Perirectal Abscess and Fistula in Ano

Perirectal Abscess

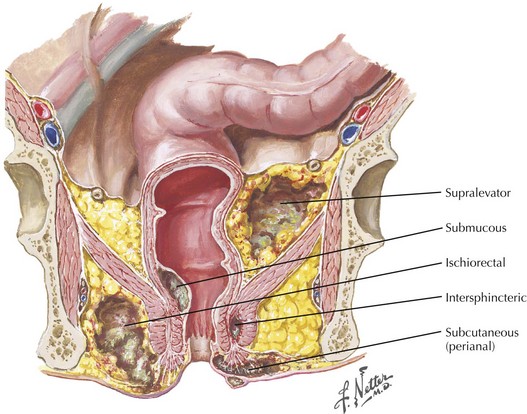

Anorectal abscess are defined by their anatomic relationship to the internal and external sphincter and levator musculature (Fig. 27-1). Abscesses that remain localized to the body of the gland in the potential intersphincteric space, between internal and external sphincters, are termed intersphincteric abscesses. Abscesses that perforate laterally through the external sphincter into the lower extrarectal space are called ischiorectal abscesses. The ischiorectal space is a pyramidal area bordered by the rectum and anus medially and pelvic side wall laterally. The apex of the ischiorectal space is formed by the levator ani muscle, and posteriorly the sacrotuberous ligament and gluteus maximus muscle form its borders. Importantly, the pudendal and internal pudendal vessels run through the superolateral wall of the ischiorectal space.

Surgical Management of Anorectal Abscess

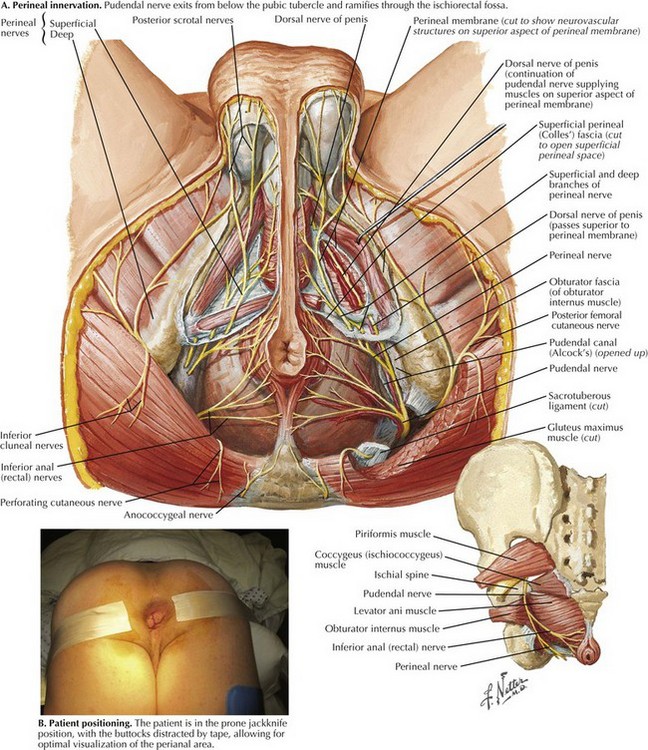

A perianal block is administered by injection of local anesthetic at the root of the pudendal nerve as it exits from Alcock’s canal just medial to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 27-2, A). The tubercle is easily palpated through the skin, and the needle is introduced medial to this, as deeply as possible. Additional local anesthetic is fanned out in a diamond shape adjacent to the sphincters, to infiltrate the ramifying branches of the nerve. Another option is to perform a ring block, in which local anesthetic is introduced into the perianal skin and the underlying sphincter muscle.

Specific Abscesses

Ischiorectal abscesses are deeper but they are approached in a manner similar to superficial abscesses. Whenever possible, these procedures should be done with the patient under anesthesia to allow for appropriate exposure and pain control. We routinely position the patient in the prone jackknife position, with buttock retraction using tape (Fig. 27-2, B). This position allows for optimal exposure for both surgeon and assistant. The incision should be large enough to allow for adequate drainage. Blunt dissection should be avoided to minimize damage to small nerves and blood vessels in the ischiorectal fossa. Packing of the abscess cavities is unnecessary and counterproductive to effective drainage and should be used only when needed to control hemorrhage.

Deep Postanal Space

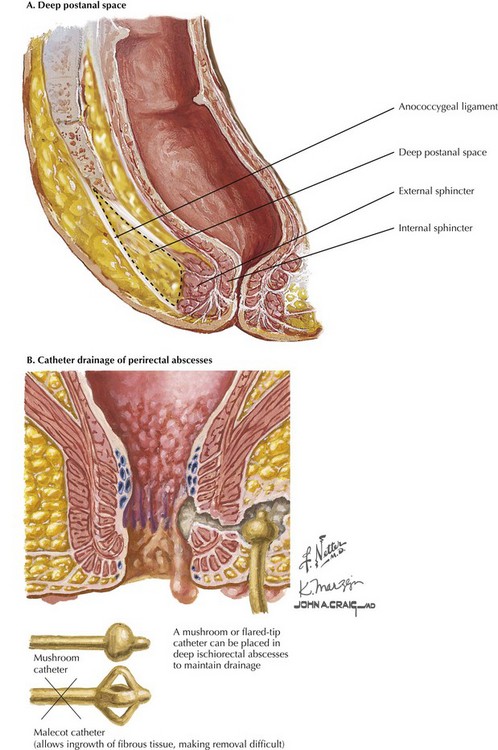

Effective management of these fistulas requires not only drainage through counterincisions over each ischiorectal space, but also unroofing of the deep postanal space. This approach requires division of the anococcygeal ligament and entry into this space (Fig. 27-3, A). The surgeon should work toward and just distal to the coccyx to guide the appropriate dissection. Division of the anococcygeal ligament and discharge of purulent fluid will confirm entry into this space.

Occasionally, deep ischiorectal fossa abscesses cannot be easily drained by superficial incisions. In these cases, drainage may be facilitated by placement of catheter with a mushroom or flared tip. This approach allows for continued drainage and development of a persistent tract, which will remain open after the catheter is removed (Fig. 27-3, B).

Fistula in Ano

Anatomic Description

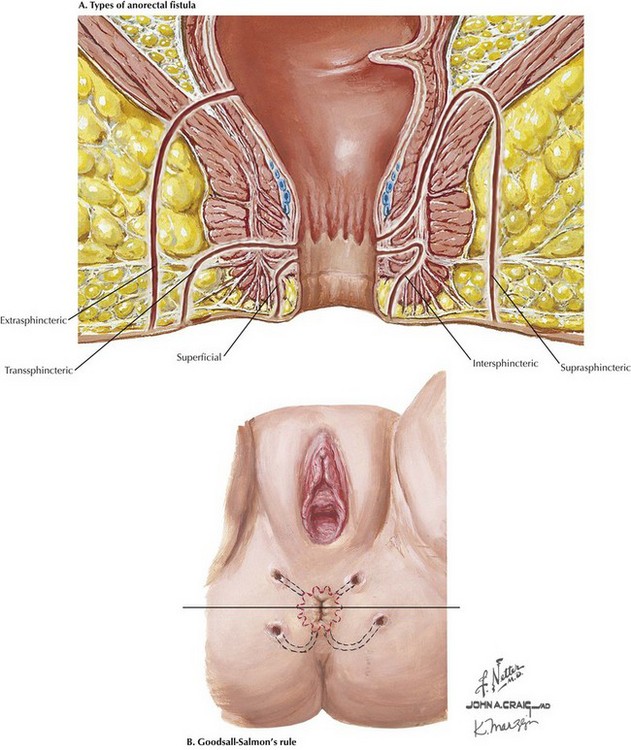

Fistulas are defined by their anatomic relationship to the pelvic floor musculature and sphincter complex (Fig. 27-4, A). The majority of fistulas track low through the subcutaneous soft tissue with minimal sphincteric involvement and are termed simple, or superficial. Simple lay-open fistulotomy is a time-honored and effective approach with a high success rate. Complex fistulas traverse a significant component of the sphincter or levator musculature and must be approached with caution. Performing a fistulotomy would require division of significant amount of sphincter muscle and may impair the continence mechanism.

The relationship of the external opening to the anal verge can offer clues as to the source of the internal opening using Goodsall’s rule: An imaginary line is drawn transversely across the anal opening, and fistulas anterior to this line generally track radially to internal rectal openings (Fig. 27-4, B). Fistulas posterior to this line, as well as those located greater than 2 cm from the verge, tend to originate from a posterior midline opening.

Preoperative Imaging and Patient Positioning

As mentioned earlier, patients are best examined placed in the prone jackknife position with the buttocks distracted with tape (Fig. 27-5, A). A headlight and Lockhart-Mummery fistula probes are important equipment that can facilitate identification of the tract.

Surgical Management of Anorectal Fistula

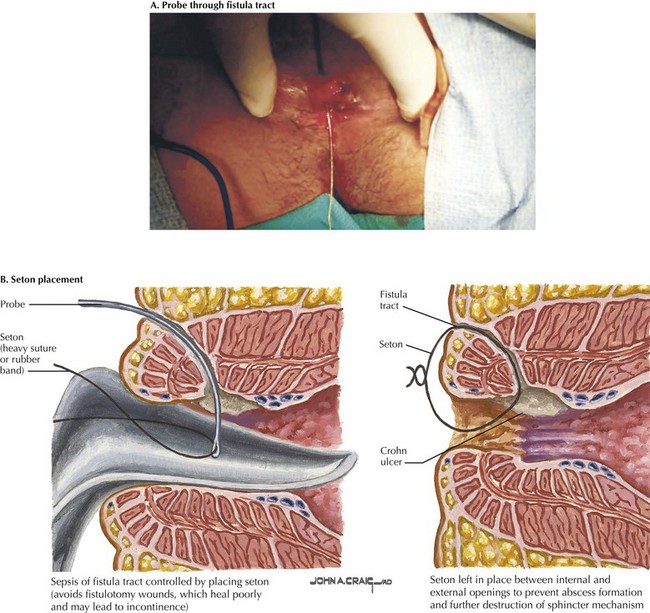

Complex fistulas are treated initially by management of local sepsis through adequate abscess drainage. To spare sphincter musculature, a draining seton is usually the initial step in management. Draining setons are biologically inert drains through the fistula tract to provide ease of egress of infected material (Fig. 27-5, B).

Abbas, MA, Lemus-Rangel, R, Hamadani, A. Long-term outcome of endorectal advancement flap for complex anorectal fistulae. Am Surg. 2008;74:921–924.

Bleier, JI, Moloo, H, Goldberg, SM. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract: an effective new technique for complex fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:43–46.

Champagne, BJ, O’Connor, LM, Ferguson, M, et al. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1817–1821.

Christoforidis, D, Pieh, MC, Madoff, RD, Mellgren, AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:18–22.

Dudding, TC, Vaizey, CJ, Kamm, MA. Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Ann Surg. 2008;247:224–237.

Garcia-Aguilar, J, Belmonte, C, Wong, WD, Goldberg, SM, Madoff, RD. Anal fistula surgery: factors associated with recurrence and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:723–729.

Hanley, PH. Conservative surgical correction of horseshoe abscess and fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 1965;8:364–368.

Johnson, JK, Lindow, SW, Duthie, GS. The prevalence of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury following childbirth: literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:547–554.

Lewis, RT, Maron, DJ. Anorectal Crohn’s disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:83–97.

Lindsey, I, Smilgin-Humphreys, MM, Cunningham, C, Mortensen, NJ, George, BD. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1608–1615.

Malik, AI, Nelson, RL. Surgical management of anal fistulae: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:420–430.

Rojanasakul, A, Pattanaarun, J, Sahakitrungruang, C, Tantiphlachiva, K. Total anal sphincter saving technique for fistula-in-ano: the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:581–586.

Swinscoe, MT, Ventakasubramaniam, AK, Jayne, DG. Fibrin glue for fistula-in-ano: the evidence reviewed. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9:89–94.