Chapter 113 Phosphatidylserine

Introduction

Introduction

Phosphatidylserine (PS) is a phospholipid nutrient that occurs naturally in all cells; it is an orthomolecule according to Linus Pauling’s definition.1 PS is most highly concentrated in brain cells, and as a dietary supplement its clinical benefits are most apparent in brain-related functions, including cognition, mood, and stress management.2–6

PS is fundamentally important for life. It is an essential building block for the cell membrane system that manages most life processes.6 Cell membranes are thin, continuous structures composed mainly of phospholipids (a lipid bilayer), into which are inserted myriad catalytic proteins. PS is an essential phospholipid for the membrane system, helping to create the physical–chemical milieu appropriate for optimal protein activity.2,7

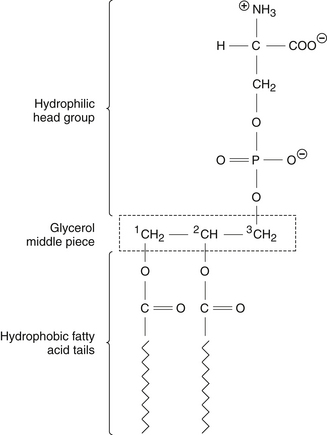

The PS molecule has a characteristic layout (Figure 113-1)—a head piece, a middle piece, and two tail pieces (“tails”).2,7 The head piece contains serine attached to a phosphoryl group, has a net negative charge, and is positioned on the membrane’s inner (cytoplasmic) surface.7 The middle piece is a 3-carbon glyceryl sequence. The two tail pieces are constructed from fatty acids, extend deep into the membrane, and help maintain the semi-fluid membrane interior that the proteins require for their catalytic activity.2

Biochemically, PS is not a single molecule but a family of molecules.2,8 The head and middle pieces are standard, but each of the two tail groups can be constructed from many different fatty acids. Thus, there are as many PS molecules as there are fatty acid permutations. Further, all cells carry enzymes (“acylases”) that can detach one fatty acid tail and substitute it with another, depending on the need for membrane fluidity.8 In the brain’s highly active gray matter, the PS molecules on average carry more of the highly fluidizing ω-3 fatty acids; in contrast, PS in the white matter has less ω-3 and more saturated and mono-unsaturated (ω-9) fatty acid tails.8

Physiologic Roles

Physiologic Roles

The presence of PS in cell membranes enables the brain’s electrical activity, the blood’s clotting properties, bone matrix formation, and the selective removal of dying cells from the tissues.2,7 All these processes are based in cell membrane structure and function. At the cell membrane level, activities specifically linked to PS include8–12:

• Energetics: Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production by the mitochondria relies on phosphatidylethanolamine in their membranes, generated exclusively from PS.8

• Membrane/cell stabilization: PS binds with structural proteins to stabilize the cell’s outer membrane and overall cell shape.9

• Signal transduction: The conversion of external signals to internal cell transformations, which often requires protein kinase C, a PS-dependent protein.10

• Secretion: The presence of PS enables membrane vesicles within the cell to fuse with the outer cell membrane and release their contents.11

• Apoptosis: A cell that is dying allows its PS to “flip” to the outer (external) face of the cell membrane. This serves as a “suicide” signal for immune cells to recycle that cell.12

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

The pharmacology of PS is consonant with its diverse actions in cell membranes.2,13,14 In animal studies, PS enhanced the activities of at least nine major transmitter systems (reviewed in Kidd2). In animal and human studies, PS enhanced stress management via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis,14 as well as the diurnal hormone secretory rhythms of the pituitary gland.15

Other animal findings indicated PS has an overall trophic (restorative) effect in the brain. Feeding PS to aging rats significantly slowed the usual age-related decline of forebrain cholinergic synapses16 and of nerve cells and their dendritic densities in the hippocampus.17,18 Also in aging rats, PS by mouth significantly slowed the age-associated decline of receptors for nerve growth factor, a protein factor that stimulates brain circuit maintenance and renewal.18

Consistent with its importance for mitochondrial function, PS supports brain energetics. A single-photon emission computed tomographic imaging study of dementia patients found that orally administered PS improved energy production and utilization throughout the brain.19

Clinical Applications

Clinical Applications

The primary clinical application of PS is to correct impaired mental functioning in the middle-aged and elderly. In multiple randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, PS consistently improved memory, learning, word recall, and other cognitive functions.2–5,20–28 In one such trial conducted with healthy subjects at the earliest stage of measurable cognitive decline (age-associated memory impairment), PS seemingly reversed the decline in the subgroup that was afflicted worst at the outset.3

Against full-blown Alzheimer’s disease, the benefits of PS typically included improvement in activities of daily living, verbal expression, and sociability,2,5,20,21,23 as well as mild improvements in memory and concentration.2,4,5 In the largest controlled trial,5 425 elderly Alzheimer patients (aged 65 to 93 years) received either PS (300 mg/day) or a placebo for 6 months.5 The PS group showed improvements in memory, learning, withdrawal, apathy, and “adaptability to the environment” that were highly statistically significant (P <0.01) compared with the placebo group.

In May 2003, PS acquired elite status as a brain nutrient. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted two “qualified health claims” that allowed that PS may (1) reduce the risk of dementia in the elderly, and (2) reduce the risk of cognitive dysfunction in the elderly.29

PS also can improve mood and anxiety.2,30–32 In a small double-blind trial in women with major depression, PS (300 mg/day vs placebo for 30 days) significantly improved the symptoms of depression and anxiety along with cognition, irritability, and sociability.30 PS (200 mg/day, 30 days) again significantly improved depression in another small controlled trial with elderly women.31 In a double-blind trial in elderly men with cognition problems, PS significantly lessened the risk of developing the “winter blues.”32 An early clinical study suggested PS could partially revitalize the aging HPA axis in aging humans.33

PS also improved the ability of young, healthy subjects to cope with stress, whether physical or psychological. PS alleviated students’ perceived stress from timed mental arithmetic testing (300 mg/day for 30 days).34 Another double-blind trial had healthy subjects making an unrehearsed job application speech and doing complex mental arithmetic.35 In this trial, subjects who received a phospholipid complex with 400 mg PS and 500 mg phosphatidic acid showed significantly less distress and significantly lowered stress hormone elevations of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol compared with placebo.

In the physical arena, PS improved golfers’ driving accuracy (at just 200 mg/day for 42 days)36 and other physical performances in cycling, running, and weight training.37 Physical and mental challenges often raise blood cortisol, and PS can blunt this cortisol response, albeit at relatively high doses (400 to 800 mg/day).35,37

The PS originally used in clinical studies came from cow brains (“bovine cortex PS,” “BC-PS”), but “mad cow disease” made this source untenable, and soy became the new source. Unlike BC-PS, initially all soy PS totally lacked ω-3 docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in its tails.38 However, this soy PS without DHA showed clinical benefits in a number of double-blind trials.6,31,32,34–36

Recently PS carrying DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (“PS ω-3”) has become available as a dietary supplement. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, consumption of a PS ω-3 providing PS 300 mg/day, ω-3 EPA 156 mg/day, and ω-3 DHA 95 mg/day for 3 months improved visual sustained attention.38 The PS ω-3 group experienced significantly more benefit than another group that received matching EPA and DHA allowances from fish oil triglycerides.

In a 2010 double-blind trial on non-demented elderly with memory complaints, another PS ω-3 preparation (PS 300 mg/day, EPA 20 mg/day, DHA 60 mg/day) significantly improved verbal immediate recall.39

Dosage

Dosage

The standard dosage recommendation for PS is 100 mg taken with meals one to three times daily.

Toxicology and Drug Interactions

Toxicology and Drug Interactions

After more than 16 years of use as a dietary supplement, PS has no evidence of drug interactions or adverse effects at dosages up to 800 mg/day.2,35,37

1. Pauling L. Orthomolecular psychiatry. Varying the concentrations of substances normally present in the human body may control mental disease. Science. 1968;160:265–271.

2. Kidd P.M. PS (PhosphatidylSerine), Nature’s Brain Booster, 2nd ed. St. George, UT: Total Health Communications; 2007.

3. Crook T.H., Tinklenberg J., Yesavage J., et al. Effects of phosphatidylserine in age-associated memory impairment. Neurology. 1991;41:644–649.

4. Crook T., Petrie W., Wells C. Effects of phosphatidylserine in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28:61–66.

5. Cennacchi T., Bertoldin T., Farina C., et al. Cognitive decline in the elderly: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study on efficacy of phosphatidylserine administration. Aging (Milano). 1993;5:123–133.

6. Starks M.A., Starks S.L., Kingsley M., et al. The effects of phosphatidylserine on endocrine response to moderate intensity exercise. J Intl Soc Sports Nutr. 2008;5:11–17.

7. Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

8. Vance J.E. Phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells: two metabolically related aminophospholipids. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1377–1387.

9. Manno S., Takakuwa Y., Mohandas N. Identification of a functional role for lipid asymmetry in biological membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1943–1948.

10. Manna D., Bhardwaj N., Vora M.S., et al. Differential roles of phosphatidylserine, PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in plasma membrane targeting of C2 domains. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26047–26058.

11. Borghese C.M., Gomez R.A., Ramirez O.A. Phosphatidylserine increases hippocampal synaptic efficacy. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:697–700.

12. Schutters K., Reutelingsperger C. Phosphatidylserine targeting for diagnosis and treatment of human diseases. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1072–1082.

13. Salem N., Niebylski C.D. The nervous system has an absolute molecular species requirement for proper function. Mol Membr Biol. 1995;12:131–134.

14. Samson J.C. The biological basis of phosphatidylserine pharmacology. Clin Trials J. 1987;24:1–8.

15. Masturzo P., Murialdo G., de Palma D., et al. TSH circadian secretions in aged men and effect of phosphatidylserine treatment. Chronobiologia. 1990;17:267–274.

16. Nunzi M.G., Milan F., Guidolin D., et al. Therapeutic properties of phosphatidylserine in the aging brain. In: Hanin I., Pepeu G. Phospholipids: Biochemical, Pharmaceutical, and Analytical Considerations. New York: Plenum Press, 1990.

17. Nunzi M.G., Milan F., Guidolin D. Dendritic spine loss in hippocampus of aged rats. Effect of brain phosphatidylserine administration. Neurobiol Aging. 1987;8:501–510.

18. Nunzi M.G., Guidolin D., Petrelli L., et al. Behavioral and morpho-functional correlates of brain aging: a preclinical study with phosphatidylserine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;318:393–398.

19. Klinkhammer P., Szelies B., Heiss W.D. Effect of phosphatidylserine on cerebral glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia. 1990;1:197–201.

20. Delwaide P.J., Gyselynck-Mambourg A.M., Hurlet A. Double-blind randomized controlled study of phosphatidylserine in demented patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:136–140.

21. Amaducci L. Phosphatidylserine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: results of a multicenter study. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:130–134.

22. Fuenfgeld E.W. Double-blind study with phosphatidylserine (PS) in parkinsonian patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type (SDAT). Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;317:1235–1246.

23. Hershkowitz M., Fisher M., Bobrov D., et al. Long-term treatment of dementia Alzheimer type with phosphatidylserine: effect on cognitive functioning and performance in daily life. In: Bazan N.G., Horrocks L.A., Toffano G. Phospholipids in the Nervous System: Biochemical and Molecular Pathology. Padova: Liviana Press; 1989:279–288.

24. Engel R.R., Satzger W., Gunther W., et al. Double-blind cross-over study of phosphatidylserine vs. placebo in patients with early dementia of the Alzheimer type. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1992;2:149–155.

25. Palmieri G., Palmieri R., Inzoli M.R., et al. Double-blind controlled trial of phosphatidylserine in patients with senile mental deterioration. Clin Trials J. 1987;24:73–83.

26. Nerozzi D., Aceti F., Melia E., et al. Phosphatidylserine and memory disorders in the aged. Clin Ter. 1987;120:399–404. [Italian]

27. Ransmayr G., Plörer S., Gerstenbrand F. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of phosphatidylserine in elderly patients with arteriosclerotic encephalopathy. Clin Trials J. 1987;24:62–72.

28. Villardita C., Grioli S., Salmeri G., et al. Multicentre clinical trial of brain phosphatidylserine in elderly patients with intellectual deterioration. Clin Trials J. 1987;24:84–93.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration/Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition. Phosphatidylserine and cognitive dysfunction and dementia (qualified health claim: final decision letter). May 2003

30. Maggioni M., Picotti G.B., Bondiolotti G.P., et al. Effects of phosphatidylserine therapy in geriatric patients with depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:265–270.

31. Brambilla F., Maggioni M., Panerai A.E., et al. Beta-endorphin concentration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of elderly depressed patients-effects of phosphatidylserine therapy. Neuropsychobiol. 1996;34:18–21.

32. Gindin J., Novikov M., Kedar D., et al. The effect of plant phosphatidylserine on age-associated memory impairment and mood in the functioning elderly. Rehovot, Israel: Geriatric Institute for Education and Research and Department of Geriatrics, Kaplan Hospital; 1995.

33. Nerozzi D., Magnani A., Sforza V., et al. Early cortisol escape phenomenon reversed by phosphatidylserine (Bros) in elderly normal subjects. Clin Trials J. 1989;26:33–38.

34. Benton D., Donohue R.T., Sillance B. The influence of phosphatidylserine supplementation on mood and heart rate when faced with an acute stressor. Nutr Neurosci. 2001;4:169–178.

35. Hellhammer J., Fries E., Buss C., et al. Effects of soy lecithin phosphatidic acid and phosphatidylserine complex (PAS) on the endocrine and psychological responses to mental stress. Stress. 2004;7:119–126.

36. Jaeger R., Purpura M., Geiss K.-R., et al. The effect of phosphatidylserine on golf performance. J Intl Soc Sports Nutr. 2007;4:23–28.

37. Jaeger R., Purpura M., Kingsley M. Phospholipids and sports performance. J Intl Soc Sports Nutr. 2007;4:5–13.

38. Vaisman N., Kaysar N., Zaruk-Adasha Y., et al. Correlation between changes in blood fatty acid composition and visual sustained attention performance in children with inattention: effect of dietary n-3 fatty acids containing phospholipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1170–1180.

39. Vakhapova V., Cohen T., Richter Y., et al. Phosphatidylserine containing omega-3 fatty acids may improve memory abilities in non-demented elderly with memory complaints: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:467–474.