10 Peripheral nervous system disorders

Part 1: Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS)

In GBS, the body’s immune system attacks these nerves, causing them to become inflamed (swollen). Although axonal demyelination is an established pathophysiological process in GBS, the rapid improvement of clinical deficits with treatment is consistent with Na+ channel blockade by antibodies or other circulating factors, such as cytokines [1]. Most people with GBS make a full recovery within a few weeks or months and do not have any further problems. Some people may take longer to recover and there is a possibility of permanent nerve damage.

Physiotherapy treatment

Recovery generally begins within a month of the height of the illness and has the potential to be complete. Unfortunately approximately 30% of patients will retain a residual paralysis or paresis, most usually in the lower limbs. Statistically significant correlations have been found between the degree of residual motor deficit and the severity of the weakness in the acute phase, the duration of the plateau phase or the duration of artificial ventilation [2].

Another complication to recovery is fatigue, so any exercises need to be carefully graduated in order to strengthen without overtiring the muscles. Temporary use of mobility aids such as wheelchairs and orthoses may be desirable to prevent overstrain. Patients with GBS do seem to have a reduced quality of life and functioning with persistent levels of distress even after the recovery period [3].

Acupuncture treatment

There is little or no useful research into the treatment of GBS by acupuncture, but it has been used in clinic. Chinese researchers claim that acupuncture used alongside medication improves the outcome during the rehabilitation phase [4]. A single case study was published some time ago by a couple of physical therapists and has some useful traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) ideas but carries little weight scientifically [5].

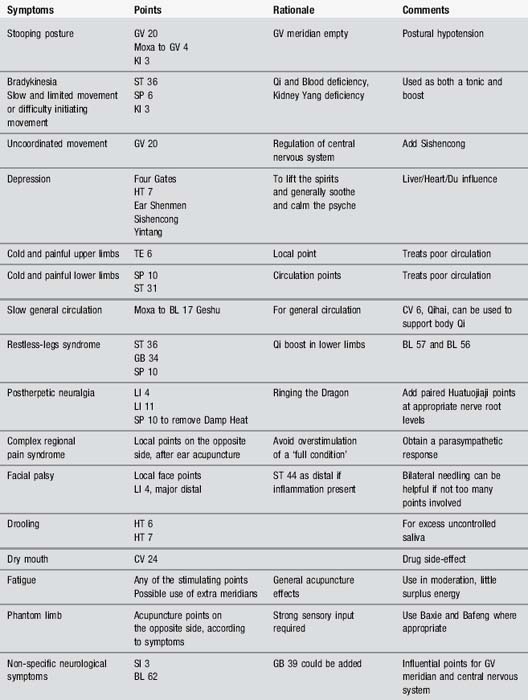

TCM theories

Part 2: Diabetic neuropathy

Research

Acupuncture has been used to control diabetic symptoms, most notably by Wang et al. [6], who treated the dyspeptic symptoms of gastroparesis by electroacupuncture at ST 36 Zusanli and LI 4 Hegu.

A small pilot study evaluated two clinical styles of acupuncture in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. Japanese acupuncture, characterized by very shallow needle insertion, was compared to traditional Chinese acupuncture [7]. Interestingly, those given Japanese acupuncture reported decreased neuropathy-associated pain according to daily diary scores whereas those in the other group reported minimal effects. Both styles lowered pain as measured by the McGill Short Form Pain Score. The TCM style improved nerve sensation according to quantitative sensory testing while the Japanese style had a more equivocal effect. However, with such a small group – only 7 patients in all – no significant conclusions can be drawn. It remains possible that acupuncture could be useful in this situation.

Further work on peripheral neuropathy was undertaken by a German group [8]. This was a larger study, with 47 patients involved, all of whom were evaluated over 12 months. The results suggested that nerve conduction showed an objective improvement with treatment. Acupuncture analgesia has been compared with standard medication and proved as successful in alleviating the pain from this type of neuropathy [9].

Several ideas have been put forward, including the use of acu-magnets on acupuncture points, particularly for diabetes and insomnia [10].

Bearing in mind that regrowth of peripheral nerves is possible, if the conditions are favourable and destruction has not been complete, acupuncture to improve the local tissue condition and increase local circulation may be very helpful [11].

Part 3: Bell’s palsy

Causes

The specific cause is not really known. This problem can occur after stroke or a transient ischaemic attack simply because of the muscle weakness involved in those conditions but true Bell’s palsy is thought to be caused more by an inflammatory episode in the facial nerve. The most common situations which may lead to this inflammation are systemic viral infections, local infections, trauma, surgery, diabetes, tumour, immunological disorders or drugs [12]. It is also thought that a persistent cold draught on the side of the face can cause this type of inflammation.

Differential diagnosis

This relies upon the presence of typical symptoms and signs, blood chemical investigations, cerebrospinal fluid investigations, X-ray of the skull and mastoid, cerebral magnetic resonance imaging or nerve conduction studies. Bell’s palsy may be diagnosed after exclusion of all secondary causes, but causes of secondary facial nerve palsy and Bell’s palsy may coexist [12, 13].

Case study 10.3: level 1 case study – acute facial palsy

Presenting symptoms

Objective assessment

Photographs were taken (no facial electromyogram was available) to record progress.

Acupuncture point selection – affected side only

TE 21, SI 19, GB 2, LI 20, ST 2, ST 6, ST 7, EX-HN 4, LI 4 (bilateral)

TCM texts suggested that only the affected side should be needled to direct flow to this area.

Part 4: Restless-legs syndrome (RLS)

Symptoms

If it is a severe case it is thought to warrant medical treatment. Restless-legs symptoms are dramatically relieved with levodopa and dopamine agonists, which are first-line treatment for this disorder. In addition, opioids have been shown to provide a marked symptomatic relief. This unique responsiveness of RLS to both dopaminergic agents and opioids places it at the crossroad of the two systems implicated in the placebo response. Indeed, in recent large-scale studies a substantial placebo response was observed [14].

RLS and acupuncture

With the clear response to dopamine agonists produced by acupuncture it is logical to suppose that acupuncture may be of value in this condition and indeed there is a current Cochrane review, although only two trials, with a total of 170 patients, met the inclusion criteria [15]. Borderline positive findings are recorded but, as with most reviews, it is agreed that further work is needed. Even if this is classified as a ‘placebo’ response by the researchers, the clinical use of acupuncture would still seem to be warranted.

Part 5: Postherpetic neuralgia

Acupuncture research

There has been little research of note in this condition although, clinically, acupuncture has a good reputation. Two well-written case studies offer some information [16, 17]. A small group of patients of mixed acute and chronic conditions demonstrated that acupuncture had diminished the pain [18].

Part 6: Phantom limb pain

Treatment

The condition is generally described as chronic and intractable and there are few medical remedies. Surgery involving the destruction of nerve tissue is sometimes used but is rarely of permanent value. Some new treatments are available, particularly that of using a ‘mirror box’ where the mirrored limb is reversed to look like the amputated one, giving the impression that the loss has been somehow reversed for the duration of the treatment. This is thought to be effective since changes to the way the peripheral areas of the body are represented on the cortex may lead to changes in pain sensation. The neuroplastic changes and the pain itself seem to be increased if a chronic painful situation has preceded them [19]. Stimulation of the sensorimotor cortex does seem to be able to reduce the pain [20].

[1] Vucic S., Kiernan M.C., Cornblath D.R. Guillain–Barré syndrome: an update. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(6):733-741.

[2] deJager A.E., Minderhoud J.M. Residual signs in severe Guillain–Barré syndrome: analysis of 57 patients. J Neurol Sci. 1991;104(2):151-156.

[3] Rudolph T., Larsen J.P., Farbu E. The long-term functional status in patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome. Euro J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1332-1337.

[4] Zou H. Clinical observation on 38 cases with Guillain–Barré syndrome treated with acupuncture combined with medicine. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture. 2001;12(2):171.

[5] Elgert G., Olmstead L. The treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy with acupuncture. Am J Acupuncture. 1999;27:15-22.

[6] Wang C., Kao C., Chen W., et al. A single-blinded, randomized pilot study evaluating effects of electroacupuncture in diabetic patients with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(7):833-839.

[7] Ahn A.C., Bennani T., Freeman R., et al. Two styles of acupuncture for treating painful diabetic neuropathy – a pilot randomised control trial. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(1–2):11-17.

[8] Schroder S., Liepert J., Remppis A., et al. Acupuncture treatment improves nerve conduction in peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(3):276-281.

[9] Abuaisha B.B., Costanzi J.B., Boulton A.J.M. Acupuncture for the treatment of chronic painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy: a long-term study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39(2):115-121.

[10] Colbert A.P., Cleave J., Brown K.A., et al. Magnets applied to acupuncture points as therapy a literature review. Acupunct Med. 2008;26(3):160.

[11] Green J., McClennon J. Acupuncture: an effective treatment for painful diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic Foot. 2006;9(4):182.

[12] Finsterer J. Management of peripheral facial nerve palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(7):743-752.

[13] He L., Zhou M.K., Zhou D., et al. Acupuncture for Bell’s palsy (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007. CD002914

[14] Fulda S., Wetter T.C. Where dopamine meets opioids: a meta-analysis of the placebo effect in restless legs syndrome treatment studies. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 4):902-917.

[15] Cui Y., Wang Y., Liu Z. Acupuncture for restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2008. CD006457

[16] Key S. A single case study of an 82 year old woman with depression and post-herpetic neuralgia. J Acupunct Assoc Chartered Physiotherapists. 2002;2002(2):47.

[17] Valaskatgis P., Macklin E.A., Schachter S.C., et al. Possible effects of acupuncture on atrial fibrillation and post-herpetic neuralgia – a case report. Acupuncture Med. 2008;26(1):51-56.

[18] Coghlan C.J. Herpes zoster treated by acupuncture. Cent Afr J Med. 1992;38(12):466-467.

[19] Flor H. Maladaptive plasticity, memory for pain and phantom limb pain: review and suggestions for new therapies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(5):809-818.

[20] Mackert B.M., Sappork T., Grusser S., et al. The eloquence of silent cortex: analysis of afferent input to deafferented cortex in arm amputees. NeuroReport. 2003;14(3):409-412.

[21] Bradbrook D. Acupuncture treatment of phantom limb pain and phantom limb sensation in amputees. Acupunct Med. 2004;22(2):93-97.

[22] Monga T.N., Jaksic T. Acupuncture in phantom limb pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62(5):229-231.