Chapter 8 Periorbital Rejuvenation

Summary

Introduction

Ernst Fuchs coined the term blepharochalasia in 1896.1 The term is used now for idiopathic recurrent swelling, although Fox first used the term dermatochalasis over 50 years later. In the 19th century, the correction of ptosis was performed by resecting skin. William Bowman first described both anterior and posterior approaches.2 The first cosmetic surgery article was written by Charles Conrad Miller on the excision of ‘bag like folds of skin of the eyelid’.3 He went on to describe a subciliary incision as well as a supratarsal fold incision. The first cosmetic surgery text was published in 1907 by the same author.4 This new area of modern medicine was not as well accepted as the second book of cosmetic surgery by Frederick Strange Kolle.5 Kolle described the importance of marking the amount of skin to be excised preoperatively. A transconjunctival approach was first described by Julien Bourget along with the first pre- and postoperative photographs.6 The transconjunctival approach lost favor but regained popularity when Tessier used the same approach for access to the orbital floor.7 The retroseptal approach was introduced by Baylis and Sutcliffe in 1983.

The distinct fat compartments of the upper lid were first described by Bourget, but Salvadore Castanares described their relation to each other as well as the lower-lid fat pads.8 The importance of lacrimal gland prolapse was noted by Smith and Petrelli.9 Naugle realized the importance of lower-lid tightening in blepharoplasty.10 Multiple authors, including Rees, Flowers, Furnas, Aston, Skoog, and Sheen, have further advanced the art of blepharoplasty surgery. Hamra noted that correction of the periocular area extends to the lower face and includes redraping of the orbital fat with elevation of the SOOF and midface.11

Patient Evaluation

It is important to understand the patient’s concerns and to develop a complete plan of correction. The periocular area is complex anatomically and may have been affected by concomitant changes in several areas such as eyebrow ptosis, eyelid ptosis and/or midfacial descent. Dermatochalasis refers to the redundancy of eyelid skin. This is often associated with orbital fat protrusion or prolapse. Fat protrusion is more common in older individuals, but may be present in younger people with a familial predisposition. Significant dermatochalasis of the upper eyelids can lead to a heavy feeling around the eyes, brow ache, complaints of eyelashes being present in the visual axis, and reduction in the superior visual field.

It is important that complaints regarding lower eyelid bags and wrinkles are addressed. Candidates for lower blepharoplasty, especially those who smoke, occasionally exhibit bags over the malar area. The area of concern to the patient may prove to be the malar bags (Fig. 8.1) rather than the lower-lid fat pads themselves. When patients refer to their eyelid wrinkles, it is important to determine whether they are referring to the eyelid wrinkles that are present without animation (static wrinkles) or the wrinkles that become discernible when the patient is squinting or smiling. The surgeon must explain that the dynamic lines may not completely disappear after blepharoplasty. Static fine wrinkles may be addressed with laser or chemical resurfacing.

A history of dry eyes12 is an important factor in proceeding with blepharoplasty surgery. Other history and findings include Graves’ disease, diabetes, bleeding tendencies, hypothyroidism, renal dysfunctions, cardiovascular disorders, and hepatic dysfunctions. Lagophthalmos may be worsened after surgery and could result in corneal breakdown and infection if not detected during the clinical evaluation. Lagophthalmos may be caused by a seventh nerve palsy or lid retraction from trauma, surgery or midfacial descent. Other corneal diseases such as neurotrophic keratopathy are contraindications for eyelid surgery. This condition results in poor corneal wound healing and is caused by many diseases such as cerebrovascular accidents, multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, herpes simplex and herpes zoster infections. Previous eyelid surgery, eyelid trauma, eye or eyelid inflammation and allergies are also pertinent to the impending surgery.

Blepharochalasis or dermatochalasis may be present, and it is crucial that the two are differentiated from one another. The former is a rare bilateral condition most commonly seen in younger women. These patients have thin, atrophic, ‘crepe-paper-like’ wrinkled skin loosely bound to the orbicularis muscle. Blepharochalasis is more prevalent on the upper eyelids, resulting in protrusion of the orbital fat because of a weakened septum. This condition can be familial, although some believe episodes of recurrent angioneurotic edema may contribute to its development. Prominent eyelid vascularity may be associated with this condition.13 Dermatochalasis is a common bilateral condition affecting both genders equally. It is generally seen in middle or older age groups, presenting as a horizontal redundancy of the skin along with herniation of intraorbital fat caused by aging. Other conditions include blepharopachynsis (thickening of the eyelid) and blepharomelasma.14

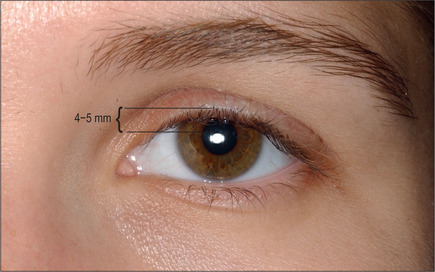

In straight gaze, the upper eyelid margin overlaps the limbus 1-2 mm.15 This overlap is increased on a patient with blepharoptosis. Since the full cephalocaudal diameter of the limbus is approximately 11 mm and a 1-2 mm overlap of the limbus is considered normal, any decrease in the visible portion of the limbus is a reflection of eyelid ptosis expressed in millimeters. For example, if only 7 mm of the iris is visible, the patient has 1-2 mm ptosis. A more accurate value is the margin reflex distance (MRD). This measurement is from the central corneal light reflex to the upper eyelid margin. The normal measurement is 4-5 mm (Fig. 8.2).

The examiner can obtain an accurate measurement of levator function (excursion) by holding a ruler next to the patient’s eyes. With the head immobilized, the patient is instructed to look downward, and the point corresponding to the eyelid is noted on the ruler. The patient is then instructed to look upward, and the corresponding point is again checked on the ruler. The distance between these two points reflects the levator function expressed in millimeters. It is often necessary to repeat this test several times to obtain a reliable number. Normal eyelid excursion is 15 mm or more. Excursion of 4 mm or less is considered poor levator function, 5-7 is fair, 8-10 is good and 10-15 is excellent. In general, patients with aponeurotic ptosis have good-to-excellent levator function and those with congenital ptosis have poor levator function. The position of the eyelid crease serves as a guide for the degree of ptosis and potential for levator dehiscence. A higher than normal upper eyelid crease (8-10 mm) may be a sign of levator dehiscence and aponeurotic ptosis. Common causes of neurogenic ptosis include myasthenia gravis, Horner’s syndrome and third nerve palsies. An example of a myogenic-type ptosis is myotonic dystrophy. Pseudoptosis may be caused by aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve with overactive orbicularis tone or may be present with contralateral lid retraction.

Excess fullness in the lateral portion of the upper eyelid, particularly in older patients, could denote prolapse of the lacrimal gland or an extension of the lateral (temporal) eyelid fat pad. Occasionally a significant degree of fullness is found in the lateral portion of the upper eyelid as a consequence of a prominent lateral supraorbital rim or excess retroorbicularis oculi fat (ROOF).16 The lower eyelid usually touches the lowest portion of the limbus. Generally, any scleral show is considered undesirable and may serve as a risk factor when removal of excess skin from the lower eyelids is planned. In this case the surgeon must either strengthen the lower-lid support mechanism or be extremely conservative with the skin removal. The fat pads in the medial, central, and lateral compartments of the lower eyelids are examined while the patient gazes straight ahead and upward. A depression above the infraorbital rim (malar groove) or nasojugal area should be assessed; correction of this condition will enhance the blepharoplasty results. Aesthetic surgery patients commonly exhibit hyperpigmentation of the lower eyelids and less commonly of the upper eyelids.

Slow, incomplete blinking may denote a weakness of the orbicularis muscle. Normal spontaneous blinking frequency is 10-15 blinks every minute, with the lower eyelid movement starting two-tenths of a second earlier than the upper eyelid.15

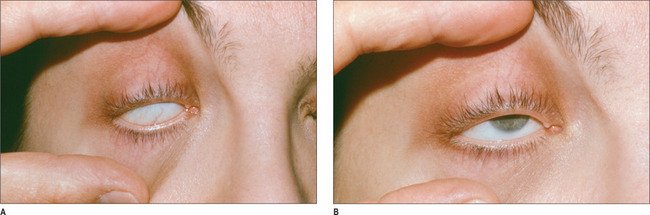

A negative Bell’s phenomenon is an indicator of potential for exposure keratitis postoperatively. The patient is asked to close his or her eyes while the examiner forcefully holds the eyelid open (Fig. 8.3). Normally, the globe will rotate cephalad. The surgeon has to be conservative when planning blepharoplasty if Bell’s phenomenon is poor or nonexistent.

The most projected portion of the malar soft tissue on the profile view should line up with the most projected point of the eye globe or project more anterior to it. Deficiency of the malar soft-tissue prominence (negative vector) creates a negative value and is a significant risk factor for dry eye syndrome or postoperative lid lag.12

A gross visual examination with a vision chart may disclose an abnormality of which even the patient is unaware. This abnormality could range from minimal to significant visual loss. A visual field examination may indicate a deficit in the visual field by a true ptosis of the eyelids or pseudoptosis related to dermatochalasia. The basic secretion test (basic Schirmer’s test) can be used to measure the amount of basal tear secretion without the overlying and less predictive reflex tearing arc. Topical ophthalmic anesthetic is placed in both eyes. The fornices are gently swept with a cotton-tip applicator. A 5 × 35 mm strip of Whatman No. 41 filter paper is folded 5 mm and placed on the lateral third of the lower-lid conjunctiva. While the patient closes the eyes, the strips of the paper are left in place for 5 minutes. Generally, wetting of the strips less than 10 mm from the fold is considered positive for some degree of dryness. This test can be variable in different patients and in the same individual at different times; therefore, it cannot always be fully relied upon. A tear break-apart time is a more reliable test for documentation of the dryness of the eyes. If there are questions concerning the amount of tear production or the eye condition, it is always prudent to secure an ophthalmologic consultation.

Further testing for a patient with eyelid ptosis includes the phenylephrine test. This test is contraindicated with a history of narrow angle glaucoma, labile hypertension or a shallow anterior chamber on examination. Phenylephrine may exacerbate increased intraocular pressure in a susceptible patient. This test is performed for consideration of a Müller muscle – conjunctival resection (Putterman procedure). First, the margin reflex distance is measured bilaterally. Topical phenylephrine 2.5% or 10% solution is then placed in the superior cul-de-sac while the patient is in a reclined position.17 Several minutes are allowed to pass and the margin reflex distance is re-measured with the patient in a sitting position. The eyelid height attained with the installation of topical phenylephrine can be achieved with an 8 mm Müller muscle conjunctival resection. Levator advancement surgery can be considered in patients with a negative phenylephrine test and normal levator function.

Operative Approach

Anatomy

The supratarsal crease is located 8–10 mm above the upper lid margin. This crease is formed by adhesion of the orbicularis muscle and fi brous attachments of the levator aponeurosis to the skin. A supratarsal fold that is too high or appears to be nonexistent suggests attenuated, split, or even absent levator attachment to the skin. A male skin crease is usually 6–8 mm and a female skin crease is 8–10 mm above the lid margin.18 A vast variation in the amount of skin present exists between individuals of various races, ages and ethnic descents. Those from the Far East have an absent supratarsal fold even with normal levator function. This results from either a lack of aponeurotic attachments to the skin or attachment at a site much lower than normal.

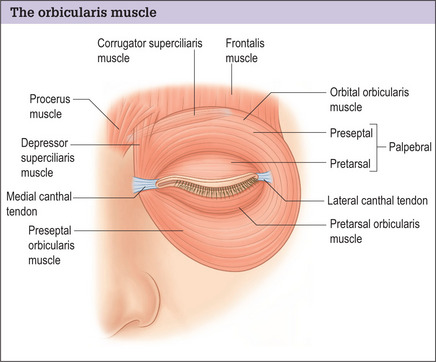

The orbicularis muscle has two segments concentrically distributed around the eye, the orbital, and palpebral portions (Fig. 8.4). The orbital segment of the muscle overlies the orbital rims. This muscle originates from the superomedial border of the orbital wall and the maxillary process of the frontal bone. The most cephalic portions of the fibers spread upward onto the forehead to interface with the frontalis and corrugator supercilii muscles superiorly and continue laterally to overlie the anterior surface of the temporalis fascia. There are additional fibrous attachments to the medial canthal tendon and the frontal process of the maxilla, as well as the inferior orbital rim. In the lower lids the orbital portion of the orbicularis facilitates the forceful closure of the eyelid during squinting and acts in concert with other mimetic muscles during animation.

The palpebral portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle is further divided into preseptal and pretarsal segments. The preseptal segment extends from the medial canthal tendon to the lateral raphe overlying the lateral canthal tendon. It has superficial origins from the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon. The deep heads of the muscle, originating from the lacrimal fascia overlying the lacrimal sac, contribute to the lacrimal pump mechanism.19

The pretarsal segment of the orbicularis oculi muscle arises from the superficial heads at the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon and from deep heads originating along the posterior lacrimal crest and the lacrimal fascia (Horner’s tensor tarsi muscle). The pretarsal muscle segments from both the upper and lower eyelids fuse laterally, forming the lateral canthal tendon that inserts onto the periorbital at Whitnall’s orbital tubercle.

The medial canthal tendon is composed of two heads. The more prominent superficial head attaches to the anterior lacrimal crest, whereas Horner’s muscle, the smaller, deeper head, attaches to the posterior lacrimal crest. The canaliculi are positioned just beneath the superficial head of the medial canthal tendon.15 A portion of the orbicularis muscle, known as the muscle of Riolan, which is the smallest striated muscle in the body, is situated at the lid border. The nerve supply to the orbicularis is via the seventh cranial nerve. These nerve fibers course within the posterior fascia of the muscle and enter through its deep side.20

The orbital septum is a thin sheet of fibrous tissue that lies deep to the preseptal portion of the orbicularis muscle. It serves as a protective barrier and impedes the spread of hemorrhage, infection or inflammation to the orbit. The orbital septum also restricts protrusion of the orbital fat. It extends from the arcus marginalis of the orbital rims, a confluence of the facial bone periosteum and the periorbita, to the tarsal borders. In the occidental upper eyelid, the orbital septum fuses with the levator aponeurosis approximately 2-3 mm above the upper border of tarsus.15 Once fused, the fibers pass downward to insert on the lower anterior surface of the tarsus. In the lower eyelid the orbital septum attaches directly to the inferior border of the tarsus with the capsulopalpebral fascia.21

A layer of fat between the orbicularis muscle and periosteum spans over the lateral half of the orbital rim and sometimes results in protrusion, necessitating its removal. This is termed the retro orbicularis oculi fat pad. There is a similar structure in the lower eyelid termed the suborbicularis oculi fat pad.22,23 The preaponeurotic orbital fat is another distinct layer situated between the levator muscle and the orbital septum of the upper eyelid. Two pockets of fat can be found in the upper eyelid and three in the lower eyelid.

The levator palpebrae muscle is the principal retractor of the upper eyelid. It originates from the periorbita overlapping the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone just above Zinn’s artery and traverses the orbital roof, extending anteriorly over the superior rectus muscle. The levator aponeurosis divides into two attachments approximately 10-12 mm proximal to the tarsal plate.24,25 The anterior aponeurotic fibers attach to the orbital septum at a variable distance above the tarsal border. The posterior fibers of the levator aponeurosis extend caudally to insert into the anterior surface of the tarsus 3-4 mm below its superior border. The levator aponeurosis possesses medial and lateral extensions designated as the horns. The lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis courses through the lacrimal gland, dividing it into orbital and palpebral lobes to attach to the superior edge of the lateral canthal tendon at the lateral retinaculum. The medial horn, which is not as thick as the lateral horn, passes over the sheath of the superior oblique tendon, fusing with the upper border of the posterior limbs of the medial canthal tendon and fibers of the orbital septum.

The superior sheath of the levator muscle condenses at the level of the equator of the globe to form the superior transverse ligament of Whitnall, a check ligament. It attaches medially to the trochlea of the superior oblique muscle, extending laterally to insert onto the capsule of the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland. Whitnall’s ligament functions as a pulley to facilitate the change in the direction of the levator action from horizontal to vertical.26

The overall length of the levator muscle and its aponeurosis is approximately 55 mm. The muscular portion constitutes about 40 mm of the total length, and the tendinous portion measures 15 mm.15 The levator complex derives its innervation from the superior ramus of the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III).

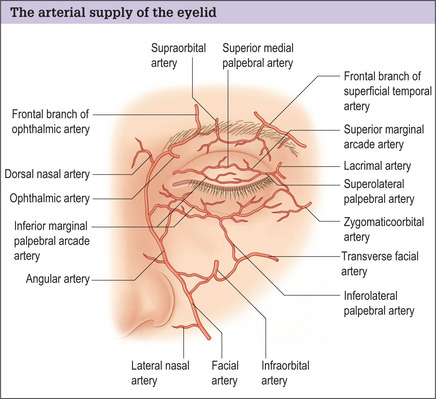

The principal blood supply to the eyelids is derived from the ophthalmic branch of the internal carotid artery and is supplemented by abundant collateral circulation from the facial branches of the external carotid artery. The medial superior palpebral artery joins with a branch of the angular artery (a branch of the external carotid artery), extending a few millimeters beyond the anastomosis, and divides into upper and lower branches (Fig. 8.5). The upper branch courses along the upper border of the tarsus as the superior palpebral arcade and superior marginal arcade. The lower branch runs along the anterior surface of the tarsus at the lid margin. These branches are joined by branches of both the internal carotid (lacrimal, zygomaticofacial and infraorbital) and external carotid (superficial temporal artery). The marginal arcades run along the anterior border of tarsus near the lid margins and the superior peripheral arcade courses along the superior border of tarsus.

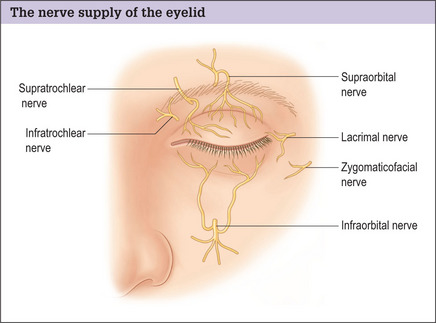

The sensory innervation to the upper eyelid is supplied primarily through the branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve divides into the lacrimal, frontal and nasociliary branches. The lateral palpebral branch of the lacrimal nerve supplies the sensory innervation to the superior lateral portion of the upper eyelid (Fig. 8.6).

The frontal nerve passes through the superior orbital fissure and courses cephalad to the levator muscle, where it divides into a larger supraorbital branch and a smaller supratrochlear branch. The supratrochlear nerve provides sensory fibers to the medial portion of the upper eyelid. The infratrochlear nerve, a branch of the nasociliary nerve, also provides sensory fibers to the medial aspect of the upper eyelid (Fig. 8.6). This nerve must be blocked completely to ensure a comfortable resection of the medial fat pads.

The lacrimal secretory system is composed of basic and reflex secretors. The basic secretors include the accessory lacrimal glands of Krause and Wolfring, the mucin-secreting goblet cells, and the meibomian glands.24 There are approximately 20 to 40 glands of Krause located in the upper fornix and six to eight glands situated in the lower fornix. Far fewer glands of Wolfring exist in comparison, with three located at the superior tarsal border of the upper eyelid and one at the inferior tarsal border of the lower lid. The secretions drain directly onto the conjunctival surface. Approximately 20 to 25 meibomian glands exist in the upper and lower eyelids, and are positioned vertically within the tarsal plate. Smaller contributions to the lid secretion are provided by the glands of Zeis (sebaceous) and Moll (apocrine), which are intimately associated with the cilia of the eyelids.

The tear film has three layers, of which the innermost layer overlying the surface of the cornea is composed of a mucopolysaccharide substance secreted by the conjunctiva goblet cells.27 This is the thinnest layer of the tear film. The intermediate aqueous layer is produced by secretions from the accessory lacrimal exocrine glands of Krause and Wolfring. This layer, which is 98% water, represents close to 90% of the precorneal tear film thickness. The outermost layer of the tear film is primarily composed of secretions from the lipid producing meibomian glands. This layer is important in stabilizing the precorneal tears and reducing evaporative losses of the underlying layers.

Upper lid blepharoplasty

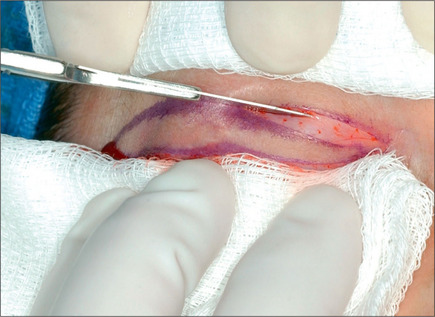

The caudal or eyelid crease incision on the upper eyelid is marked first (Fig. 8.7). This incision is made either precisely at the crease on younger patients or 1 mm caudal to the existing crease on older patients. This incision line will rise slightly during the wound-healing phases. It is important to gently stretch the skin while designing the incision otherwise the incision may ride too high postoperatively. The excess skin is pinched with a pair of fine, smooth forceps, and the amount of skin to be removed is assessed. The cephalad incision line is then marked (Fig. 8.8A). These incision lines are checked while the patient is in a sitting position. While the eyelids are closed, the skin is pinched gently again, using a pair of smooth forceps, with the patient in a supine position (Fig. 8.8B). The maximum amount of skin that can be excised before the eyelid opens up is estimated. The upper lid incision marking is then extended laterally and medially with a cephalic curve at both ends. Next, the fat pads are examined in all of the compartments and marked.

Fig. 8.7 The caudal portion of the upper eyelid incision is at the eyelid crease or slightly caudal to it.

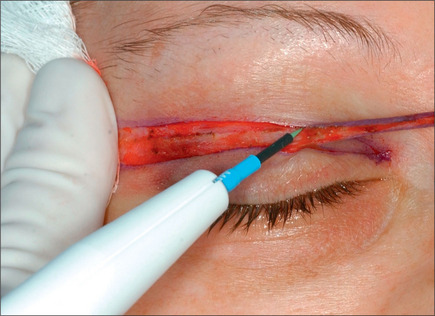

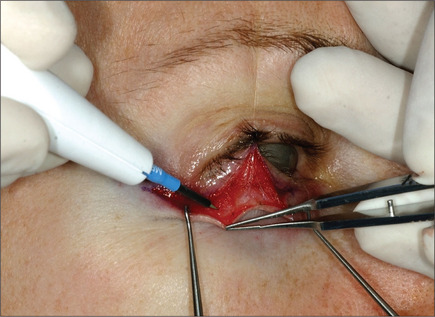

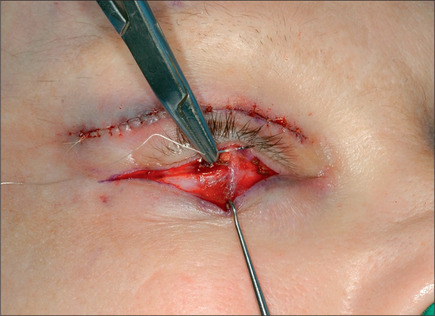

While the patient is in a supine position, the face is prepped and draped in the usual manner, using saline and povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution. The incision markings are freshened if necessary. The anesthetist or anesthesiologist will then administer intravenous sedation using a combination of propofol, fentanyl and midazolam. Usually, patients are instructed to take 10 mg of diazepam (Valium) the night before surgery and 10 mg the morning of surgery. After adequate sedation has been achieved, the patient’s eyelids are infiltrated using lidocaine hydrochloride containing 1 : 100 000 epinephrine and 3 units/mL of hyaluronidase. The upper eyelid surgery is commenced after adequate time has elapsed to allow the epinephrine to provide the maximum vasoconstriction (usually 10 minutes). The assistant retracts the tarsal portion of the eyelid using a folded sponge while the surgeon pulls the eyelid cephalically with a similar piece of gauze. The incision closest to the eyelid margin is made and taken through the skin (Fig. 8.9). If a portion of the orbicularis muscle is to be removed, which commonly is not the case, it may be included in the incision; otherwise the orbicularis incision is avoided to minimize the chance of injury to the levator aponeurosis. The assistant then advances the sponge closer to the cephalic incision as the surgeon retracts the lid cephalad to the incision (Fig. 8.10). This retraction and counter traction facilitates precise placement of the incision and avoids any irregularities. The incision is curved cephalad at the lateral end to avoid the potential for creation of an epicanthal fold as a result of scar contracture. The skin is then excised starting laterally, using a fine needle tip cautery, while the assistant is pulling the skin over the lateral canthal area laterally and extended laterally (Fig. 8.11). Care is taken to stay in the correct plane between the skin and orbicularis. A small double skin hook is placed in the cephalic portion of the incision and another one in the caudal portion, separating the incisions. Hemostasis is then achieved using a pair of fine forceps and cautery.

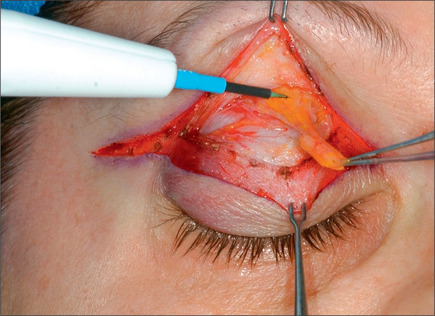

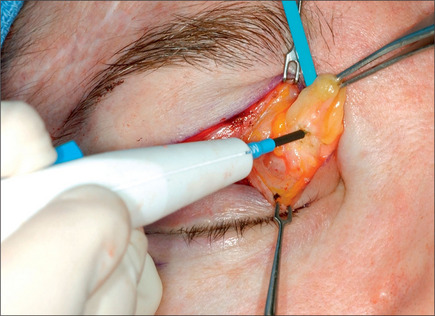

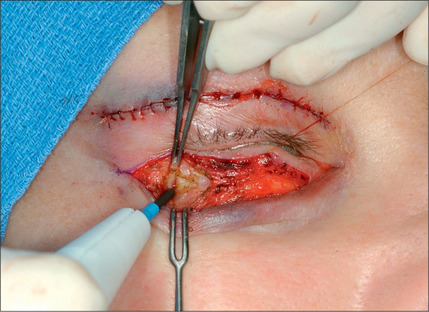

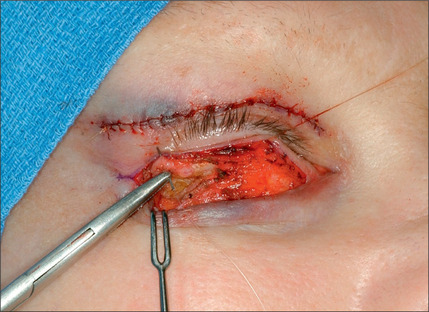

After meticulous and complete hemostasis, the orbital septum is incised superiorly and the preaponeurotic fat is exposed only if its removal is indicated. The temporal fat pad is seldom removed. Almost invariably there is an extension of the temporal fat pad laterally,28 although it is not always necessary to expose this fat to remove it. While exerting gentle traction, the surgeon can readily deliver the fat. A small vessel that is a branch of the lacrimal artery joining the fat pads can be observed at this point. This vessel must be cauterized before transection of the lateral extension of the temporal fat; otherwise brisk bleeding may occur. The fat is then removed using the fine needle cautery (Fig. 8.12). With blunt dissection using a fine hemostat, the medial fat pad is exposed, pulled anteriorly, and injected with lidocaine hydrochloride. This not only eliminates potential patient discomfort, but also minimizes the chance of oculocardiac reflex,29 which is a common occurrence during this portion of a blepharoplasty. The medial fat pad is then removed in a similar manner (Fig. 8.13). Conservatism in removing the fat pads prevails. Overzealous removal of the temporal fat will result in a significant change in the shape of the eyelids and an undesirable hollowing of the upper eyelid. This may create an exaggerated deepening of the supratarsal fold and should be avoided. The lacrimal gland is explored by applying gentle pressure on the globe, and if it protrudes beyond the orbital rim, it should be suspended.30 To do this, the surgeon carefully frees the protruding portion of the gland and the gland is then anchored to the periorbita, incorporating the gland capsule using a 6-0 non-absorbable suture. The suture, after being passed through the gland capsule and the periorbita, is gently tied while the gland is being reduced in position by the assistant. A second or third suture is placed if mandated by the extent of the gland ptosis.

Rarely, some patients exhibit prominence in the lateral portion of the upper eyelid as a result of excess fat between the orbicularis oculi muscle or the lateral portion of the supraorbital rim (ROOF). This fat overlies the periosteum and extends from the middle portion of the upper eyelid to the area past the level of the lateral canthus. The excess fat can be removed by retracting the orbicularis oculi muscle anteriorly and dissecting between the orbicularis muscle and the fat. The excess fat overlying the orbital rim is then removed using the coagulation power of the cautery. Electrocoagulation may abate the postoperative bleeding and ecchymosis. Should the projection of the lateral supraorbital rim be excessive, the periosteum is incised parallel to the rim and elevated using a periosteal elevator. The bone is then removed gently using an oval burr. The periosteum is repaired to provide a gliding surface for the orbicularis oculi muscle. To repair the upper lid skin incision, the surgeon places a simple stitch at the level of the pupil, using 6-0 plain, fast-absorbable catgut sutures unless the patient is allergic to catgut (Fig. 8.14). A second stitch is then placed at the level of the lateral canthus. The portion between the medial end of the incision and the lateral canthus is repaired using 6-0 plain catgut subcuticular sutures. The remaining portion of the incision lateral to the canthus is repaired with running locked suture (Fig. 8.15). If a canthoplasty is part of the surgical plan, the lateral portion of the incision is closed after completion of lower-lid surgery and canthoplasty. The procedure is completed in the same manner for the opposite upper eyelid.

Skin/muscle lower blepharoplasty

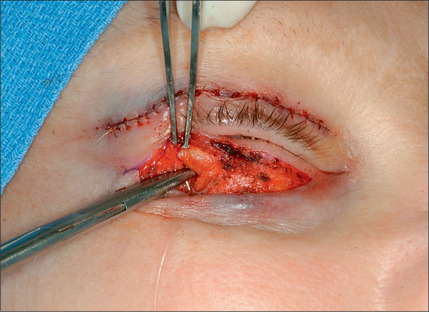

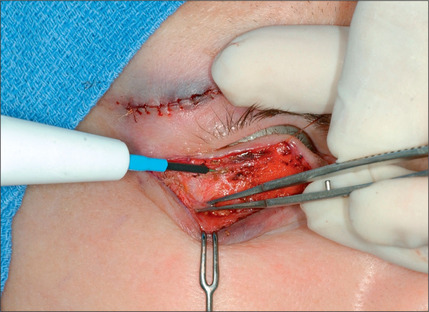

The lower eyelid is retracted, pinched and released once more prior to surgery so that proper eyelid tone can be assessed. The skin of the lower eyelid is gently pulled down, and if removal of any excess skin is planned, the eyelid is observed to determine the amount of caudal stretch of the eyelid skin that results in retraction of the lid margin and increase in scleral show. Conservative removal of skin from the lower eyelids is crucial to reduce the potential problems. The protruding fat pads are then marked. A lower eyelid skin crease incision is marked 1-2 mm caudal to the eyelashes above. This mark does not extend medial to the punctum. Protective eye shields are placed into position. Local anesthesia and preparation of the surgical field is performed as described for the upper eyelid. A small incision is made laterally at the level of the orbital commissure using a #15 blade (Fig. 8.16). This incision is continued through the skin crease closest to the lid margin (1-2 mm below the eyelashes) using a pair of straight iris scissors. Next, a small double skin hook or suture is placed on either side of the incision, retracting it cephalically and caudally. At this point, the skin incision in the crease closest to the eyelashes is continued medially, stopping short of the lower punctum (Fig. 8.17). A retraction suture is placed at the tarsal side of this incision retracted cephalad to the lid (Fig. 8.18). Using a pair of baby Metzenbaum or fine needle cautery, dissection is continued caudally in a preseptal plane to the orbital rim (Fig. 8.19). Care is used to leave the pretarsal orbicularis intact. At this point, dissection is deepened by incising the orbital septum to expose the fat in all three compartments. Injection of a small amount of local anesthetic in the medial fat pad will curtail patient discomfort as will an injection of local anesthetic in the lateral compartment. The excess fat is conservatively removed from these compartments employing careful dissection, retraction, and use of fine tip cautery for transection of the fat (Fig. 8.20). Care is taken not to retract the fat too vigorously as this may rupture deep orbital vessels.

Fig. 8.17 A subcilliar incision, stopping short of the punctum, is made with a pair of sharp iris scissors.

Fig. 8.18 A retraction suture is placed at the tarsal side of the incision and it is retracted cephalad.

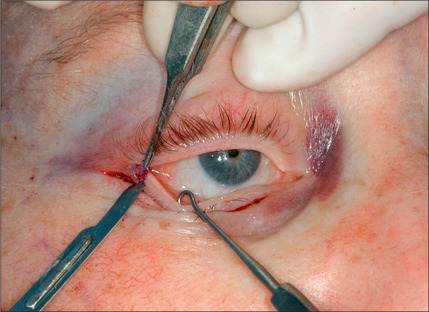

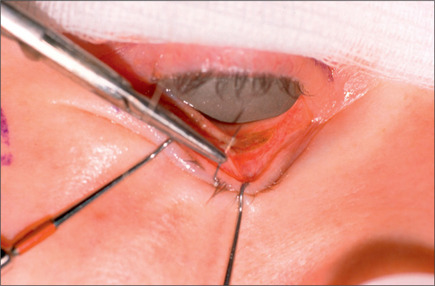

Commonly, a canthopexy is performed in the following manner. If a skin muscle flap is being used, the lower lid retractors are released close to the lateral canthus (Fig. 8.21). If a skin flap blepharoplasty is being done, a small incision is made in the orbicularis muscle immediately caudal to the tarsal plate about 5-6 mm in length, almost 3 mm medial and 3 mm lateral to lateral commissure (Fig. 8.22). The incision is deepened and all of the retractors are released to render the lateral commissure freely mobile. A 5-0 nylon suture is passed through the lateral commissure to include the lateral canthus avoiding penetration of the conjunctiva (Fig. 8.23) passed through the periorbita at the level of the mid pupil, posterior to the lateral orbital rim and tied incrementally, watching the lateral canthus rise and the lower lid margin is pulled posteriorly and laterally against the globe (Fig. 8.24). The lid tightness is tested by retracting it with a pair of fine forceps. One should be able to separate the lid from the globe only 3-4 mm intraoperatively. It is important to ensure that the lid margin, thus the eyelashes, would not rotate externally or internally. There also should be no space between the lid and the globe, and there should be no lateral redundancy of the tarsal plate causing a small kink. If this is noted, a small (2-3 mm) wedge excision of the lower-lid margin, very close to the lateral canthus will correct the problem (Fig. 8.25). The resultant defect is repaired using 6-0 Monocryl for the tarsal plate and 6-0 fast absorbable catgut for the skin and orbicularis (Fig. 8.26).

Fig. 8.21 If a skin muscle flap is being used, the retractors are released close to the lateral canthus.

Fig. 8.26 The resultant defect is repaired using 6-0 Monocryl and 6-0 fast absorbable catgut systems.

For patients who exhibit significant weakness of the lid support mechanism as documented by the pinch and traction test, a canthoplasty will be performed before the excision of skin and repair of the lateral portion of the upper eyelid skin, if an upper eyelid blepharoplasty is planned concurrently.32 Prior to making the incision, the current position of the lateral canthus is marked on the bone using brilliant green to the periosteum with a 25 gauge needle. The incision is then deepened to the periosteum. A tattoo mark is transferred to the bone with a bone pencil. A subperiosteal dissection is conducted toward the lateral canthus by retracting the soft tissue. The periosteum is elevated under the lateral canthus and gentle dissection deeper into the orbit will expose the lateral retinacular ligament. The entire ligament is dissected and detached until adequate mobility of the lateral canthus is accomplished. Additionally, the lower-lid retractors are released with a needle cautery. A double armed 5-0 Mersiline suture is passed through and looped around the ligament. Considering the previously marked lateral canthus and the degree of cephalic repositioning and tightening necessary, the surgeon selects the new location for the attachment of the retinacular ligament. Two burr holes are made on the lateral orbital wall while the orbital contents are protected with a malleable retractor. The needles attached to the ligament are then passed through the holes and tied over the lateral orbital wall. The degree of the tightness and amount of lid transposition are judged based on the preoperative and intraoperative findings. The lid should be tight enough to prevent its separation from the globe beyond 3-4 mm with manual lift, and it should overlap the iris 1-2 mm in a straight gaze. When a lower blepharoplasty is intended through a conjunctival incision, it is performed before tightening the retinacular ligament suture to avoid limitation of the exposure.

At this point, the lower eyelid flap is draped back. To estimate the safe amount of skin to be removed, the surgeon pulls the skin over the malar area caudally to simulate the gravity effect. The assistant’s finger then replaces the surgeon’s finger. While this transaction is taking place, the surgeon watches to assure that the skin of the malar area does not move cephalically. While the lid margin remains in a neutral position with the patient gazing straight ahead, the excess skin is assessed and excised, including the orbicularis muscle (Fig. 8.27).

If the patient possesses hyperactive orbicularis muscles, an additional amount of lower-lid muscle is excised from the skin muscle flap cephalically in a beveled fashion. Because a strip of the muscle of Riolan is always maintained anterior to the lower-lid tarsal plate, beveling of the lower orbicularis will ensure a smoothly contoured lower eyelid. After resecting the orbicularis muscle, the surgeon very gently wipes the remaining portion of the orbicularis with a Weck-cel(tm) sponge. This facilitates detection of small vessels that may bleed postoperatively when the vasoconstrictive effect ceases. Any bleeding vessel is gently cauterized. The lid is then redraped and lined up properly. The maneuver that was used to assess the amount of excess skin removal is repeated, this time with the skin of the lid in position. Presence of excess skin while the malar skin is being pulled to mimic the effect of gravity indicates that additional skin should be excised. The authors have used these techniques in more than 2000 pairs of eyelid surgeries with high degree of success. The orbicularis muscle is then sutured to the periosteum at the lateral canthus area using 6-0 Monocryl. Interrupted, fast-absorbable sutures are placed laterally, and the remaining portion of the lid incision is repaired using 6-0 plain catgut running subcuticular sutures (Fig. 8.28). It is crucial that deeper bites be taken on the ciliary side compared with the flap side to avoid overlapping of the skin margin. It is necessary not to take a back bite in order to avoid a purse-string effect. No attempt should be made to eliminate all of the wrinkles visible when the patient is in the supine position; otherwise as gravity pulls the lid and malar soft tissues caudally when the patient assumes a sitting position, lower-lid retraction will ensue. A Frost suture is used routinely for 24 hours. If the patient exhibits significant hyperpigmentation, the lower lid can be treated with one pass of CO2 laser set at 100 mJ (newer lasers), density of 4, 60 watts. Occlusive dressing like Laser Seal or Flexxon is applied. After completion of this part of the surgery a temporary tarsorrhaphy is done using 6-0 plain catgut and a Frost suture is placed. Steri-Strips (1/4 inch) are applied over the free ends of the eyelid subcuticular sutures laterally. Throughout the operation, the eye is irrigated using balanced salt solution if an eye shield is not used. Ophthalmic ointment is applied routinely. The incisions are then covered with an ophthalmic Bacitracin ointment, and the patient is transferred to the recovery room.

Transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty

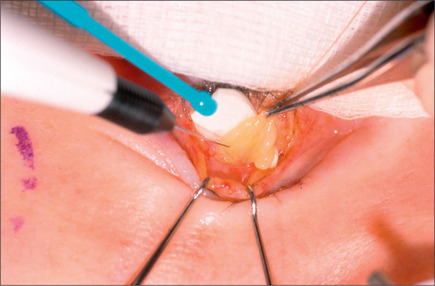

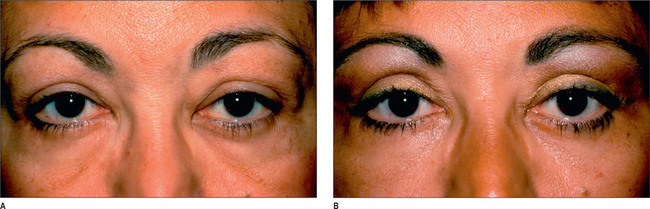

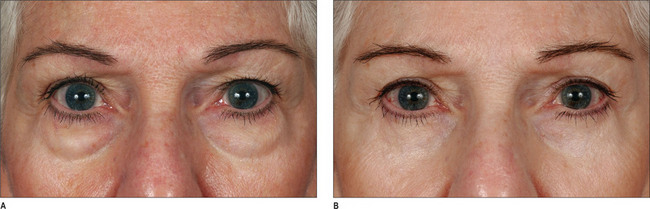

Should a transconjunctival33–36 approach be selected, a protective eye shield is inserted. Following injection of lidocaine containing 1 : 100 000 epinephrine and retraction of lid margin with two single skin hooks, pressure is applied on the eye globe and a bulge in the lower fornix is noted (Fig. 8.29). An incision is made caudal to the vascular arcade using the fine needle electrocautery, incorporating the conjunctiva deep in the fornix and Müller muscle. Careful dissection readily exposes the medial fat pad. To reach the medial and lateral fat pads, the surgeon must often use two small Crile right angle retractors or Desmarres retractors (Fig. 8.30). The lateral fat pad is often cephalad and lateral to the central fat pad. Careful dissection and judicious removal are necessary to achieve an optimal result. Periodic pressure on the globe may help the surgeon judge the amount of fat to be removed. The lid is allowed to assume a normal position and its contour is observed. Minimal depression along the infraorbital rim is optimal. This depression, however, should disappear as gentle pressure is applied to the lid. One or two 6-0 plain sutures are used to repair the incision (Fig. 8.31). This procedure commonly results in natural-appearing lid rejuvenation (Figs 8.32 & 8.33).

Lower blepharoplasty using skin-flap technique

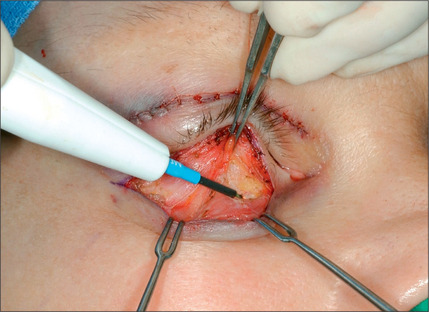

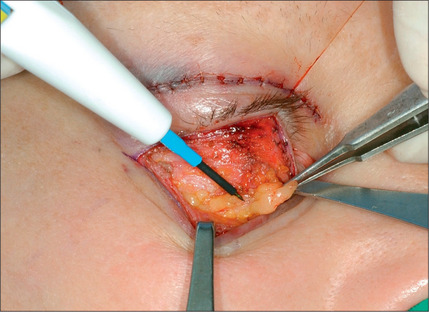

For the patients who exhibit significant wrinkling of the lower lid with thin skin, a skin flap with canthopexy may provide a better outcome. The incision is similar to the skin muscle flap technique, but the dissection will be conducted in the subcutaneous plane using either a pair of Metzenbaum scissors or a fine needle cautery with very low energy setting to avoid thermal damage (Fig. 8.34). The orbicularis muscle and the orbital septum are released at the level of orbital rim and protruding fat will be managed by removal, repositioning, or a combination of both, depending upon the patient’s needs. The orbicularis muscle is repaired using two 6-0 monocryl inverted sutures. Following canthopexy, through a small incision in the orbicularis laterally, as outlined previously, the skin is re-draped and the excess skin is excised using the principles discussed for skin muscle flap technique. The skin flap is tacked down to the orbicularis muscle in three or four sites using interrupted sutures of 6-0 fast absorbable catgut, oriented cephacaudally, to minimize the potential for collection of fluid under the skin (Fig. 8.35). This technique provides gratifying results on patients with significant skin redundancy.

Management of deep nasojugal or malar grooves

For patients who exhibit deep nasojugal or malar grooves, the fat pads are dissected, repositioned caudally, and fixed to the periosteum under the orbicularis muscle after release of the arcus marginalis.37,38 To accomplish this goal, the surgeon elevates the orbicularis oculi muscle and the orbital septum, leaving the periosteum intact. This dissection is continued medially up to the lateral nasal region. The lower-lid excess fat is then dissected; the excess portion, beyond what is needed, is excised, and the remaining fat is partially incised and rolled caudally. Using 6-0 Vicryl, the surgeon fixes the adipose flaps to the periosteum over the malar region. The fat also can be transected and repositioned as a graft, or more suitably the malar fat pad can be dissected, repositioned cephalically, and fixed to the infraorbital rim position using two 5-0 vicryl sutures. Both authors prefer the latter technique.

Laser resurfacing of the lower eyelid

In patients who undergo transconjunctival resection of the lower fat pads, or the patients who are candidates for a skin muscle flap, it may be necessary to resurface the lower lids with laser to improve the lines and hyperpigmentation.39 The senior author uses the carbon dioxide laser, set at 100 mJ, density of 5 and 60 watts. Usually, only one pass is made with minimal or no overlap. A second pass is rarely made using the same settings, except the density is reduced to 4 with no overlap on the transconjunctival blepharoplasty, but never on the skin muscle flap technique. The lid is covered with a silicone dressing (Laser Seal, Innovation Alley, Lyndhurst, Ohio).

Levator aponeurosis advancement operation

This procedure is technically demanding and requires practice to produce consistent results.40 The following description is a base to allow the reader to acquire further knowledge and skill. A novice ptosis surgeon who follows the guidelines in this chapter can achieve a good result, but an excellent result requires refinement and frequent adjustments to one’s technique. To attain proper height and prevent significant lagophthalmos, this procedure is typically performed under local anesthesia with minimal sedation to maximize patient cooperation. A standard upper-eyelid blepharoplasty approach is performed as described previously, if indicated. Otherwise, a shorter incision confined to the upper eyelid crease is sufficient. The skin is excised, if planned, and the septum is exposed. Caudal traction is placed on the inferior border of the incision with a micro two-pronged skin hook. Once the septum is identified, it is incised superiorly over the preaponeurotic fat pad. The fat pad is resected, if indicated, or retracted superiorly. The levator aponeurosis and muscle belly are identified. The location of the levator aponeurosis is noted. It is often disinserted from the anterior surface of the tarsus. The cephalic surface of the tarsus is then exposed by dissecting the levator aponeurosis off of the tarsus with a Westcott scissors. The Müller’s muscle is dissected off the posterior surface of the aponeurosis. Once adequate mobilization of the levator is achieved, the levator is advanced onto the anterior surface of the tarsus by suturing the aponeurosis to the anterior tarsus in a partial thickness, horizontal mattress fashion using a 6-0 nylon spatula needle. This suture is placed at the medial lid peak. The eyelid is everted and observed to insure that the suture is partial thickness. A temporary knot is tied. The patient is asked to open the eyes. The height and contour of the eyelid is assessed in a reclining position. If the height and contour are satisfactory, the suture is then permanently tied. The patient is then seated upright on an adjustable operating room table and the lid height is assessed as well as the amount of lagophthalmos. A small amount of lagophthalmos (<2 mm) may be present due to the effect of the lidocaine on the protractor of the eyelid, the orbicularis oculi muscle. An additional suture may be placed laterally or medially depending on the amount of ptosis and lid contour. The wound is closed in a fashion similar to a blepharoplasty procedure. Frequent lubrication of the eye and cold compress are used postoperatively as lagophthalmos is more prevalent after ptosis surgery.

Müller muscle-conjunctival resection

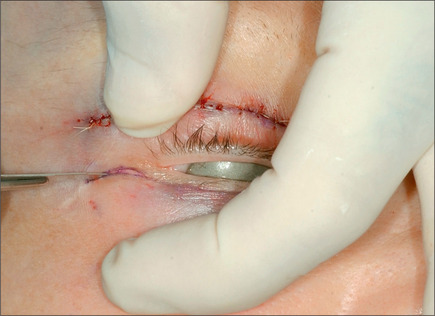

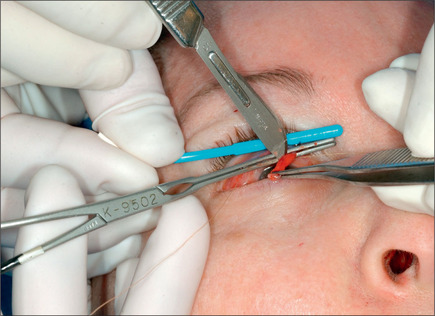

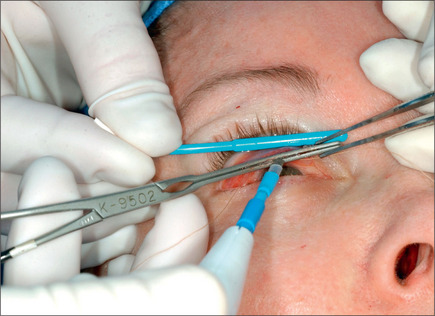

The Müller muscle-conjunctival resection procedure was described by Putterman and Urist in 197529,30 and modified by the senior author in 1989.31 This procedure may be used in patients with acquired 1-3 mm ptosis who demonstrate good response with elevation of the eyelid following instillation of topical 2.5% phenylephrine. If the response to the installation of neosynephrine is ideal by raising the lid to normal position 8 mm of Müller’s muscle and conjunctiva is removed. For a lesser response 9 mm is removed and for an exaggerated response 7 mm of this composite tissue is removed. This procedure is performed with the patient under local anesthesia with sedation. With the patient in the supine and sitting positions, the eyelid is marked. The lid is then infiltrated with xylocaine containing 1 : 100 000 epinephrine, avoiding injection in the Müller’s muscle. Next, the eyelid is everted; 7-9 mm of Müller’s muscle and conjunctiva is measured (Fig. 8.36). This will be a fold of composite tissue measuring 3.5-4.5 mm, depending on the response to neosynephrine. Next, a customdesigned non-crushing clamp (Kupp surgical ptosis clamp – #KS999 GP) is placed across the Müller’s muscle and conjunctiva without catching any portion of the tarsal plate. A 5-0 plain catgut doublearmed suture is then passed under the clamp in a horizontal running fashion. The muscle and conjunctiva above the clamp are then excised using a #10 blade (Fig. 8.37). Hemostasis is secured using a cautery (Fig. 8.38). The clamp is then removed (Fig. 8.39). The end of the sutures are then brought through the tarsal plate and tied over it loosely to avoid kinking of the tarsal plate (Fig. 8.40).

Optimizing outcomes

Complications and Adverse Effects

The blepharoplasty complications can be divided into intraoperative, short-term postoperative and long-term postoperative risks. Intraoperative complications include anesthesia-related complications, the oculocardiac reflex, and excessive bleeding. Intraoperative excessive hemorrhage is commonly related to hypertension, coagulopathy and, possibly, the surgical technique. Hypertension may be controlled in the preoperative stages and perioperatively with sedation and hypertensive medications. In the absence of hypertension the excessive bleeding should be investigated by a coagulation profile, including a screening for von Willebrand’s disease. If the bleeding persists, 16-20 μg of desmopressin (DDAVP) can be infused over a period of 30-45 minutes while the patient’s blood pressure is being monitored for hypertension. The patient should be observed closely postoperatively for thrombophlebitis, oliguria, and the very unlikely possibility of coronary blockage. In patients with known coronary artery disease, use of desmopressin is not advisable.

Blindness is the most dreaded complication of blepharoplasty and the incidence in the literature ranges from 1 : 2000 to 1 : 5000 cases.24,41 The loss of vision is thought to be due to a retrobulbar hemorrhage causing increased intraorbital pressure. This hemorrhage is thought to cause compression of the ciliary arteries which results in ischemia of the optic nerve. Another theory is ischemia of the optic nerve due to constriction of the retrobulbar blood vessels in response to epinephrine in the local anesthetic. A patient’s complaint of significant pain, pressure, excess swelling or visual disturbances should be investigated vigorously in order to avoid this complication. Immediate consultation with an ophthalmologist is crucial if there is any evidence of loss of vision.

Diplopia as a result of injury of the extraocular muscles is the next most severe complication. This will result from transection or surgical injury to the inferior oblique, inferior rectus or superior oblique muscles. These muscles may be injured during fat resection and dissection of the inferior or superior eyelid respectively.42 Meticulous surgical technique and observation of tissue planes will help to prevent this complication.

Pre-existing keratoconjunctivitis sicca or dry eye is a relative contraindication to eyelid surgery. Any surgery that may cause lagophthalmos or exposure keratopathy in a patient with dry eye will result in corneal epithelial breakdown and possible corneal ulceration. Ophthalmic consultation should be obtained for any patient with a history or symptoms consistent with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Patients with exposure keratopathy may complain of tearing secondary to the tear reflex arc that is stimulated by corneal exposure. Frequent lubrication with ophthalmic ointment or artificial tears, or the use of an occlusive eyelid cover that retains the moisture, may alleviate some of the symptoms of a patient with exposure keratopathy.

Postoperative Care

Pitfalls

1. Anton S. Skin-muscle flap lower lid blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:305-308.

2. Beard C. Ptosis, ed 3. St. Louis: Mosby, 1981.

3. Bourguet J.V. Les herniew graisseuses de l’orbite. Notre traitement chirurgical. Bull Acad Med (Paris). 1924;92(ser3):1270-1272.

4. Bowman WP. Report of the chief operations performed at the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital for the quarter ending Sept. 1857. Ophth Hosp Rep and J Royal Lond Ophth Hosp 1857-1859, vol 1, 34.

5. Charpy A. Le coussinet adipeux du sourcil. Bible Anat. 1909;19:47.

6. Collin J.R. Blepharochalasis. A review of 30 cases. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;7:153-157.

7. Cstanares S. Blepharoplasty for herniated intraorbital fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1951;8:46-58.

8. DeMere M., Wood T., Austin W. Eye complications with blepharoplasty or other eyelid surgery. Plast Reconst Surg. 1974;53:634-637.

9. Doxanas M.T. Minimally invasive lower eyelid blepharoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1327-1332.

10. Farris R.I., Stuchell R.N., Mandel I.D. Basal and reflex human tear analysisI. Physical measurements: osmolarity, basal volumes, and reflex flow rate. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:852-857.

11. Fuchs E. Ueber Blepharochalasis (Erschlaffung der Lidhaut). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1896;9:109.

12. Furnas D.W. The orbicularis oculi muscle. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8:687-715.

13. Hamra S.T. Repositioning the orbicularis oculi muscle in the composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;90:14-22.

14. Hamra S.T. The role of orbital fat preservation in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;23:85-89.

15. Hester T.R., Codner M.A., McCord C.D. Subperiosteal malar cheek lift with lower lid blepharoplasty. In: McCord C.D., editor. Eyelid reconstruction. New York: Raven Press, 1995.

16. Horton C., Carraway J., Austin D. Treatment of a lacrimal bulge in blepharoplasty by repositioning the gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:701-702.

17. Jordan D.R., Anderson R.L., Thiese S.M. Avoiding inferior oblique injury during lower blepharoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1382-1383.

18. Kersten R.C. Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 7; Academy of Ophthalmology. 2007.

19. Kohn R. Textbook of ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1988.

20. Kolle F.S. Plastic and cosmetic surgery. New York: D Appleton & Co, 1911.

21. Lisman R., Rees T., Baker D., et al. Experience with tarsal suspension as a factor in lower lid blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:897-905.

22. Matarasso A. The oculocardiac reflex in blepharoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:243-250.

23. May J.Jr, Fearon J., Zingarelli P. Retro-orbicularis oculi fat (ROOF) resection in aesthetic blepharoplasty: a 6 year study in 63 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:682-689.

24. Meyer D.R., Linberg J.V., Wobig J.L., et al. Anatomy of the orbital septum and associated eyelid connective tissues. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;7:104-113.

25. Miller C.C. Cosmetic surgery. The correction of featural imperfections. Chicago: Oak Printing Co, 1907.

26. Miller C.C. The excision of bag-like folds of skin from the region about the eyes. Med Brief. 1906;34:648.

27. Naugle T.C. Lower blepharoplasty with emphasis on horizontal eyelid shortening. Facial Plast Surg. 1984;1:299.

28. Nerad J.A. The requisites in ophthalmology: oculoplastic surgery. St Louis: Mosby Inc, 2001.

29. Putterman A.M., Urist M.J. Müller muscle-conjunctival resection: technique for treatment of blepharoptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:619-623.

30. Putterman A.M., Urist M.J. Surgical anatomy of the orbital septum. Ann Ophthalmol. 1974;6:290-294.

31. Guyuron B., Davies B. Experience with the modified putterman procedure. Plast, Reconstr, Surg. 1988;82:775-780.

32. Rees T., Jelks G. Blepharoplasty and the dry eye syndrome: guidelines for surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:249-252.

33. Smith B., Petrelli R. Surgical repair of prolapsed lacrimal glands. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:113-114.

34. Spica M. Blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:121-137.

35. Tessier P. The conjunctival approach to the orbital floor and maxilla in congenital malformation and trauma. J Maxillofac Surg. 1973;1:3.

36. Tomlinson F., Hovey L. Transconjunctival lower lid blepharoplasty for removal of fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:314-318.

37. Trelles M.A., Kaplan I., Rigau J., et al. Periocular skin reshaping by CO2 laser coagulation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20:327-331.

38. Ullman Y., Levi Y., Ben-Izhak O., et al. The surgical anatomy of the fat in the upper eyelid medial compartment. Plast Reconst Surg. 1997;99:658-661.

39. Whitnall S.E. On a ligament acting as a check to the action of the levator paplebrae superioris muscle. J Anat Physiol. 1910;14:131.

40. Yousif N.J., Sonderman P., Dzwierznsky W. Anatomic considerations in transconjunctival blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1271-1276.

41. Zarem H., Resnick J. Expanded applications for transconjunctival lower lid blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:215-220.

42. Zide B., Jelks G. Surgical anatomy of the orbit. New York: Raven Press, 1985.