Chapter 17 Peripheral Nerve Stimulation

Open Technique

Background

For almost 40 years stimulation of peripheral nerves has been used for the control of neuropathic pain. Like spinal cord stimulation (SCS), the mechanism of peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) is believed to have its basis in the gate control theory of pain.1 Although PNS and SCS have been accepted techniques for the treatment of neuropathic pain, SCS has become more widely used. A number of factors have prevented the evolution of PNS, not least of which is a perception that PNS is an orphan modality. This has resulted in PNS never receiving the medical attention that it deserves from either manufacturers of implantable devices or implanting surgeons. Unfortunately, appropriate investigation of its scope and application remains latent.

Open surgical implantation of PNS electrodes, which was described between the early 1970s and 1990s, presaged the ongoing interest at selected centers in the United States and elsewhere to manage peripheral neuropathic pain by PNS.2–13

Another handicap for the development of PNS is the lack of any coordinated effort by the implanting physicians who have a vested interest in furthering the scope of PNS to engage in a dialog with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For example, a dialog to extend the current approval for the radiofrequency (RF) interface to include approval for an implantable power source implantable pulse generator (IPG) is wanting. Only one manufacturer, Medtronic (Minneapolis, Minn), has FDA approval to provide an electrode in conjunction with an RF external generator for PNS. All IPGs, whether Medtronic, Advanced Neuromodulation Systems (ANS, Plano, Tex), or Boston Scientific (Valencia, Calif), that are used in conjunction with PNS are considered “off-label” indications. The PNS (On-Point) electrode itself was originally developed as a quadripolar electrode for use in SCS. Recently PNS has received a boost through the efforts to develop occipital nerve stimulation.14,15

Definition

“Neuropathic pain is pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion, dysfunction, or transitory perturbation in the central or peripheral nervous system.”16

Indications

PNS is indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain in the distribution of a peripheral nerve or nerve trunk that is chronic and unresponsive to conventional medical management (CMM). Loss of function, an inability to participate in exercise therapy, and the nonresponse to local anesthetic or sympathetic blocks are considerations for PNS. Cases of neuropathic pain arising from a plexus injury or mononeuropathies from various causes may have in addition a partial or complete sensory loss that is within a particular nerve distribution. Common indications for open PNS are shown in Table 17-1.

Table 17-1 Indications for Open (Surgical) PNS Implant Using the FDA-Approved On-Point (Paddle) Electrode

| Brachial plexopathy | |

| Mononeuropathy | Upper limb |

| Radial nerve | |

| Median nerve | |

| Ulnar nerve | |

| Lower limb | |

| Sciatic nerve | |

| Peroneal nerve | |

| Anterior tibial nerve | |

| Posterior tibial nerve |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PNS, Peripheral nerve stimulation.

A number of conditions amenable to PNS are as follows: occipital neuralgia;17,18 postherpetic neuralgia;19,20 postherniorrhaphy pain;21 complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS);22 cluster headache;23–26 chronic daily headache;18,27 coccygodynia;28 fibromyalgia;29 cervicogenic pain;30,31 and migraine.32 Neurogenic pain following surgery for tarsal or carpel tunnel and postherpetic pain in a peripheral nerve distribution on the face, trunk, or limb are obvious indications for PNS. As a consequence of the foregoing indications, the contemporary unavailability of dedicated electrode designs should stimulate the engineering of nerve-specific electrode interfaces. Other potential sites for PNS are the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG)26 and other autonomic nervous system targets.

As is customary in every prospective case of SCS, it is essential to obtain a psychological evaluation for all potential PNS patients. This has been summarized by Doleys.33

Neuroanatomy

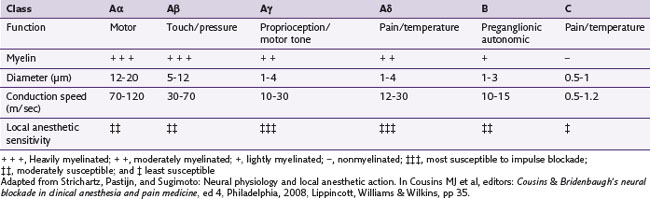

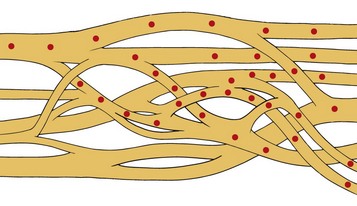

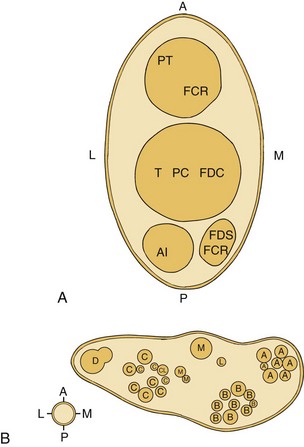

Myelinated nerve fibers have many concentric laminae that form from a single Schwann cell. The nodes of Ranvier are interruptions in the myelin sheath where the inward currents during depolarization are regenerated. An axon of a sensory neuron varies in diameter from as little as 2 µm to 11.75 µm.34,35 To facilitate regional distribution and therefore sensory coverage, nerve fibers divide into many branches, thereby allowing the innervation of a significant tissue mass by a single neuron. Clinically this results in referred pain that may originate in a single neuron being transmitted by branches to other tissues in the same region. The axon reflex is another mechanism that allows pain to be felt in undisturbed tissue. In this case antidromic transmission passes to other adjacent tissue, causing an expansion of the painful area. Table 17-2 lists the diameters of nerve fibers and their conduction velocities and function. The fascicular anatomy within nerve trunks is shown in Fig. 17-1. Figs. 17-1 and 17-2 show nerve fibers grouped within a thin laminated sheet (epineurium) that covers the axons.

A collection of nerve fibers (axon bundles) are known as fascicles. Each fascicle containing many axons is encased by a connective tissue layer and perineurium. The entire nerve is contained within a loose outer covering, the epineurium. Although fascicles vary in size from 0.04 to 4 mm, the majority are found between 0.04 and 2 mm in diameter. As nerves proceed distally, their fascicles begin to divide into smaller and smaller units and become more numerous. In addition, this organization takes on a topographically discrete nature, particularly in mixed (motor and sensory) nerves, and is responsible for providing an intimate view of the fascicular architecture.36–39 For example, in the ulnar nerve behind the medial epicondyle many nerve fibers are grouped into a single fascicle. A similar arrangement is found in the radial nerve in the spinal groove, the axillary nerve behind the humerus, and the common peroneal nerve in the lower thigh.

Blood Supply

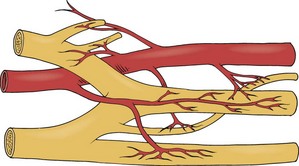

The vasa nervorum provide nutrition to peripheral nerves derived from collateral vessels, which are branches of adjacent veins and arteries (Fig. 17-3). Because of the dynamic nature of tissues and the translational movement of nerves, the vasa nervorum are quite tortuous. The magnitude of this movement increases in the vicinity of joints. There is considerable variation of the collateral blood supply throughout the length of each nerve. This has the effect of creating various watershed zones in each nerve between collateral sources. These zones of relatively poor nutrition may jeopardize the integrity of the nerve and cause increased stress such that extraneous compression or handling may compromise nerve function. In spite of the foregoing hazards, Ogata and Naito 199640 and Smith41 report that a reduced interneural blood flow during and/or after, for example, surgical resection of a nerve, is generally reestablished within 3 days.

Physics and Physiology Underlying Neurostimulation

The mechanism by which PNS achieves it effect is the activation of peripheral low threshold Aβ fibers, which in turn inhibit activity of small-diameter nociceptor Aδ and C fibers. Modulation of this nociceptor input is either direct through the selective activation of Aβ fibers, giving rise to inhibitory postsynaptic potentials or indirect via inhibitory spinal interneurons.42 Peripheral Aβ fiber activity most likely engages the medial lemniscal pathways, which in turn provide input to the ventral posterior medial nucleus of the thalamus, thereby overriding afferent input from spinothalamic tracts.43–45 These proposed mechanisms would have the effect of modulating activity from central sensitization at the dorsal horn. As a consequence, sensitization of supratentorial structures such as those involved in both cognitive and perceptual dimensions in the limbic system could render neurostimulation less effective or absent. Thus early application of this modality would be crucial to achieving its maximum effective potential. In contrast to SCS, PNS electrodes are placed on nerves affected by whatever is the ongoing neuropathic process; the primary action of peripheral neurostimulation tends to be direct inhibition of the first-order nociceptor and not second-order or higher neurons. It is clear that both allodynia and hyperalgesia, if present, are frequently reduced or eliminated by PNS. This suggests that sensitization can be subverted by suppressing peripheral nociceptor activity in the spinal cord and overriding nociceptor input at the thalamus. Given the constraints of slowing any temporal attempt on the progression of nociception, PNS may be more effective than SCS in providing inhibition at an interneuronal level.

Equipment

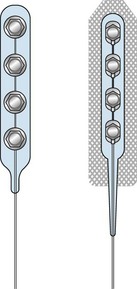

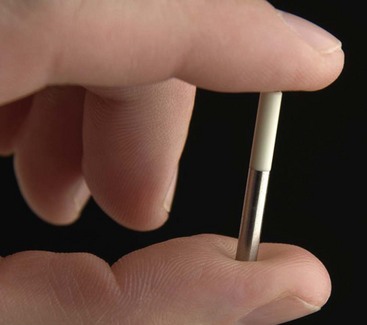

Only the On-Point and Quad Plus electrodes manufactured by Medtronic (Minneapolis Minn) are approved by the FDA for open PNS (Fig. 17-4). Other electrodes such as the Resume, Resume II, or Resume TL from Medtronic; the Artisan from Boston Scientific (Valencia, Calif); and the Quattrode and Axxess 6 from St. Jude Systems (Plano, Tex) are also used off label. For percutaneous PNS applications and trial, cylindrical wire type leads such as the Quad, Quad Plus, or Quad Compact from Medtronic and the Quattrode, Octrode, or Axxess from St. Jude, and Artisan from Boston Scientific are also used in an off-label basis.

Surgical Technique

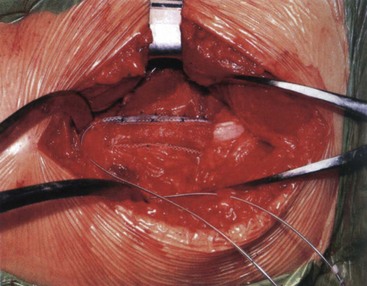

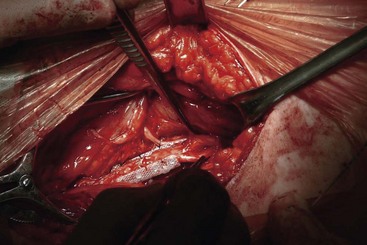

Access to the sciatic nerve is by an incision in the lateral thigh posterior to the iliotibial band. Dissection is carried down to the hamstring compartment, where the sciatic nerve lies between the adductor magnus and long head of biceps. Once identified, the sciatic nerve is carefully dissected from its bed while retaining its vasa nervorum and protecting any related muscular branches for a length sufficient to accommodate two On-Point electrodes (Figs. 17-5 and 17-6). Each electrode is placed adjacent to the tibial and peroneal components. To stabilize the two On-Point electrodes, their adjacent Gore-Tex skirts are sutured together using 4.0 nylon sutures. The two electrodes are then wrapped around the nerve as a “sandwich,” making sure that each bank of contacts is adjacent to the peroneal and tibial divisions, respectively. The free Gore-Tex edges are then tacked to the epineurium using 4.0 to 5.0 nylon sutures, taking care not to constrict the nerve. A pocket can be made either deep to the iliotibial band or under the deep fascia, whichever seems most appropriate at the time. The IPG can be retained in situ using 2.0 braided nylon or silk sutures to the fascia. This position has the advantage of avoiding the need to pass a long extension from the midthigh to a pocket in the buttock.

Because of the small current requirements of PNS, it is common to implant a nonrechargeable IPG. For most purposes a life of 9 to 12 years can be expected. Depending on the surgeon’s preference, pockets for the IPGs can be made in the gluteal area30 and abdominal wall.46

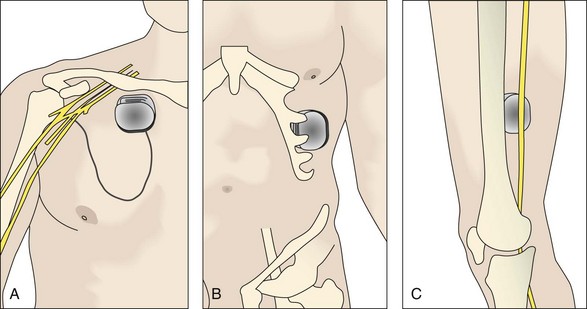

For PNS in the upper limb, both the ulnar and median nerves are found superficial and medial to the biceps brachii and medial head of the triceps (Fig. 17-7). The best surgical site for the radial nerve is in the spiral groove between the lateral and medial heads at the triceps and is found by dissecting the intermuscular septum. In each case, while protecting the collateral blood supply and preserving the motor branches to the triceps, a length of nerve sufficient to accommodate the On-Point electrode is dissected free. This is retained using 4.0 nylon sutures to the epineurium.

Outcomes Evidence

No prospective studies of PNS are currently available. A few case series and clinical reports provide an insight into the value of PNS. The most important from a functional point of view are described here. Hassenbusch and associates11 described 30 patients with CRPS II in whom symptoms had been present, in some cases for many years. Although 35% noted a decrement in analgesia over the first 2 years after implant, residual analgesia persisted at 15 years. Also noteworthy is the fact that 23% of these patients went back to work full or part time. Of the eight most recently published studies,47,48 a study of 17 patients by Novak and Mackinnon in 200049 described 60% (10 patients) having good to excellent pain relief, 4 with fair pain relief, and 3 with no adequate change in their symptoms at 21 months. However, a third of their patients returned to work. Eisenberg, Waisbrod, and Gerbershagen50 looked at data from three institutions: the Red Cross Center, Mainz; the Institute for Back Care, Bad Kreuznach; and the Linn Medical Center, Haifa. Earlier data (1985 to 1986) were compared with recent (1993 to 1995) data at the Red Cross, Mainz. Seventy-eight percent of the patients were regarded as good, and 22% as poor out of 46 total. It is also important to realize that these patients had failed CMM.

Mobbs, Nair, and Blum51 published data on 38 patients (M = F). Assessment was based on pain relief, narcotic use, function, and activities of daily living. Sixty percent had significant improvement in pain and return to work. No distinction between the response from workers’ compensation patients or noncompensable patients was found (p >0.05). Verbal pain scores were 5.1 with SD = 2.73, a figure that was acknowledged by an independent evaluation at 31 months.

From the foregoing, it is clear that PNS can be associated with good outcomes. Although the current indications for PNS include neuropathic pain resulting from trauma, surgical injury, and CRPS, new indications such as migraine and cluster headaches, trigeminal neuralgia, and fibromyalgia will have to await the development-specific electrodes. Certainly the relatively low invasive nature of open PNS will increase the attractiveness of this modality. The technique is reversible and testable; and, in comparison with ablative surgical options, there is no debate over its duration of effect. It has become an important clinical alternative. Complications associated with PNS are low and include local infection, hardware erosion, technical failure due to breakage or disconnection, fracture of current electrodes, and displacement.52–54

The almost complete absence of site-specific PNS electrode development has seriously handicapped progress of this modality. New electrodes with special arrays are in stark contrast to the level of sophistication now reached by functional electrical stimulation. Alternative spacing and lower profile need research if PNS is to be optimized. One completely new concept, an electrode termed BION,55–57 has the capability of enlarging the scope and indications for PNS (Fig. 17-8).

Cost-effectiveness and Future of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation

It should be clear from the foregoing that the results of managing neuropathic pain by PNS can be very effective. Unfortunately, the Psychological Pain Assessment Scale (PPAS) as a subjective measure is a poor determinant of any functional improvement that could be expected from the use of this modality. The use of quality-of-life measures is a better and more objective determination of device effectiveness. At least the debate regarding the role of pain measures is increasing.58,59

Following a review of 6000 citations by Health Technology Assessment,60 it was determined that there is significant value in terms of function, symptomatic relief, and cost-effectiveness for the use of SCS for CRPS, neuropathic, ischemic, and low back pain.

As already discussed, the scope of PNS remains largely unchartered and will rely on a considerable effort in the development and evolution of neural electrode interfaces. As already mentioned, the introduction of a self-contained electrode power source, the BION (Advanced Bionics, Valencia, Calif) is remarkable.55–57 Being without a lead or a separate implantable neurostimulator, it can be introduced through a small incision and easily directed to its target nerve. The device is small (3.3 mL, 27-mL length) with cathode and anode at each end. This device can be recharged externally and reprogrammed by telemetry. It is capable of a wide range of stimulation parameters—pulse width 1000 msec, a rate up to 1000 Hz, and an amplitude 12 mA. This is but a foretaste of the type of technical innovation that could propel PNS into the future. Although the scope of PNS has recently broadened by the use of percutaneous and subcutaneous leads, the need for dedicated electrodes on specific cranial nerves and other mixed peripheral nerves requires selective stimulation of afferent fibers with minimal effect on the motor and vasomotor components. Because of the highly selective distribution of PNS, in cases of SCS that lack a more regional topographical effect, PNS can be added to SCS to significantly improve the overall analgesia in the affected region.

1 Melzack RA, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.

2 Cauthen JC, Renner EJ. Transcutaneous and peripheral nerve stimulation for chronic pain states. Surg Neurol. 1975;4:102-104.

3 Kirsch WM, Lewis JA, Simon RH. Experience with electrical stimulation devices for the control of chronic pain. Med Instr. 1975;9:217-220.

4 Picazza JA, et al. Pain suppression by peripheral nerve stimulation. Part II. Observations with implanted devices. Surg Neurol. 1975;4:115-126.

5 Campbell N, Long DM. Peripheral nerve stimulation in the treatment of intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:692-699.

6 Nashold BSJr, Mullen JB, Avery R. Peripheral nerve stimulation for pain relief using a multi-contact electrode system. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:872-873.

7 Law JD, Swett J, Kirsch WM. Retrospective analysis of 22 patients with chronic pain treated by peripheral nerve stimulation. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:482-485.

8 Nashold BSJr, et al. Long-term pain control by direct peripheral nerve stimulation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64:1-10.

9 Waisbrod H, et al. Direct nerve stimulation for painful peripheral neuropathies. J Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67B:470-472.

10 Iacano RP, Linford J, Sandyke R. Pain management after lower extremity amputation. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:496-500.

11 Hassenbusch SJ, et al. Long term peripheral nerve stimulation for reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:415-423.

12 Stanton-Hicks M, Salamon J. Stimulation of the central and peripheral nervous system for the control of pain. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;14:46-62.

13 Shetter AG, Racz G. Peripheral nerve stimulation. In: North RB, editor. Management of pain. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1997.

14 Weiner RL, Reed KL. Peripheral neurostimulation for control of intractable occipital neuralgia. Neuromodulation. 1999;2:217-221.

15 Slavin KV, Burchiel KJ. Peripheral nerve stimulation for painful nerve injuries. Contemp Neurosurg. 1999;21(19):1-6.

16 Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, ed 2. Seattle, Wash: IASP Press; 1994.

17 Weiner RL. Peripheral nerve neurostimulation. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2003;14:401-408.

18 Weiner RL. Occipital neurostimulation for treatment of intractable headache syndromes. Acta Neurochir. 2007;97(suppl):129-133.

19 Dunteman E. Peripheral nerve stimulation for unremitting ophthalmic postherpetic neuralgia. Neuromodulation. 2002;5:32-37.

20 Johnson MD, Burchiel KH. Peripheral stimulation for treatment of trigeminal postherpetic neuralgia and trigeminal posttraumatic neuropathic pain: a pilot study. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:135-142.

21 Stinson LWJr. Peripheral subcutaneous electrostimulation for control of intractable postoperative inguinal pain: a case report series. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:99-104.

22 Monti E. Peripheral nerve stimulation: a percutaneous minimally invasive approach. Neuromodulation. 2004;7:193-196.

23 Schwedt TJ, et al. Occipital nerve stimulation for chronic cluster headache and hemicrania continua: pain relief and persistence of autonomic features. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1025-1027.

24 Magis D, et al. Occipital nerve stimulation for drug-resistant chronic cluster headache: a prospective pilot study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:314-321.

25 Leone M, et al. Stimulation for occipital nerve for drug-resistant cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:289-291.

26 Machado A, et al. A 12-month prospective study of gasserian ganglion stimulation for trigeminal neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2007;85:216-224.

27 Schwedt TJ, et al. Occipital nerve stimulation for chronic headache: long-term safety and efficacy. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:153-157.

28 Kothari S. Neuromodulation approaches to chronic pelvic pain and coccygodynia. Acta Neurochir. 2007;97(Pt 1):365-371. (suppl)

29 Slavin KV. Peripheral neurostimulation in fibromyalgia: a new frontier? Pain Med. 2007;8:621-622.

30 Kapural L, Mekhail N, Hayek SM, et al. Occipital nerve electrical stimulation via the midline approach and subcutaneous surgical leads for treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: a pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2005;1001:171-174.

31 Oh MY, et al. Peripheral nerve stimulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia and transformed migraine using a C1-2-3 subcutaneous paddle style electrode: a technical report. Neuromodulation. 2004;7:103-112.

32 Rogers LL, Swidan S. Stimulation of the occipital nerve for the treatment of migraine: current state and future prospects. Acta Neurochir. 2007;97(Pt 1):121-128. (suppl)

33 Doleys DM. Psychological factors in spinal cord stimulation therapy: brief review and discussion. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21(6):E1.

34 Peters A, Palay S, Webster H. The fine defined structure of the nervous system: the neuron and supporting cells. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1976.

35 Hubbard JI, editor. The peripheral nervous system. New York: Plenum Press, 1974.

36 Sunderland S. The intraneural topography of the radial, median and ulnar nerves. Brain. 1945;68:243-298.

37 Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries, ed 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1978.

38 Sunderland S. Nerve injuries and their repair: a critical appraisal. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1991. pp 31-45

39 DiRosa F, Giuzzi P, Battiston B. Radial nerve anatomy and vesicular arrangement. In: Brunelli G, editor. Textbook of microsurgery. Millan, Masson; 1988:571.

40 Ogata K, Naito M. Blood flow of peripheral nerve effects of dissection, stretching and compression. J Hand Surg (BC). 1986;11:10-14.

41 Smith JW. Factors influencing nerve repair. I. Blood supply of peripheral nerves. II Collateral circulation of peripheral nerves. Arch Surg. 1966;93:335. 433

42 DeLisa J, editor. Rehabilitation medicine: principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1993.

43 Giordano J. The neuroscience of pain and analgesia. In: Boswell MV, Cole BE, editors. Weiner’s pain management: a guide for clinicians. ed 7. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC; 2005:15-34.

44 Giordano J. Techniques, technology and tekne: the ethical use of guidelines in the practice of interventional pain management, commentary. Pain Physician. 2007;10:1-5.

45 Giordano J. Neurobiology of nociceptive and anti-nociceptive system. Pain Physician. 2005:277-290.

46 Hammer M, Doleys DM. Perineuromal stimulation in the treatment of occipital neuralgia: a case study. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:47-51.

47 Cooney WP. Chronic pain treatment of direct electrical nerve stimulation. In: Gelberman RH, editor. Operative nerve repair and reconstruction, vol II. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1991:1151-1161.

48 Strege W, et al. Chronic peripheral nerve pain treated with direct electrical nerve stimulation. J Hand Surg (Am). 1994;19:931-939.

49 Novak CV, Mackinnon SD. Outcome following implantation of peripheral nerve stimulator in patients with chronic pain. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1967-1972.

50 Eisenberg E, Waisbrod H, Gerbershagen HU. Lon-term peripheral nerve stimulation for painful nerve injuries. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:143-146.

51 Mobbs RJ, Nair S, Blum XP. Peripheral nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:216-221.

52 Shetter AG, et al. Peripheral nerve stimulation. In: North RB, Levy RM, editors. Management of pain. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1997.

53 Slavin KV, Wess C. Trigeminal branch stimulation for intractable neuropathic pain: a technical note. Neuromodulation. 2005;8:7-13.

54 Slavin KV, Nersesyan H, Wess C. Peripheral neurostimulation for treatment of intractable occipital neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:112-119.

55 Loeb GE, et al. BION system for distributed neural prosthetic interfaces. Med Eng Physics. 2001;23:9-18.

56 Carbunaru R, et al. Rechargeable battery-powered BION microstimulators for neuromodulation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2004;6:4193-4196.

57 Groen J, Amiel C, Bosch JL. Chronic pudendal nerve neuromodulation in women with idiopathic refractory detrusor overactivity incontinence: results of a pilot study with a novel minimally invasive implantable mini-stimulator. Neurol Urodyn. 2005;24:226-230.

58 Turk DC, Rudy TE, Stieg RL. The disability of determination dilemma: toward a multiaxial solution. Pain. 1988;34:217-229.

59 Birchiel KJ, Anderson VC, Brown FD. Prospective, multicenter study of spinal cord stimulation for relief of chronic back and extremity pain. Spine. 1996;21:2786-2794.

60 Simpson EL, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischemic origin: systematic and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assess. 2009;13(17):1-154.