Chapter 56 Petrosal Approach

Petroclival tumors arise from or involve the petroclival junction cephalad from the jugular tubercle, medial to the trigeminal nerve, and anteromedial to the internal auditory canal (IAC).1,2 Tumors of the petroclival area are a particular challenge because these tumors often involve the middle and posterior cranial fossae, cause significant brainstem compression, invade the cavernous sinus, and abut or surround the upper cranial nerves and basilar artery. The complex anatomy requires an individualized surgical approach for each patient based on tumor origin, area of tumor extension, and preoperative neural function.3

The term combined petrosal approach actually describes numerous surgical approaches to the petroclival area well suited for these tumors. The term combined refers to the fact that this approach combines the middle fossa approach with a variation of a posterior fossa approach. The combination of these approaches allows for excellent exposure of the medial petrous bone and clivus from the cavernous sinus to the foramen magnum. First described by Decker and Malis,4 this combination allows the surgeon to take advantage of the strengths of each approach to minimize brain retraction. The middle fossa approach gives the surgeon good exposure of the petrous bone and clivus superior to the IAC, whereas the posterior approach provides surgical exposure inferior to the IAC. A tumor that is superior to the IAC can be accessed by a middle fossa approach alone. A tumor that is inferior to the IAC and tentorium cerebelli can be addressed with a posterior approach alone. It stands to reason that tumors involving both areas are best treated with a combination of these surgical procedures.

COMBINED PETROSAL VARIATIONS

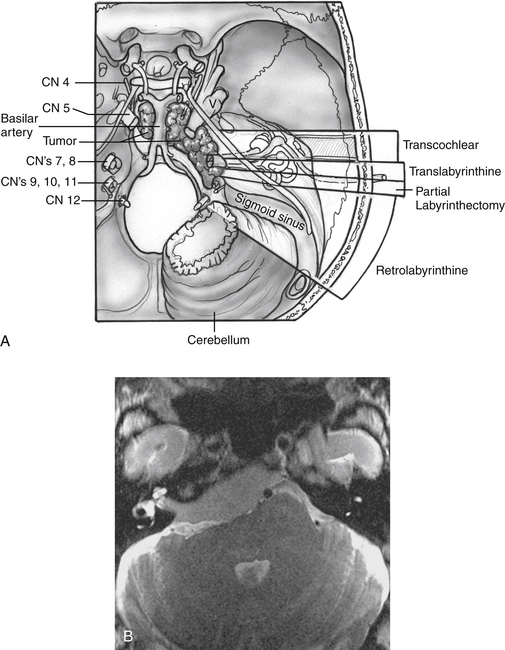

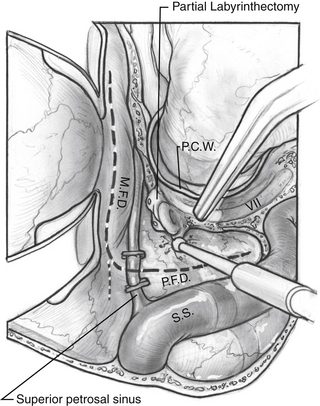

All of the combined petrosal approaches include similar middle fossa exposure as a component of the procedure. The variations of the combined petrosal approach are classified by the type of posterior approach used. Traditionally, three variations of the combined petrosal approach were described: the retrolabyrinthine, translabyrinthine, and transcochlear approaches.5,6 The fourth variation described by Sekhar and colleagues,7 which provides exposure in between the retrolabyrinthine approach and the translabyrinthine approach, uses a partial labyrinthectomy for the posterior approach. This approach removes most of the labyrinth, while preserving functional hearing in 80% of patients. These four approaches give different degrees of anterior petrous bone exposure, which changes the level of brainstem and clivus exposure. The narrow angle between the anterior brainstem and clivus is the major factor influencing the level of visualization across both of these structures. Generally, further anterior removal of the otic capsule allows a more direct angle across the clivus, allowing improved medial exposure to the brainstem, basilar artery, and central clival depression. More aggressive anterior otic capsule removal secondarily provides improved access to the ipsilateral medial petrous bone as well (Fig. 56-1A).

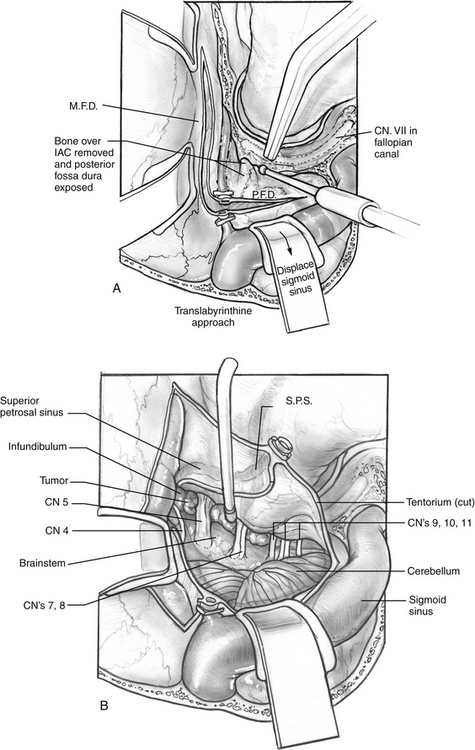

The choice of posterior approach depends on tumor location and size, preoperative hearing level, and extent of brainstem compression. The translabyrinthine and transcochlear approaches sacrifice residual hearing. The transcochlear approach also includes posterior facial nerve transposition, leading to a temporary facial paralysis and risking permanent injury. The translabyrinthine approach is used when preoperative hearing is poor, and the transcochlear approach is reserved for the largest of tumors that cross the midline of the clivus. Tumor effect on the brainstem is also an important consideration. Sometimes larger tumors need a less radical posterior approach because the posterior compression of the brainstem opens the angle between the clivus and brainstem. The tumor in Figure 56-1B was addressed with a translabyrinthine variation of the combined petrosal approach despite involvement of the contralateral clivus. The posterior displacement and contralateral displacement of the brainstem kept the angle between the tumor-involved clivus and brainstem open, obviating the need for a transcochlear approach.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

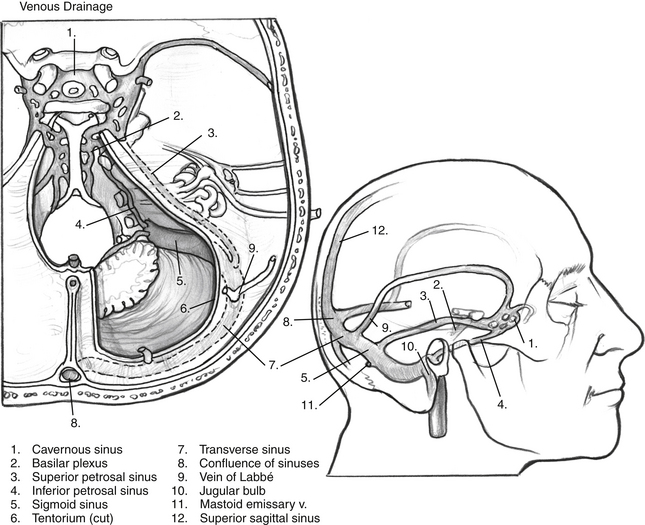

Important temporal bone arterial and venous variations can often be detected from MRI; however, angiography with venous phase should be considered for each patient in whom a combined petrosal approach is being contemplated. Important venous anomalies exist that may result in catastrophe if not recognized before surgery.8 The main venous drainage of the temporal lobe is through the vein of Labbé, a single tributary that runs along the inferior surface of temporal lobe and typically anastomoses into the transverse sinus. The vein of Labbé may run through the tentorium, however, and insert into the superior petrosal sinus, rather than the transverse sinus. Because superior petrosal vein and tentorium transection is a key component of the combined petrosal approach, the vein of Labbé would be at risk if this anatomic variation is present. Accidental transection can lead to venous infarction of the temporal lobe with particularly grave consequences to the patient, especially if it occurs in the dominant hemisphere. A dominant sigmoid sinus should also be recognized before surgery. The surgeon must exercise extra caution not to injure a dominant sigmoid sinus because the contralateral venous drainage may be insufficient or absent, leading to a high risk of venous infarction.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Posterior Exposure

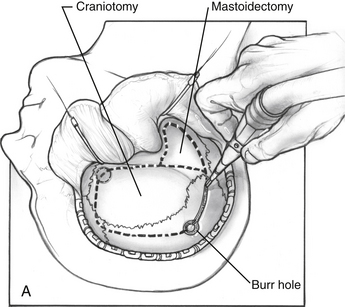

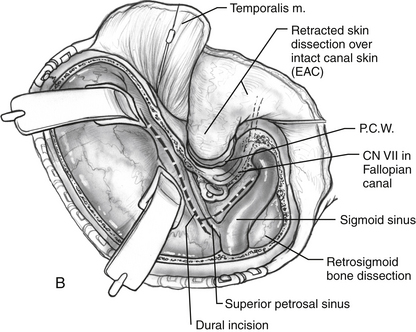

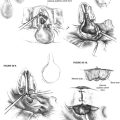

The middle fossa craniotomy or the posterior temporal bone approach may be started first; however, the author finds that beginning with the posterior approach facilitates the middle fossa craniotomy by identifying the level of the middle fossa and limiting the number of burr holes required to turn the middle fossa flap (Fig. 56-2A). A complete mastoidectomy is performed with an electric high-speed drill, and all of the bone covering the middle and posterior fossa dura is removed. Suction irrigation is used, and the irrigant should contain bacitracin to prevent infection and the incidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.9 It is important to remove the bone over the sigmoid sinus and at least 5 mm of bone posterior to the sigmoid to aid with posterior retraction of the sinus. The mastoid emissary vein is divided to facilitate the retrosigmoid bone removal. The bone from the distal transverse sinus should be removed for identification, but the surgeon should use caution to preserve the insertion of vein of Labbé. Wide exposure laterally at the sigmoid greatly facilitates instrumentation medially when the exposure is complete.

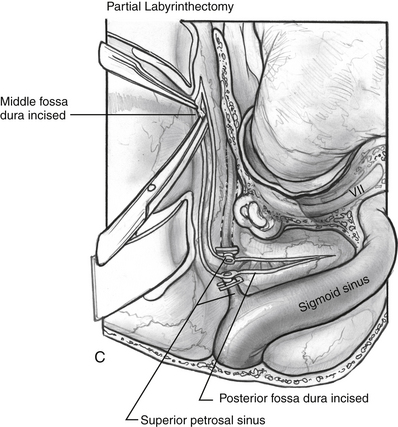

If a retrolabyrinthine approach is chosen, the labyrinth should be skeletonized (Fig. 56-2B). The horizontal canal is identified and followed to the posterior canal. The bone over the superior canal is also removed. The bone covering the posterior fossa dura is removed from the petrosal vein to the jugular bulb. The bone over the middle fossa dura is also removed. The neurosurgeon can perform the middle fossa craniotomy, make the dural incisions, divide the greater petrosal vein, and begin to divide the tentorium to connect the middle and posterior fossae (Fig. 56-2C).

If more exposure is needed, a partial labyrinthectomy can be performed by carefully plugging the semicircular canals as they are drilled away (Fig. 56-3). The key is to avoid exposure and traumatic suctioning of the labyrinthine fluids by keeping the labyrinth sealed while removing bone. The superior, horizontal, and posterior canals are skeletonized and blue-lined, but not entered. Bone wax is placed on the end of a 3 mm smooth diamond bit and advanced through the thin bone of the posterior canal to seal it while drilling at slow speed. More wax is placed on the drill bit and advanced inferiorly toward the vestibule, but halted posterior to the facial nerve. The drilling continues superiorly to the common crus. The wax is advanced while drilling at slow speed to the superior semicircular canal. The horizontal canal is also sealed in this fashion. The wax that is placed advances through the membranous labyrinth keeping it sealed as bone is removed. Drilling is stopped short of entering the vestibule, or hearing would be compromised. This technique can give almost the same exposure to the brainstem and clivus as a translabyrinthine approach, although it does not provide access to the IAC.

If hearing is poor, or the IAC is significantly involved with tumor, the translabyrinthine approach is the preferable posterior exposure (Fig. 56-4A). Hearing is sacrificed as a result of this procedure. The semicircular canals are removed starting with the horizontal canal, which is followed posteriorly to identify the posterior canal. The anterior half of the horizontal canal is left to protect the second genu of the facial nerve. The common crus is followed to identify the superior semicircular canal. The semicircular canals are followed into the vestibule, which forms the lateral extent of the IAC. The posterior fossa bone is removed off the dura until the IAC is identified. The bone surrounding the IAC is removed with a diamond drill. The IAC should be exposed about 270 degrees, just as for a translabyrinthine approach for an acoustic tumor. The middle fossa craniotomy is performed, and the tentorium divided as shown in Figure 56-4B.

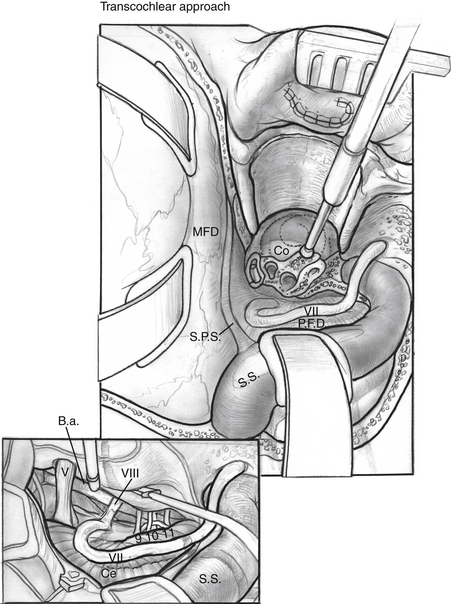

Exposure across the brainstem to the contralateral clivus can be maximized by extending the petrosal bone dissection anteriorly with a transcochlear approach. The external auditory canal is transected at the level of the bony-cartilaginous junction, and the canal skin is everted, and then oversewn in two watertight layers. The posterior external auditory canal wall is removed, as are the remaining canal skin, tympanic membrane, and ossicles. The inferior tympanic ring is also removed with the drill. The facial nerve must be mobilized by removing the bone of the IAC, tympanic fallopian canal, and mastoid segment of the fallopian canal. Bone removal should be greater than 180 degrees at all parts of the fallopian canal. The greater superficial petrosal nerve is sectioned anterior to the geniculate ganglion, and the facial nerve is mobilized posteriorly. There is usually bleeding at the canal of the greater superficial petrosal nerve, which must be packed with bone wax. The dura of the IAC is incised whether or not tumor involves the IAC to allow full posterior facial nerve mobilization. The cochlea is drilled away, and the carotid artery is identified (Fig. 56-5). When the carotid canal is exposed, the anterior petrous bone can be drilled away medially.

One advantage of the combined petrosal approach is that transcochlear exposure is rarely needed except for the largest tumors. Transposition of the facial nerve has an inherent risk of facial nerve injury.10 This variation is carefully considered only when the translabyrinthine exposure is inadequate.

Middle Fossa Exposure

The neurosurgeon usually performs the middle fossa exposure. To facilitate temporal lobe retraction, furosemide, 10 mg, followed by mannitol, 0.5 g/kg, is given intravenously 20 minutes before the middle fossa craniotomy. Burr holes are made as shown in Figure 56-2A, and a side cutting burr with a footplate is introduced into the defect. The craniotomy should be large, following the squamosal suture line. A large craniotomy helps to minimize the temporal lobe retraction required. The craniotomy is centered over the zygomatic arch to ensure adequate anterior exposure. The dura is elevated from posterior to anterior and medially over the remaining bone of the petrous ridge. The middle meningeal artery is coagulated to allow anterior dural elevation. The bone between the trigeminal nerve and IAC is removed (Kawase’s triangle). The dura is divided in the posterior fossa from the jugular bulb and in the middle fossa dura to the superior petrosal vein. The superior petrosal vein is divided connecting the middle and posterior compartments, and the tentorium is sectioned from posterior to anterior. CN IV runs with the tentorium medially, and caution is needed to preserve it. When the tumor is exposed, excision proceeds with microdissection technique, debulking the tumor until the capsule can be visualized and safely dissected from cranial nerves, the brainstem, and arteries. The most challenging areas of dissection are the posterior cavernous sinus, tumor-involved upper cranial nerves, and tumor-involved basilar artery.

CLOSURE

The middle fossa and presigmoid dura are reapproximated as well as possible. Typically, the middle fossa dura is able to be closed adequately enough to prevent CSF leak, but suturing the presigmoid dura is difficult, and the closure needs to be augmented with fat. Abdominal fat is used for this purpose and is placed though the dural defects in a dumbbell fashion. Prevention of CSF leak through the middle ear and eustachian tube varies by what posterior approach was used for the case. Hydroxyapatite cement has been helpful in preventing CSF leak in acoustic tumor surgery, and is used when appropriate for the combined approaches as well.11

RESULTS

Results vary depending on the pathology of the tumor. Meningiomas constitute most of these tumors, and outcomes are well described in the literature. Gross total excision can be accomplished in most cases; however, there are a few reports of good long-term results with subtotal excision to preserve cranial nerves followed by stereotactic irradiation if necessary.12 Gross total excision is preferable if possible because of the difficulty in managing recurrent disease in this area. If tumor invades the cavernous sinus, a small amount can be left because of the morbidity of surgery in this area. If tumor is firmly attached to a cranial nerve, but separated from the brainstem, clivus, and petrous bone, a small piece of the capsule may be left with little concern about growth. Stereotactic irradiation can be used for small residual disease or recurrences that show growth during follow-up.

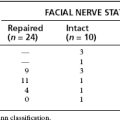

The most common complication of the combined petrosal approach is cranial nerve injury. The most commonly injured cranial nerves are CN V and VII. CN IV and VI can also be injured resulting in diplopia. Lower cranial nerve injury can result in dysphagia postoperatively. Rarely, preoperative deficits may improve after surgery, typically in nerves with partial dysfunction caused by nerve traction that is relieved by tumor excision. Generally, preoperative deficits do not improve, however. In the University of Utah series, 5 of 19 patients (26%) had at least one new, long-standing postoperative cranial nerve deficit.13 Most patients had preoperative cranial nerve function preserved, however. Gross total excision was accomplished in 86% of all patients. Functional hearing was preserved in 85% of patients.

CSF leak is also a common complication of this approach. The rate of CSF leak varies by report, but is approximately 15% to 19%.5,6,13 Most of these cases resolve after placement of a lumbar drain for 3 days. There are not enough data to determine if the success of hydroxyapatite closure in preventing CSF leak after acoustic tumor surgery will translate to the combined petrosal approach.

Cerebrovascular accident is a rare, but serious complication of the combined petrosal approach. Venous infarction is a specific complication that can occur if the sigmoid is injured on a dominant or noncommunicating side, or if the vein of Labbé is injured. Avoidance of these complications is maximized by knowledge of the cerebral venous drainage system (Fig. 56-6) and with preoperative imaging to assess the patient’s specific vascular anatomy.

1. Al-Mefty O. Operative Atlas of Meningiomas. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

2. Abdel Aziz K.M., Sanan A., van Loveren H.R., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: Predictive parameters for transpetrosal approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:139-152.

3. Arriaga M.A., Shelton C., Nassif P., Brackmann D.E. Selection of surgical approaches for meningiomas affecting the temporal bone. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:738-744.

4. Decker R.E., Malis L.I. Surgical approach to midline lesions at base of skull. J Mt Sinai Hosp. 1970;37:84-102.

5. Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T. The combined supra- and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: Experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588-599.

6. Daspit C.P., Spetzler R.F., Pappas C.T. Combined approach for lesions involving the cerebellopontine angle and skull base: Experience with 20 cases—preliminary report. Otol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:788-796.

7. Sekhar L.N., Schessel D.A., Bucar S.D., et al. Partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach to neoplastic and vascular lesions of the petroclival area. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:537-552.

8. Erkmen K., Pradvdenkova S., Al-Mefty O. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: Factors determining the choice of approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:1-12.

9. Kartush J.M., Cannon S.C., Bojrab D.I., et al. Use of bacitracin for neurotologic surgery. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:1050-1054.

10. Selesnik S.H., Abraham M.T., Carew J.F. Rerouting of the intratemporal facial nerve: An analysis of the literature. Am J Otol. 1996;17:793-809.

11. Arriaga M.A., Chen D.A., Burke E.L. Hydroxyapatite cement cranioplasty in translabyrinthine acoustic neuroma surgery-update. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:538-540.

12. Natarajan S.K., Sekhar L.N., Schessel D., Morita A. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:965-979.

13. Baugh A., Hillman T.A., Shelton C. Combined petrosal approaches in the management of temporal bone meningiomas. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:236-239.