CHAPTER 231 Peripheral Nerve Examination, Evaluation, and Biopsy

In this chapter we review the pertinent components of the history and physical examination for patients with focal peripheral nerve lesions. We do not attempt to illustrate examination techniques per se but instead focus on the overall diagnostic approach; technical references on examination of patients with focal peripheral nerve injuries are available.1–4 We also briefly comment on the application of supplemental imaging, electrodiagnostic studies, and intraoperative electrophysiology in confirming the diagnosis and monitoring patients over time. A more in-depth discussion of these tests, as well as further comment on the general approach to patients with peripheral nerve injuries and entrapments, can be found in other chapters of this text. We conclude with a discussion about the indications for and utility of peripheral nerve biopsy, which can be an indispensable component of the diagnostic evaluation for selected nerve conditions.

History

Pain

Pain is a frequent complaint after peripheral nerve damage, and its cause may be multifactorial.5 The location, quality (e.g., burning, paresthetic, crushing), exacerbating/relieving maneuvers, and any response to medication should be sought.

Both neuropathic and non-neuropathic types of pain may occur after nerve injury or entrapment. One common source of non-neuropathic pain is disuse-related swelling, joint stiffness, and shortening and fibrosis of muscles and tendons. Such pain may occur when affected limbs are immobilized or not adequately mobilized. Moreover, muscle paralysis causes alterations in joint stability and dynamics, thereby predisposing the patient to arthropathy and pain from pathologic strain (e.g., patients with sciatic or peroneal nerve injury often have lower back or hip pain secondary to their asymmetric gait). Autonomic disturbance may also cause significant pain in these patients and is a hallmark of both type I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) and type II (causalgia) complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).6 CRPS type I usually occurs after a minor injury to the extremity (e.g., sprained ankle), whereas CRPS type II occurs after significant damage to a major mixed nerve (e.g., gunshot wound). Severe burning pain, careful attempts to protect the involved extremity from movement or manipulation, and evidence of autonomic overactivity are cardinal features of CRPS. Another type of pain that may occur with nerve injury is avulsion pain (i.e., deafferentation pain), which is a result of nerve root avulsion from the spinal cord. Avulsion pain is usually manifested as a constant burning or crushing pain that is poorly responsive to any intervention short of dorsal root entry zone ablation.7 Regenerating nerves may also produce pain, which is often described as tingling, electric shocks, and dysesthesias along the course of the nerve. Injured nerves, especially small cutaneous branches, demonstrate a profound capacity to regenerate. When they extend into a scar or superficial area, painful neuromas may form. Patients with neuromas usually describe localized pain with a trigger point overlying an often palpable, exquisitely tender subcutaneous lesion. A diagnostic trigger point injection of lidocaine or bupivacaine near the neuroma can frequently confirm this diagnosis.

With peripheral nerve entrapment, pain is often referred adjacent to and along the distribution of the compressed nerve. For example, the description of aching discomfort in the wrist and forearm, along with nocturnal symptoms, including paresthesias in the median nerve distribution, is so characteristic that it is virtually diagnostic of carpal tunnel syndrome. Pain and tenderness may also be present at the entrapment site (e.g., near the retrocondylar groove with ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow). When peripheral nerves that do not contain cutaneous sensory afferents are compressed, numbness and paresthesias do not occur, but frequently a deep aching pain is felt not only at the point of entrapment but also within any joints from which the entrapped nerve carries proprioceptive sensation (e.g., shoulder pain during the early stages of suprascapular entrapment). Along with pain, significant damage to a motor-sensory nerve also produces concomitant sensory abnormalities, including paresthesias, hypoesthesias, and hyperesthesias, characteristically in a well-defined region that represents the nerve’s sensory territory.8 Quantitative sensory testing may reveal either an increase (hyperesthesia) or a decrease (hypoesthesia) in response to varying thresholds.9 When there is no sensory loss or if it involves more than one peripheral nerve territory, other diagnoses must be considered, including radiculopathy, musculoskeletal injury, nonfocal neuropathies, and CRPS.

Physical Examination

Inspection

The examination always begins with visual assessment of the affected limb or body region in comparison to the normal side. Muscular atrophy, traumatic and surgical scars, swelling, hair loss, perspiration patterns, erythema, and abnormal joint and limb positions are all noted (Fig. 231-1). The muscle atrophy may be profound or subtle, and the examiner must often take a step back and review the gestalt of the patient’s body symmetry. Autonomic nervous system abnormalities may include swelling, hair loss or gain, variability in sweating and vasodilation, and Horner’s syndrome. Previous scars and past operations should be questioned, especially those that may be related to the nerve in question. Protection and favoring of the injured limb are also obvious during inspection and may indicate severe neuropathic pain or CRPS. Baseline photographs may be useful for long-term follow-up and assessment of treatment efficacy.

Motor Examination

Motor testing is perhaps the most objective and reproducible aspect of the neuromuscular examination. Adhering to the principles outlined earlier, the examiner compares the involved and the normal extremity with respect to bulk, tone, and strength. As indicated, each individual muscle is tested. Strength is rated with the British Medical Research Council system (Table 231-1) or the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center system.3 The scope of this chapter does not allow detailed analysis of the key steps in testing each and every muscle, which may be reviewed elsewhere.1–4

TABLE 231-1 Motor Function Grading Scale of the British Medical Research Council

| GRADE | FUNCTION |

|---|---|

| 5 | Full strength |

| 4 | Movement against resistance |

| 3 | Movement against gravity only |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 1 | Muscle contraction but no movement |

| 0 | No muscle contraction |

An appreciation of hand function and deficits after upper extremity nerve injuries is especially important8 (Fig. 231-2). For example, a patient with an anterior interosseous nerve palsy fails to make an “O” when the tip of the thumb and index finger are brought in apposition. Instead, the pulp of the distal ends of the fingers touch because the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus to the index finger are weak. The previously mentioned ulnar clawhand occurs when the patient is asked to actively open the hand and is a hallmark of ulnar nerve injury. Conversely, median nerve injury produces a “Benedictine hand” in which the first two or three digits fail to properly flex when the patient is instructed to make a fist. Finally, a simian hand occurs when there is clawing of all the digits as a result of injury to both the median and ulnar nerves (or medial cord/lower trunk).

Sensibility Testing

The sensory examination includes testing for light touch, pinprick, two-point discrimination, vibration sense, temperature sense, and proprioception.10,11 A common feature of a complete peripheral nerve injury is the loss of all modalities of sensation in the distribution of the nerve. With incomplete or partial injuries, however, some modalities may be affected more so than others. Nerve entrapment syndromes are an example in which modalities of discriminative touch, which reflect receptor density, may be affected more than others. Thus, in these patients the loss of moving two-point discrimination may occur before the loss of other sensory modalities.12

To obtain a rapid estimation of the region of sensory loss, patients are instructed close their eyes and point to areas that are stimulated with a blunt object such as a dull pen tip. This simple technique allows the clinician to map the area of poor or absent sensation. Having the patient compare simultaneous stimulation (either in the contralateral limb or in a normal region of the affected limb) can allow a more subtle loss of sensation to be discerned. Attempts to validate a simultaneous sensory testing paradigm with a 10-point analog scale have been reported.11 A more thorough sensory examination can be done with the most rudimentary instruments, such as a safety pin, cotton wool, a 128-Hz tuning fork (for both vibration and temperature sense), and either paper clips, blunt-tipped calipers, or a commercially calibrated device for two-point discrimination.

Sensory loss may be graded from 5 (normal or nearly normal sensation) to 0 (insensate), and such grading is used to provide a baseline for follow-up sensory examinations (Table 231-2). As with motor function, grading of sensation is important for documenting subsequent improvement or worsening, as well as to provide a standard for comparison of treatment outcomes.

| GRADE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 5 | Nearly normal response to touch and pinprick |

| 4 | Localized, subnormal response to touch and pinprick; no over-response |

| 3 | Nonlocalized, subnormal response to touch and pinprick; some over-response |

| 2 | Enough for slow protection; mislocalized with over-response |

| 1 | Hypoesthesia and/or paresthesia; deep pain |

| 0 | No response |

Other Clinical Tests

An injured nerve often exhibits overlying mechanical hypersensitivity. Evoking a shock-like electrical sensation or paresthesias along the nerve’s distribution by percussing over the injured segment is called a Hoffman-Tinel sign.13 This sign is frequently found over the nerve in an area of entrapment and can remain present for a long period, sometimes indefinitely. When a Hoffman-Tinel sign is found to be advancing along the anatomic distribution of the nerve, particularly if it does so at the expected rate of nerve regeneration, approximately 1 mm/day or 1 inch/mo, this provides evidence of ongoing regeneration. Even though an advancing Hoffman-Tinel sign may be a positive indicator of regeneration, it is associated with subsequent muscle reinnervation and functional recovery in only approximately half of patients. In contrast, the lack of an advancing Hoffman-Tinel sign may be a strong negative finding suggesting complete neural interruption or poor regeneration.3

Additional provocative maneuvers may be used to instigate transient symptoms (usually paresthesias) from nerve entrapment. For instance, a Phalen test (passive flexion of the wrist for 1 minute causing paresthesias in the median nerve distribution) helps confirm the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.14 Conversely, many tests for thoracic outlet syndrome, such as the modified Adson, Roos, and others, have not been validated and have questionable significance.15

In patients with nerve sheath tumors, a careful history plus physical examination of the skin for stigmata of neurofibromatosis is important.16 With regard to the lesion itself, if it is palpable, mobility of the tumor with respect to the underlying nerve is sought. Specifically, nerve sheath tumors are generally mobile in a side-to-side manner but not along the nerve trajectory. Tapping on the tumor causes a positive Hoffman-Tinel sign, which helps confirm its parent nerve of origin. In fact, it remains good clinical practice to palpate the complete length of any peripheral nerve affected by entrapment or idiopathic palsy to exclude a nerve sheath tumor. Imaging is required for the evaluation of any mass lesions affecting a peripheral nerve.

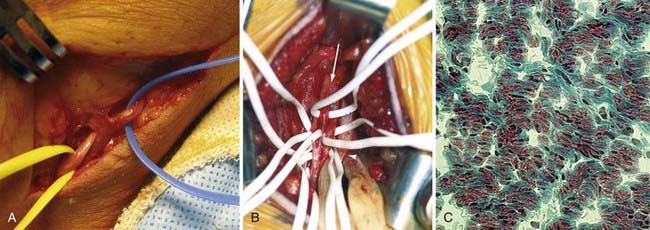

Biopsy

Biopsy of a peripheral nerve lesion is often indicated when the results could alter the patient’s treatment and outcome (Fig. 231-3). The most frequent indication for nerve biopsy is as part of the diagnostic evaluation for diffuse (focal and nonfocal) peripheral neuropathies. Histologic examination of the sural nerve is commonly performed to exclude various inflammatory neuropathies, amyloid neuropathy, and focal leukemias or lymphomas affecting the peripheral nerves (i.e., neuropathies that are rare but have effective treatments that cannot be used empirically because of potentially serious side effects). Another indication for nerve biopsy is when the neurophysiologist cannot determine whether the muscle weakness is neurogenic or myogenic; such patients often undergo concurrent muscle biopsy. Before nerve biopsy, the nerve to be excised should be confirmed to be affected based on clinical deficits or electrodiagnostic findings, or both; usually, absent or delayed nerve conduction velocity is present. The sural nerve is frequently the nerve of choice for biopsy because it is reliably located and the postoperative sensory deficit is generally acceptable to the patient. Other nerves commonly subjected to biopsy include the superficial peroneal nerve distal to the innervation of the peroneus longus and brevis and an obturator branch to the gracilis muscle when a pure motor neuropathy is suspected. In fact, by using intraoperative nerve action potentials, evoked electromyography, sensory evoked potentials, and microscopic neurolysis, almost any surgically accessible nerve may safely undergo biopsy.17

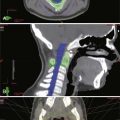

Incidental nerve sheath tumors in patients without neurofibromatosis are rarely malignant and can usually be diagnosed by MRI characteristics alone. Therefore, they infrequently require open or needle biopsy when surgical resection is not otherwise indicated. Conversely, when malignancy is suspected in a nerve sheath tumor, biopsy is mandatory. Risk factors for malignancy include neurofibromatosis, plexiform neurofibromas, large tumors (>5 cm), pain, rapidly growing tumors, and tumors with high metabolic rates on [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. In these patients, multiple biopsy samples are taken from electrically silent areas of tumor, including any “hot spots” on PET imaging.18 Oncologic and segmental resection with removal of major peripheral nerves is performed only after the final histologic diagnosis is obtained, which requires a second surgical procedure, before or after radiation therapy.

Another indication for nerve biopsy includes serial intraoperative assessment of proximal nerve stumps for viability as a source of regenerating axons.19 Although some authors recommend specific stains, the basic technique usually begins with frozen sections to assess for the presence and organization of myelinated axons and the extent of scarring. Although subjective, when minimal scarring and fascicular disorganization are present, the proximal stump is considered an adequate source of regenerating axons (Fig. 231-3C). This may be useful when the potential for regeneration is uncertain based on clinical examination, radiographic studies, and intraoperative findings if the proximal rootlets have been avulsed from the spinal cord.

Bowden RE, Napier JR. The assessment of hand function after peripheral nerve injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:481-492.

, 2000 Brain Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2000.

Burchiel KJ, Ochoa JL. Surgical management of post-traumatic neuropathic pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:117-126.

Devor M. The pathophysiology and anatomy of damaged nerve. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, Bonica JJ, editors. Textbook of Pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984:49-64.

Dyck PJ, Thomas OK. Diabetic Neuropathy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999.

Ferner RE, Golding JF, Smith M, et al. [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) as a diagnostic tool for neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs): a long-term clinical study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:390-394.

Ghobrial IM, Buadi F, Spinner RJ, et al. High-dose intravenous methotrexate followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as a potentially effective therapy for neurolymphomatosis. Cancer. 2004;100:2403-2407.

Hislop HJ, Montgomery J. Daniels and Worthington’s Muscle Testing: Techniques of Manual Examination, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Hoffman P, Buck-Gramcko D, Lubahn JD. The Hoffmann-Tinel sign. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:800-805.

Kim DH, Midha R, Murovic JA, et al. Kline and Hudson’s Nerve Injuries: Operative Results for Major Nerve Injuries, Entrapments, and Tumors, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008.

Lwu S, Midha R. Clinical examination of brachial and pelvic plexus tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(6):E5.

Moberg E. Methods for examining sensibility of the hand. In: Flynn J, editor. Hand Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1975:295-304.

Murji A, Redett RJ, Hawkins CE, et al. The role of intraoperative frozen section histology in obstetrical brachial plexus reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24:203-209.

O’Neill OR, Burchiel KJ. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in painful nerve injury. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:127-136.

Pang D, Wessel HB. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:105-121.

Patel MR, Bassini L. A comparison of five tests for determining hand sensibility. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1999;15:523-526.

Russell SM. Examination of Peripheral Nerve Injury: An Anatomical Approach. New York: Thieme; 2006.

Suarez GA, Dyck PJ. Quantitative sensory assessment. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Dellon AL, editors. Evaluation of Sensibility and Re-education of Sensation in the Hand. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1981:1-263.

Vargas Busquets MA. Historical commentary: the wrist flexion test (Phalen sign). J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:521.

1 Brain Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2000.

2 Hislop HJ, Montgomery J. Daniels and Worthington’s Muscle Testing: Techniques of Manual Examination, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

3 Kim DH, Midha R, Murovic JA, et al. Kline and Hudson’s Nerve Injuries: Operative Results for Major Nerve Injuries, Entrapments, and Tumors, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008.

4 Russell SM. Examination of Peripheral Nerve Injury: An Anatomical Approach. New York: Thieme; 2006.

5 Burchiel KJ, Ochoa JL. Surgical management of post-traumatic neuropathic pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:117-126.

6 O’Neill OR, Burchiel KJ. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in painful nerve injury. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:127-136.

7 Bowden RE, Napier JR. The assessment of hand function after peripheral nerve injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:481-492.

8 Devor M. The pathophysiology and anatomy of damaged nerve. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, Bonica JJ, editors. Textbook of Pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984:49-64.

9 Dyck PJ, Thomas OK. Diabetic Neuropathy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999.

10 Moberg E. Methods for examining sensibility of the hand. In: Flynn J, editor. Hand Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1975:295-304.

11 Patel MR, Bassini L. A comparison of five tests for determining hand sensibility. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1999;15:523-526.

12 Suarez GA, Dyck PJ. Quantitative sensory assessment. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Dellon AL, editors. Evaluation of Sensibility and Re-education of Sensation in the Hand. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1981:1-263.

13 Hoffman P, Buck-Gramcko D, Lubahn JD. The Hoffmann-Tinel sign. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:800-805.

14 Vargas Busquets MA. Historical commentary: the wrist flexion test (Phalen sign). J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:521.

15 Pang D, Wessel HB. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:105-121.

16 Lwu S, Midha R. Clinical examination of brachial and pelvic plexus tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(6):E5.

17 Ghobrial IM, Buadi F, Spinner RJ, et al. High-dose intravenous methotrexate followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as a potentially effective therapy for neurolymphomatosis. Cancer. 2004;100:2403-2407.

18 Ferner RE, Golding JF, Smith M, et al. [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) as a diagnostic tool for neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs): a long-term clinical study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:390-394.

19 Murji A, Redett RJ, Hawkins CE, et al. The role of intraoperative frozen section histology in obstetrical brachial plexus reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24:203-209.