Chapter 9 Periumbilical Perforator Sparing Components Separation ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

1 Rationale for Sparing the Periumbilical Perforators

Components separation for ventral hernia repair requires release of the external oblique muscle lateral to the linea semilunaris and separation of the avascular plane deep to the external oblique. This allows midline advancement of the rectus abdominis in continuity with the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. As originally described, components separation requires wide undermining of the skin and subcutaneous layer to adequately expose the external oblique muscles for subsequent division. Consequently, perfusion of the undermined skin flaps can be compromised, which increases the risk of skin flap necrosis, infection, and dehiscence. In addition, extensive elevation of abdominal skin flaps creates a large wound surface predisposing to postoperative hematomas and seromas.

Components separation for ventral hernia repair requires release of the external oblique muscle lateral to the linea semilunaris and separation of the avascular plane deep to the external oblique. This allows midline advancement of the rectus abdominis in continuity with the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. As originally described, components separation requires wide undermining of the skin and subcutaneous layer to adequately expose the external oblique muscles for subsequent division. Consequently, perfusion of the undermined skin flaps can be compromised, which increases the risk of skin flap necrosis, infection, and dehiscence. In addition, extensive elevation of abdominal skin flaps creates a large wound surface predisposing to postoperative hematomas and seromas. To address this major shortcoming of conventional components separation, a modified technique of elevating partial subcutaneous flaps with preservation of the periumbilical perforating vessels arising from the inferior epigastric vessels can be performed. The rationale for using the technique of periumbilical perforator sparing (PUPS) components separation is to maximize skin blood supply. The preservation of blood flow to the midline abdominal wall should minimize complications, especially skin flap ischemia and infection. In addition, by avoiding wide undermining, subcutaneous dead space is minimized, which may reduce the incidence of seromas or hematomas. Furthermore, preservation of blood supply to the abdominal wall in ventral hernia repair allows expanded applications for patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, a recent smoking history, and for those with stomas as well as those who require concomitant panniculectomy.

To address this major shortcoming of conventional components separation, a modified technique of elevating partial subcutaneous flaps with preservation of the periumbilical perforating vessels arising from the inferior epigastric vessels can be performed. The rationale for using the technique of periumbilical perforator sparing (PUPS) components separation is to maximize skin blood supply. The preservation of blood flow to the midline abdominal wall should minimize complications, especially skin flap ischemia and infection. In addition, by avoiding wide undermining, subcutaneous dead space is minimized, which may reduce the incidence of seromas or hematomas. Furthermore, preservation of blood supply to the abdominal wall in ventral hernia repair allows expanded applications for patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, a recent smoking history, and for those with stomas as well as those who require concomitant panniculectomy.2 Innervation and Blood Supply to the Abdominal Wall Muscles

In performing all techniques of components separation abdominal wall reconstruction, it is important to understand the musculofascial anatomy, innervation, and blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall. The anterior and posterior releases in components separation allow preservation of the blood supply and innervation of the abdominal wall muscles.

In performing all techniques of components separation abdominal wall reconstruction, it is important to understand the musculofascial anatomy, innervation, and blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall. The anterior and posterior releases in components separation allow preservation of the blood supply and innervation of the abdominal wall muscles. The intercostal neurovascular bundles that contribute to the external oblique, internal oblique, transversus, and rectus muscles are preserved because they run deep to the internal oblique. They are therefore preserved during all techniques of components separation.

The intercostal neurovascular bundles that contribute to the external oblique, internal oblique, transversus, and rectus muscles are preserved because they run deep to the internal oblique. They are therefore preserved during all techniques of components separation. In addition, the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the superior epigastric vessels, which run in a longitudinal orientation deep to and within the substance of both rectus muscles, are also preserved regardless of which components separation technique is performed. Preservation of these vessels maintains the blood supply to the abdominal wall muscles.

In addition, the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the superior epigastric vessels, which run in a longitudinal orientation deep to and within the substance of both rectus muscles, are also preserved regardless of which components separation technique is performed. Preservation of these vessels maintains the blood supply to the abdominal wall muscles.3 Blood Supply to the Abdominal Wall Skin

The blood supply to the abdominal wall skin is based on direct cutaneous vessels in addition to numerous branches of deep vessels that are known as musculocutaneous perforators. Whenever abdominal wall skin is undermined, as in components separation, defining the source of vascularity to the remaining skin in critical.

The blood supply to the abdominal wall skin is based on direct cutaneous vessels in addition to numerous branches of deep vessels that are known as musculocutaneous perforators. Whenever abdominal wall skin is undermined, as in components separation, defining the source of vascularity to the remaining skin in critical. The three Huger zones of abdominal wall vascular anatomy can help guide the surgeon in planning a safe abdominal wall operation. Huger zone I, the central abdominal wall, is supplied by the deep inferior epigastric and superior epigastric vessels. Zone II, the lower abdominal wall, is supplied by the superficial inferior epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. Zone III, the lateral abdominal wall, is supplied by the intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar arteries. Skin flap elevation during conventional components separation abdominal wall reconstruction results in complete division of the cutaneous blood supply of Huger zone I, supplied by the deep epigastric vessels. The PUPS components separation approach preserves the vessels of Huger zone I, which allows improved perfusion to minimize any potential vascular related complications.

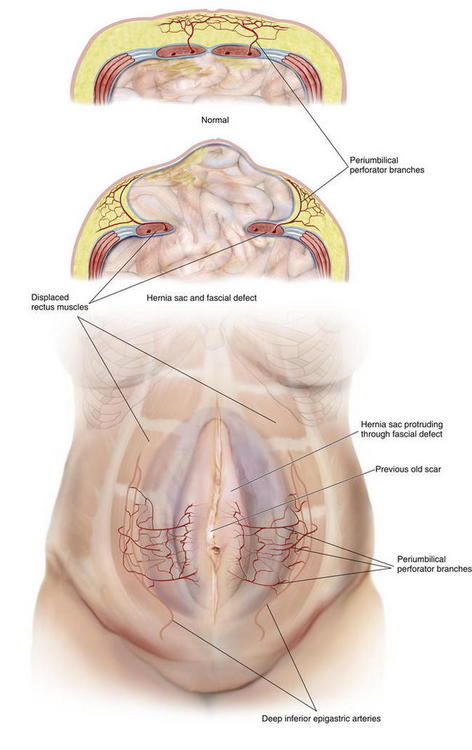

The three Huger zones of abdominal wall vascular anatomy can help guide the surgeon in planning a safe abdominal wall operation. Huger zone I, the central abdominal wall, is supplied by the deep inferior epigastric and superior epigastric vessels. Zone II, the lower abdominal wall, is supplied by the superficial inferior epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. Zone III, the lateral abdominal wall, is supplied by the intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar arteries. Skin flap elevation during conventional components separation abdominal wall reconstruction results in complete division of the cutaneous blood supply of Huger zone I, supplied by the deep epigastric vessels. The PUPS components separation approach preserves the vessels of Huger zone I, which allows improved perfusion to minimize any potential vascular related complications. The concept of vascular territories called angiosomes further elucidates our understanding of the blood supply to the abdominal wall skin. From a clinical perspective, preservation of the primary angiosome to an anatomic territory of skin maximizes blood flow to that territory. The primary central anterior abdominal wall angiosome is supplied by multiple cutaneous perforator branches of the deep epigastric artery system. Microdissection analysis of the vascular anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall skin and subcutaneous tissue has confirmed that perforator branches of the deep inferior epigastric vessels provide the main blood supply to this region. More specifically, the periumbilical region, mostly just inferior and lateral to the umbilicus is the region with the highest concentration of these perforator vessel branches (Fig. 9-1). The PUPS components separation technique focuses on maintaining this rich vascular network, thereby maximizing blood supply without compromising the degree of muscle flap advancement possible.

The concept of vascular territories called angiosomes further elucidates our understanding of the blood supply to the abdominal wall skin. From a clinical perspective, preservation of the primary angiosome to an anatomic territory of skin maximizes blood flow to that territory. The primary central anterior abdominal wall angiosome is supplied by multiple cutaneous perforator branches of the deep epigastric artery system. Microdissection analysis of the vascular anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall skin and subcutaneous tissue has confirmed that perforator branches of the deep inferior epigastric vessels provide the main blood supply to this region. More specifically, the periumbilical region, mostly just inferior and lateral to the umbilicus is the region with the highest concentration of these perforator vessel branches (Fig. 9-1). The PUPS components separation technique focuses on maintaining this rich vascular network, thereby maximizing blood supply without compromising the degree of muscle flap advancement possible.2 Preoperative Considerations

1 Optimization of Comorbidities

The primary goal in the management of the ventral hernia patient is to repair the hernia while minimizing the incidence of postoperative complications, including recurrence. As with any surgical procedure, preoperative patient optimization is vital to reducing the risk of postoperative complications. This includes smoking cessation, control of diabetes mellitus, weight loss, maximization of nutritional status, establishing an exercise routine, preoperative Staphylococcus aureus screening, and optimization of pulmonary and cardiac status.

The primary goal in the management of the ventral hernia patient is to repair the hernia while minimizing the incidence of postoperative complications, including recurrence. As with any surgical procedure, preoperative patient optimization is vital to reducing the risk of postoperative complications. This includes smoking cessation, control of diabetes mellitus, weight loss, maximization of nutritional status, establishing an exercise routine, preoperative Staphylococcus aureus screening, and optimization of pulmonary and cardiac status.2 Defining the Defect and Patient Anatomy

Preoperative Physical Examination

Preoperative Physical Examination

A focused preoperative physical examination is very important in planning the operative approach in abdominal wall reconstruction and helps identify the appropriate candidate for PUPS components separation. Components separation procedures are useful for midline and paramedian hernias in which the fascia cannot be approximated without flap release and advancement. In general, components separation can allow fascial approximation for most midline defects smaller than 20 cm at the waistline.

A focused preoperative physical examination is very important in planning the operative approach in abdominal wall reconstruction and helps identify the appropriate candidate for PUPS components separation. Components separation procedures are useful for midline and paramedian hernias in which the fascia cannot be approximated without flap release and advancement. In general, components separation can allow fascial approximation for most midline defects smaller than 20 cm at the waistline. The size of the defect and loss of domain can be estimated by physical examination. The combination of a large hernia sac and a large hernia defect are the typical findings on exam that may predict the need for a components separation. A large sac with a small defect frequently does not require a components separation procedure to obtain fascial closure, whereas a large defect with a small sac may. However, there is no exact size of defect that predicts the need for a components separation procedure because abdominal wall compliance varies from patient to patient.

The size of the defect and loss of domain can be estimated by physical examination. The combination of a large hernia sac and a large hernia defect are the typical findings on exam that may predict the need for a components separation. A large sac with a small defect frequently does not require a components separation procedure to obtain fascial closure, whereas a large defect with a small sac may. However, there is no exact size of defect that predicts the need for a components separation procedure because abdominal wall compliance varies from patient to patient. Preoperative Abdominal CT Scan

Preoperative Abdominal CT Scan

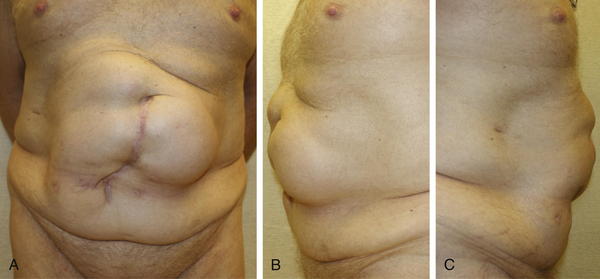

Preoperative imaging studies also are useful in planning the operative procedure. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan provides an accurate measurement of the size of the ventral hernia defect and can demonstrate the size and contents of the hernia sac (Fig. 9- 2). This information can help predict the need for a components separation procedure. A CT scan also may reveal the presence of any other hernia defects or other pathology otherwise not appreciated on physical examination. Other hernia defects potentially identified on a CT scan can then be addressed at the time of abdominal wall reconstruction.

Preoperative imaging studies also are useful in planning the operative procedure. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan provides an accurate measurement of the size of the ventral hernia defect and can demonstrate the size and contents of the hernia sac (Fig. 9- 2). This information can help predict the need for a components separation procedure. A CT scan also may reveal the presence of any other hernia defects or other pathology otherwise not appreciated on physical examination. Other hernia defects potentially identified on a CT scan can then be addressed at the time of abdominal wall reconstruction. In patients who have had a prior wide subcutaneous flap procedure or other abdominal surgery where the periumbilical perforator blood supply to the abdominal wall may have been divided, a CT angiogram can be performed. CT angiography can identify the remaining blood supply to the central abdominal wall in order to help operative planning. The location of intact perforators can be identified preoperatively and thereby preserved during PUPS components separation.

In patients who have had a prior wide subcutaneous flap procedure or other abdominal surgery where the periumbilical perforator blood supply to the abdominal wall may have been divided, a CT angiogram can be performed. CT angiography can identify the remaining blood supply to the central abdominal wall in order to help operative planning. The location of intact perforators can be identified preoperatively and thereby preserved during PUPS components separation.3 Choosing the Type of Components Separation

The technique of PUPS can be performed in essentially any patient thought to be a candidate for components separation.

The technique of PUPS can be performed in essentially any patient thought to be a candidate for components separation. In all cases, the choice is made between two categories of components separation procedures: those that preserve the periumbilical perforators and those that do not. While this choice can be made preoperatively, the final selection of procedure may rely on findings at the time of surgery.

In all cases, the choice is made between two categories of components separation procedures: those that preserve the periumbilical perforators and those that do not. While this choice can be made preoperatively, the final selection of procedure may rely on findings at the time of surgery. The conventional components separation (as described in Chapter 8) requires significant skin undermining and division of the periumbilical perforators and should be performed only if extensive subcutaneous skin flap elevation is necessary (i.e., as done during removal of an infected onlay synthetic mesh). Otherwise a periumbilical perforator sparing technique, performed open or laparoscopic should be attempted in all cases requiring components separation.

The conventional components separation (as described in Chapter 8) requires significant skin undermining and division of the periumbilical perforators and should be performed only if extensive subcutaneous skin flap elevation is necessary (i.e., as done during removal of an infected onlay synthetic mesh). Otherwise a periumbilical perforator sparing technique, performed open or laparoscopic should be attempted in all cases requiring components separation. Procedures that preserve the periumbilical perforators include the open PUPS components separation and the laparoscopic components separation procedures.

Procedures that preserve the periumbilical perforators include the open PUPS components separation and the laparoscopic components separation procedures. If dissection and removal of the hernia sac results in partial subcutaneous flap creation then one should continue that dissection around the periumbilical perforators and perform an open PUPS components separation. If there is no skin flap creation during removal of the hernia sac then a laparoscopic components separation can be performed (as described in Chapter 11).

If dissection and removal of the hernia sac results in partial subcutaneous flap creation then one should continue that dissection around the periumbilical perforators and perform an open PUPS components separation. If there is no skin flap creation during removal of the hernia sac then a laparoscopic components separation can be performed (as described in Chapter 11). One of the limitations of the laparoscopic components separation technique is that it may not always provide the same degree of fascial release as compared to conventional components separation. In our experience, the extent of fascial release provided by open PUPS components separation is equivalent to the degree of release possible with the conventional open approach.

One of the limitations of the laparoscopic components separation technique is that it may not always provide the same degree of fascial release as compared to conventional components separation. In our experience, the extent of fascial release provided by open PUPS components separation is equivalent to the degree of release possible with the conventional open approach.4 Choosing the Type of Mesh

Mesh placement is strongly advised once the PUPS components separation procedure is completed in order to minimize post operative hernia recurrence.

Mesh placement is strongly advised once the PUPS components separation procedure is completed in order to minimize post operative hernia recurrence. In the patient with multiple comorbidities, who is at higher risk for developing a postoperative surgical site infection, the implantation of a biologic matrix to reinforce fascial closure after components separation may be more appropriate than a synthetic mesh. Similarly, if the patient has a clean-contaminated or contaminated wound, then a biologic matrix should be implanted. A patient with minimal or no comorbidities and a clean operative wound class can have a synthetic mesh implanted for fascial reinforcement. If the wound is too contaminated or dirty, then mesh implantation should be avoided and a staged repair with mesh implantation at a later date should be considered.

In the patient with multiple comorbidities, who is at higher risk for developing a postoperative surgical site infection, the implantation of a biologic matrix to reinforce fascial closure after components separation may be more appropriate than a synthetic mesh. Similarly, if the patient has a clean-contaminated or contaminated wound, then a biologic matrix should be implanted. A patient with minimal or no comorbidities and a clean operative wound class can have a synthetic mesh implanted for fascial reinforcement. If the wound is too contaminated or dirty, then mesh implantation should be avoided and a staged repair with mesh implantation at a later date should be considered.3 Operative Steps

2 Preoperative Markings (Fig. 9-4)

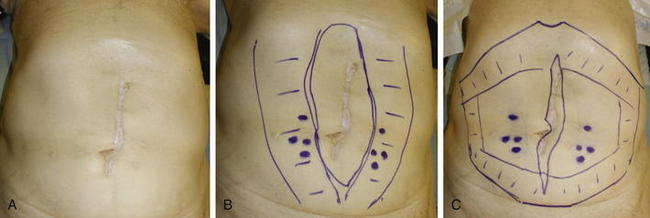

Before surgery, the patient’s abdominal wall is marked. The hernia defect is outlined, and the locations of the periumbilical perforators are marked in reference to the rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 9-4, B). The perforators are usually located within a 6 cm radius of the umbilicus but can be more laterally positioned in the presence of a large hernia sac.

Before surgery, the patient’s abdominal wall is marked. The hernia defect is outlined, and the locations of the periumbilical perforators are marked in reference to the rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 9-4, B). The perforators are usually located within a 6 cm radius of the umbilicus but can be more laterally positioned in the presence of a large hernia sac. The planned subcutaneous tunnels along each costal margin and each inguinal region are drawn on the abdomen.

The planned subcutaneous tunnels along each costal margin and each inguinal region are drawn on the abdomen.4 Exposure

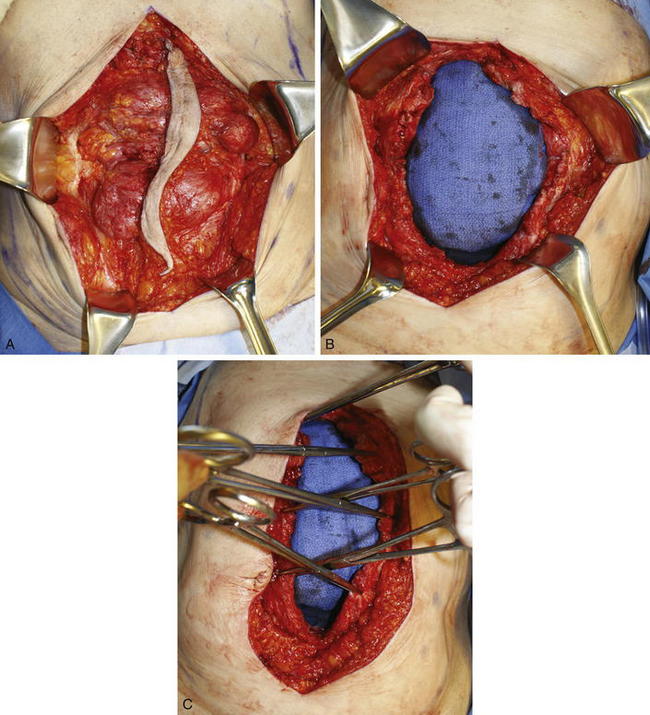

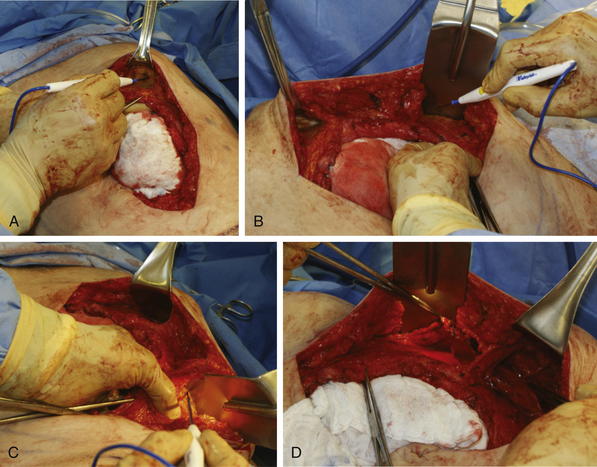

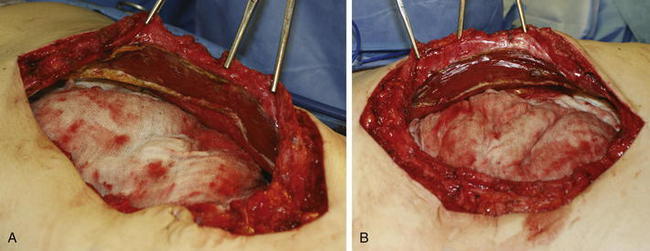

The old scar and subcutaneous tissue posterior to the scar is excised. This is performed usually en bloc with the ventral hernia sac (Fig. 9-5, A). Care is taken during dissection of the ventral hernia sac not to undermine too widely from the sac in order to avoid injury to the periumbilical perforators. Once the dissection is completed to the edge of the fascial defect, the hernia sac is opened and excised (Fig. 9-5, B).

The old scar and subcutaneous tissue posterior to the scar is excised. This is performed usually en bloc with the ventral hernia sac (Fig. 9-5, A). Care is taken during dissection of the ventral hernia sac not to undermine too widely from the sac in order to avoid injury to the periumbilical perforators. Once the dissection is completed to the edge of the fascial defect, the hernia sac is opened and excised (Fig. 9-5, B).5 Adhesiolysis

Any adhesions to the hernia sac and posterior abdominal wall must be fully lysed. If the patient has a history of adhesive small bowel obstruction, then all intraabdominal adhesions are lysed and consideration is given to placement of an antiadhesion material. Any concommitant intraabdominal procedure is performed at this time if necessary.

Any adhesions to the hernia sac and posterior abdominal wall must be fully lysed. If the patient has a history of adhesive small bowel obstruction, then all intraabdominal adhesions are lysed and consideration is given to placement of an antiadhesion material. Any concommitant intraabdominal procedure is performed at this time if necessary.6 Assessment of Fascial Approximation and Tension

Assessment of fascial approximation is performed by placement of two or three Kocher clamps on each medial fascial edge (Fig. 9-5, C). If the fasciae can be easily approximated with minimal or physiologic tension then a components separation is not required. If the fascial edges do not approximate easily, then a components separation should be performed.

Assessment of fascial approximation is performed by placement of two or three Kocher clamps on each medial fascial edge (Fig. 9-5, C). If the fasciae can be easily approximated with minimal or physiologic tension then a components separation is not required. If the fascial edges do not approximate easily, then a components separation should be performed.7 Creation of Subcutaneous Tunnels

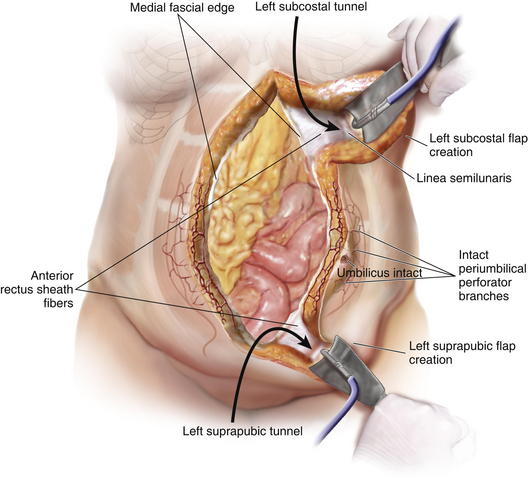

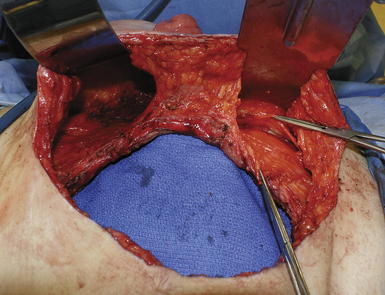

The PUPS components separation is now begun with creation of subcutaneous tunnels that will allow exposure of the anterior aspect of the external oblique fascia bilaterally (Fig. 9-6 and Fig. 9-7).

The PUPS components separation is now begun with creation of subcutaneous tunnels that will allow exposure of the anterior aspect of the external oblique fascia bilaterally (Fig. 9-6 and Fig. 9-7). At the epigastric and suprapubic levels, using fiber optic lighted retraction, the skin and subcutaneous tissues are dissected off the anterior rectus sheath extending just lateral to the linea semilunaris. The epigastric tunnel typically exposes the costal margin and extends inferiorly from the xiphoid to a level 2 to 4 cm superior to the umbilicus (Fig. 9-8, A). The suprapubic tunnel typically exposes the inguinal ligament and extends superiorly from the pubic tubercle to a level 6 to 8 cm inferior to the umbilicus (Fig. 9-8, B).

At the epigastric and suprapubic levels, using fiber optic lighted retraction, the skin and subcutaneous tissues are dissected off the anterior rectus sheath extending just lateral to the linea semilunaris. The epigastric tunnel typically exposes the costal margin and extends inferiorly from the xiphoid to a level 2 to 4 cm superior to the umbilicus (Fig. 9-8, A). The suprapubic tunnel typically exposes the inguinal ligament and extends superiorly from the pubic tubercle to a level 6 to 8 cm inferior to the umbilicus (Fig. 9-8, B).8 Connecting the Subcutaneous Tunnels

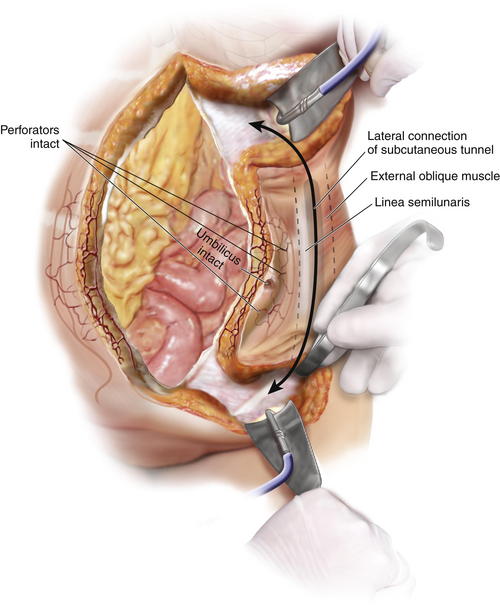

The epigastric and suprapubic subcutaneous tunnels can be connected before or during the division of the external oblique muscle.

The epigastric and suprapubic subcutaneous tunnels can be connected before or during the division of the external oblique muscle. Using a deep fiber optic lighted retractor or a headlight and deep Deaver retractor, these tunnels are connected from the top down and from the bottom up using cautery dissection. In this way, they can be joined together lateral to the linea semilunaris while avoiding injury to the periumbilical perforators (Fig. 9-8, C).

Using a deep fiber optic lighted retractor or a headlight and deep Deaver retractor, these tunnels are connected from the top down and from the bottom up using cautery dissection. In this way, they can be joined together lateral to the linea semilunaris while avoiding injury to the periumbilical perforators (Fig. 9-8, C).9 Division of the Aponeurosis of the External Oblique Muscle

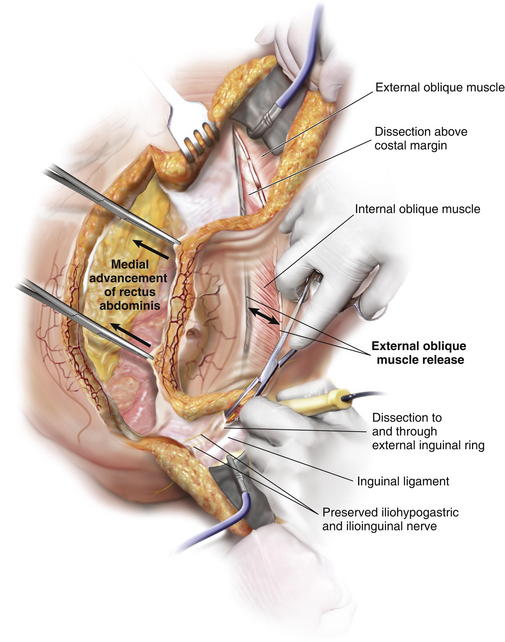

Exposure for division of the external oblique muscle fascia is through the epigastric and suprapubic tunnels. The rectus abdominis can be manually retracted medially and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is divided with cautery in a longitudinal orientation approximately 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris (Fig. 9-8, C) (Fig. 9-9). Note that at this distance from the linea semilunaris, the external oblique is comprised of thin fascia inferiorly and thicker muscle superiorly.

Exposure for division of the external oblique muscle fascia is through the epigastric and suprapubic tunnels. The rectus abdominis can be manually retracted medially and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is divided with cautery in a longitudinal orientation approximately 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris (Fig. 9-8, C) (Fig. 9-9). Note that at this distance from the linea semilunaris, the external oblique is comprised of thin fascia inferiorly and thicker muscle superiorly. The external oblique division can continue superiorly approximately 5 to 6 cm over the costal margin onto the thoracic ribcage and can extend inferiorly to the external inguinal ring if necessary (Fig. 9-9). Fiber optic lighted retraction allows maintenance of an optical cavity lateral to the linea semilunaris such that the periumbilical perforators are preserved during fascial incision.

The external oblique division can continue superiorly approximately 5 to 6 cm over the costal margin onto the thoracic ribcage and can extend inferiorly to the external inguinal ring if necessary (Fig. 9-9). Fiber optic lighted retraction allows maintenance of an optical cavity lateral to the linea semilunaris such that the periumbilical perforators are preserved during fascial incision. Once the external oblique muscle is completely divided, it is then separated from the underlying internal oblique muscle in an avascular plane laterally toward the flank (Fig. 9-8, D).

Once the external oblique muscle is completely divided, it is then separated from the underlying internal oblique muscle in an avascular plane laterally toward the flank (Fig. 9-8, D).10 Reassessment of Fascial Approximation

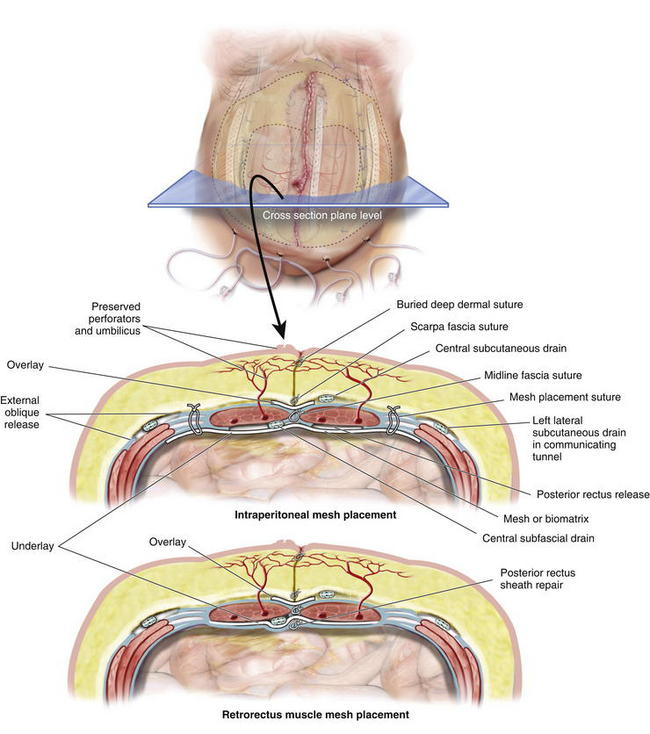

Once the external oblique PUPS components separation release has been performed bilaterally, midline fascial approximation is reattempted. If successful, then mesh implantation can be performed. If unsuccessful, a posterior rectus release can be performed to increase the amount of rectus abdominis muscle advancement medially.

Once the external oblique PUPS components separation release has been performed bilaterally, midline fascial approximation is reattempted. If successful, then mesh implantation can be performed. If unsuccessful, a posterior rectus release can be performed to increase the amount of rectus abdominis muscle advancement medially.11 Division of Posterior Rectus Fascia

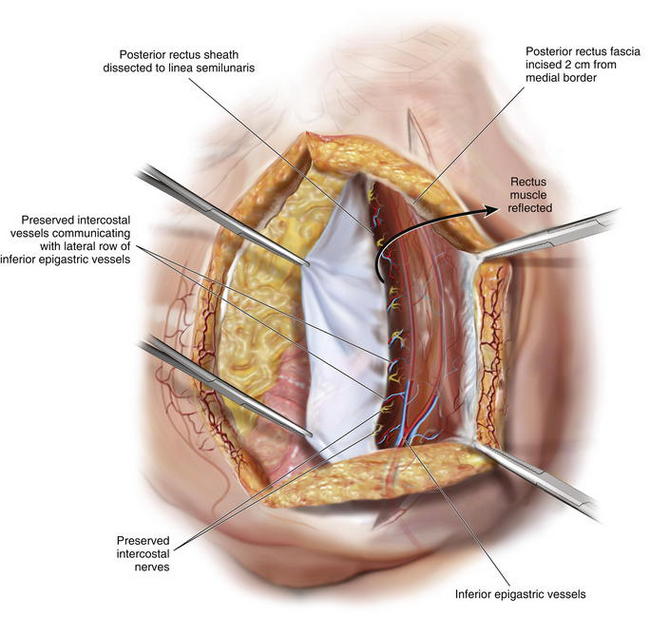

If the posterior release is needed, the medial rectus abdominis edge can be retracted anteriorly and laterally with Kocher clamps, and the posterior rectus sheath can be incised longitudinally with cautery approximately 2 cm from the midline. From superior to inferior, this release can extend from under the costal margin to the arcuate line of Douglas where the posterior rectus sheath terminates (Figs. 9-10 and 9-11). Division of the posterior rectus sheath in this fashion typically yields another 1to 2 cm of release per side. Fascial approximation at the midline is again assessed.

If the posterior release is needed, the medial rectus abdominis edge can be retracted anteriorly and laterally with Kocher clamps, and the posterior rectus sheath can be incised longitudinally with cautery approximately 2 cm from the midline. From superior to inferior, this release can extend from under the costal margin to the arcuate line of Douglas where the posterior rectus sheath terminates (Figs. 9-10 and 9-11). Division of the posterior rectus sheath in this fashion typically yields another 1to 2 cm of release per side. Fascial approximation at the midline is again assessed.12 Mesh Placement

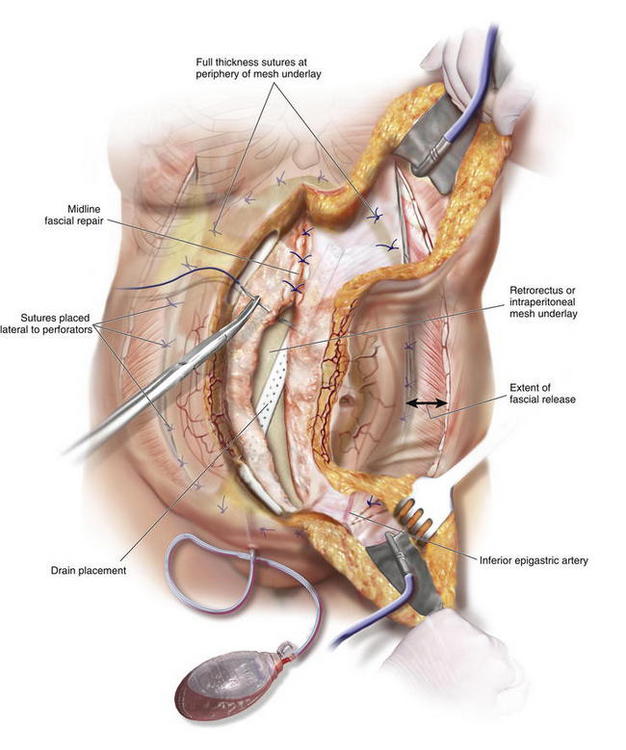

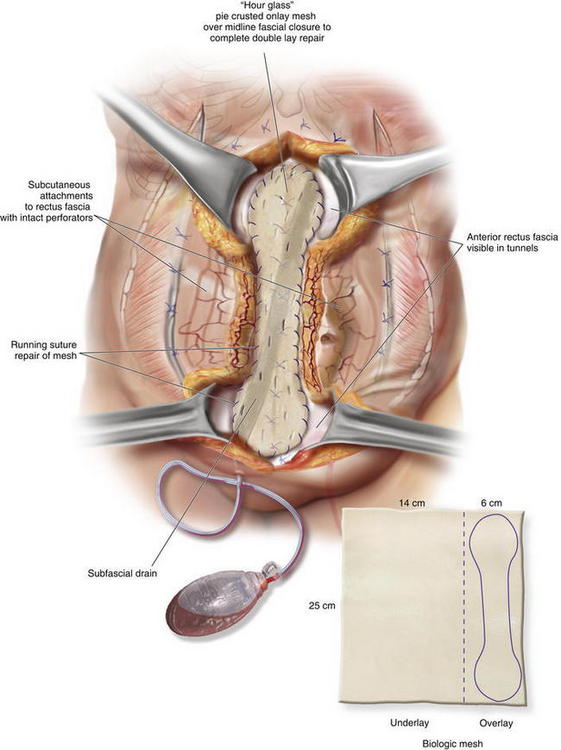

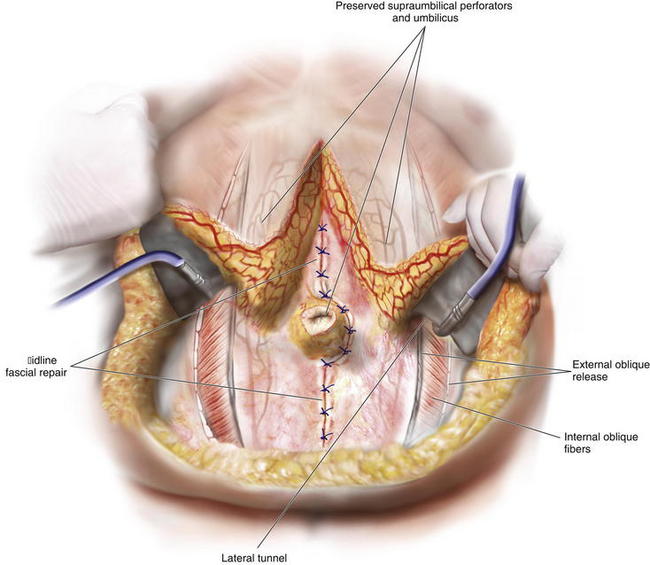

Once the PUPS components separation has been completed, mesh placement is performed. The mesh is typically placed as an underlay in a retro-rectus or intraperitoneal location, whether a synthetic mesh or a biologic matrix is chosen, because the periumbilical perforators have been preserved (Fig. 9-12).

Once the PUPS components separation has been completed, mesh placement is performed. The mesh is typically placed as an underlay in a retro-rectus or intraperitoneal location, whether a synthetic mesh or a biologic matrix is chosen, because the periumbilical perforators have been preserved (Fig. 9-12). In placing the mesh as an underlay, the subcutaneous tunnels are used for placement of horizontal mattress transfascial sutures laterally to secure the mesh, thereby avoiding the periumbilical perforator vessels. The lateral sutures can be passed through the laterally displaced cut edge of the external oblique if the mesh underlay is wide enough. Otherwise, sutures can be placed through the medial cut edge of the external oblique at the linea semilunaris just lateral to the perforators (as noted in Fig 9-13 and 9-14). However, placement of sutures through the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles in the lateral subcutaneous tunnel can be performed to secure the underlay mesh as well. The mesh can be sutured with permanent or long-lasting absorbable sutures.

In placing the mesh as an underlay, the subcutaneous tunnels are used for placement of horizontal mattress transfascial sutures laterally to secure the mesh, thereby avoiding the periumbilical perforator vessels. The lateral sutures can be passed through the laterally displaced cut edge of the external oblique if the mesh underlay is wide enough. Otherwise, sutures can be placed through the medial cut edge of the external oblique at the linea semilunaris just lateral to the perforators (as noted in Fig 9-13 and 9-14). However, placement of sutures through the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles in the lateral subcutaneous tunnel can be performed to secure the underlay mesh as well. The mesh can be sutured with permanent or long-lasting absorbable sutures. Before fascial closure, a drain should be placed anterior to the mesh to minimize the incidence of subfascial fluid accumulation (see Figs. 9-12 and 9-13, A). This fluid could otherwise be a source of postoperative discomfort or infection, and it can be a barrier preventing apposition of the mesh to the rectus muscle, thereby preventing early fibroblast and vascular ingrowth and incorporation.

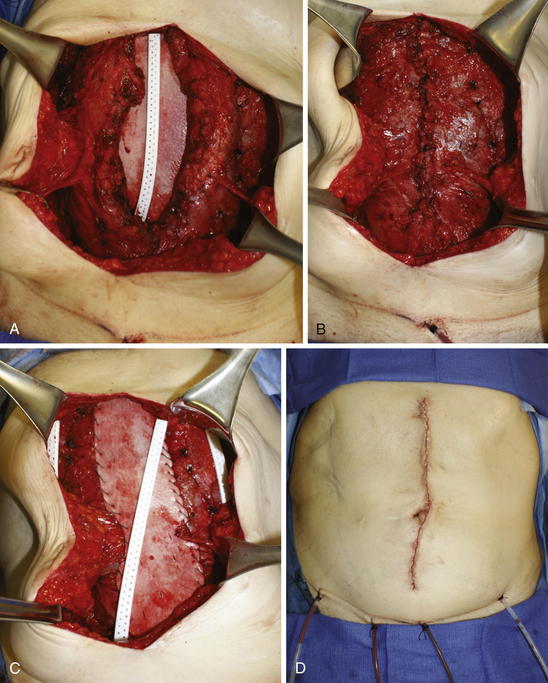

Before fascial closure, a drain should be placed anterior to the mesh to minimize the incidence of subfascial fluid accumulation (see Figs. 9-12 and 9-13, A). This fluid could otherwise be a source of postoperative discomfort or infection, and it can be a barrier preventing apposition of the mesh to the rectus muscle, thereby preventing early fibroblast and vascular ingrowth and incorporation. A “double lay” mesh placement, combining both an underlay and onlay mesh, can be performed in cases of biologic matrix implantation in an attempt to minimize the chance of hernia recurrence (Fig. 9-14). A 4- to 6-cm wide segment of mesh is cut from the lateral side of the original piece. The underlay component is sutured in with at least a 5- to 7-cm underlayment; a drain is placed anterior to the underlay mesh, and the fascia is closed primarily over the drain. The onlay mesh piece is “pie-crusted” before implantation to avoid seroma entrapment between the anterior rectus sheath and the onlay mesh. The onlay portion of the double lay matrix may need to be “hour-glassed” at the level of the periumbilical perforators in order to preserve them. The onlay mesh can be sutured along its perimeter with a running long-lasting absorbable or permanent suture.

A “double lay” mesh placement, combining both an underlay and onlay mesh, can be performed in cases of biologic matrix implantation in an attempt to minimize the chance of hernia recurrence (Fig. 9-14). A 4- to 6-cm wide segment of mesh is cut from the lateral side of the original piece. The underlay component is sutured in with at least a 5- to 7-cm underlayment; a drain is placed anterior to the underlay mesh, and the fascia is closed primarily over the drain. The onlay mesh piece is “pie-crusted” before implantation to avoid seroma entrapment between the anterior rectus sheath and the onlay mesh. The onlay portion of the double lay matrix may need to be “hour-glassed” at the level of the periumbilical perforators in order to preserve them. The onlay mesh can be sutured along its perimeter with a running long-lasting absorbable or permanent suture.13 Midline Fascial Closure

Midline fascial closure is performed following completion of the underlay mesh placement (see Fig. 9-13, B). If the fasciae approximate with some tension, an interrupted figure of eight closure is used. This can be performed from the top down and from the bottom up until the point of maximal tension is closed. If the fascial edges approximate easily, a running closure can be performed.

Midline fascial closure is performed following completion of the underlay mesh placement (see Fig. 9-13, B). If the fasciae approximate with some tension, an interrupted figure of eight closure is used. This can be performed from the top down and from the bottom up until the point of maximal tension is closed. If the fascial edges approximate easily, a running closure can be performed.14 Onlay Mesh Placement

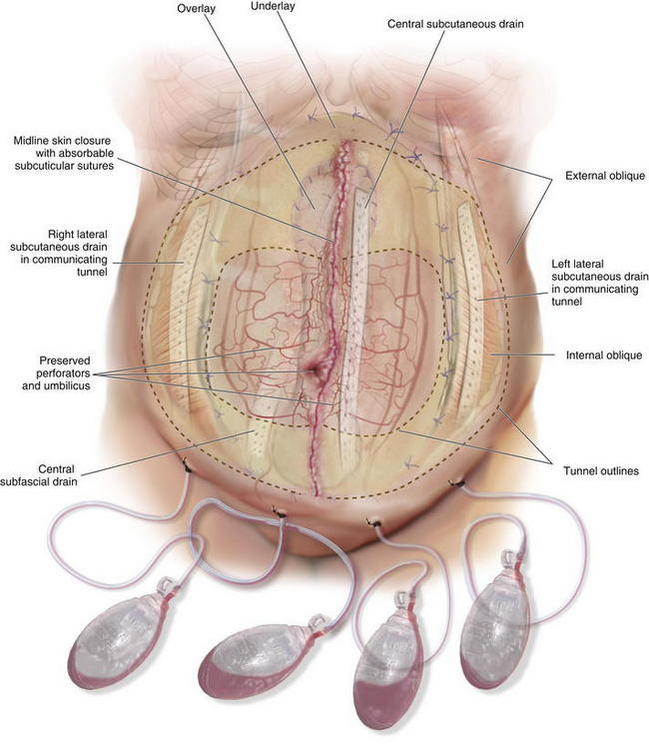

15 Subcutaneous Drain Placement

There are three subcutaneous compartments following a PUPS components separation. There is a right lateral, a left lateral, and a central abdominal subcutaneous compartment. Each of these compartments should have a subcutaneous drain. Therefore, each patient would have three subcutaneous drains and one subfascial drain (Fig. 9-15).

There are three subcutaneous compartments following a PUPS components separation. There is a right lateral, a left lateral, and a central abdominal subcutaneous compartment. Each of these compartments should have a subcutaneous drain. Therefore, each patient would have three subcutaneous drains and one subfascial drain (Fig. 9-15).16 Skin Closure

The subcutaneous tunnels are closed with absorbable quilting sutures between the deep subcutaneous tissue and the anterior rectus abdominis fascia. This is done to reduce dead space and minimize the risk of seroma formation.

The subcutaneous tunnels are closed with absorbable quilting sutures between the deep subcutaneous tissue and the anterior rectus abdominis fascia. This is done to reduce dead space and minimize the risk of seroma formation. Midline abdominal wall closure includes the placement of interrupted absorbable sutures for approximation of Scarpa fascia, as well as a deep dermal repair. The skin closure can be performed with staples or with absorbable subcuticular sutures covered by a liquid epidermal bonding agent (Fig. 9-13, D and Fig. 9-16).

Midline abdominal wall closure includes the placement of interrupted absorbable sutures for approximation of Scarpa fascia, as well as a deep dermal repair. The skin closure can be performed with staples or with absorbable subcuticular sutures covered by a liquid epidermal bonding agent (Fig. 9-13, D and Fig. 9-16).4 Postoperative Care

Perioperative antibiotics are given as one dose preoperatively and up to 24 hours postoperatively unless the patient has a documented active infection. If the patient has an active infection, antibiotics are given until the infection is cleared.

Perioperative antibiotics are given as one dose preoperatively and up to 24 hours postoperatively unless the patient has a documented active infection. If the patient has an active infection, antibiotics are given until the infection is cleared. Most of the patients who require abdominal wall reconstruction are at higher risk for development of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary emboli. Therefore a dose of subcutaneous heparin is given before induction of anesthesia and is continued postoperatively until the patient is freely ambulating. Compression stockings also are used for DVT prophylaxis until the patient is ambulatory.

Most of the patients who require abdominal wall reconstruction are at higher risk for development of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary emboli. Therefore a dose of subcutaneous heparin is given before induction of anesthesia and is continued postoperatively until the patient is freely ambulating. Compression stockings also are used for DVT prophylaxis until the patient is ambulatory. Postoperative pain control is achieved with the epidural catheter. If an epidural catheter cannot be used, then an intravenous patient controlled analgesia system is used for postoperative pain management.

Postoperative pain control is achieved with the epidural catheter. If an epidural catheter cannot be used, then an intravenous patient controlled analgesia system is used for postoperative pain management. The subfascial drain usually stops draining in the first week postoperatively and is removed before discharge from the hospital. The other drains are left in place until the output is less than 20 to 30 mL per day for 2 consecutive days. If a double lay placement of the mesh was performed, it is not uncommon for the central compartment subcutaneous drain to stay in for 3 to 6 weeks postoperatively.

The subfascial drain usually stops draining in the first week postoperatively and is removed before discharge from the hospital. The other drains are left in place until the output is less than 20 to 30 mL per day for 2 consecutive days. If a double lay placement of the mesh was performed, it is not uncommon for the central compartment subcutaneous drain to stay in for 3 to 6 weeks postoperatively.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

1 Managing the Reoperative Patient

Patients with Previous Ventral Hernia Repair

Patients with Previous Ventral Hernia Repair

Many patients who require a components separation operation have already undergone prior ventral hernia repair. Skin flaps may have been created and the periumbilical perforators may have already been divided.

Many patients who require a components separation operation have already undergone prior ventral hernia repair. Skin flaps may have been created and the periumbilical perforators may have already been divided. In such patients, a CT angiogram can be useful in establishing the presence or absence of periumbilical perforators and thereby determining if a PUPS procedure is warranted. The CT angiogram also may identify collateral blood flow to the abdominal wall such as prominent superficial inferior epigastric vessels, which should then be preserved to ensure vascular supply to the skin.

In such patients, a CT angiogram can be useful in establishing the presence or absence of periumbilical perforators and thereby determining if a PUPS procedure is warranted. The CT angiogram also may identify collateral blood flow to the abdominal wall such as prominent superficial inferior epigastric vessels, which should then be preserved to ensure vascular supply to the skin. Prior Surgical Scars

Prior Surgical Scars

During the preoperative evaluation, it is critical to note all healed surgical scars, including old laparoscopic trocar site scars. This is because release of the external oblique muscle during components separation across a healed fascial incision may leave weakened or attenuated internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle fasciae. This will result in a significant risk for the development of a lateral postoperative hernia at that site.

During the preoperative evaluation, it is critical to note all healed surgical scars, including old laparoscopic trocar site scars. This is because release of the external oblique muscle during components separation across a healed fascial incision may leave weakened or attenuated internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle fasciae. This will result in a significant risk for the development of a lateral postoperative hernia at that site. Management of Stomas and Stoma Sites

Management of Stomas and Stoma Sites

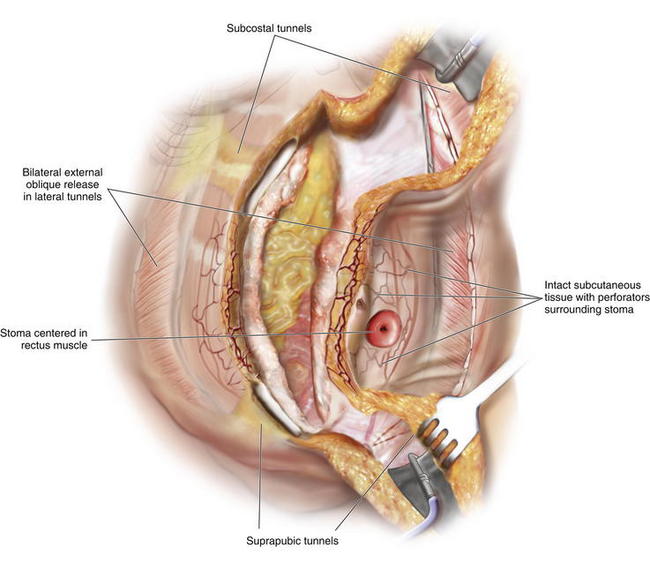

Stomas, when properly constructed, pass through the rectus abdominis muscle and are not a contraindication for PUPS components separation. A stoma that passes through the rectus abdominis muscle does not interfere with division of the external oblique muscle fascia. When completing a PUPS components separation procedure, the entire area of subcutaneous tissue surrounding the stoma, or surrounding the site of a stoma reversal, is preserved, and the external oblique muscle can be easily divided laterally while still preserving the periumbilical perforators (Figs. 9-17 and 9-18). This allows PUPS components separation to be safely accomplished simultaneously with a stoma reversal operation. The site of the old stoma remains completely separate from any area of skin undermining.

Stomas, when properly constructed, pass through the rectus abdominis muscle and are not a contraindication for PUPS components separation. A stoma that passes through the rectus abdominis muscle does not interfere with division of the external oblique muscle fascia. When completing a PUPS components separation procedure, the entire area of subcutaneous tissue surrounding the stoma, or surrounding the site of a stoma reversal, is preserved, and the external oblique muscle can be easily divided laterally while still preserving the periumbilical perforators (Figs. 9-17 and 9-18). This allows PUPS components separation to be safely accomplished simultaneously with a stoma reversal operation. The site of the old stoma remains completely separate from any area of skin undermining.2 Proper Identification of the External Oblique Fascia

If the rectus abdominis muscle is wide or displaced laterally, identification of the external oblique fascia lateral to the linea semilunaris may require added attention. Confirmation of proper identification of the external oblique fascia can be done with gentle cautery. If cautery stimulation causes the underlying muscle to twitch in a longitudinal orientation, consistent with the rectus abdominis muscle contracting, a more lateral exposure is required. When cautery stimulation reveals muscle twitching in an oblique orientation, identification of the external oblique fascia is confirmed.

If the rectus abdominis muscle is wide or displaced laterally, identification of the external oblique fascia lateral to the linea semilunaris may require added attention. Confirmation of proper identification of the external oblique fascia can be done with gentle cautery. If cautery stimulation causes the underlying muscle to twitch in a longitudinal orientation, consistent with the rectus abdominis muscle contracting, a more lateral exposure is required. When cautery stimulation reveals muscle twitching in an oblique orientation, identification of the external oblique fascia is confirmed. Once the external oblique fascia is incised longitudinally, the cut fascial edge can be elevated to identify the underlying internal oblique with its muscle fibers directed inferolaterally and the underside of the external oblique muscle with its fibers directed superolaterally. If longitudinally oriented muscle fibers are seen after fascial division (rectus abdominis muscle), the exposure is likely medial to the linea semilunaris. In this case, the anterior fascia should be repaired and dissection should extend more laterally.

Once the external oblique fascia is incised longitudinally, the cut fascial edge can be elevated to identify the underlying internal oblique with its muscle fibers directed inferolaterally and the underside of the external oblique muscle with its fibers directed superolaterally. If longitudinally oriented muscle fibers are seen after fascial division (rectus abdominis muscle), the exposure is likely medial to the linea semilunaris. In this case, the anterior fascia should be repaired and dissection should extend more laterally.3 Maximizing Midline Fascial Advancement

Midline flap advancement can sometimes be limited by the ribs at the epigastric region. In order to maximize advancement at this level, the longitudinal external oblique muscle release incision can extend superiorly 5 to 6 cm over the ribs.

Midline flap advancement can sometimes be limited by the ribs at the epigastric region. In order to maximize advancement at this level, the longitudinal external oblique muscle release incision can extend superiorly 5 to 6 cm over the ribs. Even further release at this level can be gained by incising the anterior rectus fascia transversely, extending medially from the superior limit of the external oblique incision.

Even further release at this level can be gained by incising the anterior rectus fascia transversely, extending medially from the superior limit of the external oblique incision. In cases in which fascial reapproximation was not possible despite an external oblique and posterior rectus release. The medial side of the cut posterior rectus sheath can be flipped medially to help achieve midline fascial closure. The integrity of this closure can be suboptimal; therefore, a double lay mesh placement is ideal in providing additional fascial support in this setting.

In cases in which fascial reapproximation was not possible despite an external oblique and posterior rectus release. The medial side of the cut posterior rectus sheath can be flipped medially to help achieve midline fascial closure. The integrity of this closure can be suboptimal; therefore, a double lay mesh placement is ideal in providing additional fascial support in this setting.5 Panniculectomy

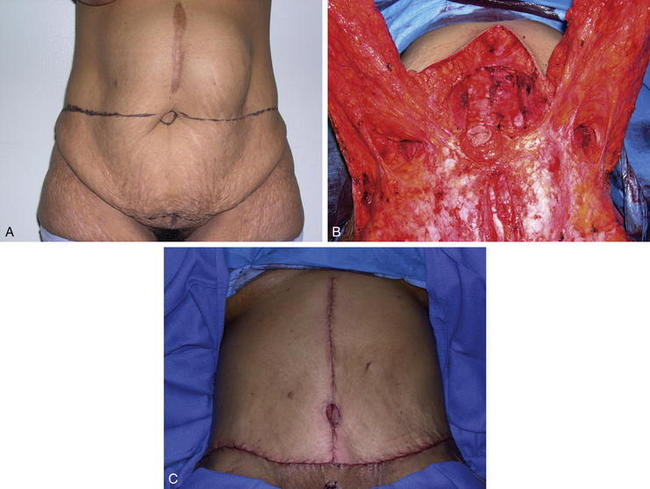

Patients with obesity or with a history of massive weight loss may benefit from simultaneous panniculectomy in the setting of ventral incisional hernia repair (Fig. 9-19, A).

Patients with obesity or with a history of massive weight loss may benefit from simultaneous panniculectomy in the setting of ventral incisional hernia repair (Fig. 9-19, A). The transverse excision of infraumbilical skin and subcutaneous tissue in a panniculectomy results in division of the superficial inferior epigastric blood vessels. As such, when doing a components separation procedure simultaneously with a panniculectomy, preservation of the periumbilical perforator blood supply to the upper abdominal wall skin is critical in order to avoid skin ischemia and wound healing problems.

The transverse excision of infraumbilical skin and subcutaneous tissue in a panniculectomy results in division of the superficial inferior epigastric blood vessels. As such, when doing a components separation procedure simultaneously with a panniculectomy, preservation of the periumbilical perforator blood supply to the upper abdominal wall skin is critical in order to avoid skin ischemia and wound healing problems. The PUPS approach to components separation allows safe simultaneous panniculectomy. The hernia defect is approached through the previous midline incision. The external oblique fascial incision lateral to the linea semilunaris can then be approached through a longitudinal subcutaneous tunnel created following the panniculectomy (Figs. 9-19, B and 9-20). With fiber optic lighted retraction, dissection with incision of the external obliques can extend several centimeters superior to the costal margin through this approach.

The PUPS approach to components separation allows safe simultaneous panniculectomy. The hernia defect is approached through the previous midline incision. The external oblique fascial incision lateral to the linea semilunaris can then be approached through a longitudinal subcutaneous tunnel created following the panniculectomy (Figs. 9-19, B and 9-20). With fiber optic lighted retraction, dissection with incision of the external obliques can extend several centimeters superior to the costal margin through this approach.Agnew S.P., Small W.Jr., Wang E., Smith L.J., Hadad I., Dumanian G.A. Prospective measurements of intra-abdominal volume and pulmonary function after repair of massive ventral hernias with the components separation technique. Ann Surg. 2010;25(5):981-988.

Ceydeli A., Rucinski J., Wise L. Finding the best abdominal closure: An evidence based review of the literature. Curr Surg. 2005;62:220-225.

Dunne J.R., Malone D.L., Tracy J.K., Napolitano L.M. Abdominal wall hernias: risk factors for infection and resource utilization. J Surg Res. 2003;111:78-84.

El-Mrakby H.H., Milner R.H. The vascular anatomy of the lower anterior abdominal wall: a microdissection study on the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the perforator branches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(2):539-543. discussion 544-7

Finan K.R., Vick C.C., Kiefe C.L., Neumayer L., Hawn M.T. Predictors of wound infection in ventral hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2005;190:676-681.

Huger W.E.Jr. The anatomical rationale for abdominal lipectomy. Am Surg. 1979;45:612.

Ramirez O.M., Ruas E., Dellon L. Component separation method for closure of abdominal wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:519-526.

Kolker A.R., Brown D.J., Redstone J.S., Scarpinato V.M., Wallack M.K. Multilayer reconstruction of abdominal wall defects with acellular dermal allograft and component separation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:36-42.

Reid R.R., Dumanian G.A. Panniculectomy and the Separation-of-Parts Hernia Repair: A Solution for the Large Infraumbilical Hernia in the Obese Patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1006-1012.

Rosen M.J., Williams C., Jin J., McGee M.F., Schomisch S., Marks J., Ponsky J. Laparoscopic versus open-component separation: a comparative analysis in a porcine model. Am J of Surg. 2007;194(3):385-389.

Saulis A.S., Dumanian G.A. Periumbilical rectus abdominis perforator preservation significantly reduces superficial wound complications in ‘separation of parts’ hernia repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2275-2280.

Shestak K.C., Edington H.J., Johnson R.R. The separation of anatomic components technique for the reconstruction of massive midline abdominal wall defects: anatomy, surgical technique, applications, and limitations revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:731-738.

Taylor G.I., Palmer J.H. The vascular territories (angiosomes) of the body: experimental study and clinical applications. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:113.

The Ventral Hernia Working Group, Breuing K., Bulter C.E., Ferzoco S., Franz M., Hultman C.S., Kilbridge J.F., Rosen M., Silverman R.P., Vargo D. Incisional ventral hernias: Review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010. epub