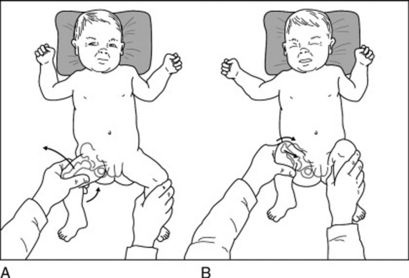

The musculoskeletal examination is important at all ages. Examine the newborn’s hips with Ortolani and Barlow maneuvers (Figure 5-4) to identify developmental dysplasia. The Ortolani maneuver identifies the dislocated hip, which will be felt to move anteriorly (reduce) into the acetabulum, with a palpable or audible “clunk.” The Barlow maneuver identifies the dislocatable hip, which will be felt to move posteriorly (dislocate) out of the acetabulum, with a palpable or audible clunk. Use the musculoskeletal evaluation of older children and adolescents to identify restricted or excessive joint mobility, joint effusions, signs of trauma, and gait abnormalities.(Figure 68-1shows age-related variations of the legs and feet: genu varus and valgus, flexible flat feet, metarsus varus, tibial torsion, and femoral anteversion. The “2-minute musculoskeletal examination” assesses strength, symmetry, flexibility, muscle bulk, and range of motion (Figure 68-2). Common pediatric orthopedic problems are discussed inChapter 68

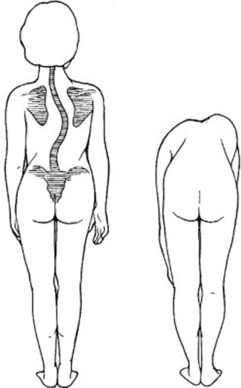

BACK

The scapulae and iliac crests should be symmetrical in appearance, prominence, and placement. Inspect and palpate the spine along its entire length to identify curves, hair tufts, pits, dimples, or masses. Dimples over the lower spine are common and do not need further investigation if the underlying skin is intact. If not, investigate to identify a sinus tract or underlying abnormality. A dimple in the coccygeal or gluteal cleft area is usually benign, whereas a sacral dimple may represent an occult spinal dysraphism (spina bifida occulta). Examine school-age children and adolescents for scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis. Figure 5-5 demonstrates the technique to identify scoliosis.

NEUROLOGIC

Observation is a key tool for the neurologic examination. Assess developmental milestones, symmetry, tone, strength, and reflexes. Primitive reflexes, including rooting, sucking, obligate grasp, Moro reflex, and tonic neck reflex, are found in healthy newborns and young infants. Persistence of primitive reflexes beyond 4 to 6 months should raise concern (Chapter 58). You should be able to demonstrate the findings that reflect the disappearance of primitive reflexes (e.g., the voluntary grasp of an infant older than 2 months indicates that the reflexive grasp of the newborn has disappeared).

SKIN

Observe and palpate the skin to assess color, perfusion, turgor, pigmented lesions, and rashes. Identify jaundice, petechiae, purpura, vesicles, and urticaria (Chapter 49). Examine the skin for common birthmarks and skin conditions unique to children (Chapter 57). Recognize bruises and other characteristic findings of child abuse (Chapter 24).

Jones KL. Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation, ed 6. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2006.

Paller AS, Mancini AJ. Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2006.

Robertson J, Shilkofski N. The Harriet Lane handbook, ed 17. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2005.

Seidel HM, et al. Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby, 2006.

Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 4. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2002.