Photodermatology

Photodermatoses – idiopathic

Polymorphic light eruption

Clinical presentation

This is the commonest photodermatosis, and women are affected twice as frequently as men. Pruritic urticated papules, plaques and vesicles develop on light-exposed skin usually about 24 h after sun or artificial ultraviolet (UV) exposure (Fig. 1). It starts in the spring and may persist throughout the summer. The degree of severity is variable.

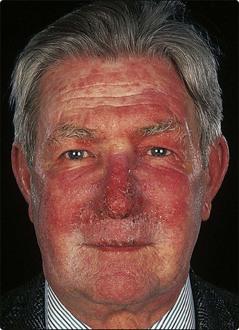

Chronic actinic dermatitis (actinic reticuloid)

Clinical presentation

There is often a long history of a chronic dermatitis that evolves into a photodermatitis, or a photoallergic contact dermatitis may have been present from the outset. Lichenified plaques of chronic dermatitis form on light-exposed sites and beyond, and are worse in the summer, although the eruption tends to become perennial (Fig. 2). The patients are sensitive to the UVA and UVB wavelengths and often to visible light as well. They may also have a contact or photocontact sensitivity to plant sesquiterpene lactones (airborne allergens) or to cosmetic ingredients, although the contribution of this to the overall picture is unclear.

Solar urticaria and actinic prurigo

Solar urticaria and actinic prurigo are rare conditions. In solar urticaria, wheals appear within minutes of exposure to sunlight. Differentiation is required from erythropoietic protoporphyria (p. 47), especially in childhood. Actinic prurigo starts in childhood and is characterized by papules and excoriations, mainly on sun-exposed sites. Actinic prurigo is strongly associated with HLA-DRB1*0401 or 07.

Photodermatoses – other causes

Genetic disorders

Certain rare genetic disorders show photosensitivity. They may have chromosome instability (e.g. Bloom syndrome) or defective DNA repair (e.g. xeroderma pigmentosum, p. 91).

Metabolic disorders

Porphyrias

Porphyrins are important in the formation of haemoglobin, myoglobin and cytochromes. The porphyrias are rare, mostly inherited, metabolic disorders in which deficiencies of enzymes in the porphyrin biosynthetic pathway lead to accumulations of intermediate metabolites (p. 84). The metabolites are detectable in the urine, faeces and blood, are toxic to the nervous system and cause photosensitivity in the skin.

The main cutaneous porphyrias are the following:

Erythropoietic protoporphyria. Autosomal dominant and starting in childhood, this is a painful red blistering eruption. Pitted linear scars are left on the nose and hands. New therapies designed to induce photoprotection through tanning via synthetic analogues of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) are under trial.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria. Autosomal dominant and starting in childhood, this is a painful red blistering eruption. Pitted linear scars are left on the nose and hands. New therapies designed to induce photoprotection through tanning via synthetic analogues of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) are under trial.

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This is the commonest porphyria, often associated with liver disease and frequently alcohol related. Sun-induced subepidermal blisters on the face and hands (Fig. 3) leave fragile, scarred and hairy skin. Alcohol and aggravating drugs (e.g. oestrogens) are avoided. Venesection or low-dose chloroquine therapy may be used.

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This is the commonest porphyria, often associated with liver disease and frequently alcohol related. Sun-induced subepidermal blisters on the face and hands (Fig. 3) leave fragile, scarred and hairy skin. Alcohol and aggravating drugs (e.g. oestrogens) are avoided. Venesection or low-dose chloroquine therapy may be used.

Variegate porphyria. Autosomal dominant and common in South Africa, the skin signs are like porphyria cutanea tarda. However, acute attacks with abdominal pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms resemble acute intermittent porphyria, which has no skin features.

Variegate porphyria. Autosomal dominant and common in South Africa, the skin signs are like porphyria cutanea tarda. However, acute attacks with abdominal pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms resemble acute intermittent porphyria, which has no skin features.

Due to drugs or chemicals

Drug induced

Several drugs may produce an eruption in light-exposed areas by either toxic (dose-dependent) or allergic mechanisms. The morphology may be eczematous, blistering (e.g. griseofulvin, p. 17), pigmented (e.g. amiodarone, p. 86) or an exaggerated sunburn reaction. Rarely, photo-onycholysis can occur (e.g. with tetracycline). Common photosensitizing drugs are shown in Box 1.

Topically applied chemicals

The commonest topical photosensitizers (i.e. allergens) are sunscreen agents (e.g. benzophenones), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), coal tar derivatives and fragrances. Topical phototoxicity (with an irritant mechanism) is usually due to plant-derived psoralens, as found, for example, in carrot, celery, fennel, parsnip, common rue and giant hogweed. Phytophotodermatitis describes a photocontact dermatitis that results from the local photosensitization of the skin through contact with psoralens from a plant (Fig. 4). In Berloque dermatitis, streaky pigmentation, often on the sides of the neck, results from the application of perfumes containing psoralens, usually oil of Bergamot (p. 107).

Dermatoses improved or worsened by sunlight

UV improves certain conditions (Table 1) and is used as a treatment as natural sunlight, UVB or PUVA. However, benefit is not observed in every case, and UV can, for example, make a patient’s psoriasis or atopic eczema worse. The sun may even precipitate psoriasis. The sun can aggravate several other conditions, listed in Table 1.

| Improved | Worsened or provoked |

|---|---|

| Acne | Darier’s disease |

| Atopic eczema | Herpes simplex |

| Mycosis fungoides | Lupus erythematosus |

| Pityriasis rosea | Porphyrias |

| Psoriasis | Rosacea |

| Uraemic pruritus | Vitiligo |

Photodermatology

In normal skin, sunlight can cause tanning, sunburn, photoageing (p. 106) and photocarcinogenesis (p. 100 – squamous cell carcinoma, new spread).

In normal skin, sunlight can cause tanning, sunburn, photoageing (p. 106) and photocarcinogenesis (p. 100 – squamous cell carcinoma, new spread).

The important idiopathic photodermatoses are polymorphic light eruption, chronic actinic dermatitis (actinic reticuloid) and solar urticaria.

The important idiopathic photodermatoses are polymorphic light eruption, chronic actinic dermatitis (actinic reticuloid) and solar urticaria.

Dermatoses worsened by sunlight include Darier’s disease, herpes simplex, lupus erythematosus, cutaneous porphyrias, rosacea and vitiligo.

Dermatoses worsened by sunlight include Darier’s disease, herpes simplex, lupus erythematosus, cutaneous porphyrias, rosacea and vitiligo.

Dermatoses improved by sunlight include acne, atopic eczema, mycosis fungoides, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis and the pruritus of renal failure.

Dermatoses improved by sunlight include acne, atopic eczema, mycosis fungoides, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis and the pruritus of renal failure.

Drugs that are not infrequent causes of photosensitivity include tetracyclines, phenothiazines, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), furosemide and thiazides.

Drugs that are not infrequent causes of photosensitivity include tetracyclines, phenothiazines, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), furosemide and thiazides.