35 Pharyngitis

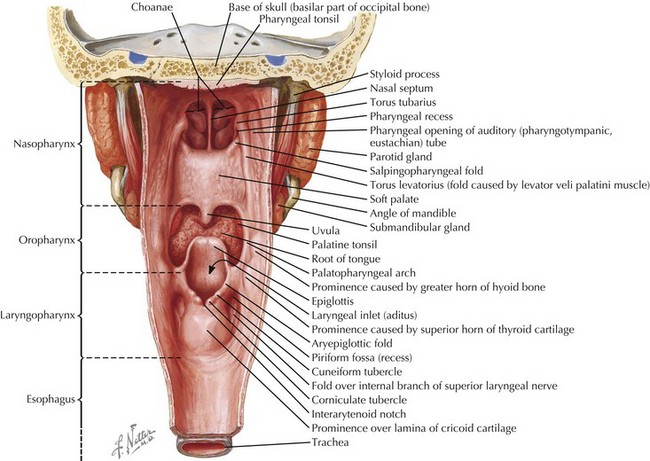

Pharyngitis is an inflammation of the mucous membranes and submucosal structures of the pharynx, including the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx (Figure 35-1). It accounts for approximately 7.3 million outpatient childhood doctor’s visits each year, and it remains one of the most common reasons for which children and adolescents seek medical attention. The cause of pharyngitis can vary widely depending on a person’s comorbidities, season of year, and exposure history, and the goals of diagnosis and management are to correctly treat the cases that require medical intervention and minimize the risk of long-term complications that may result from a primary pharyngitis. Yet despite the fever, sore throat, malaise, and associated symptoms that are often distressing to patients and their families, most cases of pharyngitis are benign and self-limited.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

There are numerous causes of pharyngitis, including infection, allergic rhinitis, environmental exposures, gastroesophageal reflux, and malignancy. The most common type of pharyngitis, however, is acute infectious pharyngitis, which is the focus of this chapter (Table 35-1). Viral infectious account for 40% to 60% of pediatric pharyngitis and usually present as part of a larger viral syndrome. Rhinovirus, adenovirus, and coronavirus, for example, present with sore throat along with fever, rhinorrhea, and other cold symptoms. Pharyngitis secondary to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), on the other hand, commonly presents in adolescents and young adults as a symptom of mononucleosis syndrome.

| Viral | Bacterial | Other Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinovirus | GABHS | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Adenovirus | Non-GABHS (group C and G) | Candida albicans |

| Coronavirus | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| RSV | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | |

| HSV | Arcanobacterium haemolyticum | |

| Parainfluenza | Francisella tularensis | |

| Influenza | Chlamydia pneumoniae | |

| Enterovirus | ||

| EBV | ||

| CMV | ||

| HIV |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GABHS, group A β-hemolytic streptococci; HSV, herpes simplex virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Alternatively, various bacteria may cause acute infectious pharyngitis. Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS), is the most common bacterial cause of pharyngitis. It accounts for 15% to 30% of pediatric pharyngitis and is an important pathogen to identify because treatment is essential in reducing the risk of postinfectious complications. Other common bacterial pathogens as well as a few fungal pathogens that can cause pharyngitis are listed in Table 35-1.

Clinical Presentation

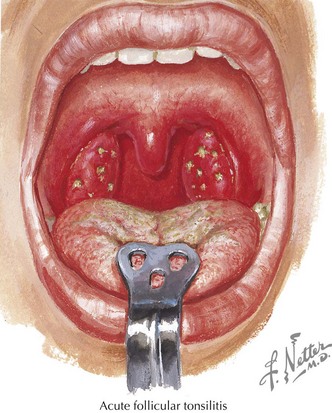

The presenting signs and symptoms surrounding pharyngitis can vary from one patient to another, yet some clinical findings are fairly typical of acute infectious pharyngitis. The most common findings in those with infectious pharyngitis include a history of fever; cervical lymphadenopathy; and oropharyngeal or tonsillar erythema, enlargement, or exudates (Figure 35-2). Although no definitive clinical presentations can correctly identify the cause of an individual’s pharyngitis, various signs and symptoms are more characteristic of one pathogen than another. These common presentations include:

Evaluation and Management

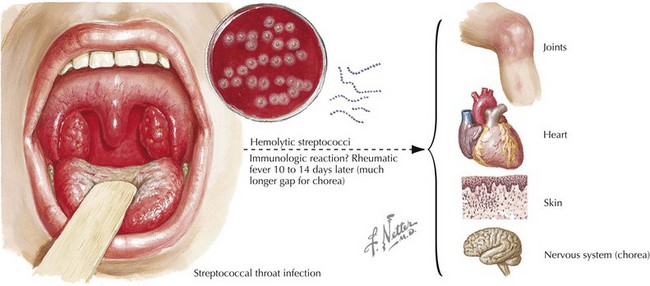

Although most cases of acute infectious pharyngitis resolve spontaneously within 3 to 7 days, the purpose of a diagnostic workup is to identify and treat pathogens that have potentially harmful sequelae (see Table 35-2 for common diagnostic testing). In particular, GABHS is the only common form of pharyngitis for which antimicrobial therapy is definitively indicated because it can prevent complications of the illness, most importantly, acute rheumatic fever (Figure 35-3). The additional benefits that come from antimicrobial treatment of GABHS are a reduction in the incidence of toxic shock syndrome, peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses, cervical lymphadenitis, and mastoiditis. The one sequela of GABHS that is not prevented by adequate treatment of strep pharyngitis is poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis.

| Pathogen | Diagnostic Test |

|---|---|

| GABHS | RADT, throat culture |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Thayer-Martin culture medium |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Fluorescent monoclonal antibody |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Loeffler agar, tellurite agar |

| Influenza | Rapid diagnostic testing, PCR, culture |

| EBV | Heterophile antibody, EBV serology, peripheral smear (atypical lymphocytosis) |

| CMV | CMV antibody titers |

| Herpes virus | HSV PCR |

| HIV | HIV RNA or HIV antibody |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GABHS, group A β-hemolytic streptococci; HSV, herpes simplex virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RADT, rapid antigen detection test.

Throat cultures can also be used to identify other bacterial causes of pharyngitis, but many laboratories will not look for additional organisms unless specifically asked to do so. If a child’s history and clinical presentation raise suspicion for an alternative source of infection, clinicians must remember that culture requirements may be different for the various pathogens (see Table 35-2). N. gonorrhoeae, for instance, requires Thayer-Martin culture medium for growth and Corynebacterium diphtheria grows on Loeffler agar or tellurite agar. Chlamydia pneumoniae, on the other hand, is most commonly detected by fluorescent monoclonal antibody testing.

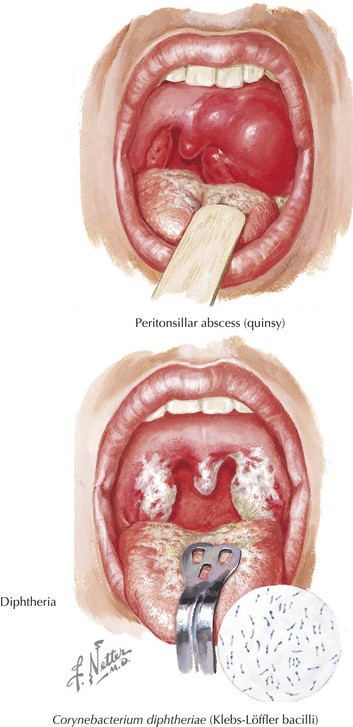

The treatment of patients with bacterial pharyngitis differs based on the causative pathogen (Table 35-3). Neisseria spp. are most commonly treated with a single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone along with azithromycin or doxycycline for empiric treatment of possible Chlamydia co-infection. Diphtheria, a disease more commonly found in unimmunized children, can lead to severe respiratory obstruction depending on the location of the pseudomembranes (Figure 35-4). Additionally, the toxin released by the bacteria can cause life-threatening neurotoxicity and cardiac toxicity. Therefore, the treatment for diphtheria includes both an antitoxin to counter the toxin in conjunction with penicillin or erythromycin to reduce the bacterial load. Other bacteria such as non-GABHS and Arcanobacterium haemolyticum rarely require antimicrobial treatment.

Table 35-3 Pharmacologic Management of Acute Infectious Pharyngitis

| Bacterial Pathogens | Treatment |

|---|---|

| GABHS | Penicillin–amoxicillin (second line: azithromycin, erythromycin, or clindamycin) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Ceftriaxone (with azithromycin or doxycycline for Chlamydia co-infection) |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Azithromycin (1 g single dose) or doxycycline (for 7 days) |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Penicillin or erythromycin and equine hyperimmune diphtheria antitoxin |

| Arcanobacterium haemolyticum* | Azithromycin–erythromycin or cephalosporins |

| Non-GABHS (group C and G)* | Penicillin (typically shorter duration than with GABHS treatment) |

| Viral Pathogens | Treatment |

| HSV | Acyclovir or valacyclovir |

| Influenza* | Oseltamivir–zanamivir or amantadine–rimantadine |

| HIV | Antiretrovirals |

| Other Infectious Pathogens | Treatment |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Azithromycin or doxycycline |

GABHS, group A β-hemolytic streptococci; HSV, herpes simplex virus.

* Treatment is not routinely indicated but may be used in children with specific comorbidities or clinical presentations.

With respect to viral pathogen identification, testing for the common viruses such as rhinovirus or coronavirus is not routinely indicated because identification of the pathogen will not change management of the patient. In immunocompromised patients or those with certain comorbid conditions, however, identification of adenovirus, influenza, or RSV can be useful because treatment may be indicated in these high-risk populations (see Table 35-3).

Altamimi S, Khalil A, Khalaiwi KA, et al. Short versus standard duration antibiotic therapy for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD004872.

Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;44(3):205-211.

Jaggi P, Shulman ST. Group A streptococcal infections. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27(3):99-105.

Merrill B, Kelsberg G, Jankowski A. What is the most effective diagnostic evaluation of streptococcal pharyngitis. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(9):734-739.

Pfoh E, Wessels MR, Goldman D, Lee GM. Burden and economic cost of group A Streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):229-234.

Tanz RR, Gerber MA, Kabat W, et al. Performance of a rapid antigen-detection test and throat culture in community pediatric offices: implications for management of pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):437-444.