19 Perioral filling

Summary and Key Features

• The perioral region is particularly susceptible to the signs of aging

• Biodegradable fillers can improve the appearance of vertical lip rhytides, oral commissures, and the chin and jawline

• Permanent fillers should not be used in the lips

• Fillers are often combined with neuromodulation to control movement and increase longevity of the filling agent in the lower face and in the lips

• Conservative treatment with small doses is recommended

• Many complications can be avoided by careful injection techniques and suitable product selection

Anatomical considerations

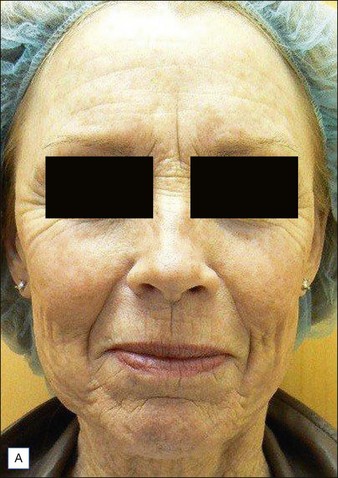

Age-related changes are a result of a combination of factors, including loss of subcutaneous volume, thinning of the dermis, changes in bony structures, skin laxity due to loss of collagen and elastin, and downward gravitational shift of the skin and underlying tissues. Over the years, the entire perioral region begins to droop. The lips may deflate and flatten, vertical rhytides appear above and below the vermilion lips, the mandible rotates (downward and backward for women; forward for men), and oral commissures turn down emphasizing the drooping mouth and prominence of the marionette lines. Soft tissue atrophy and bone reduction in the region between the chin and jowl result in a groove termed the pre-jowl sulcus. Redistribution of overlying skin and subcutaneous tissues results in the underprojection of the chin and malar eminences. Loss of definition occurs around the mandible, and the mentalis area develops a pebbled ‘peau d’orange’ appearance owing to repetitive muscular activity in conjunction with volume loss in the chin (Fig. 19.1).

Injection techniques

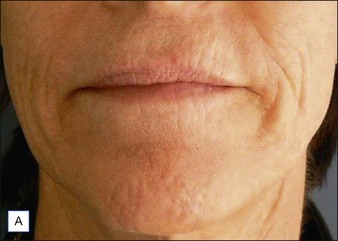

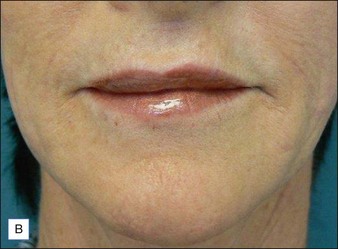

Like the choice of appropriate filling agent, injection techniques vary. Initial patient evaluation should include an overall assessment of the diffuse volume deficit, as well as the individual lines and depressions for a multifaceted treatment approach (Fig. 19.2). In some cases, rejuvenation of the lower face can be accomplished with filling agents alone using a conservative approach and follow-up visits to assess the need for additional treatment. Because of the dynamic nature of the perioral region, fillers often do not last as long as they do in less mobile locations. For this reason, restoration of volume in the lower face is often combined with movement control via botulinum toxin (BoNT). Indeed, combination therapy has been shown by numerous studies to work synergistically, providing optimal and longer lasting clinical benefits than with either modality alone. Some clinicians consider combination therapy the standard for rejuvenation in the lower face.

Vertical lip lines

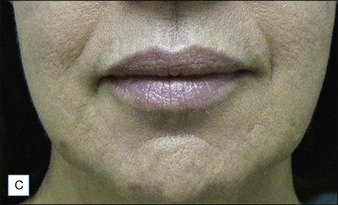

Because vertical lip rhytides, called ‘smoker’s’ or ‘lipstick’ lines, can range from faintly etched multiple lines to deep grooves, treatment techniques will vary. Injections can be placed along the length of the line, slightly perpendicular, or across the lip platform, and any combination of these approaches may be used. Treatment of the entire lip platform may benefit patients with multiple small lines. The platform is filled conservatively, beginning injections laterally above the white roll and using the push-ahead technique, which can decrease the number of injection sites required for correction. Multidirectional injections on the lip platform may be required for widespread correction of perioral rhytides (Fig. 19.3).

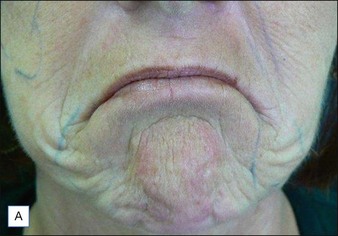

Oral commissures

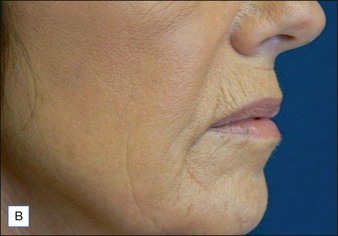

A combination of serial puncture and linear threading has been reported in the literature, with the former preferred for deep depressions and lateral lip festoons, and the latter for shallower grooves and less extensive downturns of the mouth. The 30-gauge, 1-inch (2.5 cm) needle is inserted in the mid-dermal level of the modiolus with the patient’s mouth slightly open, while the non-injecting hand holds the skin taut. Slow injection using the ‘push ahead’ technique allows the filler to precede the needle tip through the delicate tissues, reducing injection-related adverse events (Fig. 19.4). In some cases, injections may need to extend into the white roll of the upper lateral lip or higher to elevate the angle of the mouth. Injecting the lateral upper lip and lateral lower lip and extending the filling agent support inferiorly down the melomental fold to the mandibular margin can increase longevity of the result. Cross-hatching may be used in patients requiring extensive correction or to fill the triangular area of the commissures. The needle is inserted approximately 1 cm below the lip, and a linear threading technique is used to inject along the lip and into the marionette lines. As much as 1.5 mL of HA may be used on each side to provide adequate fullness, particularly in older patients. Mouth corners often cannot be adequately addressed without adding extra support to the pre-jowl and perimental areas (see below).

Augmentation of the jaw and chin

Augmentation of the chin can improve its shape and forward protrusion and sharpen the jawline. Typically 0.2–0.4 mL of filler material is injected subdermally into the regions superior and lateral to the mentum (Fig. 19.5). Filling the pre-jowl sulcus – indentations along the jaw directly below the corners of the mouth that interrupt the smooth line of the jaw – smoothes the mandibular border, while augmentation of the perimental hollows and labiomental crease gives additional support to the entire chin complex (Fig. 19.6). The key to correcting the pre-jowl sulcus is the recreation of the inferior border of the mandible, rather than simple volume replacement along the body of the mandible. To correct the pre-jowl sulcus, filler is placed in the deep dermis in the subdermal plane while taking care to avoid the facial artery and vein, which are pre-periosteal. Incremental, slow injection combined with gentle massage can create a smooth correction that blends well with the adjacent chin and jaw contours.

Conclusion

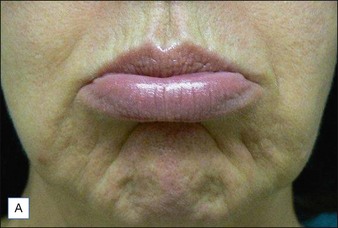

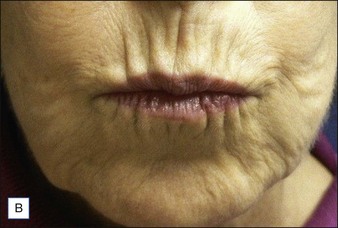

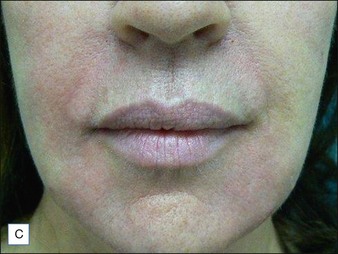

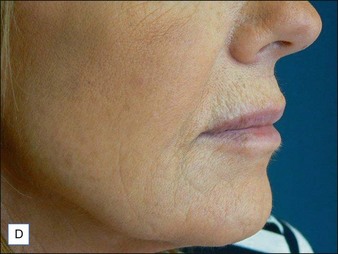

A 69-year-old woman of Northern European extraction had undergone a facelift 7 years previously. She is worried about her recurrent facial lines and the deflation of her cheeks and chin. She would like to see a smoother, softer, less fatigued and stressed expression, but does not wish to have another facelift or laser resurfacing. Her health is excellent and she is very keen to proceed with treatment that is non-invasive, effective, and safe. We discussed the use of neurotoxin injections to relax the ‘mouth frown’, perioral lines, and the platysmal bands. Also, the addition of a hyaluronic acid filler, which is reversible if necessary and safe to use, throughout the face will recontour the facial skin envelope. The combined use of neurotoxin and filler give a superior result, both initially and over time, since the neurotoxin stops degradation of the filler through repetitive motion, particularly in the perioral area. Before (Fig. 19.7A, B) and after (Fig. 19.7C, D) photographs demonstrate the rejuvenating effect of 96 units of onabotulinumtoxinA and 9 mL of Juvéderm® Voluma injected in the forehead, temples, glabella, nasal bridge, infraorbital hollows, cheeks, perioral region, lips and chin, and mandibular margin.

Agarwal A, Dejoseph L, Silver W. Anatomy of the jawline, neck, and perioral area with clinical correlations. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2005;21:3–10.

Atamoros FP. Botulinum toxin in the lower one third of the face. Clinical Dermatology. 2003;21:505–512.

Carruthers J, Klein AW, Carruthers A, et al. Safety and efficacy of Restylane for improvement of mouth corners. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:1–5.

Carruthers JDA, Glogau RG, Blitzer A, the Facial Aesthetics Consensus Group Faculty. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type A, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(suppl 5):S5–S30.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Monheit GD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of the safety and effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 4):2121–2134.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Monheit GD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation: satisfaction and patient-reported outcomes. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 4):2135–2145.

De Boulle K, Swinberghe S, Engman M, et al. Lip augmentation and contour correction with a ribose cross-linked collagen dermal filler. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2009;9(suppl 3):1–8.

Glogau RG, Kane MA. Effect of injection techniques on the rate of local adverse events in patients implanted with nonanimal hyaluronic acid gel dermal fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(suppl 1):S105–S109.

Gold MH. Use of hyaluronic acid fillers for the treatment of the aging face. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2007;2:369–376.

Klein AW. In search of the perfect lip: 2005. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:1599–1603.

Lemperle G, Rullan PP, Gauthier-Hazan N. Avoiding and treating dermal filler complications. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118:S92–S107.

Perkins NW, Smith SP, Jr., Williams EF, 3rd. Perioral rejuvenation: complementary techniques and procedures. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2007;15:423–432.

Petrus GM, Lewis D, Maas CS. Anatomic considerations for treatment with botulinum toxin. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2007;15:1–9.

Sclafani AP. Soft tissue fillers for management of the aging perioral complex. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2005;21:74–78.

Tan SR, Glogau RG. Filler esthetics. In: Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Procedures in cosmetic dermatology series: soft tissue augmentation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Weinkle S. Injection techniques for revolumization of the perioral region with hyaluronic acid. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2010;9:367–371.