Perinatal medicine

Some definitions used in perinatal medicine are:

• Stillbirth – fetus born with no signs of life ≥24 weeks of pregnancy

• Perinatal mortality rate – stillbirths + deaths within the first week per 1000 live births and stillbirths

• Neonatal mortality rate – deaths of liveborn infants within the first 4 weeks after birth per 1000 live births

• Neonate – infant ≤28 days old

• Preterm – gestation <37 weeks of pregnancy

• Term – 37–41 weeks of pregnancy

• Post-term – gestation ≥42 weeks of pregnancy

• Low birthweight (LBW) – <2500 g

• Very low birthweight (VLBW) – <1500 g

• Extremely low birthweight (ELBW) – <1000 g

• Small for gestational age – birthweight <10th centile for gestational age

• Large for gestational age – birthweight >90th centile for gestational age.

Pre-pregnancy care

• Smoking reduces birthweight, which may be of critical importance if born preterm. On average, the babies of smokers weigh 170 g less than those of non-smokers, but the reduction in birthweight is related to the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. The infant has a greater risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

• Pre-pregnancy folic acid supplements reduce the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus. Low-dose folic acid supplementation is recommended for all women planning a pregnancy. A higher dose is recommended for women with, or have a close relative with, a previously affected fetus.

• Any long-term conditions, such as diabetes and epilepsy, must be reviewed and management changed if necessary.

• Certain medications such as retinoids, warfarin and sodium valproate must be avoided because of teratogenic effects.

• Alcohol ingestion and drug abuse (opiates, cocaine) may damage the fetus.

• Congenital rubella is preventable by maternal immunisation before pregnancy.

• Exposure to toxoplasmosis should be minimised by avoiding eating undercooked meat and by wearing gloves when handling cat litter.

• Listeria infection can be acquired from eating unpasteurised dairy products, soft ripened cheeses, e.g. brie, camembert and blue veined varieties, patés and ready-to-eat poultry, unless thoroughly re-heated.

• Eating liver during pregnancy is best avoided as it contains a high concentration of vitamin A.

• the mother is older (if she is >35 years old, the risk of Down syndrome is >1 in 380), although screening is now available for all mothers

• there is previous congenital abnormality

• there is a family history of an inherited disorder

• the parents are identified as carriers of an autosomal recessive disorder, e.g. thalassaemia

Antenatal diagnosis

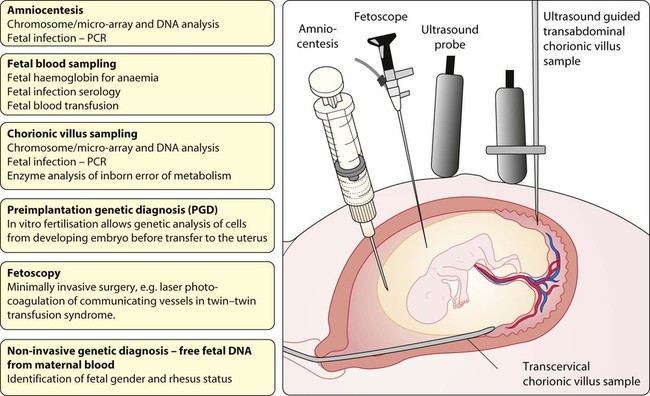

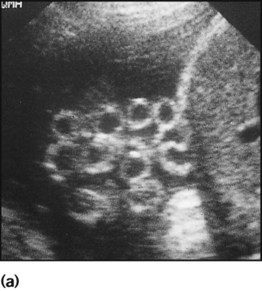

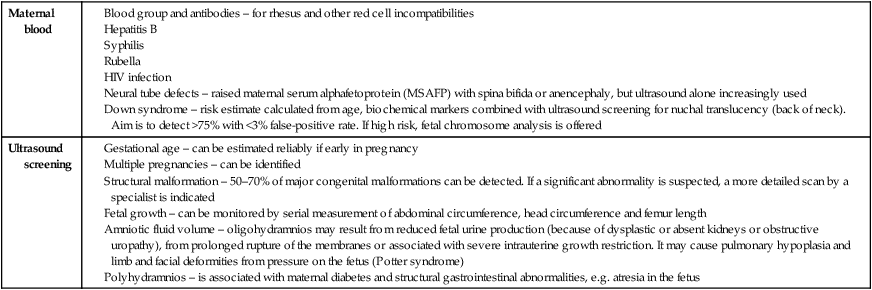

Antenatal diagnosis has become available for an increasing number of disorders. Screening tests performed on maternal blood and ultrasound of the fetus are listed in Box 9.1. The main diagnostic techniques for antenatal diagnosis are maternal serum screening, detailed ultrasound scanning, chorionic villus sampling (at >10 weeks of pregnancy) and amniocentesis (>15 weeks) (Fig. 9.1). In some rare conditions, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) allows genetic analysis of cells from a developing embryo before transfer to the uterus. The structural malformations and other lesions which can be identified on ultrasound are listed in Box 9.2, with an example in Figure 9.2.

Antenatal screening for disorders affecting the mother or fetus allows:

• reassurance where disorders are not detected

• optimal obstetric management of the mother and fetus

• interventions for a limited number of conditions, such as relieving bladder obstruction or draining pleural effusions, to improve perinatal outcome

• counselling and neonatal management to be planned in advance

• the option of termination of pregnancy to be offered for severe disorders affecting the fetus (see Case History 9.1) or compromising maternal health.

Fetal medicine

The fetus can sometimes be treated by giving medication to the mother. Examples include:

• Glucocorticoid therapy before preterm delivery accelerates lung maturity and surfactant production. This has been tested in over 15 randomised trials and markedly reduces the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (relative risk 0.66), of intraventricular haemorrhage (relative risk 0.54) and neonatal mortality (relative risk 0.69) in preterm infants. For optimal effect, a completed course needs to be given at least 24 h before delivery.

• Digoxin or flecainide can be given to the mother to treat fetal supraventricular tachycardia.

There are a few conditions where therapy can be given to the fetus directly:

• Rhesus isoimmunisation. Severely affected fetuses become anaemic and may develop hydrops fetalis, with oedema and ascites. Infants at risk are identified by maternal antibody screening. Regular ultrasound of the fetus is performed to detect fetal anaemia non-invasively using Doppler velocimetry of the fetal middle cerebral artery. Fetal blood transfusion via the umbilical vein may be required regularly from about 20 weeks’ gestation. The incidence of rhesus haemolytic disease has fallen markedly since anti-D immunisation of mothers was introduced but hydrops fetalis is still seen due to other red blood cell antibodies such as Kell.

• Perinatal isoimmune thrombocytopenia. This condition is analogous to rhesus isoimmunisation but involves maternal antiplatelet antibodies crossing the placenta. It is rare, affecting about 1 in 5000 births. Intracranial haemorrhage secondary to fetal thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 25%. The problem may be anticipated if there was a previously affected infant, when prenatal intravenous immunoglobulin can be given or repeated intrauterine platelet transfusions performed.

Fetal surgery

• Catheter shunts inserted under ultrasound guidance. This is to drain fetal pleural effusions (pleuro-amniotic shunts), often from a chylothorax (lymphatic fluid) or congenital cystic adenomatous malformation of the lung. One end of a looped catheter lies in the chest, the other end in the amniotic cavity.

• Laser therapy to ablate placental anastomoses which lead to the twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS)

• Intrauterine shunting for obstruction to urinary outflow as with posterior urethral valves

• Dilatation of stenotic heart valves via a transabdominal catheter inserted under ultrasound guidance into the fetal heart. Results appear promising

• Endotracheal balloon occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia, as tracheal obstruction in utero may promote lung growth

• Surgical correction by hysterotomy. This is when the uterus is opened at 22–24 weeks’ gestation. It has been performed in a few specialist centres for spina bifida but may precipitate preterm delivery and its efficacy remains highly uncertain. Results of fetal surgery to close spina bifida suggest that hydrocephalus may be reduced but does not improve the prognosis of the spinal lesion.

Obstetric conditions affecting the fetus

Pre-eclampsia

Multiple births

The main problems for the infant associated with multiple births are:

• Preterm labour. The median gestation for twins is 37 weeks, for triplets 34 weeks and for quads 32 weeks. Preterm delivery is the most important cause of the greater perinatal mortality of multiple births, especially for triplets and higher-order pregnancies. When a higher-order pregnancy is identified, embryo reduction may be offered.

• Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Fetal growth in one or more fetuses may deteriorate and needs to be monitored regularly.

• Congenital abnormalities. These occur twice as frequently as in a singleton, but the risk is increased four-fold in monochorionic twins.

• Twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) in monochorionic twins (shared placenta). May cause extreme preterm delivery, fetal death and discrepancy in growth.

• Complicated deliveries, e.g. due to malpresentation of the second twin at vaginal delivery.

Finding sufficient intensive care cots for preterm multiple births can be problematic.

• Practical – with their care and housework (requires about 200 h/week for triplets in infancy!)

• Emotional and physical exhaustion

• Increased behavioural problems in the infants and their siblings. While being a multiple birth may provide companionship, affection and stimulation between each other, it may also engender domination, dependency and jealousy.

There are local and national support groups for parents of multiple births.

Maternal conditions affecting the fetus

Diabetes mellitus

Fetal problems associated with maternal diabetes are:

• Congenital malformations. Overall, there is a 6% risk of congenital malformations, a three-fold increase compared with the non-diabetic population. The range of anomalies is similar to that for the general population, apart from an increased incidence of cardiac malformations, sacral agenesis (caudal regression syndrome) and hypoplastic left colon, although the latter two conditions are rare. Studies show that good diabetic control periconceptionally reduces the risk of congenital malformations.

• Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). There is a three-fold increase in growth restriction in mothers with long-standing microvascular disease.

• Macrosomia (Fig. 9.4). Maternal hyperglycaemia causes fetal hyperglycaemia as glucose crosses the placenta. As insulin does not cross the placenta, the fetus responds with increased secretion of insulin, which promotes growth by increasing both cell number and size. About 25% of such infants have a birthweight greater than 4 kg compared with 8% of non-diabetics. The macrosomia predisposes to cephalopelvic disproportion, birth asphyxia, shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury.

• Hypoglycaemia. Transient hypoglycaemia is common during the first day of life from fetal hyperinsulinism, but can often be prevented by early feeding. The infant’s blood glucose should be closely monitored during the first 24 h and hypoglycaemia treated

• Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). More common as lung maturation is delayed

• Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hypertrophy of the cardiac septum occurs in some infants. It regresses over several weeks but may cause heart failure from reduced left ventricular function

• Polycythaemia (venous haematocrit >0.65). Makes the infant look plethoric. Treatment with partial exchange transfusion to reduce the haematocrit and normalise viscosity may be required.

Maternal drugs affecting the fetus

Relatively few drugs are known definitely to damage the fetus (Table 9.1), but it is clearly advisable for pregnant women to avoid taking medicines unless it is essential. While the teratogenicity of a drug may be recognised if it causes malformations which are severe and distinctive, as with limb shortening following thalidomide ingestion, milder and less distinctive abnormalities may go unrecognised.

Table 9.1

Maternal medication which may adversely affect the fetus

| Medication | Adverse effect on fetus |

| Anticonvulsant therapy with carbamazepine, valproic acid (sodium valproate) or hydantoins (phenytoin) | Fetal carbamazepine/valproate/hydantoin syndrome – midfacial hypoplasia, CNS, limb and cardiac malformations, developmental delay |

| Cytotoxic agents | Congenital malformations |

| Diethylstilboestrol (DES) | Clear-cell adenocarcinoma of vagina and cervix |

| Iodides/propylthiouracil | Goitre, hypothyroidism |

| Lithium | Congenital heart disease |

| Tetracycline | Enamel hypoplasia of the teeth |

| Thalidomide | Limb shortening (phocomelia) |

| Vitamin A and retinoids | Increased spontaneous abortions, abnormal face |

| Warfarin | Interferes with cartilage formation (nasal hypoplasia and epiphyseal stippling); cerebral haemorrhages and microcephaly |

Alcohol and smoking

Excessive alcohol ingestion during pregnancy is sometimes associated with the ‘fetal alcohol syndrome’. Its clinical features are growth restriction, characteristic face (Fig. 9.5), developmental delay and cardiac defects (up to 70%). The effects of less severe ingestion and binge-drinking remain uncertain but may affect growth and development, and mothers are advised to avoid alcohol (Department of Health, London, UK). Maternal cigarette smoking is associated in the fetus with an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth, a reduction in birthweight and IUGR (see pre-pregnancy care, earlier in this chapter).

Drugs given during labour

Potential adverse effects to the fetus of drugs given during labour are:

• Opioid analgesics/anaesthetic agents. May suppress respiration at birth

• Epidural anaesthesia. May cause maternal pyrexia during labour. It is often difficult to differentiate this from fever caused by an infection. There is an increase in the rate of forceps deliveries

• Sedatives, e.g. diazepam. May cause sedation, hypothermia and hypotension in the newborn

• Oxytocin and prostaglandin F2. May cause hyperstimulation of the uterus leading to fetal hypoxia. It is also associated with a small increase in bilirubin levels in the neonate

• Intravenous fluids. May cause neonatal hyponatraemia unless they contain an adequate concentration of sodium.

Congenital infections

Rubella

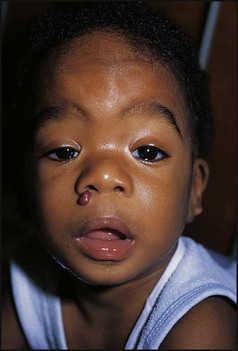

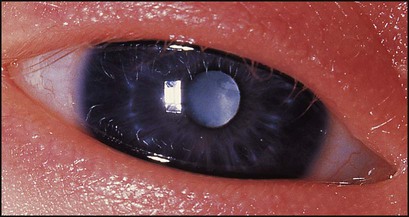

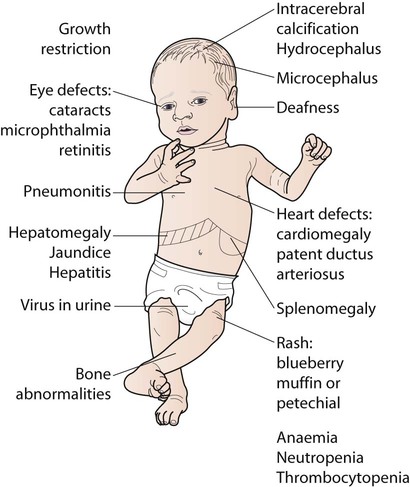

The diagnosis of maternal infection must be confirmed serologically as clinical diagnosis is unreliable. The risk and extent of fetal damage are mainly determined by the gestational age at the onset of maternal infection. Infection before 8 weeks’ gestation causes deafness, congenital heart disease and cataracts in over 80% (Fig. 9.6a). About 30% of fetuses of mothers infected at 13–16 weeks’ gestation have impaired hearing; beyond 18 weeks’ gestation, the risk to the fetus is minimal. Viraemia after birth continues to damage the infant. Tests used to confirm the diagnosis are shown in Box 9.3. The range of clinical features characteristic of congenital infections is shown in Figure 9.6b.

Cytomegalovirus

• 90% are normal at birth and develop normally

• 5% have clinical features at birth, such as hepatosplenomegaly and petechiae (Fig. 9.6b), most of whom will have neurodevelopmental disabilities such as sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral palsy, epilepsy and cognitive impairment

• 5% develop problems later in life, mainly sensorineural hearing loss.

Toxoplasmosis

Acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite, may result from the consumption of raw or undercooked meat and from contact with the faeces of recently infected cats. In the UK, fewer than 20% of pregnant women have had past infection, in contrast to 80% in France and Austria. Transplacental infection may occur during the parasitaemia of a primary infection, and about 40% of fetuses become infected. In the UK, the incidence of congenital infection is only about 0.1 per 1000 live births. Most infected infants are asymptomatic. About 10% have clinical manifestations (Fig. 9.6b), of which the most common are:

Varicella zoster

• in the first half of pregnancy (<20 weeks), when there is a <2% risk of the fetus developing severe scarring of the skin and possibly ocular and neurological damage and digital dysplasia

• within 5 days before or 2 days after delivery, when the fetus is unprotected by maternal antibodies and the viral dose is high. About 25% develop a vesicular rash. The illness has a mortality as high as 30%.

Syphilis

Congenital syphilis is rare in the UK. The clinical features are shown in Figure 9.6b. Those specific to congenital syphilis include a characteristic rash on the soles of the feet and hands and bone lesions. If mothers with syphilis identified on antenatal screening are fully treated 1 month or more before delivery, the infant does not require treatment and has an excellent prognosis. If there is any doubt about the adequacy of maternal treatment, the infant should be treated with penicillin.

Adaptation to extrauterine life

In the fetus, the lungs are filled with fluid, and oxygen is supplied by the placenta. The blood vessels that supply and drain the lungs are constricted (high pulmonary vascular resistance), so most blood from the right side of the heart bypasses the lungs and flows through the ductus arteriosus into the aorta, and some flows across the foramen ovale (Fig. 9.7). Shortly before and during labour, lung liquid production is reduced. During descent through the birth canal, the infant’s chest is squeezed and some lung liquid drained. Multiple stimuli, including thermal, tactile and hormonal (with a particularly dramatic increase in catecholamine levels), initiate breathing. On average, the first breath occurs 6 s after delivery. Lung expansion is generated by intrathoracic negative pressure and a functional residual capacity is established. The mean time to establish regular breathing is 30 s. Once the infant gasps, the majority of the remaining lung fluid is absorbed into the lymphatic and pulmonary circulation.

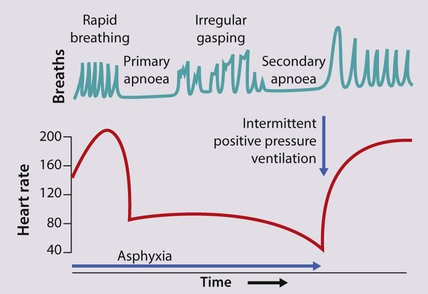

Some infants do not breathe at birth. This may be due to asphyxia, when the fetus experiences a lack of oxygen during labour and/or delivery. It does not necessarily mean that the brain has been injured but asphyxia can lead to brain injury or death. A fetus deprived of oxygen in utero will attempt to breathe, but if this is unsuccessful (as it will be in utero), it will then become apnoeic (primary apnoea), during which time the heart rate is maintained. If oxygen deprivation continues, primary apnoea is followed by irregular gasping and then a second period of apnoea (secondary or terminal apnoea), when the heart rate and blood pressure fall. If delivered at this stage, the infant will only recover if help with lung expansion is provided, e.g. by positive pressure ventilation by mask or tracheal tube (Fig. 9.8).

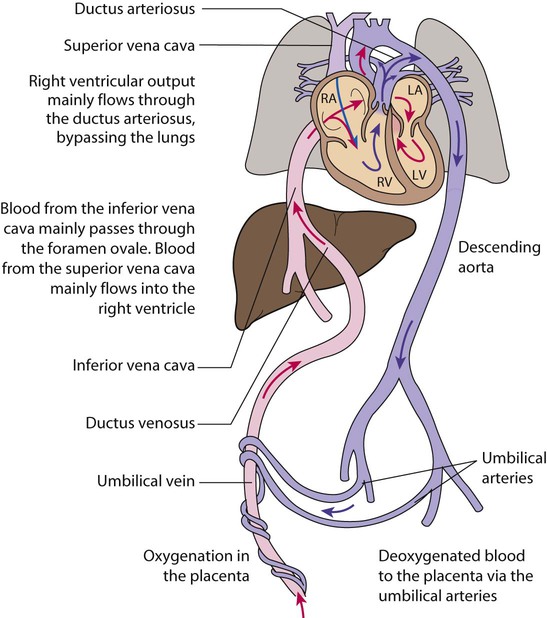

The Apgar score is used to describe a baby’s condition at 1 and 5 min after delivery (Table 9.2). It is also measured at 5-min intervals thereafter, if the infant’s condition remains poor. The most important components are the heart rate and respiration.

Table 9.2

| Score | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Heart rate | Absent | <100 beats/min | ≥100 beats/min |

| Respiratory effort | Absent | Gasping or irregular | Regular, strong cry |

| Muscle tone | Flaccid | Some flexion of limbs | Well flexed, active |

| Reflex irritability | None | Grimace | Cry, cough |

| Colour | Pale/blue | Body pink, extremities blue | Pink |

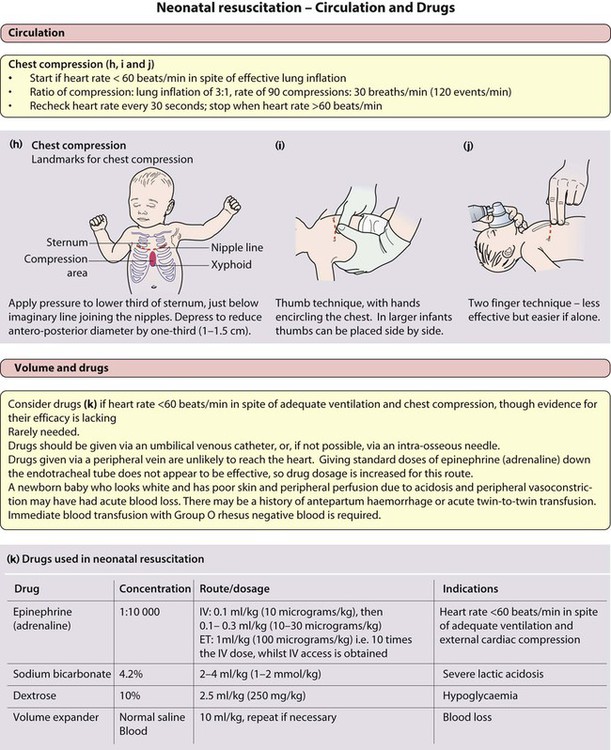

Neonatal resuscitation

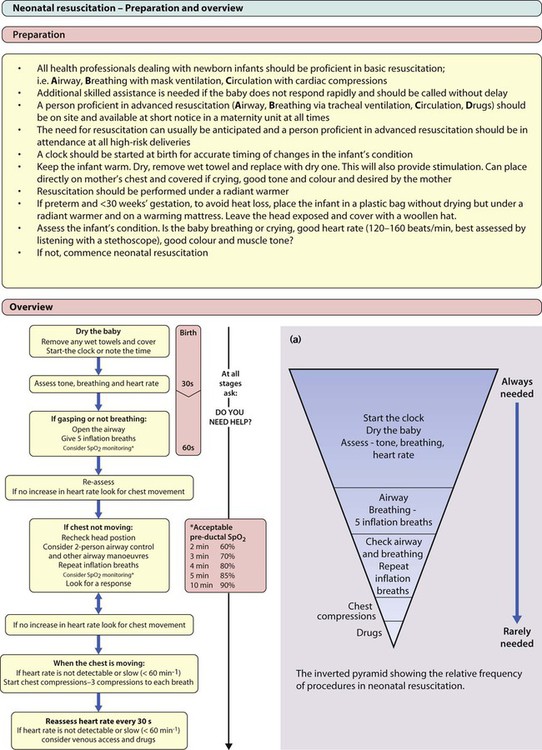

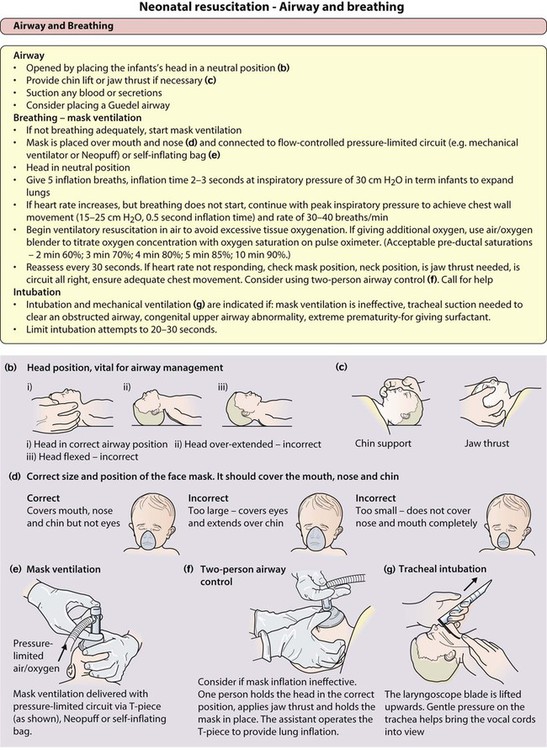

Most infants do not require any resuscitation. Shortly after birth, the baby will take a breath or cry, establish regular breathing and become pink. The baby can be handed directly to his or her mother, and covered with a warm towel to avoid becoming cold. However, a newborn infant who does not establish normal respiration directly will need to be transferred to a resuscitation table for further assessment (Fig. 9.9a). There should be an overhead radiant heater and the infant should be dried and partially covered and kept warm. Suction of the mouth and nose is normally unnecessary and vigorous suction of the back of the throat may provoke bradycardia from vagal stimulation. If the infant’s breathing in the first minute of life is irregular or shallow, but the heart rate is satisfactory (>100 beats/min), breathing is encouraged with airway opening manoeuvres.

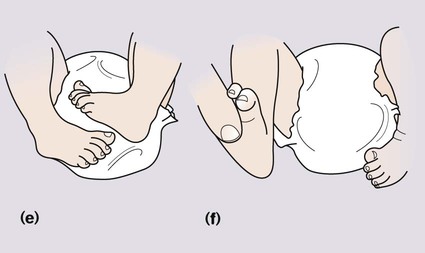

If the infant does not start to breathe, or if the heart rate drops below 100 beats/min, airway positioning and lung inflation by breathing by mask ventilation are started (Fig. 9.9b–f). If the baby’s condition does not improve promptly, or if the infant is clearly in very poor condition at birth, additional assistance should be summoned immediately while continuing to maintain ventilation. If an attendant has the appropriate skills, tracheal intubation can be performed (Fig. 9.9g).

• Displaced tube: often in the oesophagus or right main bronchus

If at any time the heart rate drops below 60 beats/min, provided adequate breathing has been achieved, chest compressions should be given (Fig. 9.9h–j). If the response to ventilation and chest compression remains inadequate, drugs should be given (Fig. 9.9k). Evidence for their efficacy is very poor.

Size at birth

Definitions

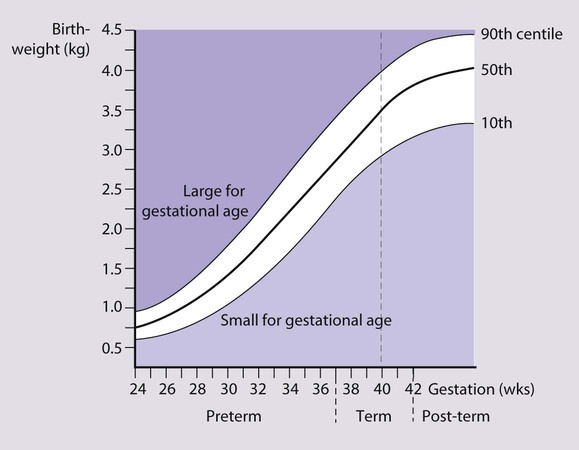

Babies with a birthweight below the 10th centile for their gestational age are called small for gestational age or small-for-dates (Fig. 9.10). The majority of these infants are normal, but small. The incidence of congenital abnormalities and neonatal problems is higher in those whose birthweight falls below the second centile (approximately two standard deviations (SD) below the mean), and some authorities restrict the term to this group of babies. An infant’s birthweight may also be low because of preterm birth, or because the infant is both preterm and small for gestational age.

Patterns of growth restriction

Growth restriction in both the fetus and infant has traditionally been classified as symmetrical or asymmetrical. In the more common asymmetrical growth restriction, the weight or abdominal circumference lies on a lower centile than that of the head. This occurs when the placenta fails to provide adequate nutrition late in pregnancy but brain growth is relatively spared at the expense of liver glycogen and skin fat (Fig. 9.11). This form of growth restriction is associated with uteroplacental dysfunction secondary to maternal pre-eclampsia, multiple pregnancy, maternal smoking or it may be idiopathic. These infants rapidly put on weight after birth.

Monitoring the growth-restricted fetus

The fetus with IUGR is at risk from:

• reduced growth in femur length and abdominal circumference

• abnormal umbilical artery Doppler waveforms – absent or reversed end diastolic flow velocity

• redistribution of blood flow in the fetus – increased to the brain, reduced to gastrointestinal tract, liver, skin and kidneys

• reduced amniotic fluid volume

• reduced fetal movements and abnormal CTG (cardiotocography).

Large-for-gestational-age infants

• Birth asphyxia from a difficult delivery

• Breathing difficulty from an enlarged tongue in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome

• Birth trauma, especially from shoulder dystocia at delivery (difficulty delivering the shoulders from impaction behind maternal symphysis pubis)

Routine examination of the newborn infant

• detect congenital abnormalities not already identified at birth, e.g. congenital heart disease, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

• check for potential problems arising from maternal disease or familial disorders

• provide an opportunity for the parents to discuss any questions about their baby.

Before approaching the mother and baby, the obstetric and neonatal notes must be checked to identify relevant information. The examination (Fig. 9.12) should be performed with the mother or ideally both parents present. Many findings in the newborn resolve spontaneously (Box 9.5, Fig. 9.13). Common significant abnormalities detectable at birth are listed in Box 9.6. A serious congenital anomaly is present at birth in about 10–15/1000 live births (Table 9.3). In addition, many congenital anomalies, especially of the heart, present clinically at a later age.

Table 9.3

Prevalence of serious congenital anomalies per 1000 live births (England and Wales)

| Anomaly | Prevalence |

| Congenital heart disease | 6–8 (0.8 on the first day of life) |

| Developmental dysplasia of the hip | 1.5 (but about 6/1000 have an abnormal initial clinical examination) |

| Talipes | 1.0 |

| Down syndrome | 1.0 |

| Cleft lip and palate | 0.8 |

| Urogenital (hypospadias, undescended testes) | 1.2 |

| Spina bifida/anencephaly | 0.1 |

Median measurements:

• birthweight 3.5 kg;

• head circumference 35 cm;

• length 50 cm.

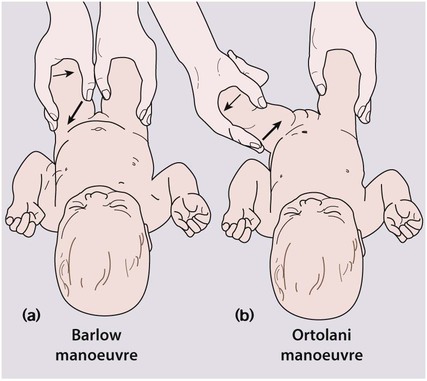

Testing for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

To test for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), also called congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH), the infant needs to be relaxed, as kicking or crying results in tightening of the muscles around the hip and prevents satisfactory examination. The pelvis is stabilised with one hand. With the other hand, the examiner’s middle finger is placed over the greater trochanter and the thumb around the distal medial femur. The hip is held flexed and adducted. The femoral head is gently pushed downwards. If the hip is dislocatable, the femoral head will be pushed posteriorly out of the acetabulum (Fig. 9.15a).

The next part of the examination is to see if the hip can be returned from its dislocated position back into the acetabulum. With the hip abducted, upward leverage is applied (Fig. 9.15b). A dislocated hip will return with a ‘clunk’ into the acetabulum. Ligamentous clicks without any movement of the head of femur are of no significance. It should also be possible to abduct the hips fully, but this may be restricted if the hip is dislocated. Clinical examination does not identify some infants who have hip dysplasia from lack of development of the acetabular shelf. DDH is more common in girls (six-fold increase), if there is a positive family history (20% of affected infants), if the birth is a breech presentation (30% of affected infants) or if the infant has a neuromuscular disorder.

Biochemical screening (Guthrie test)

• haemoglobinopathies (sickle cell and thalassaemia)

• MCAD (medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase) deficiency – a rare inborn error of mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism causing acute illness and hypoglycaemia following fasting, which may also present as an ALTE (acute life-threatening episode).

Screening for cystic fibrosis is performed by measuring the serum immunoreactive trypsin, which is raised if there is pancreatic duct obstruction. If raised, DNA analysis is also performed to reduce the false-positive rate (see Ch. 16).

Newborn hearing screening

Universal screening has been introduced in the UK to detect severe hearing impairment in newborn infants. Early detection and intervention improves speech and language. Evoked otoacoustic emission (EOAE) testing, when an earphone is placed over the ear and a sound is emitted which evokes an echo or emission from the ear if cochlear function is normal, is used as the initial screening test. If a normal test is not achieved, testing with automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) audiometry, using computer analysis of EEG waveforms evoked in response to a series of clicks, is performed, with referral to a paediatric audiologist if abnormal (see Ch. 3 for further details).