18 Peripheral Nerves

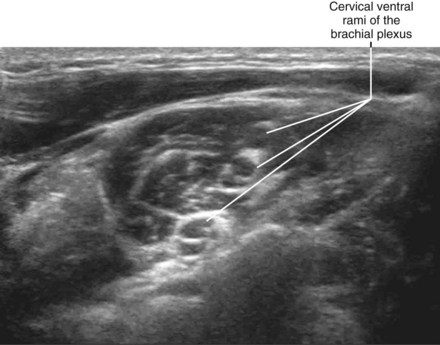

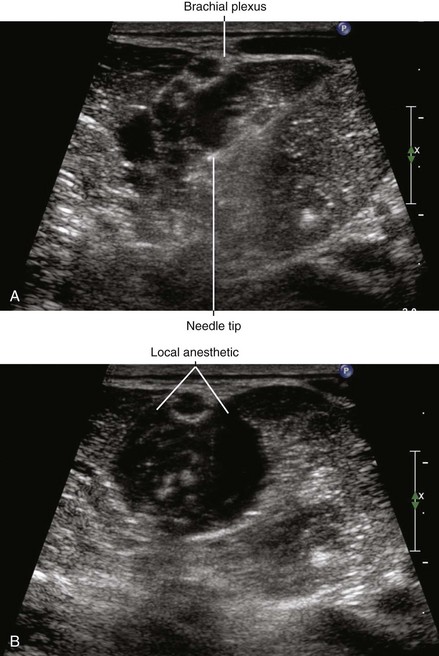

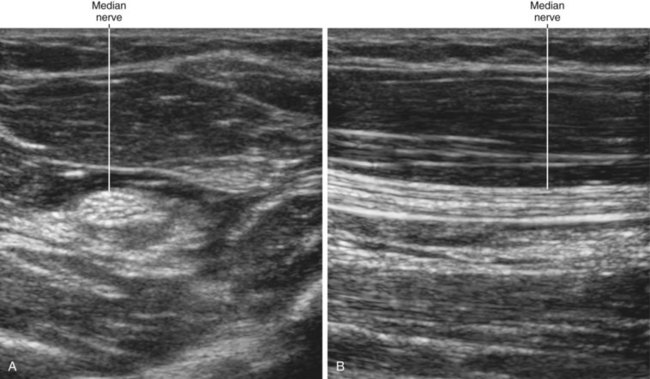

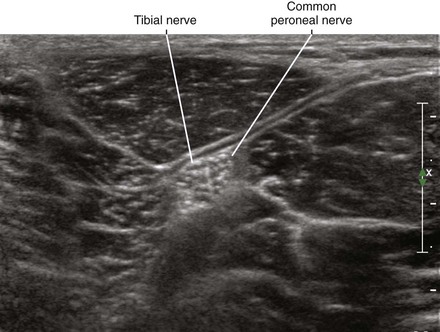

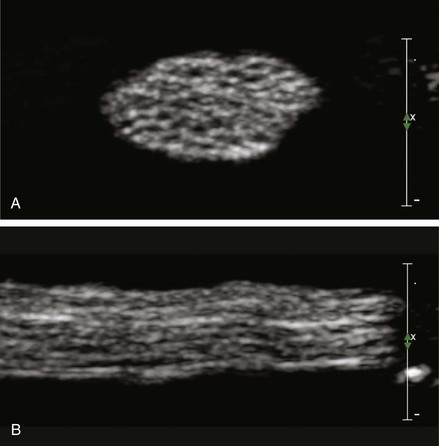

Peripheral nerves have a fascicular or “honeycomb” echotexture. This consists of the mixture of nerve fiber (hypoechoic) and connective tissue (hyperechoic) content within the nerve. Because there is little connective tissue within more central nerves (e.g., the cervical ventral rami of the brachial plexus), these nerves have a monofascicular or oligofascicular appearance on ultrasound scans.1 Nerves that are surrounded by hypoechoic muscle are usually easier to visualize than nerves that are surrounded by hyperechoic fat because the nerve borders are more evident.

Peripheral nerves have a complex architecture. Nerves are like a plexus within themselves, with fascicles combining and recombining internally along the nerve path. Because of this intertwined network, the fascicle count varies along the nerve path. Nerve sections taken 2 mm apart can have different fascicular patterns.2 The connective tissue content and fascicle count of peripheral nerves vary directly. That is, the amount of connective tissue is more abundant in multifascicular nerves.3 The connective tissue within nerves protects the fascicles from injury. Therefore, monofascicular nerves are more vulnerable to damage.

Identification of nerve fascicles is the basis of peripheral nerve imaging. With ultrasound, only a small subset of the total number of fascicles is imaged. In one study of ex vivo nerve specimens, only about one third the number of fascicles visible on light microscopy were visible on ultrasound scans.4 It is difficult for imaging technologies to resolve thin collagenous boundaries between adjacent fascicles. For these reasons, fascicular discrimination is a standard by which to judge nerve imaging quality.

High ultrasound frequencies (10-15 MHz) provide better resolution of nerve fascicles.5 However, at lower frequencies (7-10 MHz), peripheral nerves are still visible as cordlike structures.5 Commercial nerve imaging presets of imaging quality controls have been developed that enhance detection of nerve fascicles.

Among morphometric variables, the best correlate of nerve diameter is body height.6 The best correlate of nerve visibility on ultrasound scans is the extremity size.7

Clinical Pearls

• When nerves cross a tight passage, they assume a more homogeneous hypoechoic appearance from tight packing of the nerve fascicles.1

• When scanning superficial nerves, it is best to apply a generous amount of acoustic coupling gel (as if applying toothpaste to a toothbrush) to provide some acoustic standoff.8

• Sliding along the known course of a peripheral nerve with the nerve viewed in short axis can be useful for determining the edges of the distribution.

• The easiest way to obtain a long-axis view of a peripheral nerve is to view it in short axis and rotate the probe while keeping the nerve in the center of the field of view.

• The outer band of collagen does not always produce a distinct echogenic nerve border. This can make long-axis assessments of local anesthetic distribution difficult.

1 Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Santacroce E, et al. Brachial plexus sonography: a technique for assessing the root level. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:699–702.

2 Sunderland S. The anatomy and physiology of nerve injury. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:771–784.

3 Sunderland S, Bradley KC. The cross-sectional area of peripheral nerve trunks devoted to nerve fibers. Brain. 1949;72:428–449.

4 Silvestri E, Martinoli C, Derchi LE, et al. Echotexture of peripheral nerves: correlation between US and histologic findings and criteria to differentiate tendons. Radiology. 1995;197:291–296.

5 Giovagnorio F, Martinoli C. Sonography of the cervical vagus nerve: normal appearance and abnormal findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:745–749.

6 Heinemeyer O, Reimers CD. Ultrasound of radial, ulnar, median, and sciatic nerves in healthy subjects and patients with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1999;25:481–485.

7 Schwemmer U, Markus CK, Greim CA, et al. Sonographic imaging of the sciatic nerve division in the popliteal fossa. Ultraschall Med. 2005;26:496–500.

8 Thain LM, Downey DB. Sonography of peripheral nerves: technique, anatomy, and pathology. Ultrasound Q. 2002;18:225–245.