CHAPTER 18 Peritoneal dialysis catheter placement

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ The peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter should enter the abdomen through the rectus muscle medial to the epigastric vessels, with the inner cuff positioned at the level of the parietal peritoneum.

♦ The PD catheter should exit the skin lateral to the abdominal entrance site, with the external cuff positioned approximately 2 cm from the exit site in a subcutaneous tunnel.

♦ The sites for catheter placement should be evaluated in the supine and sitting positions and in relation to undergarments to ensure that the patient can easily access the catheter. Placement below the belt line, within a skin fold, or in a location where body habitus and clothing cause catheter kinking or rubbing should be avoided.

♦ Previous abdominal incisions are not a contraindication to the laparoscopic approach but may direct the safest location for port placement.

♦ The course of the epigastric arteries must be visualized during port insertion through the rectus abdominis.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

♦ The indications for laparoscopic PD catheter placement are identical to those of PD catheter placement via conventional minilaparotomy, blind percutaneous Seldinger, or peritoneoscopic technique. Indications include an inability to tolerate hemodialysis (e.g., heart disease or extensive vascular disease) or a stated preference for peritoneal dialysis. The benefit of peritoneal dialysis is the ability to perform dialysis at home as long as the patient or an assistant has the capacity to perform exchanges properly.

♦ Laparoscopic PD catheter placement allows complete visualization of precise intra-abdominal implantation, the ability to perform adhesiolysis if required, and the ability to secure the catheter in the pelvis if desired. For these reasons, both surgeons and nephrologists increasingly prefer laparoscopic PD catheter placement in comparison to the older methods of percutaneous Seldinger technique, peritoneoscopic approach, and open placement via minilaparotomy.

♦ Contraindications to PD include the extensive adhesions that would prohibit adequate dialysate flow, an irreparable abdominal wall hernia, diaphragmatic defects predisposing to hydrothorax, and severe lung disease to a degree that increased intra-abdominal volume would compromise respiratory function. Morbid obesity is a relative contraindication.

♦ Most experts feel that the initial higher cost of laparoscopic PD catheter placement is more than offset by the lower incidence of costly later complications in comparison with open surgical placement or blind percutaneous placement.

♦ Appropriate preoperative teaching and arrangements for initial supervised sterile dressing changes should be made before operation.

Patient preparation and anesthesia

♦ Patients wash their abdomen with chlorhexidine the evening prior to surgery.

♦ In the setting of known constipation, an enema or suppository can be given preoperatively to facilitate rectosigmoid emptying.

♦ Hair is removed with electric clippers.

♦ Patients who continue to make urine empty their bladder immediately before operation or have a Foley catheter inserted.

♦ One to 2 grams of cefazolin IV is given 30 minutes before the operation.

♦ The patient is placed supine on a bed capable of Trendelenburg positioning.

Step 3: Operative steps

♦ The operative goals of PD catheter placement, all of which maximize function and prevent complications, include placement of the catheter tip deep in the dependent portion of the pelvis, appropriate positioning of the dual felt cuffs and subcutaneous portion of the catheter, and creation of a functional exit site.

♦ Multiple laparoscopic PD catheter placement techniques have been described, using a range of 1 to 3 laparoscopic ports. All techniques that allow for placement under continuous direct vision, including descriptions of a “1-port” approach, require at least 2 fascial defects. Although some surgeons call their technique “one-port”, they use one port for a camera and then another hole is made in the abdominal wall to insert the catheter without placing an actual laparoscopic trocar.

♦ Conventional minilaparotomy should be considered in patients with severe cardiopulmonary disease who may not tolerate pneumoperitoneum.

♦ The abdomen is widely prepped from the xiphoid to the pubis, allowing for the possibility of a midline laparotomy.

Two-port technique

Access and port placement

♦ Incision locations are marked on the patient after placing the PD catheter in the desired location on the abdomen as a guide. With the distal catheter coil overlying the superior pubis, the eventual location of the deep cuff is marked on the skin. This point corresponds to the anticipated trocar entry point through the fascia into the peritoneum.

♦ A 5-mm curvilinear incision is made just below the umbilicus, and the subcutaneous tissue is spread bluntly. If previous periumbilical or midline incisions are present, this initial port placement can be made lateral to the rectus muscle near the level of the umbilicus. In patients who have had previous extensive abdominal surgery, placement of the initial trocar is best performed with a cutdown under direct vision.

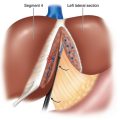

♦ With upward traction on the abdominal wall, a Veress needle is placed via this incision through the midline fascia. The intraperitoneal position is confirmed with a hanging drop test and low-pressure readings on initiation of insufflation. The peritoneal cavity is then insufflated to 15 mmHg with carbon dioxide (Figure 18-1).

♦ A 5-mm trocar is placed into the abdomen through the infraumbilical incision, through which a 5-mm 30-degree laparoscopic camera is placed.

♦ Diagnostic laparoscopy is undertaken with attention directed to identifying any inguinal or abdominal wall hernias requiring prophylactic repair or adhesions or omental redundancy that could potentially obstruct pelvic placement or catheter drainage.

♦ In the event that adhesiolysis, omentectomy, or tacking up of redundant omentum proves necessary to allow pelvic placement of the catheter, a third 5- to 10-mm working port is placed through the contralateral abdominal wall.

♦ A second 8-mm horizontal stab incision is made 4 to 5 cm lateral and 2 to 3 cm inferior to the umbilicus. An 8-mm nonbladed trocar (Ethicon Excel B8LT; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) is advanced subcutaneously in a medial and slightly caudal trajectory toward the pelvis. A 5- to 6-cm subcutaneous tunnel is created before angling the trocar perpendicular to the abdominal wall and piercing the intervening fascia and peritoneal envelope. Care should be taken to direct the trocar through the rectus abdominis muscle medial to the epigastric vessel, which can often be visualized with the laparoscope. All intraperitoneal manipulations should be done under direct vision.

Equipment description

Introduction of peritoneal dialysis catheter

♦ A 62-cm curled-tip peritoneal dialysis catheter with two felt cuffs (Kendall Quinton Curl Cath, Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts) is inserted into the 8-mm trocar with the aid of a flexible Bard ureteral stylet and directed to the pelvis under direct camera vision. It should be noted that a 7- to 8-mm trocar must be used, as the Dacron cuffs of the PD catheter will not pass through a trocar smaller than 7 mm (Figure 18-2).

♦ Once the catheter is intraperitoneal, the stylet is withdrawn approximately 4 to 5 cm to allow the curled atraumatic catheter tip to form, and the catheter is directed deep into the retrovesicle space. The stylet is slowly removed while ensuring the curved tip remains in the desired location.

♦ The catheter is then positioned such that the inner cuff lies just exterior to the level of the parietal peritoneum so the optimal scarring in of the catheter can take place. The catheter is secured by hand externally, and the trocar is then carefully removed over the catheter, while ensuring that the inner cuff remains in position and the outer cuff lies fully within the subcutaneous tunnel (Figure 18-3).

♦ The catheter exit site should allow the catheter to point medially as it exits the skin and serves to further separate the external cuff from the exit site.

Subcutaneous tunnel

♦ A small stab incision the width of the catheter is made slightly inferior and lateral to the 8-mm external wound. A tonsil clamp is advanced to create a short arcing tunnel, and the end of the catheter is grasped and brought out of the skin incision. No securing suture is used at this site. Alternatively, a Faller stylet can be attached to the end of the catheter and directed from lateral incision through the new exit site.

Completion of procedure

♦ Catheter function is tested by injection of 60 cc and aspiration of 30 to 40 cc of heparinized Normal Saline (1000 U/L).

♦ Proper positioning of the catheter is confirmed with the camera before trocar removal and desufflation of the abdomen (Figure 18-4).

♦ A sterile extension to the PD catheter is attached if available. The fascial defects do not require closure. The two skin incisions are closed with a 4-0 subcuticular Monocryl suture and Steri-Strips. Sterile adhesive dressings are applied.

Laparoscopic-guided technique with quinton percutaneous insertion kit

♦ Intraperitoneal insufflation and camera access is obtained as described earlier.

♦ A Quinton percutaneous insertion kit (Tyco Healthcare Group LP, Mansfield, Massachusetts) is used for catheter placement through the rectus muscle in a paramedian location inferolateral to the umbilicus. The kit allows placement of a 16 Fr Pull-Apart introducer sheath via Seldinger technique. A Swan Neck Curl-Cath double-cuffed PD catheter (Kendall Quinton Curl Cath, Tyco Healthcare Corp., REF 8888413401) is advanced through the sheath to the desired location. The leaves of the sheath are then pulled apart, leaving the catheter in place.

♦ Some authors utilizing this technique have described placement of an additional contralateral 2- to 5-mm port to allow use of a grasper to direct the PD catheter into the pelvis. Others have advocated use of a percutaneously placed permanent nylon loop on the peritoneal surface of the ipsilateral pelvic wall. The catheter is fed through the sheath as a means of pelvic fixation.

♦ An inferolateral exit site is fashioned with a stab incision and subcutaneous tunneling as described previously.

Presternal catheter placement

♦ Utilization of a Swan Neck Presternal Catheter (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts), a 112.8-cm catheter with an intraperitoneal component coupled to a long subcutaneous thoracic segment, has been described for patients in whom an abdominal exit site is not suitable because of body habitus, stomas, incontinence, or a preference for baths rather than showers. Intraperitoneal catheter placement is carried out laparoscopically as described earlier, though the catheter is introduced through the rectus muscle above the level of the umbilicus. The thoracic portion of the tubing is connected via a titanium connector to the abdominal component. A 2- to 3-cm parasternal incision is made at the level of the second interspace, and a subcutaneous pocket is created to accommodate the arced section of the thoracic segment, which allows the catheter to exit pointing inferiorly. The thoracic component is tunneled subcutaneously to this incision. Finally, the catheter is tunneled to the exit site stab wound several centimeters inferior to the parasternal incision. This technique is associated with low rates of infection and excellent overall long-term function.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ Ideally, the catheter should be secured in a stable position and not used for 4 to 6 weeks in order to allow scarring of the fascial defects and healing of the subcutaneous tunnel. A minimum of 2 weeks should be allowed from placement until use, because there is a higher incidence of catheter leakage when used within 2 weeks of placement.

♦ Sterile dressing changes should not occur more than once per week for 2 weeks. Gentle daily exit site cleansing can begin at 2 weeks, and showering can begin at 1 month if healing has been good. Use of sharp objects such as safety pins or scissors should be avoided around the catheter.

♦ Patients should avoid heavy physical activity including straining. Patients should wear loose-fitting clothing so that pressure is not placed on the catheter site.

♦ Patients should promptly report any systemic or local symptoms or signs of infection including pain, redness, or excessive drainage at surgical sites.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

Infectious complications

♦ Exit-site infection is signaled by purulent or bloody drainage around the catheter. It leads to peritonitis in 25% to 50% of patients. Culture-specific antibiotic therapy should be instituted for 2 to 6 weeks. Failure of medical therapy generally indicates cuff or tunnel infection and requires catheter removal. Tunnel infection is signaled by erythema, tenderness, or swelling over the subcutaneous catheter tunnel. Catheters can infrequently be salvaged by debridement of the infectious focus. However, catheter removal with either replacement through clean tissue planes (if there is no evidence of peritonitis) or delayed replacement after interval antibiotic treatment is almost always required.

♦ Peritonitis is the most common infectious complication of PD access. Peritonitis refractory to antibiotics or associated with a tunnel infection is an indication for catheter removal. Severe or recurrent infection often prompts transfer from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis.

Noninfectious complications

♦ Early leakage (<30 days), indicated by dialysate in the subcutaneous tissues, is caused by failure of the peritoneum to close around the catheter or at port sites. Treatment includes cessation of PD for 1 to 2 weeks and prophylactic antibiotics. Exploration of the catheter entry site into the abdomen or port sites and repair of the tissues around the cuff are required if conservative treatments fails.

♦ Late leakage (>30 days) of dialysate into the subcutaneous tissues often manifests as edema of the abdominal wall or drainage problems during dialysis. Open or laparoscopic exploration and repair of suspected leak sites are required.

♦ Catheter displacement complicates 2% to 30% of cases. It is manifest by flow dysfunction and poor catheter drainage. Migration out of the pelvis can also lead to pain caused by peritoneal irritation.

♦ Catheter obstruction may result in both inflow and outflow problems or isolated outflow failure. Obstruction of inflow and outflow is usually caused by clot or fibrin ingrowth into the catheter side holes. Thrombolysis can be attempted, but catheter replacement is often required. Outflow difficulty can be secondary to migration from the pelvis but also can be the result of adherent adjacent omentum or bowel acting as a one-way valve. Laparoscopic repositioning is often successful in this instance.

♦ Pericannular leaks and hernias complicate 1% to 27% of procedures.

♦ Superficial cuff extrusion is usually seen when the cuff is placed too close to the lateral incision. Alternatively, if the catheter is tunneled subcutaneously in such a way that the catheter is under tension, the memory of the tubing will cause the catheter to extrude outwardly over time, potentially causing exposure of the cuff.

♦ Hernias, which result from the increased intra-abdominal pressure generated by the dialysate infusion, are seen in 10% to 25% of patients on PD. Some of these occur at laparoscopic port sites. For this reason, trocar size should be the smallest possible to accommodate the PD catheter, camera, and additional instruments for adhesiolysis as required.

♦ Preoperative planning of the incisions and the exit site is crucial to successful catheter placement.

♦ Proper selection of trocars and instrumentation allows one to minimize the size of fascial defects and the risk of hernia formation without compromising laparoscopic visualization.

♦ Appropriate placement of both inner and outer cuffs and optimal tunneling is critical to durable catheter function and minimizes catheter complications.

Carrillo SA, Ghersi MM, Unger SW. Laparoscopic-assisted peritoneal dialysis catheter placement: a microinvasive technique. Surg Endosc. 2007;21;5:825-829.

Crabtree JH, Fishman A. A laparoscopic method for optimal peritoneal dialysis access. Am Surg. 2005;71(2):135-143.

Haggerty SP, Zeni TM, Carder M, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion using a Quinton percutaneous insertion kit. JSLS. 2007;11(2):208-214.

Harissis HV, Katsios CS, Koliousi EL, et al. A new simplified one port laparoscopic technique of peritoneal dialysis catheter placement with intra-abdominal fixation. Am J Surg. 2006;192(1):125-129.

Schmidt SC, Pohle C, Langrehr JM, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: implantation technique and results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17;5:596-599.

Twardowski ZJ. Peritoneal access: the past, present, and the future. Contrib Nephrol, 150. 2006:195-201.

Twardowski ZJ, Prowant BF, Nichols WK, et al. Six-year experience with Swan neck presternal peritoneal dialysis catheter. Perit Dial Int. 1998;18(6):598-602.