Chapter 14 Perioperative monitoring in obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is a prevalent condition resulting from a decrease in upper airway size and patency during sleep. Apneas, hypopneas and episodes of airflow limitation occur during sleep resulting in physiological changes including reductions in oxygen saturation and arousals from sleep. Arousals lead to cessation of the respiratory event, only to be followed by repetitive airflow obstructions and arousals. The arousals cause sleep fragmentation, and secondary daytime symptoms including non-restorative sleep, excessive daytime somnolence, memory loss and other psychometric changes. Arousals also lead to a rise in sympathetic tone, with secondary changes in blood pressure, pulse and cardiac output. In addition to the nocturnal and daytime symptoms, obstructive sleep apnea may contribute to significant complications including hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

2 PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

2.1 SELECTION OF A SURGICAL FACILITY

The surgeon must select an operating room with personnel and equipment adequate for an elective and controlled management of the patient’s airway. Preoperative preparation is intended to improve a patient’s medical status and reduce the risk of complications. The literature is insufficient to offer guidance regarding which patients can be safely managed as an outpatient as opposed to an inpatient basis or the appropriate time for discharge from the surgical facility.1

The determination to perform surgery as an outpatient, in an outpatient surgery center with ambulance transfer to a hospital facility, admit for a short extended recovery room stay, admit to a 23-hour unit, regular hospital room or an intensive care unit should be made with consideration of associated co-morbidities, severity of apnea, sites of airway narrowing, type of anesthesia, length of time for anesthesia, need for postoperative narcotic agents, and type of surgery being performed. This determination should be made preoperatively.1 Confusing the matter is the use of the term ‘outpatient’ by some organizations to refer to all surgical stays less than 24 hours and by other organizations to label any stay after midnight as ‘inpatient.’ In a recent report of the American Society of Anesthesiologists,1 consultants were surveyed using a non-validated scoring system about opinions regarding outpatient surgery in patients with OSAS. This survey suggested that a patient with mild sleep apnea undergoing uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) or nasal surgery was not at increased risk, while a patient with moderate sleep apnea undergoing UPPP was at increased risk of complications.1

2.3 USE OF CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE (CPAP)

There is an alteration of sleep architecture and frequently sleep deprivation prior to and after surgery, including sleep deprivation due to anxiety about the surgery.2,3 Once surgery is done and these factors are gone, however, the patient is more likely to enter deeper levels of sleep and may be predisposed to more severe sleep apnea.4 It would therefore seem to be beneficial to improve sleep quality as much as possible before and after surgery. When possible, a patient should be asked to use CPAP for several weeks prior to and after surgery and to bring their machine into the hospital for perioperative use. While the majority of patients are undergoing surgery because they cannot tolerate CPAP, even moderate use of CPAP preoperatively may be beneficial.

2.4 USE OF NARCOTICS AND SEDATIVE AGENTS

Use of narcotics, sedative hypnotics and anxiolytic agents should be avoided prior to surgery in a patient with OSAS. These agents have been reported to lead to sudden death, even in the preoperative holding area.5 These drugs suppress respiration, blunt the arousal response and may lead to life-threatening hypoxemia. Benzodiazepine agonists affect upper airway muscle tone and worsen sleep apnea.6 Flurazepam has been shown to increase the Apnea Index7 and triazolam increased the arousal threshold to airway obstruction, apnea and hypopnea duration and oxygen desaturation.8 If a sleep apnea patient requires sedation or an anxiolytic, this necessitates require continuous pulse oximetry, and possibly supplemental oxygen.

2.5 REFLUX/ASPIRATION PRECAUTIONS

Obesity is common in patients with sleep disordered breath-ing, leading to an increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux9,10 which is caused by increased intra-abdominal fat, intra-abdominal pressure and higher incidence of hiatal hernia. Ninety percent of obese patients have greater than 25 ml of gastric fluid prior to surgery, a pH under 2.5 and will be at increased risk of aspiration during induction of anesthesia11 or upon extubation. In order to reduce these risks, obese patients should receive an H2 blocker, proton pump inhibitor or esophageal motility stimulant prior to surgery.12

2.6 MEDICAL/ANESTHESIA/CARDIOLOGY CLEARANCE

Patients with OSAS are at increased risk of hypertension due to an increased sympathetic drive.13,14 Undiagnosed hypertension is common in the sleep apnea patient. Blood pressure screening should be done at the time of initial evaluation or after initial diagnoses of OSAS. If blood pressure is elevated, these patients should be referred for treatment. Blood pressure should again be checked at a preoperative visit to be sure that hypertension is well controlled.

3 INTRAOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

3.1 PREPARATION FOR INTUBATION (VENTILATION)

Prior to surgery, an anti-reflux agent and anti-sialogogue should be administered to reduce the risk of aspiration and reduce saliva production.12 It is important to maintain continuous control of the airway by the anesthesiologist. In order to ventilate the patient, the anesthetized patient will require positive pressure breathing by mask, head and neck extension, jaw protrusion, and insertion of a properly sized oral airway or long nasal airway in order to keep the tongue from falling posteriorly. A two-person ventilation approach may be needed, one for jaw positioning and mask seal and the other for ventilation.15 A 3–5 minute period of ventilation is used to increase oxyhemoglobin saturation and reduce the rate of desaturation, prior to intubation.

A variety of methods are available to maintain ventilation in a difficult airway (Table 14.1). The simplest approach is to insert a long nasopharyngeal airway that extends inferior to the base of tongue. A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is another excellent way to stabilize the airway and allow ventilation.16,17 The LMA is inserted blindly, and keeps the base of tongue and epiglottis from collapsing posteriorly. Other options require additional equipment and expertise such as use of a rigid ventilating bronchoscope, an esophageal–tracheal combitube, or the placement of a 14 gauge angiocath into the cricothyroid membrane followed by transtracheal jet ventilation.

| Oral airway |

| Long nasopharyngeal airways |

| Laryngeal mask airway |

| Esophageal–tracheal combitube |

| Rigid ventilating bronchoscope |

| Intratracheal jet stylet |

| Transtracheal jet ventilation |

3.2 INTUBATION TECHNIQUES

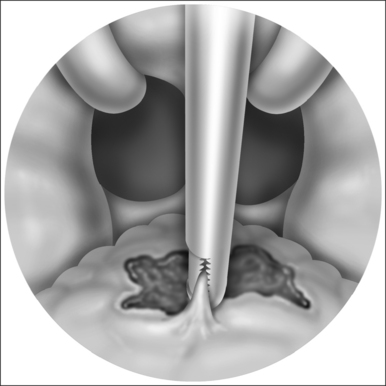

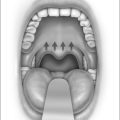

The sleep apnea patient can be a challenge to intubate due to the combination of skeletal deficiency, a long airway, excessive oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal soft tissue, and a relatively anterior larynx. If easily ventilated, then short-acting paralyzing agents such as succinylcholine may be used. Oral intubation may not be feasible if the larynx cannot be visualized. Alternative methods (Table 14.2) are available for difficult intubations. The safest approach is an awake oral or nasal intubation as the patient continues breathing. A more comfortable approach for the patient is a planned awake transnasal fiberoptic intubation performed with the patient in a sitting or semi-sitting position. Another simple option is the use of a light wand (lighted stilet) inserted into the endotracheal tube, with transcutaneous guidance into the trachea, in a darkened room. If the patient is ventilated through an LMA, then the easiest intubation approach is through the LMA. One of the newest approaches is the use of a video laryngoscope, which has a small video camera on the end, allowing the anesthesiologist to visualize the larynx on a screen. As a result, the endotracheal tube can be guided through the vocal cords, by visualizing the video screen.

| Awake intubation |

| Light wand |

| Fiberoptic intubation |

| Video laryngoscopes |

| Intubation through laryngeal mask airway (LMA) |

| Retrograde intubation |

| Blind nasal intubation |

A patient may also require a planned temporary or skinned lined tracheostomy. Planned tracheostomy should be considered in those with severe sleep apnea and failure of CPAP, those with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias or severe oxygen desaturation,18 or in those with a failed intubation at a prior surgery. Temporary tracheostomy should also be considered if significant postoperative edema is expected. An emergency tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy may be needed if a patient cannot be ventilated or intubated.

3.3 EXTUBATION

Extubation is another critical time due to potential airway obstruction. Full reversal of neuromuscular block should be verified prior to extubation. The patient should have purposeful movement, recovery of neuromuscular activity, sustainable head lift for at least 5 seconds, and an adequate voluntary tidal volume. Whenever possible, the patient should be in the semi-upright or lateral position. In addition, it is generally accepted that patients should be extubated awake.1,19 Most anesthesiologists prefer not to extubate ‘deep’ as the airway may obstruct. However, if extubated light or awake, the patient may cough or buck on the tube and cause bleeding into the airway. As a result, there are certainly medical and surgical contraindications to awake extubation. In children, postobstructive pulmonary edema may occur with deep extubation due to negative pressure breathing against a closed airway. In general, if the patient was easy to ventilate with induction, there should be no difficulty ventilating after extubation. The patient should only be extubated with appropriate personnel and equipment present so as to be able to replace the tube if necessary.

It is unclear whether adjunctive local anesthetic agents improve operative safety. Use of long-acting local anesthetics at the conclusion of surgery may reduce the need for narcotic analgesics but may worsen apnea due to blockage of airway mechanoreceptors that contribute to the arousal stimulus and apnea termination.20 Narcotic agents should be minimized during surgery, as their effect may persist postoperatively and lead to postoperative complications.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Several studies have shown that apnea severity is unchanged or worse one to two nights following UPPP.21,22 Following surgery, multiple approaches are required to reduce those factors which may exacerbate sleep apnea and to closely monitor patients in order to give early warning of potential serious or fatal airway complications such as airway obstruction, hypoxemia, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke and death.

4.1 PATIENT POSITIONING

Sleep apnea severity and hypoxemia tend to improve when adult OSAS patients are tested in the sleep laboratory in the lateral, prone, or sitting positions rather than supine. Elevation of the head of the bed after surgery reduces soft tissue edema and turbinate engorgement, and improves the nasal airway. Since there are no valves in the veins of the head and neck, lying flat increases venous pressure and increases tissue edema. While the literature is insufficient to provide guidance for the postoperative period, most physicians agree that after airway surgery, the head of the bed should be elevated and the supine position should be avoided.1

4.2 PATIENT ANALGESIA

Reconstructive surgery for sleep apnea is often painful, requiring narcotic agents for adequate pain control.23 All opiate agents including morphine, meperedine, hydromorphone and fentanyl cause dose-dependent reduction of respiratory drive, respiratory rate, and tidal volume and can lead to hypoventilation, hypoxemia and hypercarbia.24,25 The literature is insufficient to evaluate the effects of different analgesic techniques and there is no agreement about the safety of nurse-administered versus patient-controlled analgesia with systemic opioids.1

In general, narcotic agents should be titrated for pain severity and used only as needed. Stronger narcotic agents should be used only when weaker analgesic agents are not adequate. Mild to moderate pain should be treated with oral opioid agents such as codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone and propoxyphene, as these agents have only mild respiratory suppressing effects. Non-narcotic options include centrally acting agents such as tramadol hydrochloride and acetominophen, which is often used in combination with opioid agents. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, tromethamine) may also be helpful but should be used with caution due to the potential for increased bleeding. Newer COX-2 non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents (celocoxib) probably have minimal bleeding risk. Topical anesthetics such as benzocaine may also be helpful for pain control.

4.3 OXYGENATION

Maintaining adequate oxygenation is mandatory following surgery. Supplemental oxygen should be continued in order to maintain the oxygen saturation above 90%. Supplemental oxygen may be discontinued when the patient is able to maintain their baseline oxygen saturation while breathing room air. CPAP can be safely used after most upper airway surgeries to prevent desaturation during sleep26 and should be used as soon as feasible after surgery in patients who were using it prior to surgery. Following surgery, CPAP may also reduce the risk of gastroesophageal reflux.27 Patients should be instructed to bring their own PAP machine to the surgery facility for postoperative use during sleep at the preset pressure. The CPAP pressure may be changed if needed: higher due to tissue edema or muscle relaxation; lower due to enlargement of the airway. CPAP should be avoided after maxillary advancement due to the risk of subcutaneous emphysema. After nasal surgery, CPAP can be used with a full face mask instead of a nasal mask or nasal pillows.

4.4 REDUCING AIRWAY EDEMA

Despite surgical correction of the upper airway, edema caused by surgical trauma or difficult intubation may cause airway compromise, especially in those with severe apnea, multiple sites of airway compromise, and multiple airway surgeries. Tissue edema occurs even after laser and radiofrequency (RF) procedures.28,29 Systemic steroids can reduce edema in the upper airway.30 Dexametasone (10–15 mg/dose in adults) is the preferred corticosteroid agent due to the limited effect on sodium retention. I administer steroids prior to surgery and several doses postoperatively.

Soft tissue edema may be reduced by tissue cooling. Tissue precooling reduces edema in thermal wounds from lasers30 or cautery units. Application of external ice packs or sucking on ice chips may also reduce swelling. Topical or systemic antibiotic prophylaxis may also reduce edema by reducing bacterial contamination of the surgical wound. Perioperative use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic agent with anaerobic coverage is recommended with oral or nasal surgery and topical chlorhexidine oral rinse has been shown to reduce bacterial counts in the oral cavity.

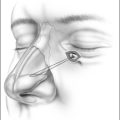

Nasal obstruction may cause or worsen sleep apnea31 while improving the nasal airway can improve sleep apnea.32 Nasal packing should be avoided in patients undergoing nasal surgery. Alternatives to packing include use of quilting septal sutures, septal splints, nasal tubes such as Doyle splints, or nasopharyngeal airways sewn into place. Use of a decongestant nasal spray (oxymetazoline) or a systemic decongestant postoperatively is also helpful following nasal surgery or nasal intubation.

4.5 POSTOPERATIVE MONITORING

The first 24 hours after surgery are probably the most critical time for complications, though deaths from complications have also occurred later, potentially from the accumulated effects of sleep deprivation, narcotic agents and REM rebound.33,34 Unfortunately, the literature is insufficient to offer guidance regarding the impact of telemetry monitoring, ICU or stepdown units versus routine hospital ward settings, or the appropriate duration of monitoring.1

Monitoring in the ICU has been recommended as a measure to decrease the risk of complications after OSAS surgery.35,36 Some older publications have recommended ICU monitoring to monitor oxygen saturation and cardiac arrhythmias21,22 while others have advocated ICU monitoring due to the high incidence of serious airway complications (13–25%) in patients undergoing UPPP.36,37 Newer publications have noted a much lower complication rate, likely due to more aggressive perioperative precautions to avoid tissue edema and excessive sedation.38,39 Other authors40 used the precautions listed in this chapter and reported an overall complication rate of 4% (1.4% airway issues, 1.4% bleeding) in 347 consecutive patients.

4.6 USE OF SEDATIVES POSTOPERATIVELY

Sedative hypnotics are frequently administered after surgery for complaints of insomnia. As discussed earlier in this chapter, sedative hypnotics and anxiolytics should be avoided due to the adverse effects on arousal thresholds, as well as apnea duration and severity. For patients with OSAS, short-acting non-benzodiazapine hypnotic agents may be safer than benzodiazepine hypnotics. Zaleplon (half-life 1 hour) and zolpidem tartrate (half-life 2.5 hours) have no significant effect on the Apnea/Hypopnea Index compared to placebo in mild to moderate sleep apnea patients.41 However, while zaleplon had no effect on the oxygen saturation, zolpidem reduced the lowest oxygen saturation compared to placebo as well as the total time with SaO2<90% and 80%, compared to the placebo group.

4.8 BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL

Patients with OSAS have a higher prevalence of hypertension and are at increased risk of postoperative hypertension due to an increased sympathetic tone.13,14 To maintain a postoperative systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg and diastolic below 90 mm Hg, over half of the patients undergoing upper airway surgery for OSAS will require an antihypertensive agent in the recovery room (unpublished observations, S. Mickelson MD). Blood pressure control during and after surgery is imperative in order to reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding and tissue edema. Blood pressure control is most important after osseous surgeries, since postoperative bleeding from bone is blood pressure dependent.

4.9 GENERIC PATIENT CARE PROTOCOLS

Physician and hospital patient care protocols for preoperative instructions and postoperative orders are often utilized for surgery.42 Institution protocols should be examined to be sure that routine recovery room, surgical ward, or extended recovery unit orders are appropriate for the sleep apnea patient (see Tables 14.3 and 14.4). Nursing checks should be more frequent than for the non-OSAS patient, in order to visually check the patient’s breathing status and be sure there is no labored breathing.

Table 14.4 Standard postop orders after sleep apnea surgery

|

12. Pt is to wear his/her own CPAP/BIPAP machine, whenever sleeping, beginning in recovery room. If patient underwent nasal surgery, use a CPAP full face mask.

|

4.10 CRITERIA FOR DISCHARGE

The patient should not be discharged home until swallowing is adequate to maintain hydration and adequate nutrition at home. The patient should not be discharged until there is adequate pain control with oral analgesics. The literature is insufficient to offer guidance about the appropriate time for discharge of these patients. Consultants to the ASA agreed that the room air oxygen saturation should return to its preoperative baseline, that patients should not be hypoxemic or develop airway obstruction when left undisturbed, and that these patients should be monitored for 7 hours after the last episode of airway obstruction or hypoxemia while breathing room air in a non-stimulating environment.1

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. A report by the ASA Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1081-1093.

2. Aurell J, Elmqvist D. Sleep in the surgical intensive care unit: continuous polygraphic recording of nine patients receiving postoperative care. BMJ Clin Res Ed. 1985;290:1029-1032.

3. Rosenberg J, Rosenberg-Adamsen S, Kehlet H. Post-operative sleep disturbances: causes, factors and effects on outcome. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1995;10(Suppl):28-30.

4. Cullen DJ. Obstructive sleep apnea and postoperative analgesia – a potentially dangerous combination. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13:83-85.

5. Fairbanks DNF. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty complications and avoidance strategies. Otolaryngol H&Neck Surg. 1990;102:239-245.

6. Bonara M, St John WM, Bledsoe TA. Differential elevation by protriptyline and depression by diazepam of upper airway motor activity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:41-45.

7. Guilleminault C, Silvestri R, Mondini S, Coburn S. Aging and sleep apnea: action of benzodiazipine, acetozolamide, alcohol and sleep deprivation in a healthy elderly group. J Gerontol. 1984;39:655-666.

8. Berry RB, Kouchi K, Bower J, Prosise G, Light RW. Triazolam in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:450-454.

9. DeMeester TR, Johnson LF, Joseph GJ, Toscano MS, Hall AW, Skinner DB. Patterns of gastroesophageal reflux in health and disease. Ann Surg. 1976;184:459-470.

10. Mercer CD, Wren SF, DaCosta LR, Beck IT. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure and gastroesophageal pressure gradients in excessively obese patients. J Med. 1987;18:135-146.

11. Vaughan RW, Bauer S, Wise L. Volume and pH of gastric juice in obese patients. Anesthesiology. 1975;43:686-689.

12. Warwick JP, Mason DG. Obstructive sleep apnoea in children. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:571-579.

13. Worsnop CJ, Pierce RJ, Naughton M. Systemic hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1993;16:S148-S149.

14. Bonsignore MR, Marrone O, Insalaco G, Bonsignore G. The cardiovascular effects of obstructive sleep apnoeas: analysis of pathogenic mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:786-805.

15. Benumof JL. Management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087-1110.

16. Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 1993;78:597–602.

17. Benumof JL. Laryngeal mask airway and the ASA difficult airway algorithm. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:686-699.

18. Mickelson SA. Upper airway bypass surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1996;31:1013-1023.

19. Meoli AL, Rosen CL, Kristo D, et al. Report of the AASM clinical practice review committee. Upper airway management of the adult patient with obstructive sleep apnea in the perioperative period – avoiding complications. Sleep. 2003;26:1060-1065.

20. Berry RB, Kouchi KG, Bower JL, et al. Effect of upper airway anesthesia on obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1857-1861.

21. Sanders MH, Johnson JT, Keller FA, Seger L. The acute effects of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on breathing during sleep in sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1988;11:75-89.

22. Johnson JT, Sanders MH. Breathing during sleep immediately after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:1236-1238.

23. Troell RJ, Powell NB, Riley TW, et al. Comparison of postoperative pain between laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, and radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:402-409.

24. Bailey PL, Egan TD, Stanley TH. Intravenous opioid anesthetics. In: Miller RD, editor. Anesthesia. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:273-376.

25. Mickelson SA. Perioperative and anesthesia management. In: Fairbanks DNF, Mickelson SA, Woodson BT, editors. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:223-232.

26. Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C, Murcia GN. Obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure, and surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;99:362-369.

27. Kerr P, Shoenut JP, Millar J, Buckle P, Kryger MH. Nasal CPAP reduces gastroesophageal reflux in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1992;101:1539-1544.

28. Terris DJ, Clerk AA, Norbash AM, Troell RJ. Characterization of postoperative edema following laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty using MRI and polysomnography: implications for the outpatient treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:124-128.

29. Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, Blumen MB, Guillemenault C. Radiofrequency volumetric reduction of the tongue. A porcine pilot study for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1997;111:1348-1355.

30. Sheppard LM, Werkhaven JA, Mickelson SA. The effect of steroids or tissue pre-cooling on edema and tissue thermal coagulation after CO2 laser impact. Lasers Surg Med. 1992;12:137-146.

31. Olsen KD. The nose and its impact on snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. In: Fairbanks DNF, editor. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. New York: Raven Press; 1987:199-226.

32. Dayall VS, Phillipson EA. Nasal surgery in the management of sleep apnea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94:550-554.

33. Rosenberg J, Rasmussen GI, Wojdemann KR, et al. Ventilatory pattern and associated episodic hypoxaemia in the late postoperative period in the general surgical ward. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:323-328.

34. Knill RL, Moote CA, Skinner MI, Rose EA. Anesthesia with abdominal surgery leads to intense REM sleep during the first postoperative week. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:52-61.

35. Macaluso RA, Reams C, Vrabec DP, Gibson WS, Matragrano A. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: post-operative management and evaluation of results. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:502-507.

36. Esclamado RM, Gleen MG, McCulloch TM, Cummings CW. Perioperative complications and risk factors in the surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1125-1129.

37. Haavisto L, Suonpaa J. Complications of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol. 1994;9:243-247.

38. Hathaway B, Johnson JT. Safety of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty as outpatient surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:542-544.

39. Kezirian EJ, Weaver EM, et al. Incidence of serious complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450-453.

40. Mickelson SA, Hakim I. Is post operative intensive care monitoring necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:352-356.

41. George CFP. Perspectives on the management of insomnia in patients with chronic respiratory disorders. Sleep. 2000;23(Suppl 1):S31-S35.

42. Mickelson SA. Avoidance of complications in sleep apnea patients. In: Terris DJ, Goode RL, editors. Surgical Management of Sleep Apnea and Snoring. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2005:453-464.