Phosphate and magnesium

Phosphate

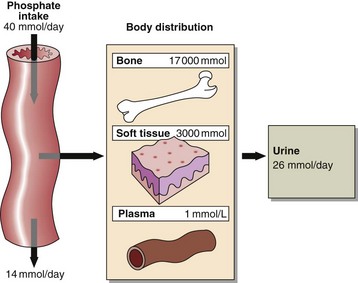

Phosphate is abundant in the body and is an important intracellular and extracellular anion. Much of the phosphate inside cells is covalently attached to lipids and proteins. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of enzymes are important mechanisms in the regulation of metabolic activity. Most of the body’s phosphate is in bone (Fig 37.1). Phosphate changes accompany calcium deposition or resorption of bone. Control of ECF phosphate concentration is achieved by the kidney, where tubular reabsorption is reduced by PTH. The phosphate that is not reabsorbed in the renal tubule acts as an important urinary buffer.

Hyperphosphataemia

Renal failure. Phosphate excretion is impaired. This is the commonest cause of hyperphosphataemia.

Renal failure. Phosphate excretion is impaired. This is the commonest cause of hyperphosphataemia.

Hypoparathyroidism. The effect of a low circulating PTH decreases phosphate excretion by the kidneys, and this contributes to a high serum concentration.

Hypoparathyroidism. The effect of a low circulating PTH decreases phosphate excretion by the kidneys, and this contributes to a high serum concentration.

Redistribution. Cell damage (lysis), e.g. haemolysis, tumour damage and rhabdomyolysis.

Redistribution. Cell damage (lysis), e.g. haemolysis, tumour damage and rhabdomyolysis.

Acidosis. There is impaired metabolism and therefore decreased intracellular utilization of phosphate.

Acidosis. There is impaired metabolism and therefore decreased intracellular utilization of phosphate.

Pseudohypoparathyroidism. There is tissue resistance to PTH.

Pseudohypoparathyroidism. There is tissue resistance to PTH.

Hypophosphataemia

Causes of a low serum phosphate include:

Hyperparathyroidism. The effect of a high PTH is to increase phosphate excretion by the kidneys and this contributes to a low serum concentration.

Hyperparathyroidism. The effect of a high PTH is to increase phosphate excretion by the kidneys and this contributes to a low serum concentration.

Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. The effect of insulin in causing the shift of glucose into cells may cause similar shifts of phosphate, which may result in hypophosphataemia.

Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. The effect of insulin in causing the shift of glucose into cells may cause similar shifts of phosphate, which may result in hypophosphataemia.

Alkalosis. Especially respiratory, due to movement of phosphate into cells.

Alkalosis. Especially respiratory, due to movement of phosphate into cells.

Refeeding syndrome. Hypophosphataemia is frequently encountered when malnourished patients are first fed, due to movement of phosphate into cells.

Refeeding syndrome. Hypophosphataemia is frequently encountered when malnourished patients are first fed, due to movement of phosphate into cells.

Oncogenic hypophosphataemia. This is a rare cause of severe hypophosphataemia seen in some tumours, and is due to renal phosphate wasting caused by overexpression of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) 23.

Oncogenic hypophosphataemia. This is a rare cause of severe hypophosphataemia seen in some tumours, and is due to renal phosphate wasting caused by overexpression of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) 23.

Hungry bone syndrome. See page 70.

Hungry bone syndrome. See page 70.

Ingestion of non-absorbable antacids, such as aluminium hydroxide. These prevent phosphate absorption.

Ingestion of non-absorbable antacids, such as aluminium hydroxide. These prevent phosphate absorption.

Congenital defects of tubular phosphate reabsorption. In these conditions phosphate is lost from the body.

Congenital defects of tubular phosphate reabsorption. In these conditions phosphate is lost from the body.

Magnesium homeostasis

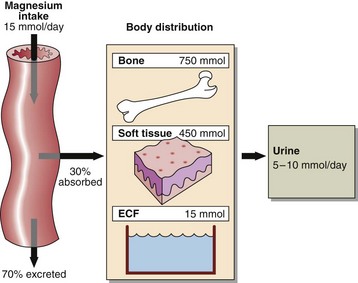

Since magnesium is an integral part of chlorophyll, green vegetables are an important dietary source, as are cereals and animal meats. An average dietary intake is around 15 mmol per day which generally meets the recommended dietary intake. Children and pregnant or lactating women have higher requirements. About 30% of the dietary magnesium is absorbed from the small intestine and widely distributed to all metabolically active tissue (Fig 37.2).

Magnesium deficiency

dietary insufficiency accompanied by intestinal malabsorption, severe vomiting, diarrhoea or other causes of intestinal loss

dietary insufficiency accompanied by intestinal malabsorption, severe vomiting, diarrhoea or other causes of intestinal loss

osmotic diuresis such as occurs in diabetes mellitus

osmotic diuresis such as occurs in diabetes mellitus

prolonged use of diuretic therapy especially when dietary intake has been marginal

prolonged use of diuretic therapy especially when dietary intake has been marginal

cytotoxic drug therapy such as cisplatin, which impairs renal tubular reabsorption of magnesium

cytotoxic drug therapy such as cisplatin, which impairs renal tubular reabsorption of magnesium