Peripheral neuropathies II

Clinical syndromes

Axonal neuropathies

Diabetic neuropathies

Autonomic neuropathy

can occur in association with sensory neuropathy or in relative isolation. The whole range of autonomic failure occurs with postural hypotension, a resting tachycardia, delayed gastric emptying with nausea and vomiting, intermittent diarrhoea and constipation, loss of bladder tone with retention and overflow, impotence and disordered sweating. Treatment is symptomatic (p. 114).

Other systemic diseases

Distal symmetrical axonal neuropathies are seen in a range of other systemic illnesses (Table 1), including hypothyroidism, uraemia, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. The connective tissue diseases can also cause vasculitic neuropathies.

| Systemic | Metabolic | Diabetes, etc. |

| Toxic | Neurotoxins, ethyl alcohol, etc. | |

| Nutritional | Vitamin B12 | |

| Extrinsic | Entrapment mononeuropathies | |

| Intrinsic | Metabolic | Refsum’s disease, etc. |

| Immunological | Demyelinating: Guillain–Barré syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy | |

| Vasculitis | ||

| Neoplastic | Monoclonal band | |

| Degenerative | Axonal neuropathies | |

| Infectious | Leprosy | |

| Genetic | Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, etc. |

Nutritional deficiencies

Patients with nutritional deficiencies (Box 1, p. 103) often have more than one vitamin deficiency. This can be associated with other problems such as alcoholism, in which the major factor is nutritional deficiency. The clinical presentation is of a painful, predominantly sensory distal symmetrical axonal neuropathy. Treatment is with appropriate vitamins. Vitamin B12 deficiency is more complicated because there is often an associated myelopathy (subacute combined degeneration of the cord). In the full syndrome, there is a progressive paraparesis, with loss of proprioception, prominent distal paraesthesiae and associated dementia. Vitamin B12 measurement and the demonstration of antiparietal cell antibodies and malabsorption of vitamin B12 give a diagnosis.

AIDS

Several different patterns of neuropathies are associated with HIV infection and AIDS. These are discussed on page 101.

Inherited neuropathies

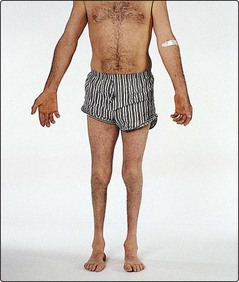

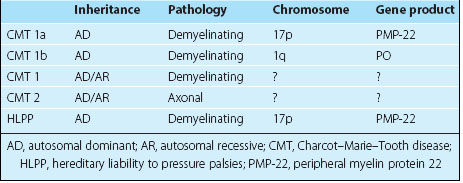

Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) disease is the most commonly inherited neuropathy. This was previously referred to as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN). The classification is primarily into the demyelinating form (CMT type 1) and the axonal form (CMT type 2). CMT 1 usually presents before age 30 years and is associated with peripheral nerve hypertrophy. CMT 2 can present later and patients are usually less severely affected. In both forms of CMT there is a preferential atrophy of the peroneal muscles to produce the ‘inverted champagne bottle’ legs (Fig. 1). The genetic basis for some of these has been elucidated (Table 2). There are some forms of CMT 1 and all forms of CMT 2 in which the genetic basis has not been established. Interestingly, a much rarer condition of hereditary liability to pressure palsies has been found to be due to different mutations in the same gene as CMT 1a.