3 Perioperative Behavioral Stress in Children

Developmental Issues

Cognitive Development and Understanding of Illness

The perioperative period is stressful for many individuals undergoing surgery, and this is especially true for children. Children’s stress during the perioperative period results from multiple sources, one of which is a limited understanding of illness and the need for surgery. Early developmental theorists (e.g., Piaget,1,2 Werner3) suggested that a child’s understanding of illness changes qualitatively as cognitive maturation occurs. The most widely cited model for understanding a child’s perspective on illness posits that the child’s understanding of illness evolves from prelogical explanations, such as phenomenism (e.g., magical thinking), to concrete-logical explanations, such as contamination (e.g., eating bad food), to formal-logical explanations (e.g., physiologic causes), and differences in understanding occur according to the child’s differentiation between the self and others.4

Children’s understanding of the treatments for illnesses is thought to follow a similar developmental pattern. In terms of surgery, a child’s concepts are particularly underdeveloped. Young children have difficulty defining “an operation,” suggesting that it is the same as being sick, going for a doctor’s checkup, or taking a nap.5 Given these developmental considerations, it is not surprising that young children are more likely to have misconceptions about hospitalization and surgery than are older children and adults,6 and therefore are at unique and disparate risk for perioperative stress.

Attachment

Coping with separation is a lifelong challenge that is inevitable and necessary for a child’s normal, healthy development.7 Separation experiences, such as saying good-bye at school or sleeping overnight at a friend’s house, facilitate normal childhood psychological growth and personality organization by mobilizing opportunities for learning and adaptation. Other separation experiences, especially those occurring in the context of loss, illness, or other stressors, can precipitate states of confusion, anger, and anxiety. Brief separations, such as those associated with surgery, are most stressful for infants, toddlers, and preschool-aged children. Indeed, for school-aged children, responses to separation may reflect, in part, response patterns established early in the preschool years.7 For children with biologically based vulnerabilities, such as a sensitivity to novelty and changes in routines, even expected separations may impose a greater degree of stress than for less sensitive children.7 Similarly, for children with developmental delay, separation may be experienced with a degree of anxiety and developmental stress more like that experienced by a younger child.

Attachment affects a child’s response to separation and is shaped through early experiences with the primary caregiver. Through these interactions, an infant has the opportunity to develop a sense of trust and security in the reliability and predictability of his or her relationship and the world.8 The style of attachment exhibited by infants is evident in their responses to brief separations from the primary caregiver and is conceptualized as secure, insecure, or anxious.

Children who are more “securely attached” to their parents deal more adaptively with the stress of brief separation and with the novelty of the hospital experience. Such children are more willing to explore their world and respond positively to their caregivers’ return, using the caregivers as a secure, stable base from which to approach strangers and new situations.9,10 In contrast, children classified as “anxiously attached” to their parents tend to be distressed in unfamiliar situations, like the perioperative environment, even in the presence of their caregivers. When their parents return after brief separations, these infants exhibit anger and distress and avoid physical contact. Another form of “insecure attachment” is avoidance. Avoidant children do not explore their surroundings as much as securely attached infants, rarely show distress at separation, and tend to ignore their parents on reuniting. Conversely, “insecurely attached” infants are more easily distressed by even brief separations and spend more time trying to stay close to their parents. They are less likely to explore and adapt positively to new situations.

Temperament

Responses of young children to the stress of the perioperative period also reflect the child’s temperament. Temperament refers to stable emotional and behavioral responses (e.g., emotionality, activity, attention, reactivity, sociability, etc.) that appear in infancy and are thought to be primarily genetic in nature.11 Three main dimensions have been proposed to classify infant temperament: emotionality, activity, and sociability.12 Emotionality refers to the ease with which an infant becomes aroused or anxious, especially in situations that might lead to fear, such as perioperative settings. Activity refers to the infant’s customary level of energy and intensity of behavior. Sociability reflects the infant’s tendency to approach or avoid others. These behavioral dimensions of temperament are also reflected in physiologic responses related to anxiety.13,14 In long-term studies, infants who are inhibited in the face of novelty continue to be so through early school age.15 Thus, temperament as a behavioral descriptor appears to characterize an enduring cluster of traits reflecting reactivity and anxiety regulation in the face of novelty.

Preoperative Anxiety

Anxiety in children undergoing anesthesia and surgery is characterized by feelings of tension, apprehension, and nervousness.16 This response is attributed to separating from parents, loss of control, uncertainty about anesthesia, and uncertainty about the surgery and its outcome.16 It is estimated that 40% to 60% of children develop significant fear and anxiety before their surgery.17 Furthermore, separation from parents and induction of anesthesia have been found to be the most stressful times during the surgical and anesthesia experience. Some children verbalize their fears explicitly, whereas others express their anxiety only by behavioral changes. Children may appear scared or agitated, breathe deeply, tremble, stop talking or playing, and start to cry. Some may wet or soil themselves, display increased motor tone, and actively attempt to escape from medical personnel.18 These behaviors may give children some sense of control in the situation and thereby diminish the damaging effects of a sense of helplessness.16,18 In addition to the behavioral manifestations detailed here, several studies have documented that anxiety before surgery is associated with neuroendocrine changes, such as increased serum cortisol, epinephrine, growth hormone, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as increased natural killer cell activity.19,20 Significant correlations between heart rate, blood pressure, and behavioral ratings of anxiety have also been reported.21,22

Risk Factors

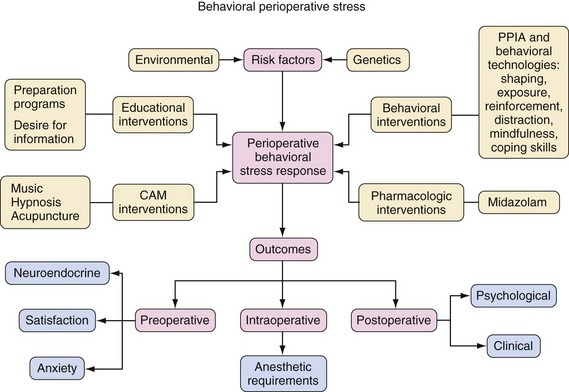

Preoperative anxiety is a clinically important phenomenon that should be treated as any other clinical phenomenon or disease. In epidemiologic terms, all diseases are characterized operationally by risk factors, interventions, and outcomes; preoperative anxiety is no exception. We review the phenomenon of preoperative anxiety using the classic epidemiologic model of a disease (Fig. 3-1).

Age and developmental maturity

Age and developmental maturity

Previous experience with medical procedures and illness

Previous experience with medical procedures and illness

Individual capacity for affect regulation and trait (baseline) anxiety

Individual capacity for affect regulation and trait (baseline) anxiety

Previous studies that examined the behavioral responses to induction of anesthesia in children did so in terms of these four domains.23–27 Children between the ages of 1 and 5 years are at greatest risk for developing extreme anxiety and distress. This is not surprising because separation anxiety often does not peak until 1 year of age and children older than the age of 5 years can more easily cope with new and unpredictable situations. A history of previous stressful medical encounters, such as with previous hospitalization, affects how a child reacts to new medical encounters; these are important risk factors for preoperative anxiety. Children who are shy and inhibited, as identified by temperament tests, and those who lack good social adaptive abilities, are also at increased risk for developing anxiety and distress before surgery.27

Parental characteristics also have a strong influence on a child’s behavior during the perioperative experience. Children of parents who are more anxious, children of parents who use avoidance coping mechanisms, and children of separated or divorced parents all appear to be at high risk for developing preoperative anxiety.28 Because children of anxious parents are more likely to experience high levels of preoperative anxiety, it is important to identify the predictors of increased parental preoperative anxiety. Parent gender (mothers are more anxious than fathers29), the child’s age (under 1 year), children with repeated hospital admissions, and the child’s temperament are all predictors of increased parental preoperative anxiety.28,30,31,32 Identification of children and parents who are at the greatest risk for preoperative anxiety and distress allows for appropriate intervention for this “at risk” population.

Behavioral Interventions

Pharmacologic (e.g., administration of premedications) and behavioral (e.g., psychological preparation programs) interventions are used to treat preoperative anxiety and distress in children and their parents.17,33

Preoperative Preparation Programs

Psychological preparation for children undergoing anesthesia and surgery has been widely advocated. These preparation programs may provide narrative information, an orientation tour of the operative facility, role rehearsal using dolls, modeling using videotapes or a puppet show, child life preparation, or coping education and relaxation skills.34,35,36

Although there is general agreement in the medical community about the benefit of preparation programs, recommendations regarding the content of behavioral preoperative preparation differ widely. Early programs were information oriented and often incorporated modeling techniques using videos or a puppet show.37,38 These techniques were augmented in the late 1980s with child life preparation and coping skills education.35 Child life specialists are trained individuals who facilitate development of coping skills and the adjustment of children and parents to the perioperative environment by providing play experiences, presenting information about events and procedures, and establishing supportive relationships with children and parents.36 Currently, the development of coping skills is considered the most effective preoperative intervention, followed by modeling, play therapy, operating room (OR) tour, and printed material.39 Interestingly, coping skills preparation with child life specialists was associated with less anxiety on the day of surgery when compared to lesser rated techniques; however, no differences were found immediately or up to 2 weeks after surgery.40 Thus, from a cost-effectiveness point of view, one must decide whether the additional cost associated with child life specialists is justified by reduction of anxiety only during the preoperative period.

It is important that preparation programs are tailored to the individual, age-appropriate needs of each child. Several variables have been identified as influencing the response of children to preparation programs.28 For example, children who are 6 years of age or older benefit most if they participate in a preparation program more than 5 days before the scheduled surgery and benefit least if the program is given only 1 day before surgery. In fact, older children prepared a week in advance showed an increase in anxiety level during and immediately after the preparation program, but demonstrated a gradual decrease in anxiety during the 5 days before the time of surgery.41 To avoid increasing excessive anticipatory anxiety, older children should be given enough time to process the new information and to rehearse newly acquired coping skills. It is also important to realize that there may be a negative effect of a preparation program on children younger than 3 years of age. This may be a result of their inability to distinguish fantasy from reality.1 A reality-based preparation program may do little to calm young children and may even exacerbate anxiety or sensitize the young child to the surgery. From age 3 to 6 years, children demonstrate an increasing ability to distinguish fantasy from reality and by the age of 6 this distinction is usually accomplished.1 Therefore, to provide the most benefit, both the age of the child and timing must be factored into delivery of the program.

In addition to age and timing, previous experience in a hospital setting also influences the effectiveness of a preparation program. A child who was previously hospitalized is more likely to develop an exaggerated emotional response to a behavioral preoperative preparation program and the perioperative experience.28,41–43 Information about what will occur, as demonstrated by sensory expectation and doll play, does not provide new information for these children. Furthermore, if the child has had a previous negative medical experience, the routine preparation may increase anxiety by triggering negative memories. In this case, alternative behavioral interventions, such as extensive individualized coping-skills training combined with desensitization and actual practice, may be better suited and indicated.42

Because increased parental preoperative anxiety has been shown to result in increased preoperative anxiety in their children, preparation programs for surgery should also be directed at parents.23 Although various interventions are routinely used to reduce a child’s anxiety, there is a paucity of information regarding interventions directed toward reducing parental anxiety.44 One study demonstrated that parental preoperative anxiety decreased after viewing an educational videotape.45 Most studies to date suggest that preoperative preparation programs for children reduce preoperative anxiety and enhance coping.35,41,46

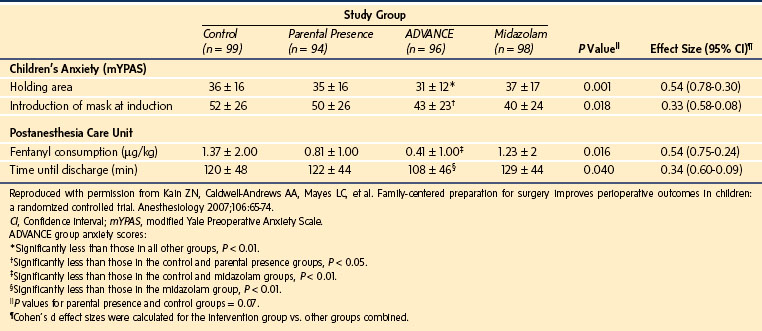

Children whose parents have been taught to be active in distracting their child during stressful medical events may evidence lower anxiety compared to parents who receive no intervention.47 Indeed, this was the case in a randomized controlled trial evaluating a family-centered behavioral preparation program (ADVANCE) (Table 3-1). Parents and children who received ADVANCE were less anxious before and during induction of anesthesia than parents and children who did not receive this program. In fact, ADVANCE was as successful as midazolam in managing children’s compliance with and anxiety at induction of anesthesia (Table 3-2).48 It is important to note that ADVANCE also decreased the time spent in the postanesthesia care unit and decreased the analgesic requirements during the postoperative period. A major disadvantage of ADVANCE, however, is its high cost and personnel requirements. Accordingly, efforts to dismantle this multimodal intervention indicate that behavioral shaping through exposing children to the anesthesia mask before surgery and distraction on the day of surgery proved to be the most effective components of the program.49

TABLE 3-1 The ADVANCE Preoperative Preparation Program

Distraction on the day of surgery

Video modeling and education before surgery

Adding parents to the child’s surgical experience and promoting family-centered care

No excessive reassurance—a suggestion made to parents for communication with children about surgery

Coaching of parents by researchers to help them succeed

Exposure/shaping of the child via induction mask practice (the mask placed over the child’s nose and mouth to deliver anesthetic drugs)

Reproduced with permission from Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2007;106:65-74.

Parental Presence during Induction of Anesthesia

It is well established that most parents and children prefer to remain together during procedures such as immunization, bone marrow aspiration, and dental treatment.50,51 Several survey studies have also indicated that most parents prefer to be present during induction of anesthesia regardless of the child’s age or previous surgical experience.52,53 This is even the case for those parents who have had previous experience with pharmacologic interventions. Indeed, parents of children undergoing repeated surgery were likely to request parental presence regardless of their experience with prior parental presence or premedication with midazolam.54 That is, even if children were calm after midazolam during their first surgery, parents still preferred to be present during induction of anesthesia during subsequent surgeries.

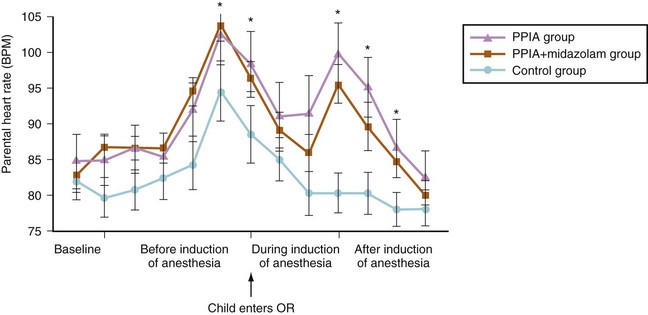

It is important to note, however, that parental presence during induction of anesthesia (PPIA) does not necessarily equate with appropriate choice of interventions. For example, mothers who were most highly motivated to be present at induction of anesthesia also reported high levels of anxiety and their children were more distressed at induction.55 Indeed, more than 90% of parents report some degree of anxiety during the anesthesia induction process.56 The most upsetting factors include seeing their child become flaccid during induction and separation from their child.56 This observation was confirmed by a study that examined heart rate, blood pressure, and skin conductance levels in mothers as they observed their child’s induction of anesthesia.57 Mothers who were present during induction of anesthesia showed a moderate increase in heart rate and blood pressure (Fig. 3-2). However, no cardiac arrhythmias or ischemic episodes were noted. Another study examined whether parental auricular acupuncture would reduce parental preoperative anxiety and thus allow children to benefit from parental presence during induction of anesthesia.58 A multivariate model demonstrated that children whose mothers had received the acupuncture intervention were significantly less anxious on entrance to the OR and during placement of the anesthesia mask on their child’s face.

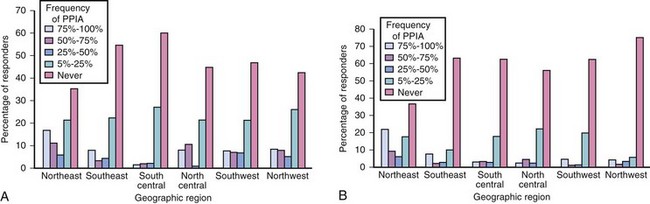

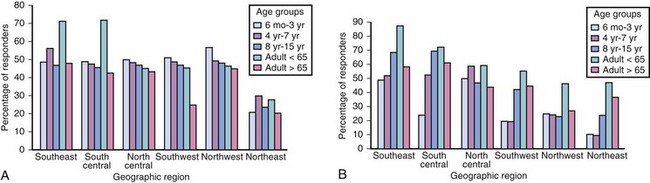

Potential benefits from PPIA include minimizing the need for premedication and avoiding the screaming and struggling of the child that may result on separation from the parents. Whether PPIA decreases child anxiety during induction and affects the long-term behavior effects of surgery and anesthesia remain controversial. Common objections to PPIA include concern about disruption of the OR routine, compromising operative sterility, crowded ORs, and a possible adverse reaction of the parent. For some children, their behavioral response to stress may be more negative when a parent is present than when the parent is absent.59 In several reports, PPIA resulted in disruptive behavior, parents refusing to leave the room when requested, and even removal of a child from the OR by a grandmother during the second stage of anesthesia.60,61 However, one report has described a 4-year experience with 3086 children in a freestanding ambulatory surgery center in which no parent needed to be escorted from the OR because of undue anxiety and only two parents developed syncope, with prompt recovery.62 Despite objections, the prevalence of PPIA is becoming more common in the United States. In fact, there has been an increase in the overall prevalence in PPIA from 1995 to 2002, and geographic differences in PPIA use decreased during the 7-year period (Fig. 3-3).63,64

The experimental evidence to date does not clearly support the routine use of PPIA.65–67 Although early studies suggested reduced anxiety and increased cooperation if parents were present during induction,68,69 more recent investigations indicate that routine PPIA may not always be beneficial.65–67 Characteristics of the parent and child have an impact on the effectiveness of parental presence. For example, older children (over 4 years), children with a “calm” and less active baseline temperament, parents with less situational anxiety, and parents with lower external locus of control benefit most from PPIA.30,65 The match between parent and child anxiety level also appears to be important. Calm children with anxious parents do more poorly during induction when compared with calm children with calm parents or anxious children with either calm or anxious parents.30 When interpreting the results of these studies, however, several factors should be considered. First, the design of a randomized controlled study, while considered a gold standard in research, may not reflect the practice of all anesthesiologists. That is, although a randomized controlled study is applicable to centers that offer PPIA for all parents, it may not be applicable to centers in which each request for PPIA is considered individually based on personality characteristics of each child and parent. Such centers may have different results with PPIA than were demonstrated in experimental studies. Second, allowing PPIA without adequate preparation of the parent may be counterproductive. Some parent behaviors, such as criticism, excessive reassurance, and commands, are associated with greater distress.70

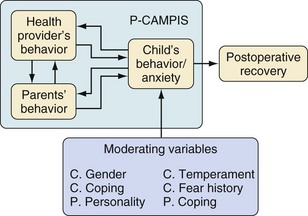

Given these drawbacks, interest in this area has begun to shift toward an emphasis on what parents actually do during induction of anesthesia. The development of a new tool for assessing child and adult behavior in the perioperative setting (Perioperative Child-Adult Medical Procedure Interaction Scale [P-CAMPIS]) has been developed to facilitate such research (Fig. 3-4).71 Preliminary validation of this measure indicates that parental behavior affects the child’s anxiety during induction much as it affects a child’s distress during immunizations.

The Preoperative Interview

Although not obvious, the preoperative interview is a behavioral intervention that is routinely administered to all children undergoing anesthesia and surgery.72 It is clear that anesthesiologists have an ethical and legal responsibility to disclose to children and parents detailed anesthetic risk information when obtaining informed consent, but how far this disclosure must extend remains controversial. A common reason given for not providing detailed anesthetic risk information is that it may increase the child’s or parents’ anxiety. Comparative studies investigating anxiety levels in adult patients given a limited amount of information, versus more detailed information concerning procedural and anesthetic risks, report conflicting results. Although early studies provided mixed data regarding whether detailed information delivered preoperatively increased anxiety,73–75 several studies in the United States and Australia have demonstrated that patients and parents who received detailed information, including numerical estimates of anesthesia-related complications, were no more anxious than those given minimal information regarding risks.76–78 Furthermore, parents have expressed their desire to have as much perioperative information about their child’s surgery as possible,77 and even children have expressed a desire for detailed perioperative information, including information about pain, anesthesia, and potential complications.79 Thus, the presentation of very detailed anesthetic information of what might go wrong should not increase parental or patient anxiety and has the advantage of allowing for fully informed choices. It should be emphasized, however, that anesthesiologists should note the particular coping style of the parents. Parents use different strategies to cope with or handle difficult, unclear, or unpleasant life experiences, such as a child undergoing surgery. Whereas some parents try to avoid information about unpleasant or unclear situations (“avoidance behavior”), others may seek any available information (“monitoring behavior”).80 Although a “monitoring” parent will benefit from a large amount of perioperative information, an “avoiding” parent may react to the information with increased anxiety and distress. Thus, the amount of information provided should be tailored to the needs of the individual parent.

Health Care Provider Interventions

In addition to behavioral interventions targeting children and their parents, a promising new line of research supports the use of behavioral interventions targeting health care providers—both anesthesiologists and nurses. Specifically, an empirically derived intervention titled Provider-Tailored Intervention for Perioperative Stress (P-TIPS) was shown to be successful in changing anesthesiologist and nurse behaviors in the perioperative setting and represents a new clinical avenue for decreasing perioperative anxiety in children.81 The development of P-TIPS was based on research documenting that adult behaviors (parents and health care providers) affect children’s distress during invasive medical procedures, including surgery. Specifically, the use of distraction, nonprocedural talk, and humor are conceptualized as “coping promoting” behaviors and have been shown to decrease children’s distress.82–88 Conversely, adults’ use of reassurance, apology, empathy, criticism, or allowing the child too much control over the medical procedure are conceptualized as “distress promoting” behaviors and lead to increased distress in children.82,87–90 With P-TIPS, a new behavior that affected child distress also emerged: medical reinterpretation (i.e., reconceptualizing medical experiences and equipment as nonthreatening) and was found to increase a child’s coping when used with medical experiences that were in the child’s immediate environment, but increase distress when used in reference to objects outside of the immediate environment.87

Preliminary investigation revealed that P-TIPS was successful at both increasing desired behaviors (coping promoting) and decreasing undesired (distress promoting) behaviors among health care providers.81 Both resident and attending anesthesiologists were included in this study and evidenced behavior change, as did OR nurses, who were charged with not only changing their own behaviors, but with changing parent behaviors in the perioperative setting as well. In fact, nurses demonstrated appropriate behavior change and, in turn, parents demonstrated increases in desired and decreases in undesired behaviors. One important benefit to the type of approach offered by P-TIPS is that it is not necessary to conduct individual training with parents of children undergoing surgery, rather health care providers who interact with multiple children and parents are targeted, which reduces both logistical and financial constraints of behavioral interventions.

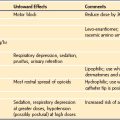

Pharmacologic Interventions

The primary goals of administering a premedication to children are to facilitate an anxiety-free separation from their parents and a smooth, stress-free induction of anesthesia. Other effects that may be achieved by pharmacologic preparation of the child include amnesia, anxiolysis, prevention of physiologic stress (e.g., avoiding tachycardia in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease), and analgesia (see Chapter 4).

The pattern of use of sedative premedications in the United States has changed over the past decade. Premedication use varied widely among age groups and geographic locations in 1996.63 Premedicant sedative drugs were least often prescribed for children younger than 3 years of age and most often prescribed for adults younger than 65 years of age (25% vs. 75%). When analyzed by geographic location, sedative premedications were used least often in the southwest and northeast regions and most often in the southeast region. A follow-up study revealed several interesting changes (Fig. 3-5).64 Most notably, the overall number of children undergoing surgery with premedication increased from 30% to 50%. There was also significantly less geographic variability in premedication use in 2002 than there was in 1996. In both years, the most commonly used sedative premedicant in the preoperative holding area was midazolam, followed by ketamine, transmucosal fentanyl, and meperidine. When data from several survey studies were reviewed, it was noted that anesthesiologists from the United States who allowed PPIA least used sedative premedication most frequently.63,91 Thus, most anesthesiologists in the United States use either parental presence or sedative premedication to treat preoperative anxiety in children.

Pharmacologic Interventions Versus Behavioral Interventions

When pharmacologic interventions are directly compared with behavioral interventions, children receiving a sedative are less anxious and more compliant than those who are accompanied to the OR by a parent.67 Interestingly, parental anxiety is also decreased when the child receives a premedication. Examining both sedative premedication and PPIA revealed that a combination of PPIA and sedative premedication was more effective than medication alone for reducing parent anxiety and improving parent satisfaction.92 However, PPIA offered no additional anxiolysis for children who received a sedative preoperatively. Nonetheless, parents who accompanied their sedated children into the operating rooms were themselves significantly less anxious and more satisfied both with the separation process and with the overall anesthetic, nursing, and surgical care provided. It is important to note that these parents had no preparation for their presence at anesthesia induction. Premedication combined with an advanced behavioral preparation resulted in similar outcomes on child and parent anxiety at induction and child compliance with induction.48 Furthermore, children who received behavioral preparation evidenced significantly less emergence delirium and required less analgesia in the recovery room compared with children who received only premedication.

Postoperative Outcomes

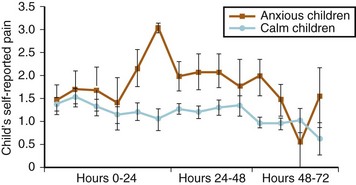

Four decades ago, it was proposed that moderate levels of preoperative anxiety in adult patients were associated with good postoperative behavioral recovery, whereas low and high levels of preoperative anxiety were associated with poor behavioral recovery.93 Although this theory is intriguing, these studies were based on descriptive data from nonrandom, limited samples and retrospective reports of questionable validity. Subsequent studies have reported a linear rather than a curvilinear relationship between anxiety level and postoperative behavioral recovery.94,95,96,97 In addition, increased preoperative anxiety in adult patients correlates with increased postoperative pain, increased postoperative analgesic requirements, prolonged recovery and hospital stay, and behavioral changes after surgery.23,98–101 Anxious children have been shown to experience significantly more pain both during the hospital stay and over the first 3 days at home102 (Fig. 3-6). During home recovery, anxious children also consumed significantly more codeine and acetaminophen compared with nonanxious children. Anxious children also had a greater incidence of emergence delirium (9.7% vs. 1.5%), postoperative anxiety, and sleep problems compared with nonanxious children. The investigators concluded that preoperative anxiety in young children undergoing surgery is associated with a more painful postoperative recovery and a greater incidence of disrupted sleep and other problems.102 Moreover, a recent study suggests that perioperative anxiety—not just preoperative anxiety—is associated with poorer surgical outcomes.103 That is, children have traditionally been conceptualized as anxious or nonanxious via assessment of anxiety in children before surgery, such as in the presurgical holding area or at the point of induction in the OR. By contrast, this study examined anxiety in children throughout the perioperative continuum (pre- and postoperatively) and replicated findings of associations between perioperative anxiety and both postoperative pain and new-onset behavioral changes.103

FIGURE 3-6 Children’s self-reported postoperative pain as a function of preoperative anxiety.

(From Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caldwell-Andrews AA, et al. Preoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics 2006;118:651-8.)

The assumption that minimal preoperative anxiety predicts good postoperative outcomes underlies many interventions in which the aim is to reduce preoperative anxiety. To date, preoperative preparation studies in adult patients have used diverse postoperative outcome measures, including intensity of pain, analgesic requirements, postsurgical complications, length of hospital stay, patient satisfaction, blood cortisol levels, changes in blood pressure and heart rate, and behavioral indices of recovery.96,104–111 Reviews of this research, while critical of the methodology, concluded that psychologically prepared adult patients may have improved postoperative recovery.99,104,112,113 As noted previously, children who received the ADVANCE preoperative program were less anxious preoperatively and experienced a reduced incidence of emergence delirium, had a briefer stay in the recovery area, reported less postoperative pain, and required fewer analgesics as compared with a control group.48

Emergence Delirium

The first maladaptive behavioral change in children that may be evident after surgery is emergence delirium. This phenomenon is characterized by nonpurposeful restlessness and agitation, thrashing, crying or moaning, and disorientation. Published studies have reported up to 18% of all children undergoing surgery and anesthesia develop emergence delirium.114 Factors such as young age, previous surgery, type of procedure, and type of anesthetic all affect the incidence of emergence delirium.114,115 Preoperative anxiety has also been shown to be related to emergence delirium.115,116 Furthermore, preoperative anxiety, emergence delirium, and postoperative maladaptive behavior changes have been shown to be closely related phenomena. One study found that the odds of children experiencing marked symptoms of emergence delirium increased in proportion with their preoperative anxiety scores, and that the odds of the onset of new maladaptive behavioral changes also increased with the presence of emergence delirium.102 This finding is highly significant to practicing clinicians, who can now predict the development of adverse postoperative phenomena, such as emergence delirium and postoperative behavioral changes, based on levels of preoperative anxiety.

Sleep Changes

Changes in sleep patterns in the postoperative period have been well documented in adults and children. One study reported that 47% of children experienced sleep disturbances after anesthesia117 and approximately 14% of children showed significant decreases in percentage of time spent asleep (in both REM and non-REM sleep) after surgery. The most common predictor of sleep difficulties after surgery has been postoperative pain,118 but psychological variables have also been shown to be important. Specifically, parental personality measures of anxiety and child measures of externalizing behavior have both been found to predict sleep efficiency in children after surgery.

Other Behavioral Changes

In addition to sleep, changes in daytime behavior in children after surgery and anesthesia have also been documented. A number of studies have indicated that up to 60% of children undergoing outpatient surgery may develop negative postoperative behavioral changes within 2 weeks after surgery.119–121 These negative postoperative behaviors include sleep and eating disturbances, separation anxiety, apathy, withdrawal, and new-onset enuresis.23,103,121 In fact, some children may develop long-lasting psychological effects that could have an impact on their responses to subsequent medical care. Interference with normal development has also been described.122 A significant number of children demonstrate new negative behaviors postoperatively, such as new onset of general anxiety, nighttime crying, enuresis, separation anxiety, temper tantrums, and sleep or eating disturbances. These behaviors may occur in up to 44% of children 2 weeks after surgery; about 20% of these children continue to demonstrate negative behaviors up to 6 months postoperatively.23 The postoperative negative behavioral changes are likely the result of an interaction between the distress the child experiences during the perioperative period and the individual personality characteristics of the child. Previously, variables such as the age and temperament of the child and the state and trait anxiety of the parent have been identified as predictors for the occurrence of negative postoperative behavioral changes.23 There is a paucity of data, however, regarding a possible association between the distress the child experiences during induction of anesthesia and the occurrence of these negative postoperative behavioral changes. One investigation concluded that extreme anxiety, such as that which occurs with a “stormy induction” of anesthesia, was associated with an increased incidence of postoperative negative behavioral changes.123 The investigators recommend that anesthesiologists advise parents of children who are anxious during induction of anesthesia of the increased likelihood that their children will develop postoperative negative behavioral changes, such as nightmares, separation anxiety, and aggression toward authority.123

Because the anxiety level of the child and mother in the preoperative holding area predicts the occurrence of negative postoperative behavioral problems,23 it can be hypothesized that if sedative premedications reduce anxiety of the child and the parents in the preoperative holding area, they may also have an effect on negative postoperative behavioral outcomes.70 One investigation of premedicated children found a significantly reduced incidence of negative behavioral changes during week 1 after surgery.124 This study suggests that reducing anxiety in the holding area has a beneficial effect on the behavior of the child preoperatively, as well as in the immediate postoperative period.124

Intraoperative Clinical Outcomes

It is commonly believed that increased anxiety before surgery is associated with increased intraoperative anesthetic requirements.95,125 This belief, however, is based on early studies of questionable scientific validity,126,127 many of which did not use validated scales to measure anxiety or control for potential confounding variables, such as sedative premedication and the surgical procedure.22 One investigation indicated that an increased baseline (i.e., trait) anxiety is associated with increased intraoperative anesthetic requirements in adults. The investigators in that study controlled for the surgical procedure, used bispectral electroencephalographic analysis (bispectral index) monitoring to ensure the same anesthetic depth in all patients, and used a total intravenous anesthetic technique to ease the calculation of the anesthetics used.128 As such, it does seem clear that an increased baseline, or trait, anxiety is associated with increased intraoperative anesthetic requirements.

Although several review articles suggest that increased anxiety before surgery and anesthesia is associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting,129 experimental data suggest that a child’s anxiety in the preoperative holding area is not predictive of postoperative nausea and vomiting either in the postanesthesia care unit or at home.130

Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC. Parental intervention choices for children undergoing repeated surgeries. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:970–975.

Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:65–74.

Kain ZN, Hofstadter MB, Mayes LC, et al. Midazolam: Effects on amnesia and anxiety in children. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:676–684.

Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caldwell-Andrews AA, et al. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;118:651–658.

Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Wang SM, et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia vs. sedative premedication: which intervention is more effective? Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1147–1156.

1 Piaget J. The language and thought of the child. New York: Meridian Books; 1955.

2 Piaget J. The child’s conception of the world. Princeton, N.J.: Littlefield, Adams & Company; 1960.

3 Werner H. Comparative psychology of mental development. Oxford, England: Follett; 1948.

4 Bibace R, Walsh ME. Development of children’s concepts of illness. Pediatrics. 1980;66:912–917.

5 Redpath CC, Rogers CS. Healthy young children’s concepts of hospitals, medical personnel, operations, and illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 1984;9:29–40.

6 Harbeck-Weber C, Fisher JL, Dittner CA. Promoting coping and enhancing adaptation to illness. In: Roberts MC, ed. Handbook of pediatric psychology. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2003:99–118.

7 Provence S, Mayes L, Lewis M. Separation and deprivation. In: Lewis M, ed. Child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:382–394.

8 Lamb M, Hwang C, Frodi A, Frodi M. Security of mother and father infant attachment and its relation to sociability with strangers in traditional and nontraditional Swedish families. Infant Behav Dev. 1982;5:355–367.

9 Bretherton I, Thompson RH, Lincoln N. Open communication and internal working models: their role in the development of attachment relationships. In: Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1988. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1990:57–113.

10 Belsky J, Lerner R, Spanier G. The child in the family. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

11 Chess S, Thomas A. Temperamental individuality from childhood to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1977;16:218–226.

12 Buss AH, Plomin R. Theory and measurement of EAS. Temperament: early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1984.

13 Strelau J. Emotion as a key concept in temperament research. J Res Pers. 1987;21:510–528.

14 Stifter CA, Fox NA. Infant reactivity: Physiological correlates of newborn and 5-month temperament. Dev Psych. 1990;26:582–588.

15 Kagan J, Snidman N. Temperamental factors in human development. Am Psychol. 1991;46:856–862.

16 Kain Z, Mayes L. Anxiety in children during the perioperative period. In: Borestein MH, Genevro JL, eds. Child development and behavioral pediatrics. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996:85–103.

17 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA. Preoperative psychological preparation of the child for surgery: an update. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:597–614.

18 Burton L. Anxiety relating to illness and treatment. In: Verma VP, ed. Anxiety in children. New York: Methuen Croom Helm; 1984:151–172.

19 Fell D, Derbyshire DR, Maile CJD, et al. Measurement of plasma catecholamine concentrations. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:770–774.

20 Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Alexander GM, Pincus S, Mayes LC. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated-measures design. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:417–422.

21 Williams JGL. Psychophysiological responses to anesthesia and operation. JAMA. 1968;203:127–129.

22 Williams JG, Jones JR, Williams B. A physiological measure of preoperative anxiety. Psychosom Med. 1969;31:522–527.

23 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, O’Connor TZ, Cicchetti DV. Preoperative anxiety in children. Predictors and outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 1996;150:1238–1245.

24 Vetter TR. The epidemiology and selective identification of children at risk for preoperative anxiety reactions. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:96–99.

25 Brophy CJ, Erickson MT. Children’s self-statements and adjustment to elective outpatient surgery. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11:13–16.

26 Lumley MA, Melamed BG, Abeles LA. Predicting children’s presurgical anxiety and subsequent behavior changes. J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:481–497.

27 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Weisman SJ, Hofstadter MB. Social adaptability, cognitive abilities, and other predictors for children’s reactions to surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:549–554.

28 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caramico LA. Preoperative preparation in children: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8:508–514.

29 Messeri A, Caprilli S, Busoni P. Anaesthesia induction in children: a psychological evaluation of the efficiency of parents’ presence. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:551–556.

30 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, Nelson W, Mayes LC. Predicting which child-parent pair will benefit most from parental presence during induction of anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:81–84.

31 Cassady FJ, Kain ZN. Preoperative preparation for parents of pediatric surgery patients. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2000;1:67–71.

32 Litman RS, Berger AA, Chhibber A. An evaluation of preoperative anxiety in a population of parents of infants and children undergoing ambulatory surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:443–447.

33 McCann ME, Kain ZN. The management of preoperative anxiety in children: an update. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:98–105.

34 Pruitt S, Elliott C, Johnston M, Wallace L. Paediatric procedures. In: Johnston ME, ed. Stress and medical procedures. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1990:157–174.

35 Melamed BG, Ridley-Johnson R. Psychological preparation of families for hospitalization. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1988;9:96–102.

36 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. Child life programs. Pediatrics. 1993;91:671–673.

37 Vernon D. The psychological responses of children to hospitalization and illness. Springfield, Ill.: C. C. Thomas Books; 1965.

38 Melamed BG, Siegel LJ. Reduction of anxiety in children facing hospitalization and surgery by use of filmed modeling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43:511–521.

39 O’Byrne K, Peterson L, Saldana L. Survey of pediatric hospitals’ preparation programs: Evidence of the impact of health psychology research. Health Psychol. 1997;16:147–154.

40 Kain ZN. Preoperative preparation and premedication of the pediatric patient. Probl Anesth. 1998;10:434–443.

41 Melamed BG, Siegel LJ, Franks CM, Evans FJ. Psychological preparation for hospitalization. In: Melamed BG, ed. Behavioral medicine: practical applications in health care. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1980:307–355.

42 Melamed BG, Dearborn M, Hermecz DA. Necessary considerations for surgery preparation: age and previous experience. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:517–525.

43 Faust J, Melamed B. Influence of arousal, previous experience, and age on surgery preparation of same day of surgery and in-hospital pediatric patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:359–365.

44 Kain ZN. Perioperative information and parental anxiety: the next generation. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:237–239.

45 Cassady JF, Jr., Wysocki TT, Miller KM, Cancel DD, Izenberg N. Use of a preanesthetic video for facilitation of parental education and anxiolysis before pediatric ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:246–250.

46 Saile H, Burgmeier R, Schmidt LR. A meta-analysis of studies on psychological preparation of children facing medical procedures. Psychol Health. 1988;2:107–132.

47 Blount R, Bachanas P, Powers S, et al. Training children to cope and parents to coach them during routine immunizations: effects on child, parent and staff behaviors. Behav Ther. 1992;23:689–705.

48 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:65–74.

49 Fortier MA, Blount RL, Wang SM, Mayes LC, Kain ZN. Analysing a family-centred preoperative intervention programme: a dismantling approach. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:713–718.

50 Bauchner H, Vinci R, Waring C. Pediatric procedures: do parents want to watch? Pediatrics. 1989;84:907–909.

51 Henderson MA, Baines DB, Overton JH. Parental attitudes to presence at induction of paediatric anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993;21:324–327.

52 Braude N, Ridley SA, Summer E. Parents and paediatric anaesthesia: a prospective survey of parental attitudes to their presence at induction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:41–44.

53 Ryder I, Spargo P. Parents in the anesthetic room: a questionnaire survey of parents’ reactions. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:977–979.

54 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Wang SM, et al. Parental intervention choices for children undergoing repeated surgeries. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:970–975.

55 Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Kerns RD, Ng D. Motivation and maternal presence during induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:478–483.

56 Vessey JA, Bogetz MS, Caserza CL, Liu KR, Cassidy MD. Parental upset associated with participation in induction of anaesthesia in children. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:276–280.

57 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia: physiological effects on parents. Anesthesiology 2003. 2003;98:58–64.

58 Wang SM, Maranets I, Weinberg ME, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN. Parental auricular acupuncture as an adjunct for parental presence during induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1399–1404.

59 Shaw EG, Routh DK. Effect of mother presence on children’s reaction to aversive procedures. J Pediatr Psychol. 1982;7:33–42.

60 Bowie JR. Parents in the operating room. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:1192–1193.

61 Schofield NM, White JB. Interrelations among children, parents, premedication, and anaesthetists in paediatric day stay surgery. BMJ. 1989;299:1371–1375.

62 Gauderer MW, Lorig JL, Eastwood DW. Is there a place for parents in the operating room? J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:705–706.

63 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Bell C, et al. Premedication in the United States: a status report. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:427–432.

64 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Krivutza D, et al. Trends in the practice of parental presence during induction of anesthesia and the use of preoperative sedative premedication in the United States, 1995-2002: results of a follow-up national survey. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1252–1259.

65 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caramico LA, et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia. A randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1060–1067.

66 Bevan JC, Johnston C, Haig MJ, et al. Preoperative parental anxiety predicts behavioral and emotional responses to induction of anesthesia in children. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:177–182.

67 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Wang SM, Caramico LA, Hofstadter MB. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia versus sedative premedication: which intervention is more effective? Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1147–1156. discussion 9A-10A

68 Hannallah RS, Rosales JK. Experience with parents’ presence during anaesthesia induction in children. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1983;30:286–289.

69 Schulman JL, Foley JM, Vernon DT, Allan D. A study of the effect of the mother’s presence during anesthesia induction. Pediatrics. 1967;39:111–114.

70 Dahlquist LM, Gil KM, Armstrong FD, et al. Preparing children for medical examinations: the importance of previous medical experience. Health Psychol. 1986:249–259.

71 Caldwell-Andrews AA, Blount RL, Mayes LC, Kain ZN. Behavioral interactions in the perioperative environment: a new conceptual framework and the development of the perioperative child-adult medical procedure interaction scale. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1130–1135.

72 Egbert L, Battit G, Turndorf H, Beecher H. The value of the preoperative visit by an anesthetist. JAMA. 1963;185:553–555.

73 Alfidi R. Informed consent: a study of patient reaction. JAMA. 1971;216:1325–1329.

74 Miller S, Mangan C. Interacting effects of information and coping style in adapting to gynecologic stress: should the doctor tell all? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45:223–226.

75 Kerrigan DD, Thevasagayam RS, Woods TO, et al. Who’s afraid of informed consent? BMJ. 1993;306:298–300.

76 Kain Z, Hernandez Conte A, Kosarusavadi B, Lee M. Desire for information in adults patients: a cross sectional study. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:467–472.

77 Kain ZN, Wang SM, Caramico LA, Hofstadter M, Mayes LC. Parental desire for perioperative information and informed consent: a two-phase study. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:299–306.

78 Inglis S, Farnill D. The effects of providing preoperative statistical anaesthetic-risk information. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993;21:799–805.

79 Fortier MA, Chorney JM, Rony RY, et al. Children’s desire for perioperative information. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1085–1090.

80 Miller SM. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease. Implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76:167–177.

81 Martin SR, Chorney JM, Tan ET, et al. Changing healthcare providers’ behavior during pediatric inductions with an empirically based intervention. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:18–27.

82 Blount RL, Corbin S, Sturges J, et al. The relationship between adults’ behavior and child coping and distress during BMA/LP procedures: a sequential analysis. Behav Ther. 1989;20:585–601.

83 Manimala M, Blount R, Cohen L. The effects of parental reassurance versus distraction on child distress and coping during immunizations. Child Health Care. 2000;29:161–177.

84 Cohen L, Blount R, Panopoulos G. Nurse coaching and cartoon distraction: an effective and practical intervention to reduce child, parent and nurse distress during immunizations. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:355–370.

85 Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely S. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: an abbreviated Cochrane review. J Pediatr Psychol 2008. 2008;33:842–854.

86 Sadhasivam S, Cohen LL, Szabova A, et al. Real-time assessment of perioperative behaviors and prediction of perioperative outcomes. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:822–826.

87 Chorney JM, Torrey C, Blount RL, et al. Healthcare provider and parent behavior and children’s coping and distress at anesthesia induction. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1290–1296.

88 Chorney JM, Kain ZN. Behavioral analysis of children’s response to induction of anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1434–1440.

89 Blount R, Bunke V, Zaff J. Bridging the gap between explicative and treatment research: a model and practical implications. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2000;7:79–90.

90 Blount RL, Zempsky WT, Jaaniste T, et al. Management of pain and distress due to medical procedures. In: Roberts M, Steele R, eds. Handbook of pediatric psychology. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2009:171–188.

91 Kain ZN, Ferris CA, Mayes LC, Rimar S. Parental presence during induction of anaesthesia: practice differences between the United States and Great Britain. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:187–193.

92 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Wang SM, et al. Parental presence and a sedative premedicant for children undergoing surgery: a hierarchical study. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:939–946.

93 Janis IL. Psychological stress: psychoanalytic and behavioral studies of surgical patients. New York: Wiley; 1958.

94 Johnson JE, Leventhal H, Dabbs JM, Jr. Contribution of emotional and instrumental response processes in adaptation to surgery. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;20:55–64.

95 Johnston M, Fisher S, Reason J. Impending surgery. In: Fisher S, Reason J, eds. Handbook of life stress. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1988:79–100.

96 Newman S, Fitzpatrick R, Hinton J, et al. Anxiety, hospitalization, and surgery. In: Fitzpatrick R, ed. The experience of illness. London: Tavistock Publications; 1984:132–153.

97 Pick B, Molloy A, Hinds C, Pearce S, Salmon P. Post-operative fatigue following coronary artery bypass surgery: relationship to emotional state and to the catecholamine response to surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:599–607.

98 Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R. Psychological influences on surgical recovery. Perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol. 1998;53:1209–1218.

99 Johnston M. Pre-operative emotional states and post-operative recovery. Adv Psychosom Med. 1986;15:1–22.

100 Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Alexander GA, Pincus S, Mayes LC. Predictors for postoperative pain in women undergoing surgery: a repeated measures design. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:417–422.

101 Kain ZN. Postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes in children: incidence, risks factors and interventions. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2000;51:217–226.

102 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews A, Maranets I, et al. Preoperative anxiety, emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors: are they related? A new conceptual framework. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1648–1654.

103 Fortier MA, Del Rosario AM, Martin SR, Kain ZN. Perioperative anxiety in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:318–322.

104 Martinez-Urrutia A. Anxiety and pain in surgical patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43:437–442.

105 Lindeman CA, Stetzer SL. Effect of preoperative visits by operating room nurses. Nurs Res. 1973;22:4–16.

106 Egbert L, E. BG, E. WC, K. BM. Reduction of postoperative pain by encouragement and instruction of patients. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:825–827.

107 George JM, Scott DS. The effects of psychological factors on recovery from surgery. J. Am Dent Assoc. 1982;105:251–258.

108 Ray C, Fitzgibbon G. Stress arousal and coping with surgery. Psychol Med. 1981;11:741–746.

109 Taenzer P, Melzack R, Jeans ME. Influence of psychological factors on postoperative pain, mood and analgesic requirements. Pain. 1986;24:331–342.

110 Scott LE, Clum GA, Peoples JB. Preoperative predictors of postoperative pain. Pain. 1983;15:283–293.

111 Lim AT, Edis G, Kranz H, et al. Postoperative pain control: contribution of psychological factors and transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Pain. 1983;17:179–188.

112 George JM, Scott DS, Turner SP, Gregg JM. The effects of psychological factors and physical trauma on recovery from oral surgery. J Behav Med. 1980;3:291–310.

113 Wallace LM. Pre-operative state anxiety as a mediator of psychological adjustment to and recovery from surgery. Br J Med Psychol. 1986;59:253–261.

114 Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Tait AR. A prospective cohort study of emergence agitation in the pediatric postanesthesia care unit. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1625–1630.

115 Aono J, Ueda W, Kataoka Y, Manabe M. Differences in hormonal responses to preoperative emotional stress between preschool and school children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:229–231.

116 Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1648–1654.

117 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caldwell-Andrews AA, et al. Sleeping characteristics of children undergoing outpatient elective surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1093–1101.

118 Kokki H, Ahonen R. Pain and activity disturbance after paediatric day case adenoidectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 1997;7:227–231.

119 Kotiniemi LH, Ryhanen PT, Valanne J, et al. Postoperative symptoms at home following day-case surgery in children: a multicentre survey of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:963–969.

120 Kotiniemi LH, Ryhanen PT, Moilanen IK. Behavioural changes in children following day-case surgery: a 4-week follow-up of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:970–976.

121 Kotiniemi LH, Ryhanen PT, Moilanen IK. Behavioural changes following routine ENT operations in two-to-ten-year-old children. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:45–49.

122 Vernon DT, Schulman JL, Foley JM. Changes in children’s behavior after hospitalization. Am J Dis Child. 1966;111:581–593.

123 Kain Z, Mayes L, Caramico L, Hofstadter M. Distress during induction of anesthesia and postoperative behavioral outcomes. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1042–1047.

124 Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Wang SM, Hofstadter MB. Postoperative behavioral outcomes in children: effects of sedative premedication. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:758–765.

125 Parris WC, Matt D, Jamison RN, Maxson W. Anxiety and postoperative recovery in ambulatory surgery patients. Anesth Prog. 1988;35:61–64.

126 Williams JGL, Jones JR, Workhoven MN, Williams B. The psychological control of preoperative anxiety. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:50–54.

127 Goldmann L, Ogg TW, Levey AB. Hypnosis and daycase anaesthesia. A study to reduce pre-operative anxiety and intra-operative anaesthetic requirements. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:466–469.

128 Maranets I, Kain Z. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1346–1351.

129 Watcha MF, Jones MB, Lagueruela RG, Schweiger MS, White PF. Comparison of ketorolac and morphine as adjuvants during pediatric surgery. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:368–372.

130 Wang SM, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative nausea and vomiting in children: is there an association? Anesth Analg. 2000;90:571–575.