Pericardium and Extra-Cardiac Structures

Anatomy and Pathology

Enrique Pantin and F. Luke Aldo

There are so many things surrounding the heart that no one pays attention to!

It is all about the heart though, so who cares about all that other stuff. Right? Wrong!

The Pericardium

Surrounds, protects, supports, limits chamber dilation, and lubricates, allowing the free motion of the heart.

Surrounds, protects, supports, limits chamber dilation, and lubricates, allowing the free motion of the heart.

Provides entry and exit passages to the heart.

Provides entry and exit passages to the heart.

Is a medium-sized bag with lots of holes and tubes crossing it to enter or exit the heart:

Is a medium-sized bag with lots of holes and tubes crossing it to enter or exit the heart:

Upper abdominal aorta and its branches.

Upper abdominal aorta and its branches.

Trachea (yeah, we know you can’t see me but you know where I am because I don’t let you see other guys!).

Trachea (yeah, we know you can’t see me but you know where I am because I don’t let you see other guys!).

Spine, vertebral disks, and spinal cord (just bits of it can be seen).

Spine, vertebral disks, and spinal cord (just bits of it can be seen).

Stomach and its content or lack of it.

Stomach and its content or lack of it.

Other stuff like the tongue could be seen but it won’t be TEE but oral ultrasound!

Other stuff like the tongue could be seen but it won’t be TEE but oral ultrasound!

Starting from the esophageal entrance we can see the main neck vessels (the carotid arteries and internal jugular veins)

Starting from the esophageal entrance we can see the main neck vessels (the carotid arteries and internal jugular veins)

can be used to guide central line placement, though I would NOT recommend this in the awake patient!

can be used to guide central line placement, though I would NOT recommend this in the awake patient!

In the esophageal upper 1/3, we can see part or all of the arch vessels

In the esophageal upper 1/3, we can see part or all of the arch vessels

In the mid 1/3 of the esophagus, the trachea creates a blind spot, and we miss the distal ascending aorta, proximal arch, and proximal to mid left pulmonary artery, but we can see:

In the mid 1/3 of the esophagus, the trachea creates a blind spot, and we miss the distal ascending aorta, proximal arch, and proximal to mid left pulmonary artery, but we can see:

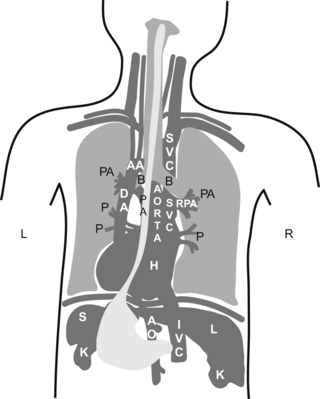

L = left and R = right; PA = pulmonary artery, P = pulmonary veins, H = heart, L = liver, S = spleen, and K = kidney.

Did you understand the drawing?, I didn’t… If you didn’t, don’t kill yourself over it, it is a pretty bad drawing. My partner did the drawing, so call him and let him know you are happy he is a doctor and not an artist!

Did you understand the drawing?, I didn’t… If you didn’t, don’t kill yourself over it, it is a pretty bad drawing. My partner did the drawing, so call him and let him know you are happy he is a doctor and not an artist!

If you understood it, you are a genius!… then skip the following sentence. If you did not understand it, then continue reading and do as you are told. Go to your anatomy book and do a little review. Now pretend you are the esophagus and try to imagine how all of your neighbors look from where you are.

If you understood it, you are a genius!… then skip the following sentence. If you did not understand it, then continue reading and do as you are told. Go to your anatomy book and do a little review. Now pretend you are the esophagus and try to imagine how all of your neighbors look from where you are.

All potential spaces in the chest and abdomen (pericardial, pleural, abdominal, sub-diaphragmatic, and hepato-renal) have the potential for fluid accumulation.

All potential spaces in the chest and abdomen (pericardial, pleural, abdominal, sub-diaphragmatic, and hepato-renal) have the potential for fluid accumulation.

Depending on the location, amount, and speed of accumulation, it can present as a clinically silent finding on TEE or it can cause hemodynamic compromise.

Depending on the location, amount, and speed of accumulation, it can present as a clinically silent finding on TEE or it can cause hemodynamic compromise.

Fluid is usually seen as black on echo, but if the fluid has solidified, as in the case of clotted blood, it can look just as the liver or lung atelectasis does!

Fluid is usually seen as black on echo, but if the fluid has solidified, as in the case of clotted blood, it can look just as the liver or lung atelectasis does!

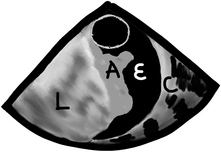

In a transgastric mid-short-axis view below, we can see lots of stuff besides the heart!

Gastric lining at the top, note the gastric rugae (those very tiny indentations in the very top of the echo image).

Gastric lining at the top, note the gastric rugae (those very tiny indentations in the very top of the echo image).

Pericardial reflection (that white line between “L” and the heart).

Pericardial reflection (that white line between “L” and the heart).

Moderate-sized focal image “C”, suggestive of clotted blood:

Moderate-sized focal image “C”, suggestive of clotted blood:

looks very similar to a layer of epicardial fat and can trick even the experts!

looks very similar to a layer of epicardial fat and can trick even the experts!

the history and additional findings will help define what the heck this is.

the history and additional findings will help define what the heck this is.

“Is there a pericardial effusion or not?” and if there is,

“Is there a pericardial effusion or not?” and if there is,

“Is there an aortic dissection?”

“Is there an aortic dissection?”

“Is there a clot in the pulmonary artery or other evidence of a pulmonary embolism?”

“Is there a clot in the pulmonary artery or other evidence of a pulmonary embolism?”

The Pericardium—we are back here again!

Is difficult to see by echo unless there is fluid on both sides of it or it is very thickened.

Is difficult to see by echo unless there is fluid on both sides of it or it is very thickened.

Can elicit some extra brightness on echo like it has its own light.

Can elicit some extra brightness on echo like it has its own light.

Has two layers (fibrous and serous).

Has two layers (fibrous and serous).

Serous layer has visceral and parietal aspects:

Serous layer has visceral and parietal aspects:

serous parietal layer is tightly bound to the fibrous pericardium that separates it from the rest of the chest structures

serous parietal layer is tightly bound to the fibrous pericardium that separates it from the rest of the chest structures

The layers extend a couple of centimeters, incorporating the aorta and main pulmonary artery.

The layers extend a couple of centimeters, incorporating the aorta and main pulmonary artery.

Confines the total volume the heart can handle at one time creating a closed volume relationship among all cardiac chambers.

Confines the total volume the heart can handle at one time creating a closed volume relationship among all cardiac chambers.

This limited volume relationship is the basis for the changes seen during effusions and restrictive or constrictive pericarditis.

This limited volume relationship is the basis for the changes seen during effusions and restrictive or constrictive pericarditis.

There is normally a bit of pericardial fluid or “oil” (normally 5 to 10 ml and rarely up to 50 ml) that lubricates the heart so it can dance without causing too much noise. Just like a car engine needs motor oil, so does the engine of the human body. Luckily, we don’t need oil changes every 3000 miles!

There is normally a bit of pericardial fluid or “oil” (normally 5 to 10 ml and rarely up to 50 ml) that lubricates the heart so it can dance without causing too much noise. Just like a car engine needs motor oil, so does the engine of the human body. Luckily, we don’t need oil changes every 3000 miles!

When the oil is too thick because the sac gets inflamed (pericarditis) or if the sac gets stiff, the pericardial layers rub as the heart moves and make some weird noises.

When the oil is too thick because the sac gets inflamed (pericarditis) or if the sac gets stiff, the pericardial layers rub as the heart moves and make some weird noises.

When the oil level is too high, we call this a pericardial effusion.

When the oil level is too high, we call this a pericardial effusion.

Several types of “oil” can fill the pericardial space:

Several types of “oil” can fill the pericardial space:

serum, sero-sanguineous fluid, blood, pus, solid things like metastatic tumors, fibrinous strands, etc.

serum, sero-sanguineous fluid, blood, pus, solid things like metastatic tumors, fibrinous strands, etc.

idiopathic causes, inflammation, infection, post heart attack, systemic conditions, malignancy, post trauma, surgery, radiation, congestive heart failure, etc.

idiopathic causes, inflammation, infection, post heart attack, systemic conditions, malignancy, post trauma, surgery, radiation, congestive heart failure, etc.

Pericardial effusion, like everything in medicine, we like to grade it, but there are no prizes, and the higher the grade AND speed of accumulation the worse!

Pericardial effusion, like everything in medicine, we like to grade it, but there are no prizes, and the higher the grade AND speed of accumulation the worse!

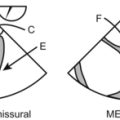

can be all around the heart (“E” in the image below) or just localized in an area (focal accumulation or loculated)

can be all around the heart (“E” in the image below) or just localized in an area (focal accumulation or loculated)

effusion can squeeze the whole heart or just a particular area

effusion can squeeze the whole heart or just a particular area

pericardial fluid or “effusion” can be:

pericardial fluid or “effusion” can be:

speed of fluid accumulation is a key factor to determine how fast the symptoms appear. Acutely an accumulation thicker than 1 cm could be considered significant, and usually causes tamponade

speed of fluid accumulation is a key factor to determine how fast the symptoms appear. Acutely an accumulation thicker than 1 cm could be considered significant, and usually causes tamponade

putting together the symptoms (hemodynamic compromise or not) and the echo findings, a diagnosis of tamponade or not can be made.

putting together the symptoms (hemodynamic compromise or not) and the echo findings, a diagnosis of tamponade or not can be made.

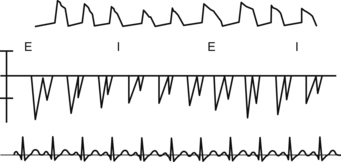

Pericardial-cardiac filling pressures are intimately related to breathing.

Pericardial-cardiac filling pressures are intimately related to breathing.

Normally during SPONTANEOUS inspiration there is a drop in intrathoracic and intrapericardial pressure. This facilitates right-sided filling, right ventricle stroke volume and a drop in blood flow out of the pulmonary veins, resulting in decreased left ventricular stroke volume.

Normally during SPONTANEOUS inspiration there is a drop in intrathoracic and intrapericardial pressure. This facilitates right-sided filling, right ventricle stroke volume and a drop in blood flow out of the pulmonary veins, resulting in decreased left ventricular stroke volume.

Normally during SPONTANEOUS expiration, intrathoracic and intrapericardial pressures increase causing a drop in right ventricular filling and stroke volume. This provides more space to the left ventricle and causes the squeezing of blood from the lungs into the left ventricle, resulting in an increased left ventricular stroke volume.

Normally during SPONTANEOUS expiration, intrathoracic and intrapericardial pressures increase causing a drop in right ventricular filling and stroke volume. This provides more space to the left ventricle and causes the squeezing of blood from the lungs into the left ventricle, resulting in an increased left ventricular stroke volume.

This cyclic variation in stroke volume during SPONTANEOUS breathing results in a less than 10 mmHg of inspiratory systolic systemic pressure drop during normal conditions.

This cyclic variation in stroke volume during SPONTANEOUS breathing results in a less than 10 mmHg of inspiratory systolic systemic pressure drop during normal conditions.

If this systolic blood pressure variation exceeds 10 mmHg it is called “pulsus paradoxus”. During conditions that increase respiratory effort (COPD, acute asthma, etc.), hypovolemia, or tamponade this pressure variation is greatly exaggerated.

If this systolic blood pressure variation exceeds 10 mmHg it is called “pulsus paradoxus”. During conditions that increase respiratory effort (COPD, acute asthma, etc.), hypovolemia, or tamponade this pressure variation is greatly exaggerated.

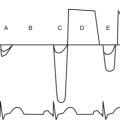

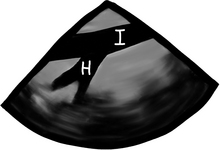

During MECHANICAL ventilation, the intrathoracic pump-sucking effect created by the negative pressure during SPONTANEOUS inspiration is lost and things get much worse for the blood pressure if there is tamponade. During MECHANICAL ventilation, the ventilation-pericardial pressure/cardiac filling relationship is reversed and the inspiratory thoracic pump is GONE! All this stuff is easily seen if the patient has an arterial line (top tracing) and also if left ventricular filling patterns are measured using PWD (middle tracing) through the mitral valve. “I” = inspiration; “E” = expiration.

During MECHANICAL ventilation, the intrathoracic pump-sucking effect created by the negative pressure during SPONTANEOUS inspiration is lost and things get much worse for the blood pressure if there is tamponade. During MECHANICAL ventilation, the ventilation-pericardial pressure/cardiac filling relationship is reversed and the inspiratory thoracic pump is GONE! All this stuff is easily seen if the patient has an arterial line (top tracing) and also if left ventricular filling patterns are measured using PWD (middle tracing) through the mitral valve. “I” = inspiration; “E” = expiration.

Normally the respiratory variation for tricuspid inflow velocity (this is proportional to ventricular filling) is less than 25% and for mitral less than 15%. This is all very scientific, but it is better just to do simple math: symptoms + 2D echo finding = diagnosis.

Normally the respiratory variation for tricuspid inflow velocity (this is proportional to ventricular filling) is less than 25% and for mitral less than 15%. This is all very scientific, but it is better just to do simple math: symptoms + 2D echo finding = diagnosis.

Cardiac chamber collapse during diastole is diagnostic of tamponade. Usually tamponade is a clinical diagnosis with imaging support, but sometimes chamber collapse can be seen before symptoms are clearly seen. If a patient had a thick right ventricle, collapse may be absent, despite having tamponade.

Cardiac chamber collapse during diastole is diagnostic of tamponade. Usually tamponade is a clinical diagnosis with imaging support, but sometimes chamber collapse can be seen before symptoms are clearly seen. If a patient had a thick right ventricle, collapse may be absent, despite having tamponade.

If the pericardial sac gets stiff, due to inflammation, tissue infiltration, or calcification, then it can affect the heart motion and filling causing restrictive and/or constrictive pericarditis. It is very hard to “see” pericardial sac thickening, stiffness, or calcification by echo and most of the time we just see the effect of the stiffness on the heart.

If the pericardial sac gets stiff, due to inflammation, tissue infiltration, or calcification, then it can affect the heart motion and filling causing restrictive and/or constrictive pericarditis. It is very hard to “see” pericardial sac thickening, stiffness, or calcification by echo and most of the time we just see the effect of the stiffness on the heart.

CT and MRI are better diagnostic tools for pericardial layer imaging, especially if there is no associated effusion.

CT and MRI are better diagnostic tools for pericardial layer imaging, especially if there is no associated effusion.

The Aorta

Is the strongest tube we have, and one of the longest.

Is the strongest tube we have, and one of the longest.

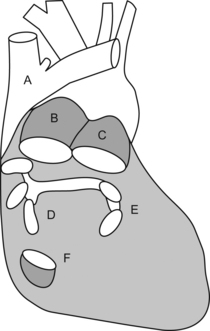

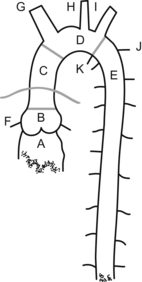

Has six segments starting at the aortic valve annulus (annulus located between “A” and “B” in the aortic figure), with a diameter of about 3 cm, the sinus of Valsalva (at “B”), sinotubular junction (area connecting segments “B” and “C”), ascending aorta (“B”+“C”, 5 cm long), arch (segment “D”, from origin of innominate artery to end of left subclavian artery), and descending aorta (segment “E”, starting after left subclavian, and “K” ligamentum arteriosum and continuing to the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta).

Has six segments starting at the aortic valve annulus (annulus located between “A” and “B” in the aortic figure), with a diameter of about 3 cm, the sinus of Valsalva (at “B”), sinotubular junction (area connecting segments “B” and “C”), ascending aorta (“B”+“C”, 5 cm long), arch (segment “D”, from origin of innominate artery to end of left subclavian artery), and descending aorta (segment “E”, starting after left subclavian, and “K” ligamentum arteriosum and continuing to the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta).

The “aortic root” includes the aortic annulus up to the proximal ascending aorta, and is included in the pericardial sac.

The “aortic root” includes the aortic annulus up to the proximal ascending aorta, and is included in the pericardial sac.

The ascending is contained, with the pulmonary artery trunk, in the pericardial sac and can be divided into the root with its sinus of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, and ascending aorta.

The ascending is contained, with the pulmonary artery trunk, in the pericardial sac and can be divided into the root with its sinus of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, and ascending aorta.

The aorta ends at the level of the 4th lumbar vertebra with about 1.75 cm in diameter as it bifurcates into the common iliac arteries.

The aorta ends at the level of the 4th lumbar vertebra with about 1.75 cm in diameter as it bifurcates into the common iliac arteries.

The coronary arteries are the only branches of the ascending aorta.

The coronary arteries are the only branches of the ascending aorta.

The arch gives origin to the innominate artery, left carotid and left subclavian, although there are many anatomical variations that these vessels can have.

The arch gives origin to the innominate artery, left carotid and left subclavian, although there are many anatomical variations that these vessels can have.

The descending aorta gives origin to intercostals and some abdominal branches that often can be seen by TEE, like the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and sometimes even the renal arteries.

The descending aorta gives origin to intercostals and some abdominal branches that often can be seen by TEE, like the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and sometimes even the renal arteries.

The descending thoracic aorta in long-axis view looks like an evenly sized black tube and it should have a smooth inner surface:

The descending thoracic aorta in long-axis view looks like an evenly sized black tube and it should have a smooth inner surface:

the area at your left in the image below is distal and to your right is proximal aorta

the area at your left in the image below is distal and to your right is proximal aorta

distal in the screen we see again lung or just chest wall and ribs depending on the esophageal to aorta alignment.

distal in the screen we see again lung or just chest wall and ribs depending on the esophageal to aorta alignment.

CT and MRI provide excellent views of the aorta, its branches, and of all extra cardiac structures, but they require IV contrast. Additionally, the MRI/MRA requires lots of time. CT and MRI are also both very “difficult” to do in the operating room!

CT and MRI provide excellent views of the aorta, its branches, and of all extra cardiac structures, but they require IV contrast. Additionally, the MRI/MRA requires lots of time. CT and MRI are also both very “difficult” to do in the operating room!

TEE can give a quick assessment of almost the entire aorta, from origin to upper/mid abdomen. It is best to start your exam at the aortic valve annulus and to try to follow the aorta all the way to the belly.

TEE can give a quick assessment of almost the entire aorta, from origin to upper/mid abdomen. It is best to start your exam at the aortic valve annulus and to try to follow the aorta all the way to the belly.

It is best to examine the aorta in a short-axis view. This will prevent you from missing something. Once an area of concern is identified then a long-axis exam can add valuable information, such as length of the pathology, which can help reconstruct a 3-D mental view of the problem. We can actually do real-time 3-D views as well with some machines.

It is best to examine the aorta in a short-axis view. This will prevent you from missing something. Once an area of concern is identified then a long-axis exam can add valuable information, such as length of the pathology, which can help reconstruct a 3-D mental view of the problem. We can actually do real-time 3-D views as well with some machines.

We are not going to give you the TEE multiplane angles “recommended”. Instead you should try to:

We are not going to give you the TEE multiplane angles “recommended”. Instead you should try to:

follow the aorta as you move from the aortic root to the ascending

follow the aorta as you move from the aortic root to the ascending

once you lose the ascending aorta view, due to tracheal interposition between the aorta and esophagus, turn the TEE probe to the patient’s left (if you are standing at the head of the bed) to find the proximal descending aorta

once you lose the ascending aorta view, due to tracheal interposition between the aorta and esophagus, turn the TEE probe to the patient’s left (if you are standing at the head of the bed) to find the proximal descending aorta

once you find the descending aorta, by pulling/withdrawing the TEE probe you reach the aortic arch

once you find the descending aorta, by pulling/withdrawing the TEE probe you reach the aortic arch

after you have given a good look at the arch, try to find the arch vessels, especially the left subclavian which is easily seen in the distal arch. Make sure you do not pull the probe out of the patient while looking at arch branches—we have done that!

after you have given a good look at the arch, try to find the arch vessels, especially the left subclavian which is easily seen in the distal arch. Make sure you do not pull the probe out of the patient while looking at arch branches—we have done that!

then, while reinserting the probe, try to follow the aorta down to its most distal aspect in the abdomen

then, while reinserting the probe, try to follow the aorta down to its most distal aspect in the abdomen

sometimes the aorta can be tortuous and you must “follow” it by turning the probe

sometimes the aorta can be tortuous and you must “follow” it by turning the probe

other times the aorta just disappears when you are following it distally—it’s OK—these are just segments of the aorta that have a poor echo window. In this situation, just prevent the probe from turning left or right and continue to advance distally until the aorta reappears

other times the aorta just disappears when you are following it distally—it’s OK—these are just segments of the aorta that have a poor echo window. In this situation, just prevent the probe from turning left or right and continue to advance distally until the aorta reappears

Aortic aneurysm, dissection, and atheroma are the 3 big things. The good thing is that we know what these things look like in the anatomic specimen. With TEE it is only black-and-white images.

Aortic Aneurysm

An aneurysm is a dilation greater than 1.5 times the normal size for that structure.

An aneurysm is a dilation greater than 1.5 times the normal size for that structure.

The ascending aorta is much larger than the aortic root and sinotubular junction in the image below…what could this be? Yes, you are correct an aneurysm it is!

The ascending aorta is much larger than the aortic root and sinotubular junction in the image below…what could this be? Yes, you are correct an aneurysm it is!

Sometimes we don’t know what the normal size is, but comparing to other areas of the same structure usually gives us a hint that things are bigger than they should be!

Sometimes we don’t know what the normal size is, but comparing to other areas of the same structure usually gives us a hint that things are bigger than they should be!

Aneurysms can be isolated or associated with a cardiovascular problem like HTN, aortic valve disease (AS/AI/bicuspid aortic valve), Marfan’s, etc.

Aneurysms can be isolated or associated with a cardiovascular problem like HTN, aortic valve disease (AS/AI/bicuspid aortic valve), Marfan’s, etc.

Ascending aortic dilation can cause secondary aortic valve insufficiency as well.

Ascending aortic dilation can cause secondary aortic valve insufficiency as well.

Aneurysms greater than 5 cm or a rapidly growing (>5 mm/year) are often used as indications for surgery. These are most commonly CT- or MRA-based diagnosis.

Aneurysms greater than 5 cm or a rapidly growing (>5 mm/year) are often used as indications for surgery. These are most commonly CT- or MRA-based diagnosis.

Patients with Marfan’s or other connective tissue disorders usually have other cardiovascular anomalies. Thus a complete exam must be done.

Patients with Marfan’s or other connective tissue disorders usually have other cardiovascular anomalies. Thus a complete exam must be done.

Aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva, like in any other portion of the aorta, can also occur. Depending on which sinus is affected, it can rupture into the right atrium (most commonly) or distort the annulus and cause aortic valve insufficiency.

Aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva, like in any other portion of the aorta, can also occur. Depending on which sinus is affected, it can rupture into the right atrium (most commonly) or distort the annulus and cause aortic valve insufficiency.

Aortic Pseudoaneurysm

Aortic pseudoaneurysm is a contained rupture of the aorta where the aneurysm wall is made of non aortic tissues (surrounding tissues).

Aortic pseudoaneurysm is a contained rupture of the aorta where the aneurysm wall is made of non aortic tissues (surrounding tissues).

Usually has a narrow neck, like in the case of a ventricular pseudoaneurysm.

Usually has a narrow neck, like in the case of a ventricular pseudoaneurysm.

Can be spontaneous, secondary to an aneurysm, trauma, post surgery, iatrogenic, or infection.

Can be spontaneous, secondary to an aneurysm, trauma, post surgery, iatrogenic, or infection.

Aortic Dissection

Dissection occurs when a breach in the intima allows pressurized blood to separate the intima from the medial layers. In the image below note the double wall in the ascending aorta, typical of dissection.

Dissection occurs when a breach in the intima allows pressurized blood to separate the intima from the medial layers. In the image below note the double wall in the ascending aorta, typical of dissection.

Blood can propagate proximally, distally, or both between the intima and medial layers.

Blood can propagate proximally, distally, or both between the intima and medial layers.

Can present as a clearly separated layer with a flow-like pattern, often with several entry/exit points connecting the “true” and “false” lumens (so called “fenestrations”).

Can present as a clearly separated layer with a flow-like pattern, often with several entry/exit points connecting the “true” and “false” lumens (so called “fenestrations”).

Sometimes it is difficult to find the “true” lumen, and color flow Doppler can help in finding these fenestrations and define which one is the perfusing lumen and which is not.

Sometimes it is difficult to find the “true” lumen, and color flow Doppler can help in finding these fenestrations and define which one is the perfusing lumen and which is not.

The “true” lumen usually expands with systole and has a regular shape (from circular to a flat tube).

The “true” lumen usually expands with systole and has a regular shape (from circular to a flat tube).

Dissections can also present as an intramural hematoma (5–10%) and they must be differentiated from a smooth-layered atheroma. Intimal layered calcifications (in the wall, below the plaque) and close observation of the surface usually help distinguish the plaque from intramural hematoma, where calcifications, if present, are in the intimal layer of the hematoma.

Dissections can also present as an intramural hematoma (5–10%) and they must be differentiated from a smooth-layered atheroma. Intimal layered calcifications (in the wall, below the plaque) and close observation of the surface usually help distinguish the plaque from intramural hematoma, where calcifications, if present, are in the intimal layer of the hematoma.

Dissection can be localized or diffuse, and occasionally it can present as an intimal tear without dissection.

Dissection can be localized or diffuse, and occasionally it can present as an intimal tear without dissection.

Another way dissections can occur is of iatrogenic origin (cardiac catheterization, post aortic cannulation, etc.), or when an ulcerated atherosclerotic plaque suffers penetration into the intimal/medial layer.

Another way dissections can occur is of iatrogenic origin (cardiac catheterization, post aortic cannulation, etc.), or when an ulcerated atherosclerotic plaque suffers penetration into the intimal/medial layer.

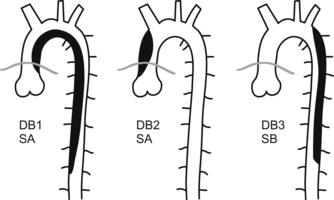

Dissections are classified as Stanford A or B (SA or SB) or DeBakey I, II, or III (DB1, DB2, or DB3) types.

Dissections are classified as Stanford A or B (SA or SB) or DeBakey I, II, or III (DB1, DB2, or DB3) types.

all dissections involving the ascending aorta or arch are considered life-threatening emergencies and must be taken to the operating room as soon as possible. These can rupture or extend and cause tamponade, aortic insufficiency, myocardial or cerebral ischemia or infarct, or exsanguination

all dissections involving the ascending aorta or arch are considered life-threatening emergencies and must be taken to the operating room as soon as possible. These can rupture or extend and cause tamponade, aortic insufficiency, myocardial or cerebral ischemia or infarct, or exsanguination

dissections occurring distal to the left subclavian artery are managed medically unless there are signs of organ or limb malperfusion. In this case, they can be managed by endovascular techniques or operatively to restore compromised blood flow.

dissections occurring distal to the left subclavian artery are managed medically unless there are signs of organ or limb malperfusion. In this case, they can be managed by endovascular techniques or operatively to restore compromised blood flow.

Surgery of an aneurysm or a dissection:

Surgery of an aneurysm or a dissection:

intends to prevent propagation of the dissection, its complications, or rupture

intends to prevent propagation of the dissection, its complications, or rupture

after repair of an ascending aortic aneurysm or dissection, myocardial and aortic valve function must be assessed to make sure coronary blood flow was not compromised and there is no significant valve dysfunction

after repair of an ascending aortic aneurysm or dissection, myocardial and aortic valve function must be assessed to make sure coronary blood flow was not compromised and there is no significant valve dysfunction

if the dissection extended distally originally the distal false lumen will persist after surgery, sometimes with flow in it. Chronic thrombosis often occurs.

if the dissection extended distally originally the distal false lumen will persist after surgery, sometimes with flow in it. Chronic thrombosis often occurs.

Aortic Plaque

Aortic plaque or atherosclerosis is a common finding in our older or vascular patients.

Hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, and poor diet (usually a Western diet; i.e. most of us!!!! I’ll take a Big Mac and fries please. Oh and can you supersize that! STAT!) are all risk factors.

Hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, and poor diet (usually a Western diet; i.e. most of us!!!! I’ll take a Big Mac and fries please. Oh and can you supersize that! STAT!) are all risk factors.

Plaque is often located in the arch and descending aorta, and is less common in the ascending aorta.

Plaque is often located in the arch and descending aorta, and is less common in the ascending aorta.

The most common site for plaque in the ascending is the right sinotubular junction area and if calcified will give a nice black shadow (see image below), as the ultrasound is pretty bad at penetrating through calcium. As a result of the echo “shadow”, we are not able to see beyond the calcification. If we want to see what “lies beneath”, we will need to find this through alternative imaging angles.

The most common site for plaque in the ascending is the right sinotubular junction area and if calcified will give a nice black shadow (see image below), as the ultrasound is pretty bad at penetrating through calcium. As a result of the echo “shadow”, we are not able to see beyond the calcification. If we want to see what “lies beneath”, we will need to find this through alternative imaging angles.

Atheromas can take almost any shape and size, sometimes artistic, mostly very scary! They can be flat, round, mountain looking, pedunculated, mobile or not, as well as calcified or not.

Atheromas can take almost any shape and size, sometimes artistic, mostly very scary! They can be flat, round, mountain looking, pedunculated, mobile or not, as well as calcified or not.

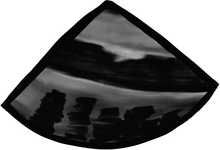

In this long-axis view of the descending thoracic aorta a large atherosclerotic plaque can be seen, yes! that white blob attached to the inner surface of the aorta.

In this long-axis view of the descending thoracic aorta a large atherosclerotic plaque can be seen, yes! that white blob attached to the inner surface of the aorta.

The bigger and more mobile they are, the higher risk for stroke and embolic phenomena there is.

The bigger and more mobile they are, the higher risk for stroke and embolic phenomena there is.

We should define these plaques by their location, size (measure from base to highest point), and if mobile or not.

We should define these plaques by their location, size (measure from base to highest point), and if mobile or not.

Aneurysm, dissection, and plaque can overlap in the same patient making its management more complicated.

Aneurysm, dissection, and plaque can overlap in the same patient making its management more complicated.

Aortic Trauma

Most commonly occurs after blunt chest trauma, usually due to high-speed impact.

Most commonly occurs after blunt chest trauma, usually due to high-speed impact.

The aorta has several areas where it is relatively fixed (annulus to heart, neck vessels, descending thoracic aorta fixed by intercostals) to the chest and other areas where it is mobile (ascending and arch).

The aorta has several areas where it is relatively fixed (annulus to heart, neck vessels, descending thoracic aorta fixed by intercostals) to the chest and other areas where it is mobile (ascending and arch).

The aorta can rotate and twist at the aortic root, can bend at the arch vessel area, and at the ligamentum arteriosum area.

The aorta can rotate and twist at the aortic root, can bend at the arch vessel area, and at the ligamentum arteriosum area.

The aorta most commonly breaks at the root, arch vessel area, or at its fixture at the ligamentum arteriosum area.

The aorta most commonly breaks at the root, arch vessel area, or at its fixture at the ligamentum arteriosum area.

If the transection is complete, kaput you are DEAD!

If the transection is complete, kaput you are DEAD!

Partial transections are what we see, and CT is the primary diagnostic mode because it is part of the usual trauma workup.

Partial transections are what we see, and CT is the primary diagnostic mode because it is part of the usual trauma workup.

TEE can miss small tears in the arch and ligamentum area as they are difficult to see with TEE due to tracheal interposition. Anyway aortic shape disruption, adventitial hematoma, small evagination of the wall, intraluminal hematoma, small flaps or tears can be seen.

TEE can miss small tears in the arch and ligamentum area as they are difficult to see with TEE due to tracheal interposition. Anyway aortic shape disruption, adventitial hematoma, small evagination of the wall, intraluminal hematoma, small flaps or tears can be seen.

If you don’t see anything by TEE, but there is strong suspicion of a transection, then a CTA or angiogram (much less used these days) must be done.

If you don’t see anything by TEE, but there is strong suspicion of a transection, then a CTA or angiogram (much less used these days) must be done.

Aortic trauma can also be present with rupture of any other cardiac structures: sinus of Valsalva into the right atrium, traumatic atrial-septal defect, rupture of a papillary muscle (tricuspid or mitral), aorto-caval fistula, etc.

Aortic trauma can also be present with rupture of any other cardiac structures: sinus of Valsalva into the right atrium, traumatic atrial-septal defect, rupture of a papillary muscle (tricuspid or mitral), aorto-caval fistula, etc.

Pulmonary Artery

It can tell us a bit about the chronic pulmonary vasculature strain it suffers with chronic severe mitral regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension (primary or secondary to asthma, COPD, etc.), acute or chronic pulmonary embolism, etc. In all chronic cases it gets BIG, and we don’t mean fat, but dilated like a nice round Italian sausage.

It can tell us a bit about the chronic pulmonary vasculature strain it suffers with chronic severe mitral regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension (primary or secondary to asthma, COPD, etc.), acute or chronic pulmonary embolism, etc. In all chronic cases it gets BIG, and we don’t mean fat, but dilated like a nice round Italian sausage.

Did you know that a pulmonary embolism is one of the most common causes of sudden unexpected intraoperative cardiac arrest?!? But of course you knew! The other common causes include acute myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, tamponade, and severe hypovolemia. ALL, but arrhythmias can have its diagnosis “assisted” by TEE.

Did you know that a pulmonary embolism is one of the most common causes of sudden unexpected intraoperative cardiac arrest?!? But of course you knew! The other common causes include acute myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, tamponade, and severe hypovolemia. ALL, but arrhythmias can have its diagnosis “assisted” by TEE.

As a rule made by us, the right (“R”) and left (“L”) pulmonary artery should be 2/3 the diameter of the main pulmonary artery (“P”), and the main PA and SVC (“S” = short-axis superior vena cava) should be 2/3 of the ascending aorta (“A” = short-axis ascending aorta). This “2/3” rule also applies to many other chambers and tubes in the heart.

As a rule made by us, the right (“R”) and left (“L”) pulmonary artery should be 2/3 the diameter of the main pulmonary artery (“P”), and the main PA and SVC (“S” = short-axis superior vena cava) should be 2/3 of the ascending aorta (“A” = short-axis ascending aorta). This “2/3” rule also applies to many other chambers and tubes in the heart.

In the image below, take note that the main PA has a similar diameter to the ascending aorta, probably because there is some chronic abnormality occurring with the PA.

In the image below, take note that the main PA has a similar diameter to the ascending aorta, probably because there is some chronic abnormality occurring with the PA.

Sometimes we get lucky and can see an embolus occluding the main or proximal PA branches, but most of the time we just see signs of right ventricular strain. In cases of pulmonary embolism, signs include PA dilation, RV dysfunction, RV dilation (“R”), tricuspid insufficiency, dilated RA, bulging of the interatrial septum to the left, and flattening of the interventricular septum (the so-called “D”-shaped left ventricle (“L”) or a really squashed LV!).

Sometimes we get lucky and can see an embolus occluding the main or proximal PA branches, but most of the time we just see signs of right ventricular strain. In cases of pulmonary embolism, signs include PA dilation, RV dysfunction, RV dilation (“R”), tricuspid insufficiency, dilated RA, bulging of the interatrial septum to the left, and flattening of the interventricular septum (the so-called “D”-shaped left ventricle (“L”) or a really squashed LV!).

Now what? We looked at the tubes going out of the heart. Now it’s time for the incoming pipes.

Superior Vena Cava, Inferior Vena Cava, and their Cousins the Hepatic Veins

In this modified bicaval view, we can see the left atrium (“L”), the interatrial septum and its thinner/thinner area (the fossa ovalis), the right atrium (“R”), the SVC (“S”), the IVC (“I”), the entrance of the coronary sinus (“C”), and the right atrial appendage with its typical broad base (“A”). The tricuspid valve (“T”) can also be partially seen, as well as some of the right ventricle (“RV”).

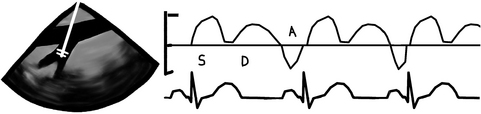

Like the pulmonary venous flow, has 3 main waves, the “S”, “D”, and “A” waves.

Like the pulmonary venous flow, has 3 main waves, the “S”, “D”, and “A” waves.

Place the pulsed wave Doppler cursor, also called the “gate” or “sampling volume”, 1 cm into the hepatic vein. Then we press the PWD button and voila, a waveform for the hepatic venous flow is displayed:

Place the pulsed wave Doppler cursor, also called the “gate” or “sampling volume”, 1 cm into the hepatic vein. Then we press the PWD button and voila, a waveform for the hepatic venous flow is displayed:

“S” wave corresponds to ventricular systole. During this time, the area of the heart with the closed tricuspid and mitral valves (aka the base of the heart; I’d like to ask a few questions to the person who named this!) is pulled down and a suction effect facilitates forward flow to the atria

“S” wave corresponds to ventricular systole. During this time, the area of the heart with the closed tricuspid and mitral valves (aka the base of the heart; I’d like to ask a few questions to the person who named this!) is pulled down and a suction effect facilitates forward flow to the atria

Next the valves open and the “D” wave (diastolic) occurs as the atrial blood volume emptying into the ventricles makes room for more blood to move into the atria

Next the valves open and the “D” wave (diastolic) occurs as the atrial blood volume emptying into the ventricles makes room for more blood to move into the atria

Finally, when atrial contraction occurs the “A” wave (atrial) is generated because most of the blood is pumped into the ventricles, but some is pumped retrograde into the hepatic or pulmonary veins. This causes the “A” wave to inscribe below the baseline. Yes, you figured it out! This is the so-called atrial flow reversal and it is totally normal.

Finally, when atrial contraction occurs the “A” wave (atrial) is generated because most of the blood is pumped into the ventricles, but some is pumped retrograde into the hepatic or pulmonary veins. This causes the “A” wave to inscribe below the baseline. Yes, you figured it out! This is the so-called atrial flow reversal and it is totally normal.

In cases of severe tricuspid or mitral regurgitation, because the valve is incompetent, blood flow is pumped into the atrium during ventricular systole and from there into the hepatic or pulmonary veins. The normal forward flow of the “S” wave is seen as totally blunted or even reversed and inscribed below the baseline. This tells us that blood is going into the hepatic or pulmonary vein in ventricular systole instead of coming out of them and into the atria. It’s pretty neat that we are able to follow blood flow in real time without having to cut the heart open!

In cases of severe tricuspid or mitral regurgitation, because the valve is incompetent, blood flow is pumped into the atrium during ventricular systole and from there into the hepatic or pulmonary veins. The normal forward flow of the “S” wave is seen as totally blunted or even reversed and inscribed below the baseline. This tells us that blood is going into the hepatic or pulmonary vein in ventricular systole instead of coming out of them and into the atria. It’s pretty neat that we are able to follow blood flow in real time without having to cut the heart open!

Well, well we are not done, but from here on it is much easier!

The azygos vein, trachea, thymus (in children), and spine can be seen, but add very little in acute care.

The azygos vein, trachea, thymus (in children), and spine can be seen, but add very little in acute care.

For fun we can see the stomach and its contents thus having an idea if there is some significant gastric content.

For fun we can see the stomach and its contents thus having an idea if there is some significant gastric content.

From the gastric window, the liver and spleen are easily identified.

From the gastric window, the liver and spleen are easily identified.

Within the liver, the inferior vena cava has a normal diameter change with respiration, suggestive of normal CVP.

Within the liver, the inferior vena cava has a normal diameter change with respiration, suggestive of normal CVP.

if there is a lack of IVC diameter change or the IVC is dilated this is suggestive of elevated CVP. This is an easy way to have an idea about what is going on with the right heart.

if there is a lack of IVC diameter change or the IVC is dilated this is suggestive of elevated CVP. This is an easy way to have an idea about what is going on with the right heart.

The right kidney and the hepato-renal space (Morrison pouch), as well as the subdiaphragmatic area, will show any fluid accumulation in the right upper quadrant.

The right kidney and the hepato-renal space (Morrison pouch), as well as the subdiaphragmatic area, will show any fluid accumulation in the right upper quadrant.

We leave the lung and pleural space for last.

We leave the lung and pleural space for last.

TEE exam is never complete if we do not look at the left and right pleural spaces

TEE exam is never complete if we do not look at the left and right pleural spaces

lung can be seen with its typical aerated pattern

lung can be seen with its typical aerated pattern

if there is lung atelectasis or condensation it looks like liver. Remember?

if there is lung atelectasis or condensation it looks like liver. Remember?

pneumothorax is much more difficult to diagnose and we will leave that for you to research!

pneumothorax is much more difficult to diagnose and we will leave that for you to research!

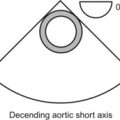

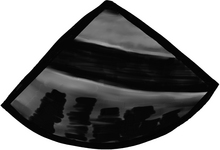

pleural effusions are easy to see, but we need to look for them. The best view to start looking for pleural effusions is in the descending aorta short-axis view. Anything we see in this location, we will know belongs to the left chest, as seen in the following image. This is a short-axis view of the descending aorta with normal lung (“L”), atelectatic lung which looks very similar to the liver in echo (“A”), pleural effusion (“E”), and the chest wall with the ribs and all (“C”).

pleural effusions are easy to see, but we need to look for them. The best view to start looking for pleural effusions is in the descending aorta short-axis view. Anything we see in this location, we will know belongs to the left chest, as seen in the following image. This is a short-axis view of the descending aorta with normal lung (“L”), atelectatic lung which looks very similar to the liver in echo (“A”), pleural effusion (“E”), and the chest wall with the ribs and all (“C”).

After we are done with the left chest we have two options, you can just rotate to the right at the level of the atria until you find a right effusion or normal lung. You could also simply find the liver and pull the probe straight back from there until you see the right lung. Be careful not to pull out so much or the TEE probe will come out of the patient’s mouth!

After we are done with the left chest we have two options, you can just rotate to the right at the level of the atria until you find a right effusion or normal lung. You could also simply find the liver and pull the probe straight back from there until you see the right lung. Be careful not to pull out so much or the TEE probe will come out of the patient’s mouth!