Chapter 1 Physical Examination

The diagnosis of disorders of the musculoskeletal system begins with compiling a complete history and performing a physical examination. The history is of special significance because physical findings are often minimal. Its importance cannot be overemphasized. Most musculoskeletal conditions should be able to be diagnosed by history and physical examination alone. Referral for elaborate laboratory or radiographic testing is usually unnecessary in the analysis of most orthopedic conditions, at least in the early stages.

History

BIRTH HISTORY

The physical and mental development of the child is then determined, and any deviation from normal progress is noted (Table 1-1).

| Age (mo) | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Holds up chin |

| 6–8 | Sits alone |

| 8–10 | Stands with support |

| 10–12 | Walks with support |

| 14 | Walks without support |

| 24 | Ascends stairs one foot at a time |

* Note: There is frequently a wide variation in physical development, but if a child cannot walk unsupported by 18 months of age, a neuromuscular disorder should be suspected. A wide-based gait is often the first noticeable abnormality when neuromuscular disease is present in the child. In addition, the child should not have hand preference before 18 months of age.

For greatest accuracy, the ages of all children should be listed by years plus months.

PAST HISTORY

The general health of the patient is recorded, as well as any recent weight loss or gain. The patient’s exact occupation should be determined and any relevant military history noted, especially if a disability rating resulted from time spent in the service. The disorder that prompted the rating is noted, and impairment ratings from other sources are also recorded. All chronic renal, metabolic, pulmonary, and previous orthopedic disorders should be assessed in view of the initial complaint. Any drug or alcohol use is recorded. The smoking history is especially important, because tobacco use may adversely affect multiple musculoskeletal conditions, including osteoporosis, fracture healing, and low back pain.

PRESENT ILLNESS

When deformity is the initial complaint, the following information should be obtained:

The assessment of crepitation is often difficult. It is frequently an inconsistent finding. Some noise is considered normal in certain joints, especially in the absence of other symptoms, such as pain. In other cases, synovial hypertrophy (joint or tendon sheath) or a significantly irregular joint surface may cause crepitus (and pain) with certain movements. By itself, crepitus is not considered pathologic, but its exact etiology may be difficult to explain.

Examination

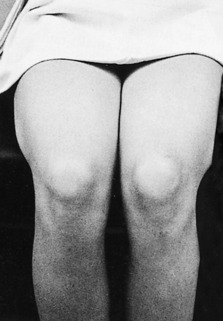

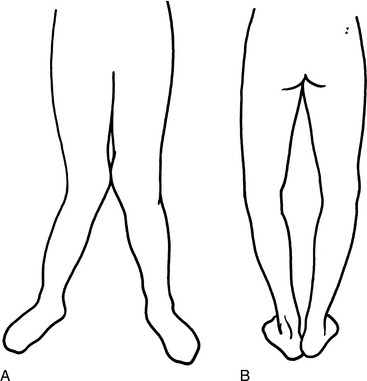

Valuable information can frequently be gained by merely observing the gait, general posture, and stance of many patients. This is especially helpful in the child who may otherwise be difficult to examine. The patient should be viewed moving about, such as getting in and out of the chair. The height and weight of the patient are recorded, and all examinations are performed with the affected area completely exposed (Fig. 1-1). The patient should always be viewed in profile as well as from the front and back. In addition, certain areas may lend themselves to a different view. For example, subtle swelling of the metacarpophalangeal joints and dorsal intermetacarpal soft tissue can be visualized clearly by viewing and comparing the patient’s clenched fists pointed toward the examiner. Posterior ankle and heel cord swelling can also be assessed by asking the patient to kneel on a chair and viewing the swollen areas from the back of the patient.

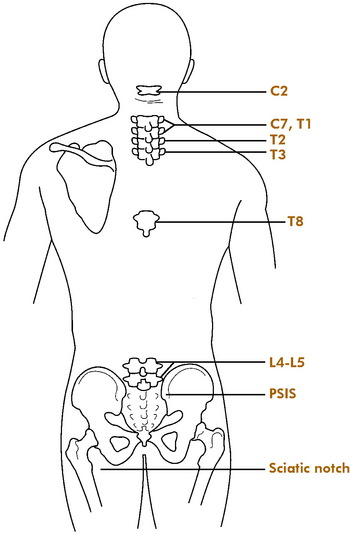

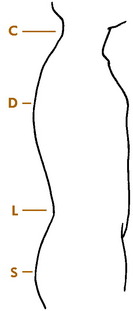

The affected area is then inspected, and any swelling, discoloration, or areas of tenderness are noted. Palpation should be gentle but persistent. Sometimes in the child, it is easier to start at a distance from the injured or painful site and slowly work toward the area in question. Every attempt should be made to describe the affected areas according to their exact anatomic location. Movements or maneuvers that exacerbate the pain are recorded, as well as nonorganic behavior or pain magnification during the examination. Any muscle atrophy is noted and compared with measurements of the opposite extremity. Muscle power is tested in a similar manner. Alterations in skin temperature or perspiration are also noted, especially in the lower extremity. Any signs of circulatory disturbance (edema, dependent rubor, or distal hair loss) should also be recorded. References to known anatomic landmarks are used whenever possible (Fig 1-2).

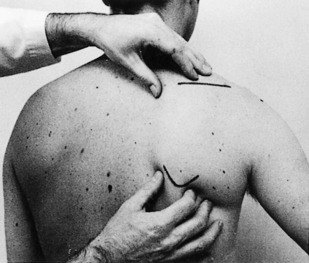

Active and passive ranges of joint motion are carefully measured, and the patient is observed for any crepitus or resistance to movement. Allowances for patient age and size should be considered when calculating whether range of motion would be considered “normal.” During the examination, adjacent joints may need to be stabilized to properly measure the affected joint (Fig. 1-3). Always examine the unaffected opposite extremity for comparison.