Chapter 6 Personal (clinician) responses to risk

Within health care, clinicians are exposed to risks every day. Patients are exposed to risk, clinicians take risks and they sometimes put themselves at risk. Occasionally (perhaps often) clinicians feel that they carry all the risk or they find themselves saying, ‘We can’t take the risk’. Murphy (2002) comments, ‘Apart from the need to assess and manage risk, it also has an emotional component for all concerned and often a judgmental aspect.’1 Undrill (2007) says, ‘Risk assessment has become a large and anxiety provoking part of the work of many psychiatrists.’2

The risk thermostat3

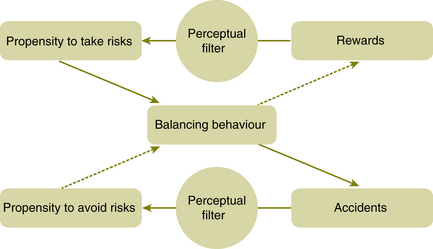

The risk thermostat is a conceptual, qualitative model of how behaviour in risky situations is influenced by perceptions and attitudes. Cultural theory explains risk-taking behaviour by the operation of filters. It postulates that behaviour is governed by the probable costs and benefits of alternative courses of action which are perceived through filters formed from all the previous incidents and associations in the risk-taker’s life. This is shown diagrammatically in Figure 6.1.

Exercise 1

Below is a continuum which can be useful to consider when faced with a risk problem. The continuum characterises the alternative courses of action which will have been considered when risk decisions were taken previously. It allows for a consideration of where your risk thermostat is set at any given time and how the setting may change in different circumstances.

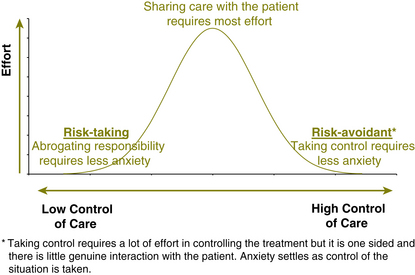

This is shown diagrammatically in Figure 6.3

In practice, it is more common to veer towards the risk-avoidant end of the continuum as this is driven not just by anxiety, but also high workload and limited knowledge base. Clinicians at the risk-taking end of the continuum are more likely to be working in situations where higher levels of risk are dealt with on a daily basis and they become desensitised to the level of risk; for example, crisis teams and inpatient units.

Personal factors that may affect risk management

Most clinicians have learnt to identify and manage the personal factors that may affect risk management although they may be forgotten in the heat of the moment.

Here is a list of personal factors in the clinician which may affect the context of risk:

• fear/anxiety and emotional response to the situation

• competence and factual knowledge of clinician:

• mindset of clinician: ‘I should be able to save all of my patients’

It is likely that these factors are additive.

Exploring personal factors in more detail

Fear/anxiety and emotional response to risk

Risk is synonymous with danger for many clinicians. If risk is perceived as dangerous, not as something to be assessed and managed with the patient, clinicians are likely to respond as if there is a personal threat. It may be in the form of danger from perceived attack, being stalked or from a fear of loss of registration if a suicide occurs. It is not only danger in the form of physical attack; personality disordered patients intrude on clinicians’ feelings and can affect the assessment. However, it would be wrong to ignore the fact that many clinicians are exposed to danger where there is a risk of personal harm. This can occur in many settings. The response to danger is invariably one of fear (‘survival anxiety’)4 but there may also be a loss of mental wellbeing from stress. Clinicians may also fear being blamed or fear personal and professional disgrace. If clinicians allow anxiety to affect risk management, it is likely that they will slip into secondary risk management (see glossary) which will have a ‘corrosive effect on the relationship between the clinician and patient’.5

Patients can then be blamed (using externally directed hostility)6 for their problems or treated as consciously creating the problem. For example, ‘she’s just being manipulative’ or ‘he’s just personality disordered, not mentally ill’. Other common defences are to say, ‘it’s just a drug-induced psychosis’ or ‘this patient should be in forensics’. Anxious clinicians cannot reflect on what they are doing which will further reduce capacity for good risk assessment.

Mindset of clinician: ‘I should be able to save all of my patients’

To carry this mindset which has been described as an ‘over inflated concept of duty of care’7 is a recipe for burnout and rescuing behaviour on the part of the clinician. Although at times families, coroners and the media expect clinicians to prevent all suicides, this is not possible and the task is not to save all patients but to do the best within the limitations of the individual and the service.

Workload of clinician

This point is self evident but can have a substantial effect on the capacity to manage risk. Making decisions at 3 a.m. is a different experience to making the same decisions at 3 p.m. Clinicians should be mindful of

BOX 6.2 PERSONAL RESPONSES TO RISK

• If risk is managed by reducing clinician anxiety (secondary risk management), the risk to the patient may increase.

• If clinician/patient discomfort is reduced indiscriminately, opportunities for learning from and improving the symptoms may also be reduced.

• ‘In order to achieve therapeutic gain, it is sometimes necessary to take risks. A strategy of total risk avoidance can lead to excessively restrictive management, which may in itself be damaging to the individual.’8

the affect that their workload and tiredness is having on their decision-making.

1 Murphy D. Risk assessment as collective clinical judgment. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2002;12:169–178.

2 Undrill G. The risks of risk assessment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:291–297.

3 Adams J. Risk. London: Routledge Publications; 1995.

4 Nitsun M. The Anti-Group. Destructive Forces in the Group and their Creative Potential. London: Routledge; 1996.

7 Carroll A. Are violence risk assessment tools clinically useful? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:301–307.

8 New Zealand Ministry of Health. Guidelines for Clinical Risk Assessment and Management in Mental Health Services. New Zealand Ministry of Health. 1998.