CHAPTER 105 Pharmacologic Strategies in Back Pain and Radiculopathy

Back pain is a major health problem in the United States. About 70% to 85% of the population experiences back pain at some point in their lives with the annual prevalence ranging from 15% to 45%. Usually the clinical course is benign with 95% recovering within a few months of onset. It is most common in middle-aged adults with equal distribution in men and women. Back pain is the most frequent reason for activity limitation in young people younger than 45 years of age and the second leading cause for doctor visits and absenteeism from work. The lower back is the primary site of pain in 85% of the sufferers. It also has a major economic impact in the form of direct costs (costs incurred for physician services, medical devices, medications, hospital services, diagnostic testing, etc.) and indirect costs (cost incurred from absenteeism and decreased productivity). The cost of treating low back pain has been increasing, and total cost in the United States is estimated to exceed $100 to $200 billion per year. Two thirds of the cost is indirect, due to lost wages and reduced productivity. The rate of back surgery in the United States has increased dramatically, especially for spinal fusion.1–4

It is important to distinguish between nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain. Nociceptive pain results from tissue injury and subsequent activation of peripheral nociceptors, whereas neuropathic pain arises from the nerve injury or dysfunction. Radicular pain or pain in the distribution of the spinal nerve is a form of neuropathic pain. It is frequently referred to as sciatica when it involves the lower extremities. Radiculopathy is objective loss of sensory or motor function due to conduction block in the axons of a spinal nerve or its roots as a result of irritation of the outer layers of the nerve by compression or inflammatory mediators. It is important to avoid the indiscriminate use of adjunctive analgesics for nociceptive pain because they have a much stronger theoretical basis for use in neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is notoriously difficult to treat, and the paucity of well-designed, large, randomized, double-blind, and prospective placebo-controlled trials results in management decisions based on individual physician perspectives and experiences.5–9

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, is a p-aminophenol derivative with antipyretic and analgesic properties. It is frequently used as a first-line agent in acute low back pain and osteoarthritis due to its favorable gastrointestinal safety profile over aspirin and other anti-inflammatory drugs.10–11 The mechanism of action is not fully understood but is thought to have central and peripheral mechanism. Acetaminophen is a weak inhibitor of cyclooxygenase enzyme (COX-1 and COX-2) and may be cloned COX-3 enzyme.12 It has few side effects and is entirely metabolized in liver. The usual dosage range of 2600 to 3200 mg/day is safe, and the recommended adult dose is up to 4 g/day. Chronic administration of higher doses is associated with hepatotoxicity (especially in chronic ethanol users, malnutrition, and fasting patients).13

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs are the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide and are commonly used for treating back pain. They possess antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects, the latter two accounting for their use in arthritic and painful disorders. The mechanism of action of NSAIDs includes cyclooxygenase enzyme (COX-1 and COX-2) inhibition, resulting in decreased tissue levels of prostaglandins. NSAIDs also have a central action. Those that inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 include aspirin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen, and piroxicam. NSAIDs that selectively inhibit COX-2 include celecoxib, etodolac, meloxicam, and nimesulide.14 In a systematic review of 65 randomized controlled trials of NSAIDs in low back pain, the authors concluded that NSAIDs were more effective compared with placebo but at the cost of significantly more side effects. There was moderate evidence that NSAIDs were more effective than acetaminophen for acute low-back pain, but acetaminophen had fewer side effects. There was moderate evidence that NSAIDs were not more effective than other drugs for acute low back pain. There was strong evidence that various types of NSAIDs including COX-2 NSAIDs were equally effective for acute low back pain. The data suggested that NSAIDs were effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low back pain without sciatica.15

NSAIDs can have serious side effects on various organ systems including the gastrointestinal tract (gastroduodenal ulceration and bleeding); kidneys (renal insufficiency, salt and water retention, edema, and hypertension); cardiovascular system (peripheral edema, hypertension, and congestive heart failure); and reproductive system (adverse pregnancy outcomes).16–19 The risk of serious gastrointestinal complications such as bleeding or perforation is increased fourfold to fivefold with continued intake of nonselective NSAIDs, and the risk of developing renal failure is twofold. The risk of gastrointestinal complications is increased with age, history of peptic ulcer disease, concomitant corticosteroids, and anticoagulants. The risk of acute renal failure increases with age, history of renal insufficiency, heart failure, hypertension, and use of diuretics or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.20–21

The toxicity associated with chronic NSAID administration limits NSAIDs’ benefit-to-risk ratio. The discovery of isoenzymes of cyclooxygenase, COX-1 (constitutive), and COX-2 (predominant role in inflammation) led to the development of selective COX-2 inhibitors. COX-1 is responsible for generation of cytoprotective prostanoids and is constitutively expressed in platelets and gastroduodenal mucosa.19,21 Thus inhibition of COX-1 leads to the increased risk of gastroduodenal bleeding. Compared with nonselective COX inhibitors, the selective COX-2 inhibitors are associated with reduced incidence and complications related to gastroduodenal ulceration, provided patients are not taking aspirin concomitantly.18,21,22,23 Nonetheless, COX-2 inhibitors were just as effective analgesics as nonselective NSAIDs.15 Misoprostol, a synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), exerts a gastrointestinal mucosal protective effect by increasing mucous, bicarbonate ion secretion, and increasing mucosal blood flow. Concomitant use of Misoprostol or proton pump inhibitors with NSAIDs reduces the risk of gastrointestinal complications.24 Misoprostol is available in tablet form in combination with diclofenac. Misoprostol should be used with caution in females of child bearing age because it can initiate uterine contractions and miscarriage.

The kidney constitutively expresses both COX-1 and COX-2. This may explain why COX-2 inhibitors seem to exhibit a similar renal side effect profile to nonselective NSAIDs. It appears that renal side effects are consequent to the inhibition of COX-2 by NSAIDs.17,22,23

The cardiovascular effects of NSAIDs have caused a major stir since the introduction of COX-2 selective inhibitors (coxibs). There has been increased risk of cardiovascular events with patients using selective COX-2 inhibitors.25–27 This resulted in withdrawal of rofecoxib and valdecoxib. Only celecoxib remains in the market. The possible mechanism of increase in cardiovascular risk seems to be due to the disruption of the normal balance between pro and antithrombotic prostaglandins. Thromboxane A2 is a platelet activator and aggregator that is mediated by prostaglandin products of the COX-1 isomer pathway. Prostaglandin PGI2 vasodilates and inhibits platelet aggregation when the COX-2 isomer is activated. Thrombotic cardiovascular events may follow when thromboxane A2 predominates over PGI2.28 Coxibs use should be avoided in patients with increased cardiovascular risk including patients with recent cardiovascular events, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, and ischemic cerebrovascular events. If coxibs are indicated, the smallest effective dose for the shortest duration should be used. Naproxen may be a better alternative to coxibs.29 Physicians should weigh the risk-to-benefit ratio when prescribing NSAIDs in all patients.

Medicated diclofenac patch is available for topical use in acute musculoskeletal sprains. Use of topical patches for localized pain may reduce the risk of serious adverse events due to low systemic concentration.30

Muscle Relaxants

Skeletal muscle relaxants are commonly used for back pain. They are a heterogeneous group of agents that mainly act on the central nervous system (CNS). At therapeutic doses they seem to exert their effect through sedation and subsequent depression of the neuronal transmission.31 Studies have shown that muscle relaxants are effective when used for short duration in treatment of acute low back pain. There is no evidence for long-term use of muscle relaxants in chronic low back pain.28 Commonly used drugs include cyclobenzaprine, methocarbamol, metaxalone, carisoprodol, diazepam, tizanidine, baclofen, orphenadrine, and chlorzoxazone. The most common adverse effect includes drowsiness and dizziness. Physicians should be aware of possible dependence and abuse of some of the muscle relaxants like diazepam and carisoprodol.32

Antidepressants

Antidepressants have been used widely for managing various painful conditions, mainly neuropathic pain. Antidepressants differ in their effectiveness in pain control depending on whether they inhibit reuptake of serotonin (serotonergic antidepressants like paroxetine, fluoxetine sertraline, and citalopram); norepinephrine (noradrenergic antidepressants like desipramine, nortriptyline, and maprotiline); or both (serotonergic-noradrenergic antidepressants like amitriptyline, doxepin, imipramine, clomipramine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine). Serotonergic-noradrenergic antidepressants were found to be more effective than placebo in chronic low back pain.33–35 The symptom reduction of these drugs in chronic low back pain seems to be independent of their effect on depression. There was conflicting evidence as to whether antidepressants improved the functional status of the patients with chronic low back pain.9 In addition to chronic back pain, antidepressants exhibit an apparent antinociceptive effect in other musculoskeletal conditions including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia.33,34 Antidepressants are associated with significant adverse events, namely drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, and weight gain.36

Duloxetine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has been approved for use in fibromyalgia and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain.37–42 A meta-analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of duloxetine in the treatment of fibromyalgia showed it to be significantly superior to placebo in relieving pain. Adverse effects tend to be mild.

Opioids

Opioids remain the most potent analgesic and are a mainstay in the treatment of acute and chronic painful conditions of moderate to severe intensity. Although their analgesic efficacy is well established, their effect on functional improvement is controversial.43–47 Nociceptive pain is more responsive to opioid therapy than is neuropathic pain. Opioids have been widely used for non–cancer pain including chronic low back pain and radiculopathy. But some important issues need to be addressed with regard to opioid prescription for non–cancer pain, namely the framework in which opioids are prescribed, when to initiate opioid therapy, who the appropriate candidates for opioid therapy are, and what the end point of treatment is.48 In general there is sufficient evidence to suggest that opioid analgesia is safe and effective for the treatment of patients with chronic low back pain, at least for the short duration. The evidence for functional improvement with opioids, however, is limited. Opioids appear to be a reasonable treatment option for patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain that is refractory to general rehabilitation, injections, and nonopioid analgesic medications; for patients with pain that is not directly treatable because of the structural disorder; or because of patient preference.49

Methadone is a potent opioid with a long half-life of more than 24 hours and is therefore used to block withdrawal and treat addiction and pain. For analgesia, it is best given every 6 to 8 hours, on an as-needed basis, rather than at fixed intervals. Because of its long half-life and large variability in its clearance, it tends to accumulate with repeated dosing. Caution should be exercised when increasing the dose and in the elderly.50 The D-isomer of methadone exerts significant antinociception action in neuropathic pain models by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor.51 Fentanyl is an intrinsically short-acting potent µ agonist that is available in a long-acting transdermal (reservoir) form. Onset is slow and stable blood levels are achieved 12 to 17 hours after application. An oral transmucosal form of fentanyl (oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate, fentanyl buccal tablet) has been used in managing breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant cancer pain patients.52 It has a rapid onset of action and should not be used in opioid-naive patients. Longer-acting preparations of morphine and oxycodone are available in controlled-release formulations resulting in sustained effect over 12 to 24 hours.53 The use of controlled-release preparations is recommended in chronic opioid therapy because it results in pain reduction comparable with the immediate-release form but with a significantly lower dosage and better quality of life. Some patients may need additional doses of opioids for breakthrough pain. These doses should not be greater than 10% to 20% of the total 24-hour dose of controlled-release medication. If the patient needs more than three doses for breakthrough pain in a 24-hour period, then the sustained release dose may need to be increased.54–58

Side effects are common with opioids. They include constipation, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, itching, sedation, decreased libido, cognitive blunting, and respiratory depression.58–59 Constipation is the most common side effect. A high-fiber diet and a good bowel regimen is usually necessary when initiating opioid therapy.57–59 Tolerance develops quickly to most of the opioid side effects including sedation, nausea, and respiratory depression. Constipation, sweating, and urinary retention are resistance to tolerance. The cognitive effect of opioids is seen mostly in the beginning of opioid therapy initiation and does not persist beyond a few days. There is consistent evidence of lack of impairment of psychomotor abilities in opioid-maintained patients.49,60 The risk of cognitive dysfunction is highest with acute use and first prescription.

There are several concerns regarding opioid prescriptions including side effects, physical dependency, tolerance, risk of addiction and abuse, diversion, and regulatory issues. Physical dependence is a state of physiologic adaptation resulting in withdrawal symptoms when a medication is abruptly stopped. Opioid withdrawal can result in flulike symptoms, nausea, diarrhea, sweating, mydriasis, tachycardia, hypertension, CNS arousal, and increased pain. Opioid withdrawal may be life threatening if the patient has significant coronary artery disease or metabolic disorder.59 Tolerance is a phenomenon in which the patient develops resistance to the effects of medication with time. It occurs with opioid analgesia and also with its side effects. Patients need to be reassessed before increasing the dose if tolerance is suspected. Increasing dosing requirement in cancer patients may relate to disease progression. If tolerance is significant, opioid rotation may be considered because of incomplete cross tolerance among opioids.48,61 Addiction is a neurobehavioral biologic disorder with loss of control and continued use and craving of drug despite harm. Important genetic, psychological, and sociocultural factors contribute to development of addiction. Patients with the highest risk of prescription opioid addiction are those with history (including family history) of substance or alcohol abuse.62,63 Abuse refers to use of drug outside the intended indication with potential for self-harm or harm to others. Pseudoaddiction refers to an addiction-like behavior by patients seeking higher doses of opioid to control undertreated pain. Pseudoaddiction resolves when a patient obtains adequate analgesia, whereas true addictive behavior does not improve (Table 105–1).64

| Chronic Pain Patient | Addicted Patient |

|---|---|

| Not out of control with medications | Out of control with medications |

| Medications improve quality of life | Medications decrease quality of life |

| Concerned about medical problems | In denial about medical problems |

| Will follow the agreed-upon treatment plan. | Does not follow the treatment plan |

| Has medicine left over from the prior prescription | Short on medications, long on stories |

From Savage SR: Addiction in the treatment of pain: significance, recognition, and management. J Pain Symptom Manage 8:265-278, 1993.

The guidelines for treatment of chronic pain with opioids include careful evaluation of the patient, a treatment plan that states the goal of therapy, informed consent, therapeutic trial, regular follow-up visits, consultation when necessary with specialists, and maintenance of good medical records.49 Caution should be exercised while prescribing opioids to elderly patients, patients with history of hepatic or renal impairment or marked respiratory depression, patients with history of alcohol abuse or drug problems or diversion, and patients with secondary gain issues such as pending disability or litigation. The goal or treatment should include partial analgesia, with the understanding that functional improvement may not occur. Adjuvant medications (NSAIDs, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants) may be used in conjunction with opioids to reduce the opioid requirement. Maintaining a high index of suspicion for abuse with patients who call frequently or lose prescriptions often and obtaining random urine toxicology screens are useful measures to avert abuse, addiction, or diversion problems with opioid therapy.

Tramadol

Tramadol is a nonscheduled opioid that is a synthetic analogue of codeine. It is a weak µ receptor agonist with a receptor affinity of 6000-fold less than morphine. In spite of being a weak opioid receptor agonist, the relative potency of tramadol in acute pain ranges between  and

and  that of morphine. Tramadol inhibits uptake of norepinephrine and serotonin in the CNS, which may contribute to its additional analgesic effect. It does not inhibit cyclooxygenase and hence does not share the gastrointestinal or renal side effects of NSAIDs.65–67 Tramadol has been shown to be effective in treatment of patients with chronic low back pain.68,69 It may be useful in neuropathic conditions like diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia.70

that of morphine. Tramadol inhibits uptake of norepinephrine and serotonin in the CNS, which may contribute to its additional analgesic effect. It does not inhibit cyclooxygenase and hence does not share the gastrointestinal or renal side effects of NSAIDs.65–67 Tramadol has been shown to be effective in treatment of patients with chronic low back pain.68,69 It may be useful in neuropathic conditions like diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia.70

The adverse effects of tramadol reflect its dual mechanism of action, namely opioid effects (dizziness, headache, sweating, and dry mouth) and monoaminergic effects (dizziness, headache, sweating, and dry mouth). Clinically significant respiratory depression is almost never seen with clinically effective doses of tramadol, and the risk of constipation is markedly low.65,66 The effective oral dose is 200 to 400 mg/day in divided doses every 6 hours. Extended-release formulation71,72 and combination with acetaminophen are also available.69 Dosing must be reduced in elderly patients and in patients with significant renal and hepatic impairment.67 Seizure is the most serious side effect of tramadol which is predisposed by history of epilepsy, head trauma, metabolic disturbance, drug or alcohol withdrawal, and concurrent CNS infection. Seizures and serotonin syndrome may occur in patients taking tramadol and antidepressants, which inhibits serotonin uptake. Caution should therefore be used when tramadol and antidepressants are used concomitantly. Discontinuing antidepressants may be considered.65,67,73

Antiepileptics

Antiepileptics are most commonly used in the treatment of painful neuropathic conditions. U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved anticonvulsants for specific conditions include carbamazepine (trigeminal neuralgia); gabapentin (postherpetic neuralgia); pregabalin (postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia); divalproex (migraine prophylaxis); and topiramate (migraine prophylaxis).74 They exert their effect by blocking neuronal transmission through effects on various ion channels and receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. Although anticonvulsants are commonly used to treat radicular pain, the data supporting the evidence of their use is sparse and no antiepileptics are FDA approved for chronic low back pain.9,36 Gabapentin is an alpha2-delta ligand and acts on voltage-gated calcium channels. Dosing requires slow titration starting at 100 to 300 mg per day up to a maximum of 3600 mg per day in divided doses.9,75–77 Pregabalin is also an alpha2-delta ligand that acts on voltage-gated calcium channels. It can be started with 50 to 75 mg twice daily and titrated up to 300 to 600 mg per day.8,9,78–80 Topiramate blocks voltage-gated sodium channels, potentiates GABA transmission, and inhibits excitatory neurotransmission. Doses of 300 mg per day help reduce pain symptoms and improve mood and quality of life.81,82 Topiramate is also associated with mild weight loss. The common side effects of gabapentin and pregabalin include somnolence, dizziness, confusion, ataxia, fatigue, peripheral edema, and weight gain. Side effects of topiramate include paresthesia, fatigue, weakness, sedation, dizziness, and diarrhea.9 Dosage should be reduced, and slower titration is necessary in elderly patients and in patients with significant hepatic and renal impairment.83

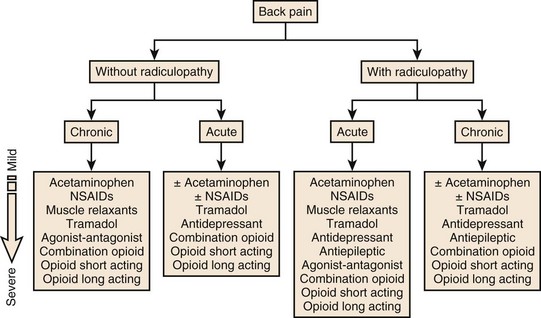

An algorithm for the management of acute and chronic low back pain with or without radiculopathy based on current available evidence is summarized in Figure 105–1.

Other Treatments and Future Prospects

Oral and parenteral corticosteroids are frequently administered in acute back pain and radiculopathy, but their efficacy must be proven.84–86 To counter the cardiovascular side effects of NSAIDs, newer ones are being considered including nitric oxide-NSAIDs (NO-NSAIDs), dual cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) inhibitors, and anti-TNF-α therapy.14 Newer tamper-resistant opioids are being developed to reduce abuse, misuse, and diversion. Multiple molecular entities have been developed including glutamate antagonists, cytokine inhibitors, vanilloid-receptor agonist, catecholamine modulators, ion channel blockers, acetylcholine modulators, cannabinoids, opioids, adenosine receptor agonists, and others.88 Molecular approaches to neuropathic pain include cell and gene therapies, antibodies, and ribonucleic acid interference (RNAi)-based treatments. Some of the novel targets for developing therapies for neuropathic pain include chemokine receptors, glial cells, and cytokines. Emergence of biologic approaches offers new therapeutic additions to address different painful conditions.88,89

Key Points

1 Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33:1766-1774.

2 Chou R, Huffman LH. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/ American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514.

3 Roberts HD, Alec B, O’Connor, Miroslav B, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237-251.

Discusses the recommendations for neuropathic pain.

4 Maier C, Hildebrant J, Klinger R, et al. Morphine responsiveness, efficacy and tolerability in patients with chronic non-tumor associated pain- results of double-blind placebo- controlled trial (MONTAS). Pain. 2002;97:223-233.

Randomized controlled trial that discusses opioid use in non–cancer pain.

5 Chang V, Gonzalez P, Akuthota V. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with adjunctive analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:21-27.

1 Katz JN. Lumbar Disc disorders and low-back pain; Socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88A(suppl 2):21-24.

2 Research on low back pain and common spinal disorders. NIH guide. 16, 1997.

3 Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, et al. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in United States. Spine. 2004;29:79-86.

4 Davis H. Increasing rates of cervical and lumbar spine surgery in the United States, 1979-1990. Spine. 1994;19:1117-1123.

5 Dellemijn P. Are opioids effective in relieving neuropathic pain? Pain. 1999;80:453-462.

6 Wallace MS. Pharmacologic treatment of neuropathic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:138-150.

7 Bridges D, Thompson SW, Rice AS. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:12-26.

8 Roberts HD, Alec B, O’Connor, Miroslav B, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237-251.

9 Chang V, Gonzalez P, Akuthota V. Evidence- informed management of chronic low back pain with adjunctive analgesics. The Spine Journal. 2008;8:21-27.

10 Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain in the primary care: an international comparison. Spine. 2001;26:2504-2513.

11 Bijlsma JW. Analgesia and the patient with osteoarthritis. Am J Ther. 2002;9:189-197.

12 Botting RM. Mechanism of action of acetaminophen; is there a cycloxygenase 3? Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(Suppl 5):S202-S210.

13 Bertin P, Keddad K, Jolivet-Landreau I. Acetaminophen as symptomatic treatment of pain from osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:266-274.

14 Rao P, Kanus EF. Evolution of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition and beyond. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2008;11:81s-110s.

15 Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33:1766-1774.

16 Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia- Rodriguez LA. Epidemiologic assessment of the safety of conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 2001;110(Suppl 3A):20S-27S.

17 Appel GB. COX-2 inhibitors and the kidney. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:S37-S40.

18 Hawkey CJ. NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors; what can we learn from the large outcome trials? The gastroenterologist’s perspective. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:S23-S30.

19 Fitzgerald GA, Cheng Y, Austin S. COX-2 inhibitors and the cardiovascular system. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:S31-S36.

20 Hernandez-Diaz S, Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/ perforation: An overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern med. 2000;160:2093-2099.

21 Hochberg MC. What have we learned from the large outcomes trials of COX-2 selective inhibitors? The rheumatologist’s perspective. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:S15-S22.

22 Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR study group. N Eng J Med. 2000;343:1520-1528. 2

23 Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study; A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 2000;284:1247-1255.

24 Targownik LE, Metge CJ, Leung S, Chateau DG. The relative efficacies of gastroprotective strategies in chronic users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):937-944.

25 Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092-1102.

26 Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1071-1080.

27 Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al. Complications of COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1081-1091.

28 Malanga G, Wolff E. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and simple analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:173-184.

29 Vardeny O, Solomon SD. Cycloxygenase-2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cardiovascular risk. Cardiol Clin. 2008;26(4):589-601.

30 Rainsford KD, Kean WF, Ehrlich GE. Review of pharmaceutical properties and clinical effects of the topical NSAID formulation, diclofenac epolamine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2967-2992.

31 Waldman HJ. Centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxants and associated drugs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994;9:434-441.

32 Beebe FA, Barkin RL, Barkin S. A clinical and Pharmacologic Review of Skeletal Muscle Relaxants for Musculoskeletal Conditions. Am J Ther. 2005;12:151-171.

33 Fishbain D. Evidence based data on pain relief with antidepressants. Ann Med. 2000;32:305-316.

34 Teasell RW, Merskey H, Deshpande S. Antidepressants in rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1999;10:237-253. vii

35 Salerno SM, Browning R, Jackson JL. The effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain: a meta- analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:19-24.

36 Chou R, Huffman LH. Medications for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: A review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/ American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514.

37 Acuna C. Duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44:725-734.

38 Sumpton JE, Moulin DE. Fibromyalgia: presentation and management with a focus on pharmacological treatment. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:477-483.

39 Wernicke JF, Pritchett YL, D’Souza DN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Neurology. 2006;67:1411-1420.

40 Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F, et al. A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:346-356.

41 Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Lee TC, Iyengar S. Duloxetine vs placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2005;116:109-118.

42 Fishbain D, Berman K, Kajdasz DK. Duloxetine for neuropathic pain based on the recent clinical trials. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10:199-204.

43 Moulin DE, Iezzi A, Amireh R, et al. Randomised trial of oral morphine for chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet. 1996;347:143-147.

44 Roth SH, Fleischmann RM, Burch FX, et al. Around-the-clock, controlled-release oxycodone therapy for osteoarthritis-related pain: placebo-controlled trial and long term evaluation. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:853-860.

45 Caldwell JR, Hale ME, Boyd RE, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis pain with controlled release oxycodone or fixed combination oxycodone plus acetaminophen added to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a double blind, randomized, multicenter, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:862-869.

46 Schofferman J. Long-term opioid analgesic therapy for severe refractory lumbar spine pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:136-140.

47 Maier C, Hildebrant J, Klinger R, et al. Morphine responsiveness, efficacy and tolerability in patients with chronic non-tumor associated pain—results of double-blind placebo-controlled trial (MONTAS). Pain. 2002;97:223-233.

48 Savage SR. Opioid use in the management of chronic pain. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:761-786.

49 Schofferman J, Mazanec D. Evidence informed management of chronic low back pain with opioid analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:185-194.

50 Foley KM, Houde RW. Methadone in cancer pain management: individualize dose and titrate to effect. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3213-3215.

51 Shimoyama N, Shimoyama M, Elliott KJ, et al. d-Methadone is antinociceptive in the rat formalin test. J Pharmocol Exp Ther. 1997;283:648-652.

52 Messina J, Darwish M, Fine PG. Fentanyl buccal tablet. Drugs Today. 2008;44:41-54.

53 Reder RF. Opioid formulations: tailoring to the needs in chronic pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(Suppl A):109-111.

54 Hale ME, Fleischmann R, Salzman R, et al. Efficacy and safety of controlled-release versus immediate-release oxycodone: randomized, double-blind evaluation in patients with chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:179-183.

55 Lazarus H, Fitzmartin RD, Goldenheim PD. A multi-investigator clinical evaluation of oral controlled-release morphine (MS Contin) administered to cancer patients. Hosp J. 1990;6:1-15.

56 Cundiff D, McCarthy K, Savarese JJ, et al. Evaluation of a cancer pain model for the testing of long-acting analgesics. The effect of MS Contin in double-blind, randomized crossover design. Cancer. 1989;63:2355-2359.

57 Hisgen WJ. Long-term opioid analgesia and chronic non-cancer pain. WMJ. 2001;100:17-21.

58 Portenoy RK. Opioid therapy for chronic non-malignant pain: a review of critical issues. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:203-217.

59 Brown RL, Fleming MF, Patterson JJ. Chronic opioid analgesic therapy for chronic low back pain. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1996;9:191-204.

60 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. re opioid-dependent/tolerant patients impaired in driving-related skills? A structured evidence-based review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:559-577.

61 Indelicato R, Portenoy RK. The art of oncology: when the tumor is not the target. Opioid rotation in the management of refractory cancer pain. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:348-352.

62 Aronoff GM. Opioids in chronic pain management: is there a significant risk of addiction? Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:112-121.

63 Reid MC, Engles-Horton LL, Weber MB, et al. Use of Opioid medications for chronic non cancer pain syndromes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:173-179.

64 Weissman DE, Haddox JD. Opioid pseudoaddiction- an iatrogenic syndrome. Pain. 1989;36:363-366.

65 Bamigbade TA, Langford RM. Tramadol hydrochloride: an overview of current use. Hosp Med. 1998;59:373-376.

66 Shipton EA. Tramadol—present and future. Anesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:363-374.

67 Gibson TP. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of analgesia with a focus on tramadol Hcl. AM J Med. 1996;101:47S-53S.

68 Schnitzer TJ, Gray WL, Paster RZ, et al. Efficacy of tramadol in the treatment of chronic low back pain. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:772-778.

69 Peloso PM, Fortin L, Beauleiu A, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets (Ultracet) in the treatment for chronic low back pain: a multi center, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2454-2463.

70 Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy. Neurology. 1998;50:1842-1846.

71 Hair PI, Curran MP, Keam SJ. Tramadol extended-release tablets. Drugs. 2006;66:2017-2027.

72 Vorsanger GJ, Xiang J, Gana TJ, et al. Extended release tramadol (tramadol ER) in the treatment of chronic low back pain. J Opioid Manag. 2008;4:87-97.

73 Lewis KS, Han NH. Tramadol: a new centrally acting analgesic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54:643-652.

74 Benzon H, Rathmell J, Wu C, et al, editors. Raj’s Practical Management of Pain, 4th ed. St Louis: Elsevier. 2008:p 660. Table 34-1

75 Yildirim K, Sisecioglu M, Karatay S, et al. The effectiveness of gabapentin in patients with chronic radiculopathy. Pain Clin. 2003;15:213-218.

76 Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1831-1836.

77 Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, et al. Gabapentin for treatment for postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1837-1842.

78 Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ, Otte A, et al. Pregabalin in central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury: a placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;67:1792-1800.

79 Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JPJr, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:1274-1283.

80 Tölle T, Freynhagen R, Versavel M, et al. Pregabalin for relief of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind study. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:203-213.

81 Khoromi S, Patsalides A, Parada S, et al. Topiramate in chronic lumbar radicular pain. J Pain. 2005;6:829-836.

82 Muehlbacher M, Nickel MK, Kettler C, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:526-531.

83 Tremont-Lukats IW, Megeff C, Backonja MM. Anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain syndromes: mechanisms of action and place in therapy. Drugs. 2000;60:1029-1052.

84 Friedman BW, Holden L, Esses D, et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for emergency department patients with non-radicular low back pain. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:365-370.

85 Deyo RA. Drug therapy for back pain. Which drugs help which patients? Spine. 1996;21:2840-2849.

86 Von Feldt JM, Ehrlich GE. Pharmacologic therapies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1998;9:473-487.

87 Gilron I, Coderre TJ. Emerging drugs in neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:113-126.

88 Jain KK. Current challenges and future prospects in management of neuropathic pain. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:1743-1756.

89 Dray A. Neuropathic pain: emerging treatments. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:48-58.

90 Savage SR. Addiction in the treatment of pain: significance, recognition, and management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:265-278.